History of Aligarh Muslim University

The history of Aligarh Muslim University begins with the Aligarh movement, which was a movement to establish a Western style of education for the Muslims of British India. The movement was pioneered by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, who founded the Muhammadan Anglo Oriental College in Aligarh. Sir Syed retired at Aligarh, and undertook the charge of raising funds for the college, and supervising the construction of the campus.

After Sir Syed's death in 1898, a fund was instituted to convert the college into a university. With the rise of the Khilafat movement during the first world war, the college became a center of Muslim political activity. In 1920, the college was converted to the Aligarh Muslim University by an act of the British government. In 1935, the engineering college was established. The university remained a center of politics, with both the Indian independence movement and the Pakistan movement gaining traction at the university.

After Indian independence and partition in 1947, a large number of students and staff migrated to the newly created Pakistan. Zakir Husain was appointed vice-chancellor to steer the university during this tumultuous period. The medical college was established in 1962, and the dental college in 1996. In the 21st century, degree-granting centers of the university were established in Malappuram, Murshidabad, and Kishanganj.

Aligarh movement

Background

The failure of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 against company rule in India led to the collapse of the last vestige of the Mughal empire. In the post-mutiny period, the Muslim upper classes and ulema (scholars) in India were increasingly conservative, and suspicious and hostile towards the British government, as well as Western-style education introduced by the British.[1]

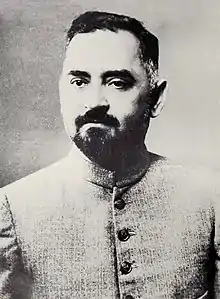

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, a who was a scholar and judge, was convinced that adopting Western education and fostering loyalty to the British empire was imperative to improve the situation of the Muslims of India. He started a movement, which would later be termed as the Aligarh movement, to reform Muslim society and remove the antagonism towards Western education and government service. He established a schools at Muradabad and Ghazipur, and in 1863, established scientific society for Muslims at Aligarh. The movement attracted prominent scholars including Jai Kishan Das, Moulvi Samee Ullah Khan, Khwaja Muhammad Yusuf, and Zakaullah Dehlvi.[1]

Setting up of a college at Aligarh

On 26 December 1870, the "Committee for the Better Diffusion and Advancement of Learning among the Muhammadans of India" was set up, with Sir Syed as its secretary. The members of this committee included several ruling princes, government officials, and wealthy landowners. The committee solicited essays written by Muslims in Urdu to summarize the reasons for the underrepresentation of Muslims among government schools and colleges, decline of the old systems of education, and the lack of modern scientific education among the Muslims.[1]

In 1872, Sir Syed presented a report, known as the Benares Committee Report, which consisted of the findings of the committee. The initial sections outlined the essay competition, and contained discussions by the members of the committee about the points in the essays. In the third part, among other suggestions, it was proposed that a large college, with three departments— the departments of English, Urdu, and Arabic and Persian. This college would function along the lines of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Copies of the report were sent to government officials and other influential persons, and drew praise from the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of the North-Western Provinces, both of whom contributed to the college fund. The orthodox Muslims and the ulema remained opposed to the idea, and issued fatwas ruling it unlawful to contribute to the fund.[1]

In a meeting held on 8 November 1872, Aligarh was chosen as the site for the college. The committee identified a plot troops from the old cantonment used to parade, which was long abandoned. In 1874, John Strachey was made governor of the United Provinces. He allotted the plot, on the condition that the college buildings would be taken over by the government in case the college shut down. With the land allotted, Moulvi Samee Ullah Khan made necessary arrangements, and the college was founded in 1875.[1]

Muhammadan Anglo Oriental College (1875-1920)

The official opening ceremony of the school took place on the birthday of Queen Victoria, on May 24, 1875. In 1876, Sir Syed retired and permanently settled down at Aligarh. The foundation stone was laid by Lord Lytton on January 8, 1877.[1] Henry George Impey Siddons was appointed as the first principal of the college.

Sir Syed traveled across India in order to raise funds for the college, and by 1880, had secured considerable grants from the Nizam of Hyderabad, Maharaja of Patiala, Nawab of Rampur, and Salar Jung I. He also personally oversaw the construction of buildings at the campus. Construction of the Jama Masjid, designed in a Mughal style, began in 1879 although it wouldn't be inaugurated until 1915.[2]

Efforts were made to inculcate Western mannerisms among the boarders. The use of dentrifice, laced or thin clothing, the use of henna to dye palms, and long curls, were banned. The cricket club was established in 1878, and the Siddons Union Club in 1884 modeled after Cambridge Union.[1]

In 1898, Sir Syed died, and was buried at a tomb near the mosque on campus. Two factions emerged after his death,

After Beck's death in 1899, Theodore Morrison succeeded him as principal. He outlined a proposal to convert the institution into an Arabic college, with the intention to recruit from Aligarh candidates to fill positions in the British possessions in the Middle East. The proposal ended in the creation of a chair in Arabic.

Women's education

Sir Syed was opposed to modern education for Muslim women.[5] After his death, Sheikh Abdullah raised the issue of establishing a girls' school.

Campaign to establish a Muslim university

In 1898, on the recommendation of Sahibzada Aftab Ahmad Khan, the Sir Syed Memorial Fund was established with the objective of clearing the college's debts and ultimately converting the college into a university.[6]

Colonial period (1920-1947)

On 1 December 1920, the Aligarh Muslim University Act came into effect, converting the college into the Aligarh Muslim University. The Raja of Mahmudabad was the inaugural vice-chancellor, while Sultan Jahan, Begum of Bhopal and Aga Khan III were made chancellor and pro-chancellor respectively. The government made an annual grant of Rs. 100,000 for the university.[6][7]

Politics

In 1920, the non-cooperation movement was launched by Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi delivered a speech at the university on 12 October. Subsequently, members of the Khilafat movement including Shaukat Ali, Mohammad Ali Jauhar, and Abul Kalam Azad arrived at the university, and a number of students (estimates ranging from 200 to 700) joined the movement and left Aligarh to enroll themselves at Jamia Milia Islamia. Throughout the 1920s and until the mid-1930s, Indian nationalism remained popular at the university and the student union was largely pro-Congress.[8][9]

In 1937, the All India Muslim Students Federation was established. Support for the Muslim League had grown at the university. Teachers with "socialistic" and "atheistic" ideas were dismissed, purdah was reintroduced at campus, and "dangerous" books on rationalism and religion were removed from the Lytton Library. By the 1940s, with the passing of the Lahore resolution and several speeches given by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Liaqat Ali Khan at the campus, the student body became overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Pakistan movement. The student magazine regularly carried articles in favor of Jinnah and Pakistan.[8] In 1941, Ziauddin Ahmad, who had joined the Muslim League, was elected vice-chancellor.[9]

Post-independence (1947-present)

Financial crisis and modernization

By 1947, the university had come to primarily depend on students' fees for funding, with some additional funding coming from the British government and Muslim princely states such as Hyderabad. With Indian independence and partition in 1947, a large number of students and staff, including vice-chancellor Zahid Husain migrated to Pakistan. The number of students, which had been in excess of 5000 in 1946–7, had fallen to 1000 in 1949. The princely states were also integrated into India and Pakistan, with their rulers losing power. As such, the university fell into considerable financial crisis.[10]

The university's image was tainted by the association with the Pakistan movement.[11] Rumors were circulated of Pakistani officials recruiting students at Aligarh, and of arms and ammunition stored on the campus. Demands were also made in the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly and in parliament to shut down the university.[8] On campus, discipline suffered and hooliganism became rife, and the university administration, in an effort to display loyalty to the government, suppressed political dissent. Communist students and faculty members, including notable professors Zahida Zaidi and Iqtidar Alam Khan, were arrested.[12]

In 1948, Zakir Husain was appointed with vice-chancellor and tasked with modernizing the university by Abul Kalam Azad, the minister of education. Husain, who took regular charge in 1950 following a long absence due to illness, began the process of restoring discipline. The communist students, on their release from prison, were readmitted. He also began filling the vacancies among teaching positions by inviting eminent professors from all over India to join the university. These appointments included the professors Abdul Aleem, Saiyid Nurul Hasan, D. P. Mukerji, and Piara Singh Gill.[12]

Aligarh University (Amendment) Act, 1951

The Aligarh University Amendment Act of 1951 was passed.[10] The university was brought under direct control of the central government, and

Minority status

In 1965, a student riot broke out and vice-chancellor Ali Yavar Jung was injured. On M. C. Chagla's recommendations, an ordinance was passed which suspended the university constitution and reduced the university court to an advisory body.[13][11][14]

21st century

In 2020, the university centenary celebrations were held, primarily online due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[15] The Centenary Gate was built to mark the occasion.[16]

Controversies

In 2014, the death of professor Ramchandra Siras. In 2016, violence broke out between two student groups, resulting in one death. In 2019, during the Citizenship Amendment Act protests, the protests at the university were violently quelled, with about 60 students injured.[17]

Off-campus centers

In 2008, the university submitted a proposal to set up five centers of the university. The government sanctioned funds to set up the centers at Malappuram and Murshidabad, which were set up in 2010.[18][19] In 2013, the center at Kishanganj was established.

References

- Hasan, Rahmani B.M.R. (1959). "The educational movement of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, 1858-1898" (PDF).

- "How Taj Mahal and Aligarh's Jama Masjid – Built 250 Years Apart – Share a Calligrapher". The Wire. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- Akhtar, Shamim (2018). "Aligarh: From College to University, 1898-1920". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 79: 620–624. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Ahmed, Nasreen; Ahmad, Nasreen (2005). "Muslim Female Education: Role of Sheikh Abdullah Vis-À-Vis the Aligarh Movement-(1906-1942)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 66: 1228–1240. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Ahmed, Nasreen (2007). "Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Muslim Female Education: A Study in Contradictions". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 68: 1104–1111. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Minault, Gail; Lelyveld, David (1974). "The Campaign for a Muslim University, 1898-1920". Modern Asian Studies. 8 (2): 145–189. ISSN 0026-749X.

- "History of Aligarh Muslim University". Frontline. 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- Hasan, Mushirul. "The Local Roots of the Pakistan Movement: The Aligarh Muslim University".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Akhtar, Shamim (2008). "Aligarh Muslim University and National Politics 1927-47". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 69: 587–591. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Akhtar, Shamim (2005). "University in Transition Under Freedom: A.M.U., 1947-1960". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 66: 1476–1480. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Hasan, Mushirul (2002). "Aligarh Muslim University: recalling radical days". India International Centre Quarterly. 29 (3/4): 47–59. ISSN 0376-9771.

- Akhtar, Shamim (2016). "Aligarh Muslim University: A Study of the Critical Period of Transition". Social Scientist. 44 (7/8): 79–85. ISSN 0970-0293.

- Wright, Theodore P. (1966). "Muslim Education in India at the Crossroads: The Case of Aligarh". Pacific Affairs. 39 (1/2): 50–63. doi:10.2307/2755181. ISSN 0030-851X.

- Akhtar, Shamim (2009). "Aligarh Muslim University, a 'Minority Institution' — Agitation, Legislation and the Law Courts, 1965-2009". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 70: 1169–1180. ISSN 2249-1937.

- "PM Modi to attend centenary celebrations of Aligarh Muslim University today". mint. 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- "AMU VC urged to name centenary gate after Sardar Patel or Ambedkar or Ashfaqullah Khan". The Times of India. 2020-09-25. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- "Citizenship Act: University students across country protest in solidarity with Jamia Millia, AMU". The Hindu. 2019-12-16. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- "AMU centre: PM to talk to Sibal". The Times of India. 2012-08-14. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "A historic moment for Malabar". The Hindu. 2010-10-26. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2023-07-30.