Duchy of Württemberg

The Duchy of Württemberg (German: Herzogtum Württemberg) was a duchy located in the south-western part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a member of the Holy Roman Empire from 1495 to 1806. The dukedom's long survival for over three centuries was mainly due to its size, being larger than its immediate neighbors. During the Protestant Reformation, Württemberg faced great pressure from the Holy Roman Empire to remain a member. Württemberg resisted repeated French invasions in the 17th and 18th centuries. Württemberg was directly in the path of French and Austrian armies who were engaged in the long rivalry between the House of Bourbon and the House of Habsburg. In 1803, Napoleon raised the duchy to be the Electorate of Württemberg of the Holy Roman Empire. On 1 January 1806, the last Elector assumed the title of King of Württemberg. Later that year, on 6 August 1806, the last Emperor, Francis II, abolished (de facto) the Holy Roman Empire.

Duchy of Württemberg Herzogtum Württemberg | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1495–1803 | |||||||||

Flag

| |||||||||

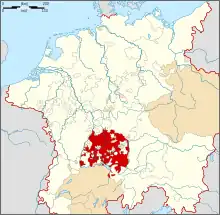

.svg.png.webp) Duchy of Württemberg within the Holy Roman Empire (1618) | |||||||||

| Capital | Stuttgart | ||||||||

| Common languages | Swabian German | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic Lutheran | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Württemberger | ||||||||

| Government | Duchy | ||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||

• 1495–1496 | Eberhard I (first) | ||||||||

• 1797–1803 | Frederick II (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern Napoleonic | ||||||||

| 21 July 1495 | |||||||||

| May 1514 | |||||||||

• Raised to Electorate | 1803 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany France | ||||||||

Geography

Much of the territory of the Duchy of Württemberg lies in the valley of the Neckar river, from Tübingen to Heilbronn, with its capital and largest city, Stuttgart, in the center. The northern part of Württemberg is wide and open, with large rivers making for decent arable land. The southern part of Württemberg is mountainous and wooded, with the Black Forest to the west and the Swabian Alb to the east. The very southeastern part of the Duchy, on the other side of the Swabian Alb, is the Danube river basin. The Duchy of Württemberg was over 8,000 square kilometres (3,100 sq mi) of pastures, forests, and rivers. Politically, it was a patchwork of 350 smaller territories governed by many different secular and ecclesiastical landlords. As early as the 14th century, it had dissolved into many districts (called Ämter or Vogteien in German), which originally were called "Steuergemeinde," a "small, taxable community." By 1520, the number of these districts had risen to 45, from 38 in 1442, and would number 58 by the end of the 16th century. These varied vastly in size, with Urach containing 76 outlying villages to Ebingen, which only contained its eponymous town.[1]

Württemberg was also one of the most populous regions of the Holy Roman Empire, supporting 300,000-400,000 inhabitants (and a birthrate that grew 6–7% each year) in the 16th century, 70% of which lived in the countryside. The largest town in the Duchy was Stuttgart (9,000), followed by Tübingen, then Schorndorf, and Kirchheim-Teck (2,000-5,000), and over 670 villages that contained the rest of the population.[2]

History

Foundation

The Duchy of Württemberg was formed when, at the Diet of Worms, 21 July 1495, Maximilian I, King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor, declared the Count of Württemberg (German: Graf von Württemberg), Eberhard V "the Bearded," Duke of Württemberg (German: Herzog von Württemberg).[3] This would be the last elevation to Dukedom of the Medieval era.[4] The House of Württemberg had reigned over the territory since the 11th century, and Duke Eberhard I himself ascended to the throne in 1450[5] at the age of 14,[6] over a territory split in two states: the Württemberg ruled by the Württemberg-Stuttgart line, and the Württemberg of the Württemberg-Urach line. In 1482, he united the two parts of the future Duchy,[7] fusing the governments of both counties into what would be the basis of the Duchy's central government.[5]

After Eberhard's death in 1496, he was succeeded by his cousin, Eberhard II, and he would make little change to the government's structure. Despite having earlier been the Count from 1480 to 1482, he proved to be administratively incompetent, and his attempt to begin a war against Bavaria prompted the Estates to request Maximilian I to call a diet in March 1498 to remove Eberhard II. The Emperor then made the unprecedented decision to side with the Estates and thus deprived Duke Eberhard II of his principality in May 1498. While the Duke's advisers were arrested or fled, Eberhard II himself was banished to Lindenfels Castle and granted an annuity of 6000 florins until his death in 1504. The one accomplishment of Eberhard II's reign was the establishment of the Hofkapelle for the performance of religious music, and this system of music patronage would remain uninterrupted until the Thirty Years' War.[8]

Duke Ulrich's first reign

Ulrich, of the Urach line of the Württemberg family,[7] succeeded Eberhard II in 1498, in his minority. His regency was controlled by four nobles: Counts Wolfgang von Fürstenberg and Andreas von Waldburg, Hans von Reischach (the senior bailiff of Mömpelgard), and Diepolt Spät (the senior bailiff of Tübingen).[lower-alpha 1] Two other men, the abbots of Zwiefalten and Bebenhausen, also held advisory positions in the regency. While the regency would hear the wishes of the people through the Estates, they became opposed to the wishes of the local burghers during the very unpopular Swabian War, to which the Estates voted more soldiers and money.[6]

Maximilian I declared Ulrich I of age at 16, in the process violating the 1492 Treaty of Esslingen that stipulated that he could only fully succeed at 20.[9] Thus began one of the longest and most tumultuous periods in the history of the region. The young Duke at first made little change to the government, allowing his councilors to decide on policy while he made his greatest marks in the Duchy through the expansion of the realm, usually through war. With the aid of Duke Albert IV of Bavaria and Maximilian I, Ulrich invaded the Rhine Palatinate with an army of 20,000 soldiers, obtaining Maulbronn Abbey, the County of Löwenstein and the districts of Weinsberg, Neuenstadt am Kocher, and Möckmühl from the Palatinate as well as Heidenheim an der Brenz and the abbeys of Königsbronn, Anhausen, and Herbrechtingen. Ulrich's ability to rule, on the other hand, was less reliable. The first crisis he faced was financial: since the beginning of his reign to 1514, he had racked up a debt of more than 600,000 florins in addition to the debt of 300,000 florins he inherited, amounting to almost one million florins. Ulrich attempted to assuage this with a 6% wealth tax (1 pfennig on 1 gulden), which was met with fierce resistance by his subjects, particularly the Ehrbarkeit, who had the most to lose. Ulrich refused to call a diet to discuss this tax, but he did not press it and repealed it. Following this failure, Ulrich next tried an indirect tax (3 schilling heller on the Centner) on consumables such as meats, wine and grain. Again Ulrich refused to call a diet to discuss the tax, but successfully levied it through local and district officials. This particular tax was intensely unpopular, even more so than the first, as it was implemented by the officials who had dodged the first tax, drove the prices of their food up and,[10] to the chagrin of the lower classes, Ulrich and his government sought to have Roman law officially accepted into Württemberg's legal system.[11]

The tax, combined with the statute passed by the Estates in 1514 that denied scales and weights, further hurting merchants and farmers, the lack of say commoners had in their own government, and the restriction of the use of the forests, rivers and meadows around them caused much unrest. To pour salt into the wound, the commoners came to dread the increase in lawyers and officials, who brought new legal methods.[lower-alpha 2] A list of grievances from the peasantry makes clear their dissatisfaction,[13] and the final result of this dissatisfaction and taxation was the Poor Conrad revolt, which began in Kernen im Remstal in the Schorndorf district, 30 km (19 mi) from Stuttgart, a wine-growing region particularly affected by economic downturn caused by poor harvests in recent years and high taxation. Despite Ulrich's repealing of the excise on meat, discontent continued to grow, forcing Ulrich to finally call a diet.[12] He held it in Tübingen on 26 June 1514 in a move that showed his paranoia of public opinion of him in the capital, and would be the first of three diets in Ulrich's reign, though representatives from 14 towns in the Duchy had met previously in Marbach am Neckar in order to effectively pacify the attending commoners.[14]

The result of that pre-meeting was the list of 41 articles that became the Treaty of Tübingen,[14] the most significant piece of legislation of Ulrich's reign,[12] at the Diet on 8 July 1514. The Estates agreed to pay Ulrich 920,000 florins over the next decade to annul his debts in exchange for requiring the consent of the Estates prior to any declaration of war, the prosecution of criminals to be instigated only with a regular legal procedure, and the right all citizens of the Duchy at will, called the Freisitz,[14] provided they met certain criteria.[15] While the relationship between the Duke and the Estates seemed to be cemented, the Dukes did not always abide by the Treaty, and the knights and prelates, who appeared at no point or at one point in the creation of the Treaty respectively, had little no involvement in it. Ironically, the Treaty, which would not be fully implemented for the rest of the 16th century, appeared to be more of a victory for Duke Ulrich, as he sought just to appease the Estates and to obtain the funds required to continue his rule, both of which he had accomplished, obliging him to ignore the treaty.[14]

Three events would come to be responsible for the demise of Duke Ulrich's first rule. The first of these would be the murder of his equerry, Hans Ritter von Hutten, in the forests of Böblingen in May 1515. Ulrich had taken a romantic interest in von Hutten's wife and, according to a later declaration the Imperial Diet of Augsburg on 19 August 1518, had become hostile towards him after Hans' marriage to Ursula von Hutten.[16] Ursula was the daughter of Thumb von Neuburg, the marshal and one of the most influential men in the ducal court, and Hans von Hutten was the cousin of Ulrich von Hutten, a famous humanist and knight who was also a firebrand publicist, and son of Ludwig von Hutten, a Franconian knight who had also served in the ducal court and was of the von Huttens, one of the most powerful lower noble families in the entire Duchy. The political fallout of this murder resulted in the immediate resignation of 18 noblemen from Ulrich's court, demands from the von Huttens for financial compensation, and fiery, printed attacks by Ulrich von Hutten.[17]

The second event was the flight of Ulrich's wife, Sabine of Bavaria, back to her family in November 1515 along with Dietrich Spät, one of Ulrich's advisers. Overnight she had unmade a match Emperor Maximilian I had arranged with her father, Duke Alphrecht.[lower-alpha 3] She had complained bitterly about the mistreatment she had experienced by Ulrich, of von Hutten's murder, and of Ulrich's refusal to pay off her debts. Her immediate family demanded immediate compensation and for Ulrich to be expelled, and to this end appealed to the Estates but were rebuked, despite Ulrich's now widespread unpopularity out of loyalty to him and a lack of influence in Württemberg on Sabine's part. The Bavarians resorted to attacking the Duchy, causing Maximilian I to intervene and call a diet in Stuttgart on 18 September 1515 to limit Ulrich's power and to create a balanced system of government. This resulted in the Treaty of Blaubeuren, which mandated that a seven-member regency would rule the Duchy for a period of six years consisting of the Landhofmeister, the Chancellor, a prelate, two nobles, and two burghers, with an eighth regent to be named by the Emperor.[17] Ulrich himself was to be dependent on this regency for counsel,[18] and he no longer had control of the Duchy, a proposition he was not in agreement with. Ulrich charged many leading members of the Ehrbarkeit, and of them killed brothers Conrad and Sebastion Breuning, Conrad Vaut, the bailiff of Cannstatt, and Hans Stickel, the Burgomaster of Stuttgart. After the executions of the Breuning brothers, Maximilian attempted to call another diet to enforce the Treaty of Blaubeuren, but it was here that he realized the fatal flaw of the treaty: it did not involve the Estates and, thanks in part to Maximilian's advanced age, they neither the will nor power to act against Ulrich.[19]

The final event that sealed the fate of Ulrich's first reign of the Duchy came eight days after Maximilian I's death on 12 January 1519, when Duke Ulrich stormed the Imperial City of Reutlingen on the pretense of avenging the recent murder of the commander of the town's fort and his wife. He made it a property of Württemberg property, with its allegiance owed to Ulrich rather than the Emperor. This entire event, the metaphorical last straw of Ulrich's reign, was in complete violation of the Treaty of Tübingen and angered the other Free Cities, most of whom were in the Swabian League, from which Württemberg had been expelled in February 1512 against the wishes of Maximilian I, who prepared for war while Ulrich coerced 80,000 florins from the Estates and received 10,000 crowns from Francis I of France in February 1519 to fund his war and repay a past debt. The man to lead the Swabian League army was the capable Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria, and his campaign would last little over two weeks. It opened with Duke Wilhelm IV attacking Hellenstein Castle on 28 March 1519, followed then by attacks on Esslingen, Uhlbach, Obertürkheim, Hedelfingen, the nunnery of Weiler Filstand, Hunddskehle Castle, Teck Castle, and finally stormed Stuttgart in April and forced Ulrich to flee. His first reign had ended, and he would not return for 15 years.[19]

Habsburg occupation

The first order of business for the Swabian League occupation was to set Württemberg's government in order, and one of the most crucial tasks to achieve this was to settle the enormous 1.1 million gulden debt,[19] and few wanted to help finance this mountainous deficit. The knights, who were at this time most able to assist, did not want to as they felt that they did not constitute an estate of the Duchy and were thus without obligation to the Duchy. Since the knights refused to pay and the Ehrbarkeit and lay citizenry had not the funds to pay, the League sold the Duchy to the new Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, on 6 February 1520 for a sum of 220,000 florins with the blessing of the Estates and on the conditions that they pay Ulrich's debts and that they defend the Duchy from any future attacks made by Ulrich. Charles V may have had some motives in the purchasing of the Duchy based on plans of Maximilian I's in 1518 of "Austrian centralization" in Swabia with "an integrated judicial system." Charles V did not, however, ever rule the Duchy himself, electing instead to proclaim the "freedom of the Estates of Württemberg" on 15 October 1520 and that it would pay him an annual levy of 22,000 florins, setting the tone of the Habsburgs' 14-year rule of Württemberg, one in which the nobility were to be empowered.[20] This government in Charles V's absence was headed by a new position, the Statthalter, a nobleman who represented the Emperor in all matters, and the reinstated Gregor Lamparter, one of the Ehrbarkeit and Chancellor at the time Ulrich had arrested that had escaped death. Charles V turned the Duchy over to Archduke Ferdinand I on 31 March 1522, who first called a diet to publicly state his support of the Treaty of Tübingen, followed by the appointment of a new Statthalter, Maximilian van Zeverbergen from the Netherlands, and Chancellor, Heinrich Winckelhofer, who was aided in the issuing of the Statthalter's orders by the regents and other commissioners.[21] Treasury officials were given much more control over the treasury than in Ulrich's reign so as to reestablish order,[22] and the Estates would help organize it like its counterpart in Austria, which was separate from the Chancery and was called the Kammer and was operated by three treasurers. This control over the treasury and state expenditure would be the most important reform of the Habsburg occupation.[23]

Government

The government of the Duchy of Württemberg was one composed of several hundred people.[24] One group, called the "Notables," or Ehrbarkeit, made up of powerful local families, was the dominant force in the local administration of the Duchy.[25][lower-alpha 4] The central government consisted primarily of a bureaucracy of these Ehrbarkeit from the regional towns that came to work and live in Stuttgart. Typically, these officials began in local or district government, and then retired to their home towns in their later years or when court was not in session, creating the "town and district" character of Württemberg's politics.[27] An oddity of the Duchy in comparison to other German states was that burghers held positions in the Duchy's central government alongside nobility, most of them holding an extensive university education, and were employed in an ever-growing number for the administrative needs of the Duchy. Despite the lower pay and prestige they enjoyed by comparison to nobility, burghers would remain their own distinct class.[28] The best example of the power wielded by the burghers in the Duchy's government, however, was to be found in the Estates, who sought always to hold the Duke to the terms of the Treaty of Tübingen, a piece of legislation that outlined the rights of the burghers and the Duke's duties to them.[26]

The foundations of the government of the Duchy of Württemberg were laid even before the elevation of the County of Württemberg in 1495. The House of Württemberg had governed the territory for centuries, but had split in half along the two branches of the family in 1442 by the Treaty of Nürtingen. When Count Eberhard V the Bearded united the two halves of the Duchy in 1482, he merged the governments of the two into the basis of the central government.[7] An important department of this government was the chancery (Kanzlei), which had existed in Württemberg since 1482 and found its headquarters in the capital, Stuttgart. The supervision of the count's court income and grain and wine had become too great for the 15th century Hofmeister and cellarer, prompting the creation of the receipt department (Zentralkasse), staffed by the territorial clerk (Landschreiber) and ducal treasurer (Kammermeister).[29] To complement this was the central financial office (Landschreiberei), in essence the government treasury that received the taxes collected across the Duchy.[30]

District government

The Ehrbarkeit held a variety of positions in local government as well as district government, which relied on a network of the Duchy's market towns, establishing a link between the town and the countryside.[26] The most powerful official in a district was the bailiff (Vogt), who governed and supervised the functions of urban government in the name of the Duke from the district seat (Amtstadt).[31] This position first appeared around 1425, but it took around seventy years for the functions of the bailiff to be fully established. By the end of the 15th century, this office had split into senior bailiff (Obervogt), typically a nobleman, and junior bailiff (Untervogt), who would preside in the absence of the senior bailiff and was usually himself a burgher. The senior bailiff, more free than his counterpart, was not restricted to serving within his own district and would sometimes advise other rulers and even the Duke. The senior bailiff was also charged with the defense of his district and so usually would reside in a castle in or near the district seat. Old noble families traditionally served in their districts, giving them experience that some would use to secure positions in the central government of the Duchy. By the end of the 17th century, the title of senior bailiff had become almost entirely honorary and only about 25 were employed by the Duchy. The junior bailiff was a much more executive officer, being charged with law and order through the district courts, and he also supervised the district's finances and the levying of new taxes. If he was unable to rectify any given situation, he would refer it to the chancery in Stuttgart,[32] and the Chancellor (Kanzler) would decide the matter.[33] This position, the link between local, district, and central government, was very common among officials who would later join the central government.[34] Two more offices completed district government: the Cellarer (Keller or Pfleger) and the Forester (Forstmeister or Waldvogt), of whom there were never more than 12. The cellarer oversaw the collection and stockpiling of the district's grain and wine, a job previously managed by the bailiff until the creation of the cellarer (this duty would sometime be performed by another chief administrative officer called the Schultheiss). The forester, a position created around 1410, was in charge of the forests in his district, enforcing the laws governing the forest that covered such things as logging and hunting. Often, he came into conflict with the citizenry, who resented the increasing taxes and restrictions placed on the forest's use.[35]

Local government

The primary power in local government were the town council and court (Rat und Gericht). The council handled the town's daily affairs while the court exercised civil jurisdiction in the town and jurisdiction of non-capital criminal affairs for the entire district. Though the bailiff was originally charged with appointing members of either organization in the 15th century, the membership of the council and court were, by the end of the 16th century, made up completely by the town's notables, people like rich artisans, merchants, and local guild members. One of the leading officials in the local government was a kind of village mayor called the Schultheiss.[35] The origins of this position date back to the 13th century, the first recorded instances being in Rottweil in 1222 and in Tübingen in 1247.[34] In that time, the town's lord (Stadtherr) chose the Schultheiss from a pool of 30 to 50 men and he governed the town according to the lord's interests. When the interests of the Scultheiss came to share those of the town's elite rather than the lord's, he created the position of bailiff in order to maintain his interests in the community. These two officials would work together for a time, but during the 15th century, the authority of the Schultheiss eroded. Despite this, he could still preside over the district court in the absence of the bailiff. Subordinate to the Schultheiss was the town's Burgomaster (Burgermeister), the only official to be elected by the citizenry and another office with its origins in the 13th century (the first documented one in Rottweil in 1283). However, popular election was still a rarity and he was typically appointed by the town council and normally from the town's notables. The Burgomaster often came into conflict with the Schultheiss as the former upheld the interests of the town council and the latter of the lord. His chief duties were the accounting of taxes, fines and other town incomes and to present an annual accounting (Gemeinderechnung) before the junior bailiff, whom he assisted in daily local administration. The number of Burgomasters throughout the Duchy was wildly inconsistent, as each town's constitution mandated how many Burgomasters the town could have and how long they served (most terms ranged from one year to a decade). In some instances, no Burgomasters were present in town and thus they only had a Schultheiss. The final office in local government was the town clerk (Stadtschreiber), who wrote up important documents for the council and would sometimes supervise the taxation of the populace. The town clerk was the link between the local and central governments, as he had to, for example, write all requests to be sent to the Duke by the citizenry (these would also have to be approved by the junior bailiff),[36] making him one of the most important people in local government.[37] He would also be expected to have a specific knowledge of the territory of the Duchy and the laws that governed it, and this would be tested by the chancery in Stuttgart whenever the clerk visited the capital.[36]

Central government

As before, the Duchy's notables had a powerful presence in the central government but burghers, in particular, came to fill many important offices by either university education, clerical expertise, or administrative experience in district and local government.[37] Burgher or noble, the many councilors in the central government had tremendous influence, even if that influence and thus the balance of power in the Duchy's administration, was subject to the whim of the ruling Duke. However, they were not entirely dependent on the Duke, as much of the actual governing was out of his hands, and the geographical location and political instability of the Duchy contributed greatly to its unique political development.[38] One of the leading burgher councilors in the central government was the Chancellor (Kanzler), a position again traceable to the 13th century, when monks worked on documents for the court.[lower-alpha 5] The Duchy's first Chancellor was a prelate who was given the position by Count Eberhard V in 1481. However, after the County's elevation to a Duchy, this position would only be held by burghers, like most of the jobs in the chancery, because of the legal knowledge required. The growing influence of the chancery meant the growing influence of the Chancellor, normally the best educated of the Duke's councilors, typically holding a doctorate in canon and civil law as well as extensive administrative power.[37] As one of the burgher elite, he was the link between the central government and local communities for settling disputes.[39] If a matter could not be solved by the town council, it would be referred to the Chancellor by the bailiff, and he would decide the matter. The Chancellor also represented the Duke for diplomatic missions and occasionally at territorial diets of the Estates. By the mid-16th century, the advisory body to the Duke, the Oberrat, created the position of Vice Chancellor (Vizekanzler) in 1556 to aid the Chancellor, by now struggling with his workload, and to substitute for the Chancellor in his absence, and to serve as the secretary for sessions of the privy council (Geheimer Rat). More than any other official in the central government, the chamber secretary, Kammersekretär, charged with the organizing the Duke's schedule, writing Ducal correspondence, and processing documents, worked solely for the Duke. This job was also always held by a burgher, as he had to have clerical expertise, but almost never had a university education. At first, the Vice Chancellor held no political power, but then Duke Christoph enlarged the role of the Kammersekretär by allowing him to advise on policies concerning the chancery, church council, and even to oversee the treasury, a right no other official but the chamber master (Kammermeister) possessed. In the reign of Duke Ludwig, he would become one of the most influential officers in the central government, assuming the role of personal adviser and close friend to the Duke, rivaling only the territorial governor, Landhofmeister in influence on policy.[33]

Following the Reformation, new positions that worked during the Visitation were created. With the help of the Ducal court and reformers Johannes Brenz, Ambrosius Blarer, and Erhard Schnepf, a powerful new, centralized ecclesiastical cabinet formed to assure the Duke's will in religious matters were felt throughout the duchy via a strict system of visitation to all of the duchy's districts. The creation of the church council, Kirchenrat, in 1553 resulted in a position only held by burghers: the church council director, or Kirchenratdirektor, who worked with the church council on Ducal policy in religious matters, helped with the appointing of local preachers and administrating of church lands, and supervised the monasteries. Supervision of the monasteries and nunneries was important to the Duchy, as the Reformation made their exorbitant spending no longer acceptable, though they were still allowed to exist in Lutheran Württemberg. The government placed levies on the "fourteen great monastic trusts,"[lower-alpha 6] and the Duke or the Estates could spend this money on the Duchy's defense or on other projects. While he supervised this revenue, his clerks recorded it account books called Kirchenkastenrechungen.[40]

Of the positions only held by nobility, most were created in the 15th century and required little or no education, paid much more than burgher, and often involved constant contact to the Duke or other nobles. Originally, the Württemberg court had a Hofmeister, but this office was broken into the offices of territorial governor, Landhofmeister, and the court steward, Haushofmeister. The most powerful of the nobles in court traditionally was the territorial governor, Landhofmeister, who served as the Duke's foremost adviser and controlled the chancery. With the creation of the chancery in 1482, the same year as the reunification of the Duchy (then County) and establishment of Stuttgart as capital, the Landhofmeister and the Chancellor worked closely together, and this association remained important until the Kammersekretär supplanted the chancellor in importance. The Haushofmeister, who once accompanied the Duke on hunting trips and managed the court income and servants, was a position that would become merely honorary, and he would soon find himself relegated to tutoring of noble children and sourcing the food consumed by the court.[41] This position was unique in that husband and wife could both serve as Haushofmeister and Haushofmesiterin, who would assist her husband and taught the female children of the nobility. A leading noble figure at the court was the Marshal, who was tasked with its defense as well as supervising the court servants (Hofgesinde). Although military experience was no longer considered a prerequisite by the reign of Duke Ludwig, it remained an important advisory position. The Kammermeister oversaw the Ducal treasury and was in this way distinct from the Landschreiber, who oversaw the general treasury. The Kammermeister was already a close adviser to the Duke, but he became even more powerful during the Habsburg occupation of the Duchy, as three were appointed to set the Duchy's finances in order. However, this title too became increasingly honorary; by the 1570s, there were long periods wherein there were no Kammermeister as the Kammersekretär had largely taken over his responsibilities. The final noble-held office in the central government was that of the Statthalter, a kind of ad hoc substitute governor. There was typically a Statthalter only in times of regency or absence of the Duchy's ruler,[42] and he became particularly important during the period 1520–1534, when the occupying Habsburgs attempted to rule the Duchy in the absence of Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand. He maintained close ties with Austria, summoning the Estates often to consent to new taxation and to raise troops for Austria during the War with the Turks. Unfortunately for the Habsburgs, the tenures of the Statthalter tended to be short. Despite this, their office would continue into the second reign of Duke Ulrich and would become especially important in the regency of Duke Ludwig.[38]

Beneath the councilors were the secretaries, clerks, and accountants who ran the bureaucracy of the Duchy and adhered to a strict discipline and worked long hours. These men held no political power of their own, but often, this was the starting place for burghers looking to climb the ladder.[43] Secretaries and clerks (Schreiber) copied and filed important documents for the various branches of the government. The growth of the central government's bureaucracy also meant the number of clerks growing from 25 in 1520 to over 80 by the end of the century. Accountants too grew in number, as the number of bookkeepers (Buchhalter), charged with maintaining a general ledger to recording and writing summaries of votes cast in privy council meetings, would be expanded greatly to fill the needs of the government. Other low-level positions included the keeper of the treasury (Gewöhlbeverwater), who curated the goods of the treasury vault such as government archives, and the message supervisor (Botenmeister), who managed the couriers of the Duchy.[44]

The Estates

The Estates (Landschaft), the largest political body in the Duchy, were an entity that had existed even before the founding of the Duchy (The first assembly of the Estates, called a Landtag, occurred in Leonberg in 1457 when Count Ulrich V summoned the notables of the towns to counterbalance the attending knights (Ritterschaft)),[45] and it consisted of representatives from several different estates (Stände): the prelates, nobles, and burgher officials. The prelates were the abbots of the fourteen monasteries of the Duchy, who were generally present at the diets as Ducal appointees after the Reformation. Roughly 30 noblemen, usually Ducal councilors or some other senior official, also regularly attended.[44] Since the Estates were intended to be the representatives of the Duchy's inhabitants, about 75% of the participants of a Diet were townsfolk,[46] though the peasantry had almost no input.[lower-alpha 7] The Estates had no means of imposing their will, and were to a certain extent dependent on the Duke to be effective. At times they were able to convince the Duke into reform, such as with the Treaty of Tübingen in 1514. During times of minority or absence of the Duke, the Estates had a large decree of control over policy and government, which they effectively lost in times of majority. Duke Ulrich, for example, rarely called Diets.[45] Of the burghers that attended the Landtag of 1520, all of them belonged to the court and council of 44 towns, all of them Ehrbarkeit. The lack of resistance on their part to Ulrich's strong government shows that the Estates had neither a strong leader and popular support nor a permanent position in the Duchy's constitution and could be easily coerced. The Estates became useful to the Duke for the payment of his debts and for the declaration of the war, and they provided the Duchy's leading inhabitants political power and a forum to debate in. The Treaty of Esslingen in 1492, which stated that 12 members of the Estates could assume rule in times of incompetence, became the basis for following compromises between the Duke and the Estates throughout the 16th centuries.[48]

The regency of Duke Ulrich was a time of transition for the Estates, as they authored a government based on collegiate principle, with four nobles acting as regents and two prelates as advisers. The Estates voiced the interests of the towns to the regency, but during the Swabian War this regency became opposed to the wishes of the local burghers, among whom the war was very unpopular. The Estates would continue to vote more men and money to the war, which would end in defeat for the Swabian League. The Estates would continue to exercise their right to approve taxation to the Duchy's frequent wars, a right that would be extremely tested during Ulrich's reign.[6]

Economy

Despite its urbanization, the Duchy's economy was very agricultural, its most important product being wine. The peasantry harvested such grains as rye, barley, hay, and oats. Other products, wool, wood, cloth, linen, and glass and metal wares, followed in importance. Frequent trading partners were the Duchy's neighbors, mostly including the south western Imperial cities like Esslingen am Neckar and Reutlingen, and the Swiss Confederation. The cities of Basel and Solothurn would also regularly extended loans to the Dukes of Württemberg. Though it had no central business hub like Ulm or Strasbourg, the Duchy was a breadbasket for its neighbors.[2]

Culture

Music

The Württemberg Hofkapelle, a term both describing the court chapel as well as the group that played within it, was founded by Duke Eberhard II during his short reign of the Duchy of Württemberg.[8]

The rules of the Baroque dukes, Eberhard Louis, Charles Alexander, and Charles Eugene, were an unstable period in the musical scene in the Duchy based at the palaces of Ludwigsburg and Stuttgart (much like the Dukes that patronized those arts) that illuminates three central themes in the history of music in the West: the emergence of the orchestra, importance of chamber music and the growing number of Italian composers and musicians employed at the courts of German princes in the 18th century. Although the Duchy was recognized by Peter H. Wilson as "one of the weaker middle ranking territories within the Empire," the Dukes went to great - and expensive - lengths by the Ducal Court to be ahead of the cultural curve. The result, in the final years of the 17th century, was an increasing awareness and then desire for French style and fashion, resulting in the employment of French musicians, adoption of new Baroque woodwinds, putting on of large-scale French-style ballets de cour called Singballete and the institution of a Lullian string band that paved the way for appearance of the orchestra at court. Even in the face of periodic French aggression in the 18th century, Duke Eberhard Louis, educated with French style and mannerisms, strove to make his court a haven for French culture.[49] At the turn of the 18th century, Württemberg's musical interests, like many other European states, began turning to Italy, which can be seen in the productions of Johann Sigismund Kusser from 1698 to 1702. Musical funding would come to a sudden end with the War of Spanish Succession and it would have an indelible impact on music at the court in later years.[50]

While very little documentation of the musical activity of the first decade of the 18th century, we know that by 1715, the membership of the Duchy's Hofkapelle was three concertmasters (German: Kapellmeister), 22 instrumentalists, 11 vocalists, and two choirboys (German: Kapellknaben) as well as an additional complement of seven trumpeters and a single kettledrummer. Two of those Kapellmeisters, Theodor Schwartzkopf and Johann Georg Christian Störl, Schwartzkopf's former pupil. These two men had a falling out and Störl attempted to have Schwartzkopf and his family ejected from the Kapellhaus, claiming that his residence was unsuitable for the practice of opera. In truth, the small Old Castle was already too small for the Duke's musical retinue, as was noted by the two Kapellmeister.[50] While in Munich during the winter of 1705–06 following the defeat of Elector Maximilian II Emanuel and his brother, Joseph Clemens, Elector-archbishop of Cologne, after their defeat at defeat at Blenheim in 1704 and subsequent exile to France in 1706,[51] he learned of the Catholic musician and composer Johann Christoph Pez, a Catholic,[52] who now was in charge of instructing the Wittelsbach children in music. Emperor Charles VI released the entire musical ensemble of the Imperial fugitives by decree in May 1706, and Eberhard Louis hired Pez as Senior concert master (German: Oberkapellmeister) of the Württemberg Hofkapelle, above both Störl and Schwartzkopf.[53] Pez expanded the size of the Hofkapelle, particularly the number of instruments used by the court and the number of court musicians who could pay more than one instrument,[53] but also dramatically shrank the importance of the Kapellknaben to the point where only two were employed by the court.[lower-alpha 8] This growth happened in spite of the ongoing War of the Spanish Succession and even Villars's invasion of the Duchy in 1707 (which caused the Ducal family to temporarily flee to Switzerland)[53] finally ended in 1709 when the Duke, increasingly short on cash because of the war and the construction of Ludwigsburg Palace,[55] issued a massive retrenchment that dramatically shrank the Hofkapelle. This strain would still be felt in 1714, and Pez commented:[56]

"...four hours of Tafelmusik, two to three and a half hours of chamber music, Tafelmusik once again, and from time to time, a ball as well, that [is a workload] eight musicians could not manage without alternation, which is what our musicians do with the utmost diligence and punctuality; one can make music with two or three people, which is also [the number of musicians] a burgher can afford, but a most Serene Ruling Duke of Württemberg providing for His Most Princely Kapelle and Hofmusik (as I understand the setting and glory of his most princely house) must have more than eight musicians belonging to his musical establishment."

— Johann Christoph Pez, Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities

Despite its small size and financial strain, Pez was still very proud of the quality of his instrumentalists,[57] however he worried about his vocalists,[58] who were not numerous and contained many Catholic members who would at times not be present, exacerbating the problem.[59] Württemberg, unlike other Lutheran German courts, found a semi-solution to a shortage of treble voices in the hiring of a succession of young, unmarried called Legr-Discantistinnen or Kapelleknaben (despite the masculinity of the term) who would receive music training with the expectation that they would become permanent members of the Württemberg establishment with an equal salary to the choirboys.[54][lower-alpha 9] It is also likely that female vocalists formed part of a French comödianten from 1713 to 1716 in a nod to the large-scale theatrical performances of the early days that the Duke called off and never returned to because of the vast amounts of money lost in the stay of Johann Sigismund Kusser in Stuttgart, and Pez (according to his own word) was required to practice with and compose for this group for many hours.[54] This group would perform in the celebrations of the Duke's hunting order, founded in 1702 and named after St. Hubert, that became one of the most important events in court life as the 18th century moved ahead, with Pez and the various components of the participating Hofkapelle lodged in and around Ludwigsburg Palace.[60]

By the second decade of the 18th century, the Singballete and operas used to celebrate previous ducal birthdays had been replaced with smaller presentations. This coincided with the shift of opinion in the court as to what extent chamber music (German: Cammer-Musique) was able to portray a ruler's wealth and sophistication and the perceptible increase in instrumental specialization in the Hofkapelle (a phenomenon also present at larger German courts), which may have been effected by the employment of foreign musicians. This process was brought about by the formalization of service at the Ducal family's country estates. By 1715, this began to cause financial hardship in Stuttgart, as the ecclesiastical bodies whom fronted the salaries of the Hofkapelle made known their disdain for paying a clearly secular facet of the court. To reduce this strain, a rotational system wherein a copyist and pianist were on call at all times with three groups consisting of a violinist, an oboist, and a string bass player alternating every four weeks.[61] These musicians were simply referred to as "court and chamber musicians," weren't appointed at a higher rank, and they were paid differently.[62][lower-alpha 10] Chamber music began to be considered a major part of the court's musical establishment, on par even with church and table music, as evidenced by various documents following Pez's death (25 September 1716) in May 1717 from Schwartzkopf and Störl that confirmed Pez's view of the Hofkapelle as a pool of multi-talented musicians who could play a wide range of instruments, and the hiring of violinist and virtuoso Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello as "director of chamber music" about a month after Pez's death. By the end of 1717, the concept of an orchestra as an institution began to solidify at the court.[63]

University

The University of Tübingen was established by the ruling dynasty in 1477.

Religion

In the 16th century, Württemberg became one of three competing southwest Imperial states vying for greater status in the region and the Empire at large. Itself Lutheran, Württemberg sparred with the Roman Catholic Duchy of Lorraine and the Calvinist Electoral Palatinate. Württemberg found allies in north and east Germany because of its Lutheran faith.[64]

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Pietism became widespread throughout the Duchy as a response to the perceived hedonism of Baroque society and attempt at a French absolutist state. They interpreted the social and natural calamities faced by the Württemberg as God's punishment for the immorality of the Ducal court and society and worked to uphold the Estates of Württemberg and co-operation between it and the Duke. After the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht that ended the War of the Spanish Succession, the Duchy enjoyed a period of peace and increasing fortune, and Württemberg Pietism's character shifted from moral and philosophical criticism of society to quiet theological contemplation.[65]

Notes

Footnotes

- Of these men, only von Fürstenberg and Spät had formal administrative positions in the central government; the other two only held advisory roles.[6]

- In 1492 and 1493 respectively, Stuttgart and Tübingen had established laws calling for the implementation of Roman and canon low in the legal system.[12]

- For this marriage she had been compensated with a sum of 64,000 florins. The consummation of this marriage netted her a further 10,000 florins.[17]

- Before the sixteenth century, only the local bailiff (Vogt) and judge (Richter) held the title of Ehrbarkeit. However, during the 16th century and its increase in the amount of urban and central government officials, the Ehrbarkeit came to encompass a growing number of administrators and their immediate families. In Württemberg, the term came to denote a spectrum of individuals ranging from rural citizens to burghers.[26]

- The Chancellor's original title was "protonotary," a term that also appeared in the Rhine Palatinate and in Baden, at nearly the same time, in 1228.[37]

- Those fourteen ecclesiastical institutions were Adelberg, Alpirsbach, Annhausen, Bebenhausen, Blaubeuren, Denkendorf, Herbrechtingen, Herrenalb, Hirsau, Königsbronn, Lorch, Maulbronn, Murrhadt, and St. Georgen. Of these, the two biggest were Maulbronn and St. Georgen.[40]

- The urban Ehrbarkeit saw little need in allowing the peasantry into the proceedings. Their position was not helped by the Poor Conrad uprising, causing leading members of the Estates to become antagonistic to the peasantry. This hostility by the Estates to the peasantry was not remote to Württemberg. Despite this, the Estates seemed to be more cognizant of the wishes of the people than in other German states.[47]

- Those two were Friedrich Ludwig Mayer (or Maier), who played the oboe, viola, and the bass violin in addition to his weak bass pitch, and Georg Heinrich Schmidbauer, a tenor who sometimes stood for his father who could also play the viola, gamba, and keyboards. They were both paid per annum 75 gulden, about a third of a typical musician's salary.[54]

- Another example of the court's relatively progressive stance on employing women was the Elisabetha Schmid, a trumpeter reported by Schwartzkopz to be able to play "quite a number of pieces" alongside her father and brother, despite knowing little about music.[54]

- A document from 20 July 1715 states that two musicians were paid 400 gulden, another four were paid 300, and the remaining five received the standard 347 gulden salary.[63]

Citations

- Marcus 2000, p. 7.

- Marcus 2000, p. 8.

- Marcus 2000, p. 37.

- Wilson 2016, p. 363:"The last of the medieval elevations occurred in 1495 when the count of Württemberg was made duke, legitimated through his possession of Teck, which had once been held by the defunct dukes of Zähringen. Thereafter, counts who were promoted simply received the title of 'prince' (Fürst) [...]."

- Marcus 2000, pp. 37–38.

- Marcus 2000, p. 41.

- Marcus 2000, p. 38.

- Marcus 2000, p. 40.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 41, 42.

- Marcus 2000, p. 42.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 42–43.

- Marcus 2000, p. 43.

- Marcus 2000, p. 43: "...the rich must share with us; we want to spear the great ones (Grossköpfe), so that their insides fall to the ground; the duke is of no use and the marshal [Thumb von Neuburg] is getting richer; now we have the sword in the hand, now the sun stands in our constellation; different advisers, district officials, bailiffs must appear, and no longer the fat ones."

- Marcus 2000, p. 44.

- Brady, Thomas A. Jr. "Treaty of Tübingen, 1514" (PDF). German History in Documents and Images.

- Marcus 2000, p. 44: Hans von Hutten had been Ulrich's "most trusted, highest and dearest servant ... until von Hutten took a wife, then ... [the duke] became unfriendly and hateful towards him."

- Marcus 2000, p. 45.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 45–46.

- Marcus 2000, p. 46.

- Marcus 2000, p. 47: "as the nobility well-suits the duchy in every way ... it will be respected; the duchy will be dependent on it; and will obey it as far as possible."

- Marcus 2000, p. 47.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 47–48.

- Marcus 2000, p. 48.

- Marcus 2000, p. 1.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 8–9.

- Marcus 2000, p. 9.

- Marcus 2000, p. 22.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 38–39.

- Marcus 2000, p. 39.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 39–40.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 9–10.

- Marcus 2000, p. 10.

- Marcus 2000, p. 14.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 10–11.

- Marcus 2000, p. 11.

- Marcus 2000, p. 12.

- Marcus 2000, p. 13.

- Marcus 2000, p. 18.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 13–14.

- Marcus 2000, p. 15.

- Marcus 2000, p. 16.

- Marcus 2000, p. 17.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 18–19.

- Marcus 2000, p. 19.

- Marcus 2000, p. 20.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 19–20.

- Marcus 2000, pp. 20–21.

- Marcus 2000, p. 21.

- Owens 2011, p. 165.

- Owens 2011, p. 166.

- Owens 2011, pp. 166–167.

- Owens 2011, pp. 169, 170.

- Owens 2011, p. 167.

- Owens 2011, p. 170.

- Owens 2011, pp. 167–68.

- Owens 2011, p. 168

- Owens 2011, p. 168: "...all are experienced on three, four, to five different types of instruments, [and] also bow [on string instruments] with clean French characteristics so nicely and unitedly together, that I dare to challenge any musical establishment in the [Holy] Roman Empire, even if they are five times the size of us, to be better than us." —Johann Christoph Pez

- Owens 2011, p. 169: "We have so few vocalists, that we can only just fill a quartet with its ripieno in the Hofkapelle; should one or the other become ill, this cannot take place either, [and while] it is possible to perform something with only two or three [vocalists], this is not really appropriate for such a distinguished Most Princely Kapelle, and I am often forced to seek out those instrumentalists who can sing when I want to fill all vocal parts." —Johann Christoph Pez

- Owens 2011, p. 169

- Owens 2011, pp. 170–71.

- Owens 2011, p. 171.

- Owens 2011, pp. 171–172.

- Owens 2011, p. 172.

- Raitt 1993, p. x.

- Fulbrook 1983, p. 7.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Württemberg". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Fulbrook, Mary (1983). Piety and Politics: Religion and the Rise of Absolutism in England, Württemberg, and Prussia. University of Cambridge Press. ISBN 0-521-25612-7.

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (1995). Court, Cloister, and City: The Art and Culture of Central Europe, 1450-1800. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-42729-3.

- Marcus, Kenneth H. (2000). Politics of Power: Elites of an Early Modern State in Germany. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-2534-7.

- Owens, Samantha; Reul, Barbara M.; Stockigt, Janice B., eds. (2011). Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities. Foreword by Michael Talbot. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-598-1.

- Raitt, Jill (1993). The Coloquy of Montbéliard: Religion and Politics in the Sixteenth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507566-8.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03634-5.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05809-5.

.svg.png.webp)