History of Chișinău

Chișinău has a recorded history that goes back to 1436. Since then, it has grown to become a significant political and cultural capital of South East Europe. In 1918 Chișinău became the capital of an independent state, the Moldavian Democratic Republic, and has been the capital of Moldova since 1991.

Foundation of the town

Founded in 1436 as a monastery village, the city was part of the Moldavian Principality. Chișinău was mentioned for the first time in 1436, when Moldavian princes Ilie and Ştefan gave several villages with the common name Cheseni near the Akbash well to one feudal lord Oancea for his good service. That year, Stephen III of Moldavia signed the donation to his uncle Vlaicu, who became the owner of the village Chișinău near the well Albișoara.

The second documentary attestation (this time about the village Chișinău) dates with the chronicles from 1466. Over the next centuries Chişinău's population steadily grows and at the beginning of the 19th century it had 7,000 inhabitants.

Măzărache Church is considered to be the oldest Chișinău, erected by Vasile Măzărache in 1752. It is a monument built according to the typical indigenous medieval Moldavian architecture of the 15-16th centuries; the church was built on the place on a fortress destroyed by the Ottomans in the 17th century. The stone block marking the location of the water spring that gave name to Chișinău is set at the foot of the hill upon which stands Măzărache Church. The name of the spring - "chisla noua" - is believed to be the archaic Romanian for "new spring".

During the Russo-Turkish Wars Chișinău was twice set on fire, in 1739 and 1788.

Built by the boyar Constantin Râşcanu in 1777, Râşcani Church stands top of the hill overlooking the Bâc River. At the time it was built, the Bâc River was navigable and formed a large reservoir in front of the church. There is a graveyard near the church in which some famous Moldavian personalities are buried.

In 1812 Chișinău came under Russian imperial administration. Having got an official status of town in 1818, Chişinău became a centre of the Bessarabian district and since 1873 the centre of the Bessarabian province. If from 1812 till 1818 the Chişinău population had increased from 7 up to 18 thousand people, by the end of the 19th century it had grown up to 110,000. The growth of population was due to the immigrants from Russian Empire. In 1856, Chişinău was the Russian Empire's fifth biggest city, after Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, and Riga.

The mayor of Chişinău office was established in 1817 as City Duma and its first mayors there were the captain Anghel Nour (1817–1821). Gavril Bănulescu-Bodoni was Metropolitan of Chişinău between 1812 and 1821. The Ştefan cel Mare Central Park was originally laid out in 1818.

Industrial age

By 1834, an imperial townscape with broad and long roads had emerged as a result of a generous development plan, which divided the city roughly into two areas: The old part of the town – with its irregular building structures – and a newer City Center and station. Between 26 May 1830 and 13 October 1836 the architect Avraam Melnikov established the 'Catedrala Naşterea Domnului'. In 1840 the building of the Triumphal Arch, planned by the architect Luca Zaushkevich, was completed.

Since 1983 the National History Museum of Moldova has housed in a building erected in 1837. Initially the building was the headquarters of the City Duma, but in 1842 it became the Gymnasium (High School) for Boys No. 1 in Chişinău.

On 28 August 1871 Chişinău was linked by rail with Tiraspol and in 1873 with Cornești. Chişinău-Ungheni-Iaşi railway was opened on 1 June 1875, in preparation for the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). The town played an important part in the war between Russia and Ottoman Empire, as the main staging area of the Russian invasion.

One of the most known mayors of Chişinău was Carol Schmidt, who led the city between 1877 and 1903. Alexander Bernardazzi was an important architect who built St. Teodora de la Sihla Church (1895) and Chişinău City Hall (1901).

A statue of Pushkin, who used to stroll the Ştefan cel Mare Central Park grounds in the early 1820s, was designed by Alexander Opekushin and erected in 1885, making Chişinău the second city after Moscow to have a Pushkin monument. Originally funded by the Chişinău inhabitants, it is the oldest surviving monument in the city.

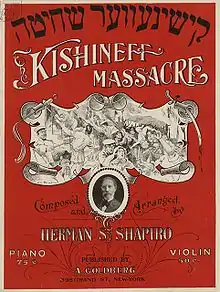

Pogrom and pre-revolution

In the late 19th century, especially due to growing anti-Semitic sentiment in the Russian Empire and better economic conditions, many Jews chose to settle in Chişinău. Its population had grown to 92,000 by 1862 and to 125,787 by 1900. By the year 1900, 43% of the population of Chişinău was Jewish – one of the highest numbers in Europe.

A large anti-Semitic riot took place in the town on 6–7 April 1903, which would later be known as the Kishinev pogrom. The rioting continued for three days, resulting in 47–49 Jews dead, 92 severely wounded, and 500 suffering minor injuries. In addition, several hundred houses and many businesses were plundered and destroyed. The pogroms are largely believed to have been incited by anti-Jewish propaganda in the only official newspaper of the time, Bessarabetz (Бессарабецъ). The reactions to this incident included a petition to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia on behalf of the American people by the US President Theodore Roosevelt in July 1905.[1]

On 22 August 1905 another violent event occurred, whereby the police opened fire on an estimated 3,000 demonstrating agricultural workers. Only a few months later, on 19–20 October 1905, a further protest occurred, helping to force the hand of Nicholas II in bringing about the October Manifesto. However, these demonstrations suddenly turned into another anti-Jewish pogrom, resulting in 19 deaths.[1]

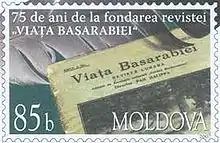

Basarabia was the first Romanian language newspaper to be published in Bessarabian guberniya of the Russian Empire in 1906–1907. In March 1907, the newspaper published the Romanian patriotic song "Deşteaptă-te, române!" and was closed. Viaţa Basarabiei was a more moderate attempt to continue Basarabia's work, but in May 1907, it also ceased its publication. Luminătorul was founded in 1910 and Glasul Basarabiei in 1913. Basarabia Reînnoită and Făclia Ţării were closed at the request of the Russian authorities soon after the apparition.

World War I

Cuvânt moldovenesc was founded in June 1914 by Nicolae Alexandri and with the financial support of Vasile Stroescu. Soon after the February Revolution, Vasile Stroescu managed to persuade all major Bessarabian factions to leave internal fights and at four day meeting (28 March [O.S. 15 March]–30 March [O.S. 17 March] 1917) the National Moldavian Party was created. In April 1917 the party leadership was elected. It was headed by Vasile Stroescu, having among its members Paul Gore (a renowned conservative), Vladimir Herța, Pan Halippa (a renowned socialist), Onisifor Ghibu. Among the leaders of the party were general Matei Donici, Ion Pelivan, arhimandrit Gurie Grosu, Nicolae Alexandri, Teofil Ioncu, P. Grosu, Mihail Minciună, Vlad Bogos, F. Corobceanu, Gheorghe Buruiană, Simeon Murafa, Al. Botezat, Alexandru Groapă, Ion Codreanu, Vasile Gafencu.

During the World War I, other publications were: Şcoala Moldovenească, Cuvânt moldovenesc (magazine), România Nouă, Ardealul, Sfatul Țării.

On 18 January [O.S. 5 January] 1918, Bolshevik troops occupied Chişinău, and the members of both Sfatul Țării and the Council of Directors fled, while some of them were arrested and sentenced to death. On the same day, a secret meeting of Sfatul Țării decided to send another delegation to Iaşi and ask for help from Romania. The Romanian government of Ion I. C. Brătianu decided to intervene, and on 26 January [O.S. 13 January] 1918, the 9th Romanian Army under Gen. Broşteanu entered Chişinău. The Bolshevik troops retreated to Tighina, and after a battle retreated further beyond the Dniester.

For the first time in his history, Chişinău became the capital of an independent state on 6 February [O.S. 24 January] 1918, when Sfatul Țării proclaimed the independence of the Moldavian Democratic Republic.

Interwar period

Between 1918 and 1940 the center of the city undertook large renovation work. The Capitoline Wolf was opened in 1926 and in 1928 the Stephen the Great Monument, by the sculptor Alexandru Plămădeală, was opened.

The first society of the Romanian writers in Chişinău was formed in 1920, among the members were Mihail Sadoveanu, Ştefan Ciobanu, Tudor Pamfile, Nicolae Dunăreanu, N.N.Beldiceanu, Apostol D.Culea.

The first scheduled flights to Chişinău started on 24 June 1926, on the route Bucharest – Galaţi – Iaşi – Chişinău. The flights were operated by Compagnie Franco-Roumaine de Navigation Aérienne - CFRNA, later LARES.[2] The airport was near Chişinău, at Bulgarica-Ialoveni. This first flight Chişinău-Bucharest was marked by the launch of a postal stamps.

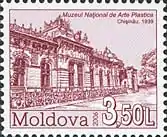

On 1 January 1919 the Municipal Conservatoire (the Academy of Music) was created in Chişinău, in 1927 - the Faculty of Theology, in 1934 the subsidiary of the Romanian Institute of social sciences, in 1939 - municipal picture gallery. The Agricultural State University of Moldova was founded in 1933 in Chişinău. The Museum of Fine Arts was founded in 1939 by the sculptor Alexandru Plămădeală. Gurie Grosu was the first Metropolitan of Bessarabia.

Viaţa Basarabiei was founded in 1932 by Pan Halippa and Misionarul in 1929. Radio Basarabia was launched on 8 October 1939, as the second radio station of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company. Writer and Journalist Bessarabian Society took an institutionalized form in 1940. First Congress of the Society elected as president Pan Halippa as Vice President Nicolae Spătaru, and as secretary general Nicolae Costenco.

In the interwar period mayors of Chişinău were Vladimir Herța, Teodor Cojocaru, I. Levinski, Vasile Bârcă, Gherman Pântea, Nicolae Bivol, Sebastian Teodorescu, Ion Negrescu, Constantin Ionescu, Dimitrie Bogos, Ion Costin, Alexandru Sibirski, Constantin Dardan, Vladimir Cristi, Anibal Dobjanski. Those years the quantity of the city population was not increasing, and in June 1941 Chişinău had 110,000 people.

World War II

In the chaos of the Second World War Chişinău was almost completely destroyed. This began with the Soviet occupation by the Red Army on 28 June 1940. As the city began to recover from the takeover, a devastating earthquake occurred on 10 November 1940. The epicenter of the quake, which measured 7.3 on the Richter scale, was in eastern Romania and subsequently led to substantial destruction in the city.

After scarcely one year, the assault on the newly created Moldovan SSR by the German and Romanian armies began. Beginning with July 1941 the city suffered from large-scale shooting and heavy bombardments by Nazi air raids. On 16 July 1941 the Romanian flag was hoisted over the dome of the 'Catedrala Naşterea Domnului'. The Red Army resistance in Chişinău fell on 17 July 1941. Michael of Romania and Ion Antonescu visited Chişinău on 18 August 1941.

Following the occupation, the city suffered from the characteristic mass murder of its predominantly Jewish inhabitants. As had been seen elsewhere in Eastern Europe, the Jews were transported on trucks to the outskirts of the city and then summarily shot in partially dug pits. The number of Jews murdered during the initial occupation of the city is estimated at 10,000 people.[3]

As the war drew to a conclusion, the city was once more pulled into heavy fighting as German and Romanian troops retreated. On 24 August 1944 the Soviet warriors entered the city as a result of the Jassy-Kishinev Operation.

In the Soviet Union

After the war, Bessarabia was fully integrated into the Soviet Union. Most of Bessarabia became the Moldavian SSR with Chişinău as its capital; smaller parts of Bessarabia became parts of the Ukrainian SSR. Soon after the Soviet occupation of 1940, the political and social elite was deportated by the Soviet authorities. Formers mayors of Chişinău like Teodor Cojocaru and Pantelimon V. Sinadino died under custody in Soviet prisons. After the Soviet occupation, the Capitoline Wolf and the Monument to Simion Murafa, Alexei Mateevici and Andrei Hodorogea were destroyed in 1940 by the Soviet authorities.[4][5][6] Anti-Soviet organizations such as Democratic Agrarian Party, Freedom Party, Vocea Basarabiei were severely reprimanded.

In the years 1947 to 1949 the architect Alexey Shchusev developed a plan with the aid of a team of architects for the gradual reconstruction of the city. If in 1944 Chişinău only had 25,000 inhabitants, by 1950 it had had 50,000. There were constructed large-scale housing and palaces in the style of Stalinist architecture. This process continued under Nikita Khrushchev, who called for construction under the slogan "good, cheaper and built faster". In 1971 the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union adopted a decision "On the measures for further development of the city of Kishinev", which secured more than one billion roubles in investment from the state budget,.[7] The new architectural style brought about dramatic change and generated the style that dominates today, with large blocks of flats. The terminal of the Chişinău International Airport was built in 1970 and reconstructed in 2000. A 17-story administrative building was erected in the 1980s in Central Chişinău.

The Moldova State University was created in 1946, Academy of Sciences of Moldova in 1949, Chişinău Botanical Garden in 1950, «Moldova-Film» in 1957, Luceafărul Theatre in 1960. The National Palace, Chişinău was opened in 1974, the Organ Hall on 15 September 1978, the new building of the National Opera-House in 1980, the Moldovan State Circus in 1982.

The idea of a sculptural complex in Central Chişinău was launched by Alexandru Plămădeală in the 1930s, but just during the Khrushchev Thaw, the Alley of Classics was unveiled on 29 April 1958. The first television from Chişinău, Moldova 1, was launched on 30 April 1958 at 7:00 pm. Nicolae Lupan was the first chief redactor of TeleRadio-Moldova. Union of Journalists of Moldova was formed in 1957.

Between 1969 and 1971, a clandestine National Patriotic Front was established by several young intellectuals in Chişinău, totaling over 100 members, vowing to fight for the establishment of a Moldavian Democratic Republic, its secession from the Soviet Union and union with Romania. In December 1971, the leaders of the National Patriotic Front, Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr, Gheorghe Ghimpu, Valeriu Graur, and Alexandru Şoltoianu were arrested and later sentenced to long prison terms.[8]

Literatura şi Arta was a publication of the Moldovan Writers' Union founded in 1977; also, Sud-Est (magazine) was founded in 1977.

In 1989–91, the Stephen the Great Monument was the focal point of meetings and clashes between anti Soviet activists and pro-Soviet supporters. In 1990, Romania donated a new copy of Capitoline Wolf; the statue was unveiled in front of the National History Museum of Moldova on 1 December 1990.

At the end of the soviet rule were established new publication as Glasul, Deşteptarea, Ţara, Sfatul Țării, Limba Română. The Popular Front of Moldova was formed in 1989.

After independence

.jpg.webp)

In 1990 the office of mayor was reestablished in the Republic. In 1990 Nicolae Costin became the first elected mayor of Chişinău. Many streets of Chişinău are named after historic persons, places or events. Independence from the Soviet Union was followed by a large-scale renaming of streets and localities from a Communist theme into a national one. The first diplomatic mission in Chişinău, the Romanian Embassy, was opened on 20 January 1992. BASA-press was the first independent news agency in Chişinău.

From 1994, under Serafim Urechean, Chişinău saw the construction and launch of new trolleybus lines, as well as an increase in capacities of existing lines, in order to improve connections between the urban districts.

In 1995, elections for the post of mayor of Chişinău were held on 10 July, 24 July, 27 November, and 11 December.

On 7 October 2002 and 8–9 October 2009, in Chişinău were held summits of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Delegation of the European Union to Moldova was opened in 2007.

The Memorial to victims of Stalinist repression and the Monument to Doina and Ion Aldea Teodorovici were opened in the 1990s and the Monument to the Victims of the Soviet Occupation was opened in 2010.

After the independence were established new publication as Gazeta Românească, Jurnal de Chişinău, Moldova Suverană, Timpul de dimineaţă, Moldavskie Vedomosti, Ziarul de Gardă. Formed in 2000, Vocea Basarabiei moved to Chişinău in 2005. In 2010 were established two 24-hour News TV stations, Jurnal TV and Publika TV.

2009 civil unrest

The 2009 civil unrest began on 7 April 2009, after the results of the 2009 Moldovan parliamentary election were announced. Demonstrators protested over fraud claims in elections, which saw the governing Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova win a majority of seats. Valeriu Boboc, Ion Ţâbuleac, Eugen Ţapu, and Maxim Canişev died during the protests. In the aftermath, a decision was taken to erect a Monument of Liberty; however, as of January 2014, no construction has taken place.

Population

If from 1812 till 1818 the Chişinău population had increased from 7 up to 18 thousand people, by the end of the 19th century it had grown up to 110,000. The growth of population was due to the immigrants from Russian Empire. In the late 19th century, especially due to growing anti-Semitic sentiment in the Russian Empire and better economic conditions, many Jews chose to settle in Chişinău. Its population had grown to 92,000 by 1862 and to 125,787 by 1900. By the year 1900, 43% of the population of Chişinău was Jewish. In the interwar period the quantity of the city population was not increasing, and in June 1941 Chişinău had 110,000 people. The birth of the 500,000 Chişinău inhabitant was celebrated in 1979.

The population of the city is 592,900 (2007) which grows to 911,400 in the entire metropolitan area.

| City of Chişinău Population by year | |

|---|---|

| 1812 | 7,000 |

| 1818 | 18,500 |

| 1828 | 21,200 |

| 1835 | 34,000 |

| 1844 | 52,100 |

| 1851 | 58,800 |

| 1861 | 93,400 |

| 1865 | 94,000 |

| 1870 | 102,400 |

| 1897 | 108,500 |

| 1900 | 125,787 |

| 1902 | 131,300 |

| 1912 | 121,200 |

| 1913 | 116,500 |

| 1919 | 113,000 |

| 1923 | 113,000 |

| 1930 | 114,800 |

| 1939 | 112,000 |

| 1941 | 110,000 |

| 1950 | 134,000 |

| 1959 | 216,000 |

| 1960 | 226,900 |

| 1963 | 253,500 |

| 1970 | 356,300 |

| 1972 | 400,000 |

| 1979 | 500,000 |

| 1980 | 519,200 |

| 1984 | 614,500 |

| 1989 | 661,400 |

| 1991 | 676,700 |

| 1992 | 667,100 |

| 1993 | 663,400 |

| 1996 | 661,900 |

| 2004 | 664,204 |

| 2007 | 592,900 |

| Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 1960 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 2004 | |

| new borns | 28,5 | 20,0 | 16,4 | 15,0 | 14,2 | |

| deaths | 11,3 | 5,8 | 6,9 | 7,0 | 6,8 | |

| natural increase of population | 17,2 | 14,2 | 9,6 | 8,0 | 7,4 | |

| marriages | 16,8 | 12,9 | 11,8 | 10,7 | 9,6 | |

| divorces | 0,9 | 2,7 | 5,7 | 6,1 | 6,9 | |

Etymology

According to one version, the name comes from the archaic Romanian word chişla (meaning "spring", "source of water") and nouă ("new"), because it was built around a small spring. Nowadays, the spring is located at the corner of Pushkin and Albişoara streets.[9]

An alternative version, by Ştefan Ciobanu holds it, that the name was formed the same way as the name of Chişineu (alternative spelling: Chişinău) in Western Romania, near the border with Hungary. Its Hungarian name is Kisjenő, from which the Romanian name originates.[10] Kisjenő in turn comes from kis "small" + the "Jenő" tribe, one of the seven Hungarian tribes that entered the Carpathian Basin in 896 and gave the name of 21 settlements.[11]

Chişinău is also known in Russian as Кишинёв (Kishinyov). It is written Kişinöv in the Latin Gagauz alphabet. It was also written as "Кишинэу" in the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet in Soviet times. Historically, the English language name for the city, "Kishinev", was based on the modified Russian one because it entered the English language via Russian at the time Chişinău was part of the Russian Empire (e.g. Kishinev pogrom). Therefore, it remains a common English name in some historical contexts. Otherwise, however, the Romanian-based "Chişinău" has been steadily gaining wider currency, especially in the written language.

Gallery

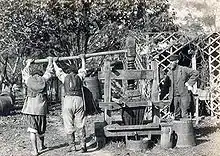

Chişinău bublik seller

Chişinău bublik seller Chişinău home brewed beer seller

Chişinău home brewed beer seller Chişinău pastry shop visitors

Chişinău pastry shop visitors Agricultural exhibition jury 1889: Carol Schmidt (center) is reading

Agricultural exhibition jury 1889: Carol Schmidt (center) is reading Chişinău water carrier, about 1900

Chişinău water carrier, about 1900.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Gothawagen ET54

Gothawagen ET54.jpg.webp) Organ Hall (Sala cu Orgă)

Organ Hall (Sala cu Orgă)

Chişinău about 1900

Chişinău about 1900

See also

References

- Virtual Kishinev Archived 2018-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 23 December 2007

- Airline companies in Rumania (1918-1945)

- "Memories of the Holocaust: Kishinev (Chisinau) (1941-1944)" from jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- Declaraţie privind restabilirea monumentului înălţat în grădina Catedralei în memoria eroilor naţionali: Simion Murafa, Alexei Mateevici şi Andrei Hodorogea

- Portrete notorii

- Mario-Ovidiu Oprea, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES

- Architecture of Chişinău Archived 2010-05-13 at the Wayback Machine on Kishinev.info, Retrieved on 2008-10-12

- Unionişti basarabeni, turnaţi de Securitate la KGB Archived 2009-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Romanian) History of Chişinău Archived 2003-07-22 at the Wayback Machine on Kishinev.info, Retrieved on 2008-10-12

- (in Romanian) Istoria Orasului Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- http://ganymedes.lib.unideb.hu:8080/dea/bitstream/2437/78065/2/de_882.pdf Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Annette M. B. Meakin (1906), "Kisheneff", Russia, Travels and Studies, London: Hurst and Blackett, OCLC 3664651, OL 24181315M

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 836.

External links

- www.chisinau.md – official site of Chişinău (in Romanian);

- www.monument.sit.md – Architecture of historical Chisinau (in Romanian)

- oldchisinau.com – Historical Chisinau in photos (in Russian)

- – Chisinau. Jewish Cemetery.Synagogue.Monuments (in English)