History of Columbia University

The history of Columbia University began before it was founded in 1754 in New York City as King's College, by royal charter of King George II of Great Britain. It is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, and the fifth oldest in the United States.

Founding of King's College

The period leading up to the school's founding was marked by controversy, with various groups competing to determine its location and religious affiliation. Advocates of New York City met with success on the first point, while the Church of England prevailed on the latter. However, all constituencies agreed to commit themselves to principles of religious liberty in establishing the policies of the College.[1]

Although the City of New York had come under the control of the English in 1674, no serious discussions as to the founding of a university began until the early eighteenth-century. This delay is often attributed to the multitude of languages and religions practiced in the province, which made the founding of a seat of learning difficult. Colleges during the colonial period were regarded as a religious, no less a scientific and literary institution. The large gap between the founding of New York province and the opening of its first college stands in contrast to institutions such as Harvard University, which was created only six years after the founding of Boston, Massachusetts, a colony with a more homogenous Puritan population.[2] Discussions regarding the founding of a college in the Province of New York began as early as 1704, when Colonel Lewis Morris wrote to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the missionary arm of the Church of England, persuading the society that New York City was an ideal community in which to establish a college.[3] In 1686[4] Governor of New York Thomas Dongan, 2nd Earl of Limerick unsuccessfully petitioned James II of England for a grant of the Duke's, known as King's Farm, to maintain his Jesuit College, which eventually failed.[5] Morris had initially designed the college to be built upon this land, which was vested to Trinity Church by Queen Anne and Lord Cornburry in 1705,[6] and nothing came of the proposition to form a college in the province until almost fifty years later.[7] The founding of Harvard in 1636 and Yale in 1701 had set no competitive juices flowing among New York's merchants. But the announcement in the summer of 1745 that New Jersey, which had only seven years before secured a government separate from New York's and was still considered by New Yorkers to be within its cultural catch basin, was about to found the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, demanded an immediate response.[8]

In 1746 an act was passed by the general assembly of New York to raise a sum of £2,250 by public lottery for the foundation of a new college, despite the fact that the University had neither a founding denomination nor a location for its first campus. In 1751, the assembly appointed a commission of ten New York residents, seven of whom were Church of England members, to direct the funds accrued by the state lottery towards the foundation of a college.[9] Funds were also provided by many of the wealthiest individuals of the period, including numerous slave owners and slave traders.[10] In March of the following year, the vestrymen of Trinity Church offered the commission the six-northernmost acres of its property for the foundation of the college, which settled the problem of the college's first campus; however, considerable outcry from William Livingston and other members of the commission who believed that the college should be nonsectarian caused further delay in the college's founding. Despite Livingston's objections, the commission voted to accept the lands from Trinity Church on the condition that the college's affiliation be Church of England.[11] The commission chose as the college's first president Dr. Samuel Johnson, a preeminent scholar who had received his doctorate from The University of Oxford, and had been sought in similar capacity to preside over the College of Philadelphia, now The University of Pennsylvania.[12]

King's College (1754–1784)

- Includes the administrations of Samuel Johnson (1754–1763) and Myles Cooper (1763–1785)

Classes were initially held in July 1754, the delay stemming from the inability of the college to secure adequate faculty. Dr. Johnson was the only instructor of the college's first class, which consisted of a mere eight students. Instruction was held in a new schoolhouse adjoining Trinity Church, located on what is now lower Broadway in Manhattan.[13] The college was officially founded on October 31, 1754, as King's College by royal charter of King George II, making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States.[1] On June 3 of the following year, the Governors of the College adopted a design prepared by Dr. Johnson for the seal of King's College, which continues to be that of Columbia College with the alteration in name.[14] In 1760, King's College moved to its own building at Park Place, near the present City Hall, and in 1767 it established the first American medical school to grant the M.D. degree.[1]

Controversy surrounded the founding of the new college in New York, as it was a thoroughly Church of England institution dominated by the influence of Crown officials in its governing body, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Fears of the establishment of a Church of England episcopacy and of Crown influence in America through King's College were underpinned by its vast wealth, far surpassing all other colonial colleges of the period.[15]

In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by Myles Cooper, a graduate of The Queen's College, Oxford, and an ardent Tory. In the political controversies which preceded The American Revolution, his chief opponent in discussions at the College was an undergraduate of the class of 1777, Alexander Hamilton. On one occasion, a mob came to the College, bent on doing violence to the president, but Hamilton held their attention with a speech, giving Cooper enough time to escape. The next year the Revolutionary War broke out and the College was turned into a military hospital and barracks.[13]

The American Revolution and the subsequent war were catastrophic for the operation of King's College. It suspended instruction for eight years beginning in 1776 with the arrival of the Continental Army in the spring of that year. The suspension continued through the military occupation of New York City by British troops until their departure in 1783. The college's library was looted and its sole building requisitioned for use as a military hospital first by American and then British forces.[17][18] Although the college had been considered a bastion of Tory sentiment,[19] it nevertheless produced many key leaders of the Revolutionary generation — individuals later instrumental in the college's revival. Among the earliest students and trustees of King's College were five "founding fathers" of the United States: John Jay, who negotiated the Treaty of Paris between the United States and the Kingdom of Great Britain, ending the Revolutionary War, and who later became the first Chief Justice of the United States; Alexander Hamilton, military aide to General George Washington, author of most of the Federalist Papers, and the first Secretary of the Treasury; Gouverneur Morris, the author of the final draft of the United States Constitution; Robert R. Livingston, a member of the Committee of Five, that drafted the Declaration of Independence; and Egbert Benson who represented New York in the Continental Congress and the Annapolis Convention, and who was a ratifier of the United States Constitution.[1]

Post Revolutionary War Recovery (1784–1800)

Columbia College under the Regents

King's college had been in a state of abeyance for eight years by the time the war ended, with many of the members of the college's Board of Governors either absent or killed during the revolution. The college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the schools charter the state might demand.[20] The Legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College."[21] The Act created a Board of Regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's, giving them the power to hire a college president and appoint professors, but prohibiting the College from administering any "religious test-oath" to its faculty. Finally, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the Legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College."[21]

On May 5, 1784, the Regents held their first meeting, instructing Treasurer Brockholst Livingston and Secretary Robert Harpur (who was Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at King's) to recover the books, records and any other assets that had been dispersed during the war, and appointing a committee to supervise the repairs of the college building. In addition, the Regents moved quickly to rebuild Columbia's faculty, appointing William Cochran instructor of Greek and Latin.[21] In the summer of 1784, after the legislature passed the act restoring the college, Major General James Clinton, a hero of the revolutionary war, brought his son DeWitt Clinton to New York on his way to enroll him as a student at the College of New Jersey. When James Duane, the Mayor of New York and a member of the Regents, heard that the younger Clinton was leaving the state for his education, he pleaded with Cochran to offer him admission to the reconstituted Columbia. Cochran agreed — partly because DeWitt's uncle, George Clinton, the Governor of New York, had recently been elected Chancellor of the College by the Regents — and DeWitt Clinton became one of nine students admitted to Columbia in the year 1784.[21]

During the period under the Regents, many efforts were made to put the University on respectable footing, resolving to organize the college into the four faculties of Arts, Divinity, Medicine, and Law. A number of different professorships were created within each faculty, while the college remained under the supervision of the Regents. The staff of the entire university - which included numerous aforementioned professors, a president, a secretary, and a librarian – operated under the yearly budget of £1,200.[22] During this period no president was able to be appointed due to the college's inadequate funds, which rendered it unable to offer a salary as would induce a suitable person to accept the office. Instead, the duties of the president's office were held by the schools various professors, which led to discord between the school's faculty members. The Regents finally became aware of the college's defective constitution in February 1787 and appointed a revision committee, which was headed by John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. In April of that same year, a new charter was adopted for the college, still in use today, granting power to a private board of twenty-four Trustees.[23]

Columbia College

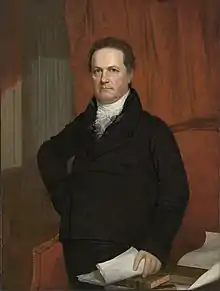

On May 21, 1787, William Samuel Johnson, the son of Dr. Samuel Johnson, was unanimously elected President of Columbia College. Prior to serving at the University, Johnson had participated in the First Continental Congress and been chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.[24] For a period in the 1790s, with New York City as the federal and state capital and the country under successive Federalist governments, a revived Columbia thrived under the auspices of Federalists such as Hamilton and Jay. Both President George Washington and Vice President John Adams attended the College's commencement on May 6, 1789, as a tribute of honor to the many alumni of the school that had been instrumental in bringing about the independence of the fledgling United States of America.[25]

During the period of Johnson's presidency, the College's campus began to expand, and in 1792 a new library extension was built to accommodate the College's growing library with the help of a grant from the Legislature of New York State. In December 1793, the Professorship of Law was filled by the election of James Kent, who gave the first instruction of law at any American University and was a forerunner to the University's Law School.[26] On July 16, 1800, the seventy-four-year-old Dr. Johnson resigned his presidency of the College.[27] In 1801, the Board of Trustees appointed Charles Henry Wharton as Dr. Johnson's successor. Wharton was to assume the office of president at the August commencement ceremonies, but he did not appear for them, and resigned in the fall.[28]

College stagnation (1800–1857)

Despite the College's liberal acceptance of various religious and ethnic groups, during the period from 1785–1849 the institutional life of the college was a continuous struggle for existence, owing to inadequate means and lack of financial support.[26][29]

The curriculum of the college during the beginning of the 19th century was mostly focused on study of the classics. As a result, the major prerequisite for admission into the College was familiarity with Greek and Latin and a basic understanding of mathematics. In 1810, following the advice of a committee put together by members of the school, the College greatly tightened its admission standards; nonetheless, admission of qualified students increased, with 135 students matriculating in 1810.[30] In the preceding decade, the average size of the graduating class had been seventeen.[31]

Because the school had no athletic program, student life during this period was mainly focused around literary groups such as the Philolexian Society, which was founded in 1802. In 1811, the College's new president William Harris presided over what became known as the ""Riotous Commencement" in which students violently protested the faculty's decision not to confer a degree upon John Stevenson, who had inserted objectionable words into his commencement speech.

The main building which housed the College was decayed and unsightly in appearance; however, the funds of the College were augmented somewhat by the growing importance of its investments in real estate, although the true value of some of these acquisitions would not come to light until over a century later. For example, in 1814 the New York Legislature responded to the College's appeal for financial assistance by giving the school the Elgin Botanic Garden, a twenty-acre tract of land that had been privately developed as the nation's first botanical garden by physician David Hosack, but which Hosack had closed and resold to the state at a loss.[32] The site, which had been 3+1⁄2 miles (5.6 km) outside of the city limits in 1801, was leased by Columbia to John D. Rockefeller Jr. in the 1920s for the construction of Rockefeller Center.[33][34] It was still owned by Columbia until 1985, when it was sold for $400 million.[35]

In November 1813, the College agreed to combine its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. During the 1820s, the College renovated its campus and continued to seek grants from the state while it slowly expanded the scope of its academic catalog, adding Italian courses in 1825.[36]

The College's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the remaining forty years, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the College functioned. Adding to the woes of the College during this period, in 1831 the school began to face direct competition in the form of the University of the City of New York, which was later to become New York University. This new university had a more utilitarian curriculum, which stood in contrast to Columbia's focus on ancient literature. As a demonstration of NYU's popularity, by the second year of its operation it had 158 students, whereas Columbia College, eighty years after its founding, only had 120. Trustees of Columbia attempted to block the founding of NYU, issuing pamphlets to dissuade the Legislature from opening another university while Columbia continued to struggle financially.[37] By July, 1854 the Christian Examiner of Boston, in an article entitled "The Recent Difficulties at Columbia College", noted that the school was "good in classics" yet "weak in sciences", and had "very few distinguished graduates".[38]

When Charles King became Columbia's president in November 1849, the College was in large amounts of debt, having exceeded their annual expenditure by about $2200 for the past fifteen years. On his formal inauguration, King spoke on the duties and responsibilities of the university staff, and espoused the virtues of copying the English university system.[39] By this time, the College's investments in New York real estate, particularly the Botanical Garden, became a primary source of steady income for the school, mainly owing to the city's rapidly increasing population.[40]

Expansion and Madison Avenue (1857–1896)

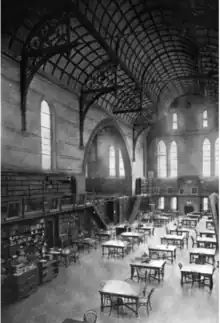

In 1857, the College moved from Park Place to a primarily Gothic Revival campus on 49th Street and Madison Avenue, at the former site of the New York Institute for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, where it remained for the next fifty years. While the new location was described as a "delightful one" with "a beautiful lawn slope from the college down to 49th street" it also was in a part of the city very much still under construction.[41] Most unfortunately, "the ends of rows of coffins filled with the bones of the unknown dead, are still to be seen protruding from the bank of earth left by the cutting through of the 4th Avenue"[42] along the east side of campus.

The transition to the new campus coincided with a new outlook for the college; during the 1857 commencement, College President Charles King proclaimed Columbia "a university". During the last half of the nineteenth century, under the leadership of President F.A.P. Barnard, the institution rapidly assumed the shape of a true modern university. Columbia Law School was founded in 1858, and in 1864 the School of Mines, the country's first such institution and the precursor to today's Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, was established. The Graduate Faculties in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science awarded its first PhD in 1875.[38][43] Barnard College for women, established by the eponymous Columbia president, was established in 1889; the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons came under the aegis of the University in 1891, followed by Teachers College, Columbia University in 1893.

Among the new buildings constructed in this location, were Hamilton Hall (1879) as well as buildings for the School of Mines (1880-1884) and a combined building for the Library and the Law School.[44]

This period also witnessed the inauguration of Columbia's participation in intercollegiate sports, with the creation of the baseball team in 1867, the organization of the football team in 1870, and the creation of a crew team by 1873. The first intercollegiate Columbia football game was a 6–3 loss to Rutgers. The Columbia Daily Spectator began publication during this period as well, in 1877.[45]

Morningside Heights (1896–Present)

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, university president Seth Low moved the campus again, from 49th Street to its present location, a more spacious (and, at the time, more rural) campus in the developing neighborhood of Morningside Heights. The site was formerly occupied by the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. One of the asylum's buildings, the warden's cottage (later known as East Hall and Buell Hall), still stands today.[46]

The building often depicted as emblematic of Columbia is the centerpiece of the Morningside Heights campus, Low Memorial Library. Constructed in 1895, the building is still referred to as "Low Library" although it has not functioned as a library since 1934. It currently houses the offices of the President, Provost, the Visitor's Center, and the Trustees' Room and Columbia Security. Patterned loosely on the Classical Pantheon, it is surmounted by the largest all-granite dome in the United States.[47]

Under the leadership of Low's successor, Nicholas Murray Butler, Columbia rapidly became the nation's major institution for research, setting the "multiversity" model that later universities would adopt. On the Morningside Heights campus, Columbia centralized on a single campus the College, the School of Law, the Graduate Faculties, the School of Mines (predecessor of the Engineering School), and the College of Physicians & Surgeons. Butler went on to serve as president of Columbia for over four decades and became a giant in American public life (as one-time vice presidential candidate and a Nobel Laureate). His introduction of "downtown" business practices in university administration led to innovations in internal reforms such as the centralization of academic affairs, the direct appointment of registrars, deans, provosts, and secretaries, as well as the formation of a professionalized university bureaucracy, unprecedented among American universities at the time.[1]

In 1893 the Columbia University Press was founded to "promote the study of economic, historical, literary, scientific and other subjects; and to promote and encourage the publication of literary works embodying original research in such subjects." Among its publications are The Columbia Encyclopedia, first published in 1935, and The Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World, first published in 1952. In 1902, New York newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer donated a substantial sum to the University for the founding of a school to teach journalism. The result was the 1912 opening of the Graduate School of Journalism—the only journalism school in the Ivy League. Columbia does not, however, offer an undergraduate degree in journalism. The school is the administrator of the Pulitzer Prize and the duPont-Columbia Award in broadcast journalism.[48][49]

In 1904 Columbia organized adult education classes into a formal program called Extension Teaching (later renamed University Extension). Courses in Extension Teaching eventually give rise to the Columbia Writing Program, the Columbia Business School, and the School of Dentistry.[50]

In 1928, Seth Low Junior College was established by Columbia University in order to mitigate the number of Jewish applicants to Columbia College.[51][52] The college was closed in 1938 due to the adverse effects of the Great Depression and its students were subsequently taught at Mornington Heights, although they did not belong to any college but to the university at large.[53]

There was an evening school called University Extension, which taught night classes, for a fee, to anyone willing to attend. In 1947, the program was reorganized as an undergraduate college and designated the School of General Studies in response to the return of GIs after World War II.[54] In 1995, the School of General Studies was again reorganized as a full-fledged liberal arts college for non-traditional students (those who have had an academic break of one year or more) and was fully integrated into Columbia's traditional undergraduate curriculum.[55] Within the same year, the Division of Special Programs—later the School of Continuing Education, and now the School of Professional Studies—was established to reprise the former role of University Extension.[56] While the School of Professional Studies only offered non-degree programs for lifelong learners and high school students in its earliest stages, it now offers degree programs in a diverse range of professional and inter-disciplinary fields.[57]

By the late 1930s, a Columbia student could study with the likes of Jacques Barzun, Paul Lazarsfeld, Mark Van Doren, Lionel Trilling, and I. I. Rabi. The University's graduates during this time were equally accomplished—for example, two alumni of Columbia's Law School, Charles Evans Hughes and Harlan Fiske Stone (who also held the position of Law School dean), served successively as Chief Justices of the United States. Dwight Eisenhower served as Columbia's president from 1948 until he became the President of the United States in 1953.[58][59][60]

Research into the atom by faculty members John R. Dunning, I. I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi and Polykarp Kusch placed Columbia's Physics Department in the international spotlight in the 1940s after the first nuclear pile was built to start what became the Manhattan Project.[61] Following the end of World War II, the School of International Affairs was founded in 1946, beginning by offering the Master of International Affairs. To satisfy an increasing desire for skilled public service professionals at home and abroad, the School added the Master of Public Administration degree in 1977. In 1981, the School was renamed the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA). The School introduced an MPA in Environmental Science and Policy in 2001 and, in 2004, SIPA inaugurated its first doctoral program — the interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Sustainable Development.[62]

During World War II, Columbia, Morningside Heights campus, was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[63]

During the 1960s Columbia experienced large-scale student activism centering over the Vietnam War and the demand for greater student rights. Many students, led by the Students for a Democratic Society and its President Mark Rudd protested the University's ties with the defense establishment and its controversial plans to build a gym in Morningside Park. The fervor on campus reached a climax in the spring of 1968 when hundreds of students occupied various buildings on campus. The incident forced the resignation of Columbia's then President, Grayson Kirk and the establishment of the University Senate.[64][65]

Columbia College first admitted women in the fall of 1983, after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard College, an all female institution affiliated with the University, to merge the two schools. Barnard College still remains affiliated with Columbia, and all Barnard graduates are issued diplomas authorized by both Columbia University and Barnard College.[66]

During the late 20th century, the University underwent significant academic, structural, and administrative changes as it developed into a major research university. For much of the 19th century, the University consisted of decentralized and separate faculties specializing in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science. In 1979, these faculties were merged into the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.[67] In 1991, the faculties of Columbia College, the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of the Arts, and the School of Professional Studies were merged into the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, leading to the academic integration and centralized governance of these schools. In 2010, the School of International and Public Affairs, which was previously a part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, became an independent faculty.[68]

In 1997, the Columbia Engineering School was renamed the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, in honor of Chinese businessman Z. Y. Fu, who gave Columbia $26 million. The school is popularly referred to as "SEAS" or simply "the engineering school."[69]

See also

- Columbia College of Columbia University, the oldest liberal arts undergraduate college at Columbia University, New York

- Columbia Daily Spectator, a student newspaper at Columbia University, New York

- Columbia Journal, the graduate writing program's student-founded, student-run literary journal Columbia University School of the Arts

- Columbia Journalism Review, a bimonthly journal published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

- Columbia Law School

- Columbia Business Law Review, a monthly journal published by students at Columbia Law School

- The Pulitzer Prize

- The School at Columbia University, New York City

- Teachers College, Columbia University's Graduate School of Education

References

Citations

- "A Brief History of Columbia". Columbia University. 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- Moore 1846, pp. 6–7.

- McCaughey 2003, p. 1.

- Schwickerath, Robert (1903). Jesuit Education: Its History and Principles Viewed in the Light of Modern Education Problems. p. 202.

- Phelan, Thomas P. (December 1911). "Thomas Dongan, Catholic Colonial Governor of New York". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 22 (4): 207–237. JSTOR 44208940.

- Brown, P. W. (September 1934). "Thomas Dongan: Soldier and Statesman: Irish-Catholic Governor of New York 1683-1688". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 23 (91): 489–501. JSTOR 30079857.

- Matthews 1904, pp. 8–10.

- McCaughey 2003, p. 8.

- Keppel, Fredrick Paul (1914). Columbia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 26.

- "2. Where the Money Came From". Columbia University and Slavery. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

Merchants, including "the wealthiest and most important men of their time" considerably outnumbered lawyers, ministers, and others on the board of governors. They donated generously to the College. The initial list of 66 "subscribers," who donated a total of over 5,000 pounds to help launch King's, included Atlantic slave traders John Watts, Nathaniel Marston, Adoniah Schuyler, and John Cruger, and many others engaged in commerce with the Caribbean. Apart from Governor Charles Hardy, who gave 500 pounds, the largest contribution, 200, came from Marston, one of the city's merchants most actively involved in the slave trade from Africa. Most of the donors had a connection to slavery either via ownership or trade.

- Humphrey, David C. (1976). From King's College to Columbia. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 35–40. ISBN 0-231-03942-5.

- Matthews 1904, p. 2.

- Butler 1912, p. 3.

- Matthews 1904, p. 19.

- McCaughey, Robert A. (September 15, 2004). "Farewell, Aristocracy – The World Turned Upside Down". Social History of Columbia University Fall 2004 Lectures. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-59420-009-0.

- Schecter, Barnet (2002). The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution. Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1374-2.

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2671-4.

- Matthews 1904, p. 18.

- Matthews 1904, p. 59.

- A History of Columbia University, 1754–1904. New York: Macmillan. 1904. ISBN 1-4021-3737-0.

- Matthews 1904, pp. 60–64.

- Moore 1846, pp. 65–70.

- Groce, C. G. (1937). William Samuel Johnson: A Maker of the Constitution. New York, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Matthews 1904, p. 74.

- Butler 1912, p. 5.

- Moore 1846, p. 75.

- McCaughey 2003, p. 65.

- McCaughey 2003, p. 86.

- Moore 1846, pp. 50–53.

- Matthews 1904, pp. 86–96.

- Okrent 2003, p. 21.

- Okrent 2003, p. 106.

- Matthews 1904, pp. 90–100.

- Dowd, Maureen (February 6, 1985). "Columbia Is to Get $400 Million in Rockefeller Center Land Sale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Moore 1846, pp. 53–60.

- McCaughey 2003, pp. 87–89.

- McCaughey 2003, Appendix E: Institutional Comparisons.

- Columbia University, Addresses at the Inauguration of Mr. Charles King (1848), Ch. 4, pp. 3–53

- Butler 1912, pp. 5–8.

- Dolkart, Andrew S. (2001-03-15). Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07851-1.

- Dolkart, Andrew S. (2001-03-15). Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07851-1.

- McCaughey 2003, Leading American University Producers of PhDs, 1861–1900.

- Dolkart, Andrew S. (2001-03-15). Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07851-1.

- "Columbia College Student Life Timeline". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ""Columbia University's Lunatic Past." Ephemeral New York website. May 5, 2008". 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- "Low Memorial Library". 2002-07-30. Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- "About the School". Columbia University School of Journalism. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- Andie Tucher. "Joseph Pulitzer's Mission". Columbia University School of Journalism. Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- "About Columbia Business School". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2011-03-10. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- McCaughey 2003, p. 271.

- "Columbia Daily Spectator 3 April 1928 — Columbia Spectator". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Asimov, I. (1979) In Memory Yet Green, Avon Books, pp. 157, 159–160, 240

- "School of General Studies: History". Columbia School of General Studies. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- "What makes GS different from Columbia's traditional undergraduate colleges? | General Studies". Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- "University Senate". Archived from the original on 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- "The School Our History | Columbia University School of Professional Studies". Sps.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- Ross, William G (2007). The Chief Justiceship of Charles Evans Hughes. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-679-8.

- "Attorney General Biographies: Harlan Fiske Stone". United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 2011-02-11. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- "Biography: Dwight David Eisenhower". Eisenhower Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-05-23. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- Broad, William J. (2007-10-30). "Why They Called It the Manhattan Project". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- "About SIPA: Growth and Tradition". Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-04-19. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- "World War II Wartime Efforts". New York City: Columbia University. 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- Kurlansky, Mark (2005). 1968: The Year That Rocked The World. New York, New York: Random House. pp. 194–199. ISBN 0-345-45582-7.

- Bradley, Stefan (2009). Harlem vs. Columbia University: Black Student Power in the Late 1960s. New York, New York: University of Illinois. pp. 5–19, 164–191. ISBN 978-0-252-03452-7.

- Link text. Archived 2010-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "GSAS at a Glance | Columbia University | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences". Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- "History of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences | Faculty of Arts and Sciences". Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- "History: A Forward Looking Tradition". The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

Sources

- Butler, Nicholas Murray (1912). An Official Guide to Columbia University. New York, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Matthews, Brander; John Pine; Harry Peck; Munroe Smith (1904). A History of Columbia University: 1754–1904. London, England: Macmillan Company.

- McCaughey, Robert (2003). Stand, Columbia : A History of Columbia University in the City of New York. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13008-2.

- Moore, Nathanal Fischer (1846). A Historical Sketch of Columbia. New York, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Okrent, Daniel (2003). Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center. London: Penguin Book. ISBN 978-0-142-00177-6.