History of education

The history of education extends at least as far back as the first written records recovered from ancient civilizations. Historical studies have included virtually every nation.[1][2][3]

Education in ancient civilization

North Africa and Middle East

Perhaps the earliest formal school was developed in Egypt's Middle Kingdom under the direction of Kheti, treasurer to Mentuhotep II (2061-2010 BC).[4]

In Mesopotamia, the early logographic system of cuneiform script took many years to master. Thus only a limited number of individuals were hired as scribes to be trained in its reading and writing. Only royal offspring and sons of the rich and professionals such as scribes, physicians, and temple administrators, were schooled.[5] Most boys were taught their father's trade or were apprenticed to learn a trade.[6] Girls stayed at home with their mothers to learn housekeeping and cooking, and to look after the younger children. Later, when a syllabic script became more widespread, more of the Mesopotamian population became literate. Later still in Babylonian times there were libraries in most towns and temples; an old Sumerian proverb averred "he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn." There arose a whole social class of scribes, mostly employed in agriculture, but some as personal secretaries or lawyers.[7] Women as well as men learned to read and write, and for the Semitic Babylonians, this involved knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, and a complicated and extensive syllabary. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools known as edubas (2000–1600 BCE), through which literacy was disseminated. The Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem from Ancient Mesopotamia is among the earliest known works of literary fiction. The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic date from as early as the Third Dynasty of Ur (2150–2000 BC) (Dalley 1989: 41–42).

Ashurbanipal (685 – c. 627 BC), a king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, was proud of his scribal education. His youthful scholarly pursuits included oil divination, mathematics, reading and writing as well as the usual horsemanship, hunting, chariotry, soldierliness, craftsmanship, and royal decorum. During his reign he collected cuneiform texts from all over Mesopotamia, and especially Babylonia, in the library in Nineveh, the first systematically organized library in the ancient Middle East,[8] which survives in part today.

In ancient Egypt, literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes' status. Literacy remains an elusive subject for ancient Egypt.[9][10]Estimations of literacy range from 1 to 5 per cent of the population, based on very limited evidence[11][12][13][14] to much higher numbers.[15][16] Generalisations for the whole country, even at a given period, inevitably mask differences between regions, and, most importantly, between urban and rural populations. They may seriously underestimate the proportion of the population able to read and write in towns; low literacy estimates are a regular feature of 19th and 20th century attitudes to ancient and medieval (pre-Reformation) societies.[17]

In ancient Israel, the Torah (the fundamental religious text) includes commands to read, learn, teach and write the Torah, thus requiring literacy and study. In 64 AD the high priest caused schools to be opened.[18] Emphasis was placed on developing good memory skills in addition to comprehension oral repetition. For details of the subjects taught, see History of education in ancient Israel and Judah. Although girls were not provided with formal education in the yeshivah, they were required to know a large part of the subject areas to prepare them to maintain the home after marriage, and to educate the children before the age of seven. Despite this schooling system, it would seem that many children did not learn to read and write, because it has been estimated that "at least ninety percent of the Jewish population of Roman Palestine [in the first centuries AD] could merely write their own name or not write and read at all",[19] or that the literacy rate was about 3 per cent.[20]

In the Islamic civilization that spread all the way between China and Spain during the time between the 7th and 19th centuries, Muslims started schooling from 622 in Medina, which is now a city in Saudi Arabia, schooling at first was in the mosques (masjid in Arabic) but then schools became separate in schools next to mosques. The first separate school was the Nizamiyah school. It was built in 1066 in Baghdad. Children started school from the age of six with free tuition. The Quran encourages Muslims to be educated. Thus, education and schooling sprang up in the ancient Muslim societies. Moreover, Muslims had one of the first universities in history which is Al-Qarawiyin University in Fez, Morocco. It was originally a mosque that was built in 859.[21]

India

In ancient India, education was mainly imparted through the Vedic and Buddhist education system. Sanskrit was the language used to impart the Vedic education system. Pali was the language used in the Buddhist education system. In the Vedic system, a child started his education at the age of 8 to 12, whereas in the Buddhist system the child started his education at the age of eight. The main aim of education in ancient India was to develop a person's character, master the art of self-control, bring about social awareness, and to conserve and take forward ancient culture.

The Buddhist and Vedic systems had different subjects. In the Vedic system of study, the students were taught the four Vedas – Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda and Atharva Veda, they were also taught the six Vedangas – ritualistic knowledge, metrics, exegetics, grammar, phonetics and astronomy, the Upanishads and more.

Vedic Education

In ancient India, education was imparted and passed on orally rather than in written form. Education was a process that involved three steps, first was Shravana (hearing) which is the acquisition of knowledge by listening to the Shrutis. The second is Manana (reflection) wherein the students think, analyze and make inferences. Third, is Nididhyāsana in which the students apply the knowledge in their real life.

During the Vedic period from about 1500 BC to 600 BC, most education was based on the Veda (hymns, formulas, and incantations, recited or chanted by priests of a pre-Hindu tradition) and later Hindu texts and scriptures. The main aim of education, according to the Vedas, is liberation.

Vedic education included proper pronunciation and recitation of the Veda, the rules of sacrifice, grammar and derivation, composition, versification and meter, understanding of secrets of nature, reasoning including logic, the sciences, and the skills necessary for an occupation.[22] Some medical knowledge existed and was taught. There is mention in the Veda of herbal medicines for various conditions or diseases, including fever, cough, baldness, snake bite and others.[22]

Education included teaching of Ayurveda, 64 kalas (arts), crafts, Shilpa Shastra, Natya Shastra.[22][23]

Educating the women was given a great deal of importance in ancient India. Women were trained in dance, music and housekeeping. The Sadyodwahas class of women got educated till they were married. The Brahmavadinis class of women never got married and educated themselves for their entire life. Parts of Vedas that included poems and religious songs required for rituals were taught to women. Some noteworthy women scholars of ancient India include Ghosha, Gargi, Indrani and so on.[24]

The oldest of the Upanishads – another part of Hindu scriptures – date from around 500 BC. The Upanishads are considered as "wisdom teachings" as they explore the deeper and actual meaning of sacrifice. These texts encouraged an exploratory learning process where teachers and students were co-travellers in a search for truth. The teaching methods used reasoning and questioning. Nothing was labelled as the final answer.[22]

The Gurukula system of education supported traditional Hindu residential schools of learning; typically the teacher's house or a monastery. In the Gurukul system, the teacher (Guru) and the student (Śiṣya) were considered to be equal even if they belonged to different social standings. Education was free, but students from well-to-do families paid "Gurudakshina", a voluntary contribution after the completion of their studies. Gurudakshina is a mark of respect by the students towards their Guru. It is a way in which the students acknowledged, thanked and respected their Guru, whom they consider to be their spiritual guide. At the Gurukulas, the teacher imparted knowledge of Religion, Scriptures, Philosophy, Literature, Warfare, Statecraft, Medicine, Astrology and History. The corpus of Sanskrit literature encompasses a rich tradition of poetry and drama as well as technical scientific, philosophical and generally Hindu religious texts, though many central texts of Buddhism and Jainism have also been composed in Sanskrit.

Two epic poems formed part of ancient Indian education. The Mahabharata, part of which may date back to the 8th century BC,[25] discusses human goals (purpose, pleasure, duty, and liberation), attempting to explain the relationship of the individual to society and the world (the nature of the 'Self') and the workings of karma. The other epic poem, Ramayana, is shorter, although it has 24,000 verses. It is thought to have been compiled between about 400 BC and 200 AD. The epic explores themes of human existence and the concept of dharma (doing ones duty).[25]

Buddhist Education

In the Buddhist education system, the subjects included Pitakas.

Vinaya Pitaka

It is a Buddhist canon that contains a code of rules and regulations that govern the Buddhist community residing in the Monastery. The Vinaya Pitaka is especially preached to Buddhist monks (Sanga) to maintain discipline when interacting with people and nature. The set of rules ensures that people, animals, nature and the environment are not harmed by the Buddhist monks.

Sutta Pitaka

It is divided into 5 niyakas (collections). It contains Buddhas teachings recorded mainly as sermons and.

Abhidhamma Pitaka

It contains a summary and analysis of Buddha's teachings.

An early centre of learning in India dating back to the 5th century BC was Taxila (also known as Takshashila), which taught the trayi Vedas and the eighteen accomplishments.[26] It was an important Vedic/Hindu[27] and Buddhist[28] centre of learning from the 6th century BC[29] to the 5th century AD.[30][31]

Another important centre of learning from 5th century CE was Nalanda. In the kingdom of Magadha, Nalanda was well known Buddhist monastery. Scholars and students from Tibet, China, Korea and Central Asia traveled to Nalanda in pursuit of education. Vikramashila was one of the largest Buddhist monasteries that was set up in 8th to 9th centuries.

China

According to legendary accounts, the rulers Yao and Shun (ca. 24th–23rd century BC) established the first schools. The first education system was created in Xia dynasty (2076–1600 BC). During Xia dynasty, government built schools to educate aristocrats about rituals, literature and archery (important for ancient Chinese aristocrats).

During Shang dynasty (1600 BC to 1046 BC), normal people (farmers, workers etc.) accepted rough education. In that time, aristocrats' children studied in government schools. And normal people studied in private schools. Government schools were always built in cities and private schools were built in rural areas. Government schools paid attention on educating students about rituals, literature, politics, music, arts and archery. Private schools educated students to do farmwork and handworks.[32]

During the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BC), there were five national schools in the capital city, Pi Yong (an imperial school, located in a central location) and four other schools for the aristocrats and nobility, including Shang Xiang. The schools mainly taught the Six Arts: rites, music, archery, charioteering, calligraphy, and mathematics. According to the Book of Rites, at age twelve, boys learned arts related to ritual (i.e. music and dance) and when older, archery and chariot driving. Girls learned ritual, correct deportment, silk production and weaving.[33]

It was during the Zhou dynasty that the origins of native Chinese philosophy also developed. Confucius (551–479 BC) founder of Confucianism, was a Chinese philosopher who made a great impact on later generations of Chinese, and on the curriculum of the Chinese educational system for much of the following 2000 years.

Later, during the Qin dynasty (246–207 BC), a hierarchy of officials was set up to provide central control over the outlying areas of the empire. To enter this hierarchy, both literacy and knowledge of the increasing body of philosophy was required: "....the content of the educational process was designed not to engender functionally specific skills but rather to produce morally enlightened and cultivated generalists".[34]

During the Han dynasty (206–221 AD), boys were thought ready at age seven to start learning basic skills in reading, writing and calculation.[32] In 124 BC, the Emperor Wudi established the Imperial Academy, the curriculum of which was the Five Classics of Confucius. By the end of the Han dynasty (220 AD) the academy enrolled more than 30,000 students, boys between the ages of fourteen and seventeen years. However education through this period was a luxury.[33]

The nine-rank system was a civil service nomination system during the Three Kingdoms (220–280 AD) and the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589 AD) in China. Theoretically, local government authorities were given the task of selecting talented candidates, then categorizing them into nine grades depending on their abilities. In practice, however, only the rich and powerful would be selected. The Nine Rank System was eventually superseded by the imperial examination system for the civil service in the Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

Greece and Rome

In the city-states of ancient Greece, most education was private, except in Sparta. For example, in Athens, during the 5th and 4th century BC, aside from two years military training, the state played little part in schooling.[35][36] Anyone could open a school and decide the curriculum. Parents could choose a school offering the subjects they wanted their children to learn, at a monthly fee they could afford.[35] Most parents, even the poor, sent their sons to schools for at least a few years, and if they could afford it from around the age of seven until fourteen, learning gymnastics (including athletics, sport and wrestling), music (including poetry, drama and history) and literacy.[35][36] Girls rarely received formal education. At writing school, the youngest students learned the alphabet by song, then later by copying the shapes of letters with a stylus on a waxed wooden tablet. After some schooling, the sons of poor or middle-class families often learnt a trade by apprenticeship, whether with their father or another tradesman.[35] By around 350 BC, it was common for children at schools in Athens to also study various arts such as drawing, painting, and sculpture. The richest students continued their education by studying with sophists, from whom they could learn subjects such as rhetoric, mathematics, geography, natural history, politics, and logic.[35][36] Some of Athens' greatest schools of higher education included the Lyceum (the so-called Peripatetic school founded by Aristotle of Stageira) and the Platonic Academy (founded by Plato of Athens). The education system of the wealthy ancient Greeks is also called Paideia. In the subsequent Roman empire, Greek was the primary language of science. Advanced scientific research and teaching was mainly carried on in the Hellenistic side of the Roman empire, in Greek.

The education system in the Greek city-state of Sparta was entirely different, designed to create warriors with complete obedience, courage, and physical perfection. At the age of seven, boys were taken away from their homes to live in school dormitories or military barracks. There they were taught sports, endurance and fighting, and little else, with harsh discipline. Most of the population was illiterate.[35][36]

The first schools in Ancient Rome arose by the middle of the 4th century BC.[37] These schools were concerned with the basic socialization and rudimentary education of young Roman children. The literacy rate in the 3rd century BC has been estimated as around one per cent to two per cent.[38] There are very few primary sources or accounts of Roman educational process until the 2nd century BC,[37] during which there was a proliferation of private schools in Rome.[38] At the height of the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire, the Roman educational system gradually found its final form. Formal schools were established, which served paying students (very little in the way of free public education as we know it can be found).[39] Normally, both boys and girls were educated, though not necessarily together.[39] In a system much like the one that predominates in the modern world, the Roman education system that developed arranged schools in tiers. The educator Quintilian recognized the importance of starting education as early as possible, noting that "memory … not only exists even in small children, but is specially retentive at that age".[40] A Roman student would progress through schools just as a student today might go from elementary school to middle school, then to high school, and finally college. Progression depended more on ability than age[39] with great emphasis being placed upon a student's ingenium or inborn "gift" for learning,[41] and a more tacit emphasis on a student's ability to afford high-level education. Only the Roman elite would expect a complete formal education. A tradesman or farmer would expect to pick up most of his vocational skills on the job. Higher education in Rome was more of a status symbol than a practical concern.

Literacy rates in the Greco-Roman world were seldom more than 20 per cent; averaging perhaps not much above 10 per cent in the Roman empire, though with wide regional variations, probably never rising above 5 per cent in the western provinces. The literate in classical Greece did not much exceed 5 per cent of the population.[42][43]

Formal education in the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD)

Europe

The word school applies to a variety of educational organizations in the Middle Ages, including town, church, and monastery schools. During the late medieval period, students attending town schools were usually between the ages of seven and fourteen. Instruction for boys in such schools ranged from the basics of literacy (alphabet, syllables, simple prayers and proverbs) to more advanced instruction in the Latin language. Occasionally, these schools may also have taught rudimentary arithmetic or letter writing and other skills useful in business. Often instruction at various levels took place in the same schoolroom.[44]

During the Early Middle Ages, the monasteries of the Roman Catholic Church were the centers of education and literacy, preserving the Church's selection from Latin learning and maintaining the art of writing. Prior to their formal establishment, many medieval universities were run for hundreds of years as Christian monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), in which monks taught classes, and later as cathedral schools; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the early 6th century.[45]

The first medieval institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of arts, law, medicine, and theology.[1] These universities evolved from much older Christian cathedral schools and monastic schools, and it is difficult to define the date on which they became true universities, although the lists of studia generalia for higher education in Europe held by the Vatican are a useful guide.

Students in the twelfth-century were very proud of the master whom they studied under. They were not very concerned with telling others the place or region where they received their education. Even now when scholars cite schools with distinctive doctrines, they use group names to describe the school rather than its geographical location. Those who studied under Robert of Melun were called the Meludinenses. These people did not study in Melun, but in Paris, and were given the group name of their master. Citizens in the twelfth-century became very interested in learning the rare and difficult skills masters could provide.[46]

Ireland became known as the island of saints and scholars. Monasteries were built all over Ireland, and these became centres of great learning (see Celtic Church).

Northumbria was famed as a centre of religious learning and arts. Initially the kingdom was evangelized by monks from the Celtic Church, which led to a flowering of monastic life, and Northumbria played an important role in the formation of Insular art, a unique style combining Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, Byzantine and other elements. After the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD, Roman church practices officially replaced the Celtic ones but the influence of the Anglo-Celtic style continued, the most famous examples of this being the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) in a Northumbrian monastery, and much of it focuses on the kingdom.[47]

During the reign of Charlemagne, King of the Franks from 768 to 814 AD, whose empire united most of Western Europe for the first time since the Romans, there was a flowering of literature, art, and architecture known as the Carolingian Renaissance. Brought into contact with the culture and learning of other countries through his vast conquests, Charlemagne greatly increased the provision of monastic schools and scriptoria (centres for book-copying) in Francia. Most of the surviving works of classical Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in scholarship, promoting the liberal arts at the court, ordering that his children and grandchildren be well-educated, and even studying himself under the tutelage of Paul the Deacon, from whom he learned grammar, Alcuin, with whom he studied rhetoric, dialect and astronomy (he was particularly interested in the movements of the stars), and Einhard, who assisted him in his studies of arithmetic. The English monk Alcuin was invited to Charlemagne's court at Aachen, and brought with him the precise classical Latin education that was available in the monasteries of Northumbria.[48] The return of this Latin proficiency to the kingdom of the Franks is regarded as an important step in the development of mediaeval Latin. Charlemagne's chancery made use of a type of script currently known as Carolingian minuscule, providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. After the decline of the Carolingian dynasty, the rise of the Saxon Dynasty in Germany was accompanied by the Ottonian Renaissance.

Additionally, Charlemagne attempted to establish a free elementary education by parish priests for youth in a capitulary of 797. The capitulary states "that the priests establish schools in every town and village, and if any of the faithful wish to entrust their children to them to learn letters, that they refuse not to accept them but with all charity teach them ... and let them exact no price from the children for their teaching nor receive anything from them save what parents may offer voluntarily and from affection" (P.L., CV., col. 196)[49]

Cathedral schools and monasteries remained important throughout the Middle Ages; at the Third Lateran Council of 1179 the Church mandated that priests provide the opportunity of a free education to their flocks, and the 12th and 13th century renascence known as the Scholastic Movement was spread through the monasteries. These however ceased to be the sole sources of education in the 11th century when universities, which grew out of the monasticism began to be established in major European cities. Literacy became available to a wider class of people, and there were major advances in art, sculpture, music and architecture.[50]

In 1120, Dunfermline Abbey in Scotland by order of Malcolm Canmore and his Queen, Margaret, built and established the first high school in the UK, Dunfermline High School. This highlighted the monastery influence and developments made for education, from the ancient capital of Scotland.

Sculpture, paintings and stained glass windows were vital educational media through which Biblical themes and the lives of the saints were taught to illiterate viewers.[51]

Islamic world

The University of al-Qarawiyyin located in Fes, Morocco is the oldest existing, continually operating and the first degree awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records[52] and is sometimes referred to as the oldest university.[53]

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was a library, translation and educational centre from the 9th to 13th centuries. Works on astrology, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, and philosophy were translated. Drawing on Persian, Indian and Greek texts—including those of Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Euclid, Plotinus, Galen, Sushruta, Charaka, Aryabhata and Brahmagupta—the scholars accumulated a great collection of knowledge in the world, and built on it through their own discoveries. The House was an unrivalled centre for the study of humanities and for sciences, including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, zoology and geography. Baghdad was known as the world's richest city and centre for intellectual development of the time, and had a population of over a million, the largest in its time.[54]

The Islamic mosque school (Madrasah) taught the Quran in Arabic and did not at all resemble the medieval European universities.[55][56]

In the 9th century, Bimaristan medical schools were formed in the medieval Islamic world, where medical diplomas were issued to students of Islamic medicine who were qualified to be a practicing Doctor of Medicine.[57] Al-Azhar University, founded in Cairo, Egypt in 975, was a Jami'ah ("university" in Arabic) which offered a variety of post-graduate degrees, had a Madrasah and theological seminary, and taught Islamic law, Islamic jurisprudence, Arabic grammar, Islamic astronomy, early Islamic philosophy and logic in Islamic philosophy.[57]

Under the Ottoman Empire, the towns of Bursa and Edirne became major centers of learning.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the town of Timbuktu in the West African nation of Mali became an Islamic centre of learning with students coming from as far away as the Middle East. The town was home to the prestigious Sankore University and other madrasas. The primary focus of these schools was the teaching of the Qur'an, although broader instruction in fields such as logic, astronomy, and history also took place. Over time, there was a great accumulation of manuscripts in the area and an estimated 100,000 or more manuscripts, some of them dated from pre-Islamic times and 12th century, are kept by the great families from the town.[58] Their contents are didactic, especially in the subjects of astronomy, music, and botany. More than 18,000 manuscripts have been collected by the Ahmed Baba centre.[59]

China

Although there are more than 40,000 Chinese characters in written Chinese, many are rarely used. Studies have shown that full literacy in the Chinese language requires a knowledge of only between three and four thousand characters.[60]

In China, three oral texts were used to teach children by rote memorization the written characters of their language and the basics of Confucian thought.

The Thousand Character Classic, a Chinese poem originating in the 6th century, was used for more than a millennium as a primer for teaching Chinese characters to children. The poem is composed of 250 phrases of four characters each, thus containing exactly one thousand unique characters, and was sung in the same way that children learning the Latin alphabet may use the "alphabet song".

Later, children also learn the Hundred Family Surnames, a rhyming poem in lines of eight characters composed in the early Song dynasty[61] (i.e. in about the 11th century) which actually listed more than four hundred of the common surnames in ancient China.

From around the 13th century until the latter part of the 19th century, the Three Character Classic, which is an embodiment of Confucian thought suitable for teaching to young children, served as a child's first formal education at home. The text is written in triplets of characters for easy memorization. With illiteracy common for most people at the time, the oral tradition of reciting the classic ensured its popularity and survival through the centuries. With the short and simple text arranged in three-character verses, children learned many common characters, grammar structures, elements of Chinese history and the basis of Confucian morality.

After learning Chinese characters, students wishing to ascend in the social hierarchy needed to study the Chinese classic texts.

The early Chinese state depended upon literate, educated officials for operation of the empire. In 605 AD, during the Sui dynasty, for the first time, an examination system was explicitly instituted for a category of local talents. The merit-based imperial examination system for evaluating and selecting officials gave rise to schools that taught the Chinese classic texts and continued in use for 1,300 years, until the end the Qing dynasty, being abolished in 1911 in favour of Western education methods. The core of the curriculum for the imperial civil service examinations from the mid-12th century onwards was the Four Books, representing a foundational introduction to Confucianism.

Theoretically, any male adult in China, regardless of his wealth or social status, could become a high-ranking government official by passing the imperial examination, although under some dynasties members of the merchant class were excluded. In reality, since the process of studying for the examination tended to be time-consuming and costly (if tutors were hired), most of the candidates came from the numerically small but relatively wealthy land-owning gentry. However, there are vast numbers of examples in Chinese history in which individuals moved from a low social status to political prominence through success in imperial examination. Under some dynasties the imperial examinations were abolished and official posts were simply sold, which increased corruption and reduced morale.

In the period preceding 1040–1050 AD, prefectural schools had been neglected by the state and left to the devices of wealthy patrons who provided private finances.[62] The chancellor of China at that time, Fan Zhongyan, issued an edict that would have used a combination of government funding and private financing to restore and rebuild all prefectural schools that had fallen into disuse and abandoned.[62] He also attempted to restore all county-level schools in the same manner, but did not designate where funds for the effort would be formally acquired and the decree was not taken seriously until a later period.[62] Fan's trend of government funding for education set in motion the movement of public schools that eclipsed private academies, which would not be officially reversed until the mid-13th century.[62]

India

The first millennium and the few centuries preceding it saw the flourishing of higher education at Nalanda, Takshashila University, Ujjain, & Vikramshila Universities. Among the subjects taught were Art, Architecture, Painting, Logic, mathematics, Grammar, Philosophy, Astronomy, Literature, Buddhism, Hinduism, Arthashastra (Economics & Politics), Law, and Medicine. Each university specialized in a particular field of study. Takshila specialized in the study of medicine, while Ujjain laid emphasis on astronomy. Nalanda, being the biggest centre, handled all branches of knowledge, and housed up to 10,000 students at its peak.[63]

Mahavihara, another important center of Buddhist learning in India, was established by King Dharmapala (783 to 820) in response to a supposed decline in the quality of scholarship at Nālandā.[64]

Major work in the fields of Mathematics, Astronomy, and Physics were done by Aryabhata. Approximations of pi, basic trigonometric equation, indeterminate equation, and positional notation are mentioned in Aryabhatiya, his magnum opus and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician in Mathematics.[65] The work was translated into Arabic around 820CE by Al-Khwarizmi.

Hindu education

Even during the middle ages, education in India was imparted orally. Education was provided to the individuals free of cost. It was considered holy and honorable to do so. The ruling king did not provide any funds for education but it was the people belonging to the Hindu religion who donated for the preservation of the Hindu education. The centres of Hindu learning, which were the universities, were set up in places where the scholars resided. These places also became places of pilgrimage. So, more and more pilgrims funded these institutions.[66]

Islamic education

After Muslims started ruling India, there was a rise in the spread of Islamic education. The main aim of Islamic education included the acquisition of knowledge, propagation of Islam and Islamic social morals, preservation and spread of Muslim culture etc. Educations was mainly imparted through Maqtabs, Madrassahas and Mosques. Their education was usually funded by the noble or the landlords. The education was imparted orally and the children learnt a few verses from the Quran by rote.[67]

Indigenous education was widespread in India in the 18th century, with a school for every temple, mosque or village in most regions of the country.[68] The subjects taught included Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Theology, Law, Astronomy, Metaphysics, Ethics, Medical Science and Religion. The schools were attended by students representative of all classes of society.[69]

Japan

The history of education in Japan dates back at least to the 6th century, when Chinese learning was introduced at the Yamato court. Foreign civilizations have often provided new ideas for the development of Japan's own culture.

Chinese teachings and ideas flowed into Japan from the sixth to the 9th century. Along with the introduction of Buddhism came the Chinese system of writing and its literary tradition, and Confucianism.

By the 9th century, Heian-kyō (today's Kyoto), the imperial capital, had five institutions of higher learning, and during the remainder of the Heian period, other schools were established by the nobility and the imperial court. During the medieval period (1185–1600), Zen Buddhist monasteries were especially important centers of learning, and the Ashikaga School, Ashikaga Gakko, flourished in the 15th century as a center of higher learning.

Aztec

Aztec is a term used to refer to certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who achieved political and military dominance over large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the Late post-Classic period in chronology.

Until the age of fourteen, the education of children was in the hands of their parents, but supervised by the authorities of their calpōlli. Part of this education involved learning a collection of sayings, called huēhuetlàtolli ("sayings of the old"), that embodied the Aztecs' ideals. Judged by their language, most of the huēhuetlàtolli seemed to have evolved over several centuries, predating the Aztecs and most likely adopted from other Nahua cultures.

At 15, all boys and girls went to school. The china, one of the Aztec groups, were one of the first people in the world to have mandatory education for nearly all children, regardless of gender, rank, or station. There were two types of schools: the telpochcalli, for practical and military studies, and the calmecac, for advanced learning in writing, astronomy, statesmanship, theology, and other areas. The two institutions seem to be common to the Nahua people, leading some experts to suggest that they are older than the Aztec culture.

Aztec teachers (tlatimine) propounded a spartan regime of education with the purpose of forming a stoical people.

Girls were educated in the crafts of home and child raising. They were not taught to read or write. All women were taught to be involved in religion; there are paintings of women presiding over religious ceremonies, but there are no references to female priests.

Inca

Inca education during the time of the Inca Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries was divided into two principal spheres: education for the upper classes and education for the general population. The royal classes and a few specially chosen individuals from the provinces of the Empire were formally educated by the Amautas (wise men), while the general population learned knowledge and skills from their immediate forebears.

The Amautas constituted a special class of wise men similar to the bards of Great Britain. They included illustrious philosophers, poets, and priests who kept the oral histories of the Incas alive by imparting the knowledge of their culture, history, customs and traditions throughout the kingdom. Considered the most highly educated and respected men in the Empire, the Amautas were largely entrusted with educating those of royal blood, as well as other young members of conquered cultures specially chosen to administer the regions. Thus, education throughout the territories of the Incas was socially discriminatory, most people not receiving the formal education that royalty received.

The official language of the empire was Quechua, although dozens if not hundreds of local languages were spoken. The Amautas did ensure that the general population learn Quechua as the language of the Empire, much in the same way the Romans promoted Latin throughout Europe; however, this was done more for political reasons than educational ones.

After the 15th century

China

In the 1950s, The Chinese Communist Party oversaw the rapid expansion of primary education throughout China. At the same time, it redesigned the primary school curriculum to emphasize the teaching of practical skills in an effort to improve the productivity of future workers. Paglayan [70] notes that Chinese news sources during this time cited the eradication of illiteracy as necessary “to open the way for development of productivity and technical and cultural revolution”.[71] Chinese government officials noted the interrelationship between education and “productive labor” [72] Like in the Soviet Union, the Chinese government expanded education provision among other reasons to improve their national economy.

Europe overview

Modern systems of education in Europe derive their origins from the schools of the High Middle Ages. Most schools during this era were founded upon religious principles with the primary purpose of training the clergy. Many of the earliest universities, such as the University of Paris founded in 1160, had a Christian basis. In addition to this, a number of secular universities existed, such as the University of Bologna, founded in 1088. Free education for the poor was officially mandated by the Church in 1179 when it decreed that every cathedral must assign a master to teach boys too poor to pay the regular fee;[73] parishes and monasteries also established free schools teaching at least basic literary skills. With few exceptions, priests and brothers taught locally, and their salaries were frequently subsidized by towns. Private, independent schools reappeared in medieval Europe during this time, but they, too, were religious in nature and mission.[74] The curriculum was usually based around the trivium and to a lesser extent quadrivium (the seven Artes Liberales or Liberal arts) and was conducted in Latin, the lingua franca of educated Western Europe throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance.[75]

In northern Europe this clerical education was largely superseded by forms of elementary schooling following the Reformation. In Scotland, for instance, the national Church of Scotland set out a programme for spiritual reform in January 1561 setting the principle of a school teacher for every parish church and free education for the poor. This was provided for by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland, passed in 1633, which introduced a tax to pay for this programme. Although few countries of the period had such extensive systems of education, the period between the 16th and 18th centuries saw education become significantly more widespread.[76]

Herbart developed a system of pedagogy widely used in German-speaking areas. Mass compulsory schooling started in Prussia c1800 to "produce more soldiers and more obedient citizens"

Central and Eastern Europe

In Central Europe, the 17th century scientist and educator John Amos Comenius promulgated a reformed system of universal education that was widely used in Europe. Its growth resulted in increased government interest in education. In the 1760s, for instance, Ivan Betskoy was appointed by the Russian Tsarina, Catherine II, as educational advisor. He proposed to educate young Russians of both sexes in state boarding schools, aimed at creating "a new race of men". Betskoy set forth a number of arguments for general education of children rather than specialized one: "in regenerating our subjects by an education founded on these principles, we will create... new citizens." Some of his ideas were implemented in the Smolny Institute that he established for noble girls in Saint Petersburg.[77]

Poland established in 1773 of a Commission of National Education (Polish: Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, Lithuanian: Nacionaline Edukacine Komisija). The commission functioned as the first government Ministry of Education in a European country.[78]

Universities

By the 18th century, universities published academic journals; by the 19th century, the German and the French university models were established. The French established the Ecole Polytechnique in 1794 by the mathematician Gaspard Monge during the French Revolution, and it became a military academy under Napoleon I in 1804. The German university — the Humboldtian model — established by Wilhelm von Humboldt was based upon Friedrich Schleiermacher's liberal ideas about the importance of seminars, and laboratories. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the universities concentrated upon science, and served an upper class clientele. Science, mathematics, theology, philosophy, and ancient history comprised the typical curriculum.

Increasing academic interest in education led to analysis of teaching methods and in the 1770s the establishment of the first chair of pedagogy at the University of Halle in Germany. Contributions to the study of education elsewhere in Europe included the work of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in Switzerland and Joseph Lancaster in Britain.

In 1884, a groundbreaking education conference was held in London at the International Health Exhibition, attracting specialists from all over Europe.[79]

19th century

In the late 19th century, most of West, Central, and parts of East Europe began to provide elementary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic, partly because politicians believed that education was needed for orderly political behavior. As more people became literate, they realized that most secondary education was only open to those who could afford it. Having created primary education, the major nations had to give further attention to secondary education by the time of World War I.[80]

20th century

In the 20th century, new directions in education included, in Italy, Maria Montessori's Montessori schools; and in Germany, Rudolf Steiner's development of Waldorf education.

France

In the Ancien Régime before 1789, educational facilities and aspirations were becoming increasingly institutionalized primarily in order to supply the church and state with the functionaries to serve as their future administrators. France had many small local schools where working-class children — both boys and girls — learned to read, the better to know, love and serve God. The sons and daughters of the noble and bourgeois elites, however, were given quite distinct educations: boys were sent to upper school, perhaps a university, while their sisters perhaps were sent for finishing at a convent. The Enlightenment challenged this old ideal, but no real alternative presented itself for female education. Only through education at home were knowledgeable women formed, usually to the sole end of dazzling their salons.[81]

The modern era of French education begins in the 1790s. The Revolution in the 1790s abolished the traditional universities.[82] Napoleon sought to replace them with new institutions, the Polytechnique, focused on technology.[83] The elementary schools received little attention until 1830, when France copied the Prussian education system.

In 1833, France passed the Guizot Law, the first comprehensive law of primary education in France. This law mandated all local governments to establish primary schools for boys. It also established a common curriculum focused on moral and religious education, reading, and the system of weights and measurements. The expansion of education provision under the Guizot law was largely motivated by the July Monarchy’s desire to shape the moral character of future French citizens with an eye toward promoting social order and political stability.

Jules Ferry, an anti-clerical politician holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, created the modern Republican school (l'école républicaine) by requiring all children under the age of 15—boys and girls—to attend. see Jules Ferry laws Schools were free of charge and secular (laïque). The goal was to break the hold of the Catholic Church and monarchism on young people. Catholic schools were still tolerated but in the early 20th century the religious orders sponsoring them were shut down.[84][85]

French Empire

French colonial officials, influenced by the revolutionary ideal of equality, standardized schools, curricula, and teaching methods as much as possible. They did not establish colonial school systems with the idea of furthering the ambitions of the local people, but rather simply exported the systems and methods in vogue in the mother nation.[86] Having a moderately trained lower bureaucracy was of great use to colonial officials.[87] The emerging French-educated indigenous elite saw little value in educating rural peoples.[88] After 1946 the policy was to bring the best students to Paris for advanced training. The result was to immerse the next generation of leaders in the growing anti-colonial diaspora centered in Paris. Impressionistic colonials could mingle with studious scholars or radical revolutionaries or so everything in between. Ho Chi Minh and other young radicals in Paris formed the French Communist party in 1920.[89]

Tunisia was exceptional. The colony was administered by Paul Cambon, who built an educational system for colonists and indigenous people alike that was closely modeled on mainland France. He emphasized female and vocational education. By independence, the quality of Tunisian education nearly equalled that in France.[90]

African nationalists rejected such a public education system, which they perceived as an attempt to retard African development and maintain colonial superiority. One of the first demands of the emerging nationalist movement after World War II was the introduction of full metropolitan-style education in French West Africa with its promise of equality with Europeans.[91][92]

In Algeria, the debate was polarized. The French set up schools based on the scientific method and French culture. The Pied-Noir (Catholic migrants from Europe) welcomed this. Those goals were rejected by the Moslem Arabs, who prized mental agility and their distinctive religious tradition. The Arabs refused to become patriotic and cultured Frenchmen and a unified educational system was impossible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies went into exile after 1962.[93]

In South Vietnam from 1955 to 1975 there were two competing colonial powers in education, as the French continued their work and the Americans moved in. They sharply disagreed on goals. The French educators sought to preserving French culture among the Vietnamese elites and relied on the Mission Culturelle – the heir of the colonial Direction of Education – and its prestigious high schools. The Americans looked at the great mass of people and sought to make South Vietnam a nation strong enough to stop communism. The Americans had far more money, as USAID coordinated and funded the activities of expert teams, and particularly of academic missions. The French deeply resented the American invasion of their historical zone of cultural imperialism.[94]

England

In 1818, John Pounds set up a school and began teaching poor children reading, writing, and mathematics without charging fees. In 1820, Samuel Wilderspin opened the first infant school in Spitalfield. Starting in 1833, Parliament voted money to support poor children's school fees in England and Wales.[95] In 1837, the Whig Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham led the way in preparing for public education. Most schooling was handled in church schools, and religious controversies between the Church of England and the dissenters became a central theme and educational history before 1900.[96]

Scotland

Scotland has a separate system. See History of education in Scotland.

Denmark

The Danish education system has its origin in the cathedral- and monastery schools established by the Church; and seven of the schools established in the 12th and 13th centuries still exist today. After the Reformation, which was officially implemented in 1536, the schools were taken over by the Crown. Their main purpose was to prepare the students for theological studies by teaching them Latin and Greek. Popular elementary education was at that time still very primitive, but in 1721, 240 rytterskoler ("cavalry schools") were established throughout the kingdom. Moreover, the religious movement of Pietism, spreading in the 18th century, required some level of literacy, thereby promoting the need for public education. Throughout the 19th century (and even up until today), the Danish education system was especially influenced by the ideas of clergyman, politician and poet N. F. S. Grundtvig, who advocated inspiring methods of teaching and the foundation of folk high schools. In 1871, there was a division of the secondary education into two lines: the languages and the mathematics-science line. This division was the backbone of the structure of the Gymnasium (i.e. academic general upper secondary education programme) until the year 2005.[97]

In 1894, the Folkeskole ("public school", the government-funded primary education system) was formally established (until then, it had been known as Almueskolen ("common school")), and measures were taken to improve the education system to meet the requirements of industrial society.

In 1903, the 3-year course of the Gymnasium was directly connected the municipal school through the establishment of the mellemskole ('middle school', grades 6–9), which was later on replaced by the realskole. Previously, students wanting to go to the Gymnasium (and thereby obtain qualification for admission to university) had to take private tuition or similar means as the municipal schools were insufficient.

In 1975, the realskole was abandoned and the Folkeskole (primary education) transformed into an egalitarian system where pupils go to the same schools regardless of their academic merits.

Norway

Shortly after Norway became an archdiocese in 1152, cathedral schools were constructed to educate priests in Trondheim, Oslo, Bergen and Hamar. After the reformation of Norway in 1537, (Norway entered a personal union with Denmark in 1536) the cathedral schools were turned into Latin schools, and it was made mandatory for all market towns to have such a school. In 1736 training in reading was made compulsory for all children, but was not effective until some years later. In 1827, Norway introduced the folkeskole, a primary school which became mandatory for 7 years in 1889 and 9 years in 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s, the folkeskole was abolished, and the grunnskole was introduced.[98]

In 1997, Norway established a new curriculum for elementary schools and middle schools. The plan is based on ideological nationalism, child-orientation, and community-orientation along with the effort to publish new ways of teaching.[99]

Sweden

In 1842, the Swedish parliament introduced a four-year primary school for children in Sweden, "folkskola". In 1882 two grades were added to "folkskola", grade 5 and 6. Some "folkskola" also had grade 7 and 8, called "fortsättningsskola". Schooling in Sweden became mandatory for 7 years in the 1930s and for 8 years in the 1950s and for 9 years in 1962,[100][101]

According to Lars Petterson, the number of students grew slowly, 1900–1947, then shot up rapidly in the 1950s, and declined after 1962. The pattern of birth rates was a major factor. In addition Petterson points to the opening up of the gymnasium from a limited upper social base to the general population based on talent. In addition he points to the role of central economic planning, the widespread emphasis on education as a producer of economic growth and the expansion of white collar jobs.[102]

Japan

Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world in the year 1600 under the Tokugawa regime (1600–1867). In 1600 very few common people were literate. By the period's end, learning had become widespread. Tokugawa education left a valuable legacy: an increasingly literate populace, a meritocratic ideology, and an emphasis on discipline and competent performance. Traditional Samurai curricula for elites stressed morality and the martial arts. Confucian classics were memorized, and reading and recitation of them were common methods of study. Arithmetic and calligraphy were also studied. Education of commoners was generally practically oriented, providing basic three Rs, calligraphy and use of the abacus. Much of this education was conducted in so-called temple schools (terakoya), derived from earlier Buddhist schools. These schools were no longer religious institutions, nor were they, by 1867, predominantly located in temples. By the end of the Tokugawa period, there were more than 11,000 such schools, attended by 750,000 students. Teaching techniques included reading from various textbooks, memorizing, abacus, and repeatedly copying Chinese characters and Japanese script. By the 1860s, 40–50% of Japanese boys, and 15% of the girls, had some schooling outside the home. These rates were comparable to major European nations at the time (apart from Germany, which had compulsory schooling).[103] Under subsequent Meiji leadership, this foundation would facilitate Japan's rapid transition from feudal society to modern nation which paid very close attention to Western science, technology and educational methods.

Meiji reforms

After 1868 reformers set Japan on a rapid course of modernization, with a public education system like that of Western Europe. Missions like the Iwakura mission were sent abroad to study the education systems of leading Western countries. They returned with the ideas of decentralization, local school boards, and teacher autonomy. Elementary school enrolments climbed from about 40 or 50 per cent of the school-age population in the 1870s to more than 90 per cent by 1900, despite strong public protest, especially against school fees.

A modern concept of childhood emerged in Japan after 1850 as part of its engagement with the West. Meiji era leaders decided the nation-state had the primary role in mobilizing individuals – and children – in service of the state. The Western-style school became the agent to reach that goal. By the 1890s, schools were generating new sensibilities regarding childhood.[104] After 1890 Japan had numerous reformers, child experts, magazine editors, and well-educated mothers who bought into the new sensibility. They taught the upper middle class a model of childhood that included children having their own space where they read children's books, played with educational toys and, especially, devoted enormous time to school homework. These ideas rapidly disseminated through all social classes[105][106]

After 1870 school textbooks based on Confucianism were replaced by westernized texts. However, by the 1890s, a reaction set in and a more authoritarian approach was imposed. Traditional Confucian and Shinto precepts were again stressed, especially those concerning the hierarchical nature of human relations, service to the new state, the pursuit of learning, and morality. These ideals, embodied in the 1890 Imperial Rescript on Education, along with highly centralized government control over education, largely guided Japanese education until 1945, when they were massively repudiated.[107]

India

Education was widespread for elite young men in the 18th century, with schools in most regions of the country. The subjects taught included Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Theology, Law, Astronomy, Metaphysics, Ethics, Medical Science and Religion.

The current system of education, with its western style and content, was introduced and founded by the British during the British Raj, following recommendations by Lord Macaulay, who advocated for the teaching of English in schools and the formation of a class of Anglicized Indian interpreters.[108] Traditional structures were not recognized by the British government and have been on the decline since.

Public education expenditures in the late 19th and early 20th centuries varied dramatically across regions with the western and southern provinces spending three to four times as much as the eastern provinces. Much of the inter-regional differential was due to historical differences in land taxes, the major source of revenue.[109]

Lord Curzon, the Viceroy 1899–1905, made mass education a high priority after finding that no more than 20% of India's children attended school. His reforms centered on literacy training and on restructuring of the university systems. They stressed ungraded curricula, modern textbooks, and new examination systems. Curzon's plans for technical education laid the foundations which were acted upon by later governments.[110]

Australia, Canada, New Zealand

In Canada, education became a contentious issue after Confederation in 1867, especially regarding the status of French schools outside Quebec.

Education in New Zealand began with provision made by the provincial government, the missionary Christian churches and private education. The first act of parliament for education was passed in 1877, and sought to establish a standard for primary education. It was compulsory for children to attend school from the age of 6 until the age of 16 years.[111]

In Australia, compulsory education was enacted in the 1870s, and it was difficult to enforce. People found it hard to afford for school fees. Moreover, teachers felt that they did not get a high salary for what they did.[112]

Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union

In Imperial Russia, according to the 1897 census, literate people made up 28 per cent of the population. There was a strong network of universities for the upper class, but weaker provisions for everyone else.

Vladimir Lenin, in 1919 proclaimed the major aim of the Soviet government was the abolition of illiteracy. A system of universal compulsory education was established. Millions of illiterate adults were enrolled in special literacy schools. Youth groups (Komsomol members and Young Pioneer) were utilized to teach. In 1926, the literacy rate was 56.6 per cent of the population. By 1937, according to census data, the literacy rate was 86% for men and 65% for women, making a total literacy rate of 75%.

The fastest expansion of primary schooling in the history of the Soviet Union coincided with the First Five-Year Plan. The motivation behind this rapid expansion of primary education can largely be attributed to Stalin’s interest in ensuring that everyone would have the skills and predisposition necessary to contribute to the state’s industrialization and international supremacy goals. Indeed, Paglayan [70] notes that one of the things that most surprised U.S. officials during their education missions to the USSR was, in U.S. officials’ own words, “the extent to which the Nation is committed to education as a means of national advancement. In the organization of a planned society in the Soviet Union, education is regarded as one of the chief resources and techniques for achieving social, economic, cultural, and scientific objectives in national interest. Tremendous responsibilities are therefore placed on Soviet schools, and comprehensive support is provided for them” [113]

An important aspect of the early campaign for literacy and education was the policy of "indigenization" (korenizatsiya). This policy, which lasted essentially from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s, promoted the development and use of non-Russian languages in the government, the media, and education. Intended to counter the historical practices of Russification, it had as another practical goal assuring native-language education as the quickest way to increase educational levels of future generations. A huge network of so-called "national schools" was established by the 1930s, and this network continued to grow in enrolments throughout the Soviet era. Language policy changed over time, perhaps marked first of all in the government's mandating in 1938 the teaching of Russian as a required subject of study in every non-Russian school, and then especially beginning in the latter 1950s a growing conversion of non-Russian schools to Russian as the main medium of instruction.

United States

Turkey

In the 1920s and 1930s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938) imposed radical educational reforms in trying to modernize Turkey. He first separated of governmental and religious affairs. Education was the cornerstone in this effort. In 1923, there were three main educational groups of institutions. The most common institutions were medreses based on Arabic, the Qur'an, and memorization. The second type of institution was idadî and sultanî, the reformist schools of the Tanzimat era. The last group included colleges and minority schools in foreign languages that used the latest teaching models in educating pupils. The old medrese education was modernized.[114] Atatürk changed the classical Islamic education for a vigorously promoted reconstruction of educational institutions.[114] He linked educational reform to the liberation of the nation from dogma, which he believed was more important than the Turkish War of Independence. He declared:

Today, our most important and most productive task is the national education [unification and modernization] affairs. We have to be successful in national education affairs and we shall be. The liberation of a nation is only achieved through this way."[115]

In 1924, Atatürk invited American educational reformer John Dewey to Ankara to advise him on how to reform Turkish education.[116] Unification was put into force in 1924, making education inclusive and organized on a model of the civil community. In this new design, all schools submitted their curriculum to the "Ministry of National Education", a government agency modelled after other countries' ministries of education. Concurrently, the republic abolished the two ministries and made clergy subordinate to the department of religious affairs, one of the foundations of secularism in Turkey. The unification of education under one curriculum ended "clerics or clergy of the Ottoman Empire", but was not the end of religious schools in Turkey; they were moved to higher education until later governments restored them to their former position in secondary after Atatürk's death.

In the 1930s, at the suggestion of Albert Einstein, Atatürk hired over a thousand established academics, including world renowned émigré professors escaping the Nazi takeover in Germany. Most were in medicine, mathematics, and natural science, plus a few in the faculties of law and the arts. Germany’s exiled professors served as directors in eight of twelve Istanbul’s basic science Institutes, as well as six directors of Istanbul’s seventeen clinics at the Faculty of Medicine.[117][118]

Africa

Education in French controlled West Africa during the late 1800s and early 1900s was different from the nationally uniform compulsory education of France in the 1880s. "Adapted education" was organized in 1903 and used the French curriculum as a basis, replacing information relevant to France with "comparable information drawn from the African context". For example, French lessons of morality were coupled with many references to African history and local folklore. The French language was also taught as an integral part of adapted education.

Africa has more than 40 million children. According to UNESCO's Regional overview on sub-Saharan Africa, in 2000 only 58% of children were enrolled in primary schools, the lowest enrolment rate of any region. The USAID Center reports as of 2005, forty per cent of school-aged children in Africa do not attend primary school.

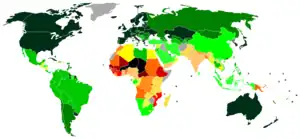

Recent world-wide trends

- 0.950 and over

- 0.900–0.949

- 0.850–0.899

- 0.800–0.849

- 0.750–0.799

- 0.700–0.749

- 0.650–0.699

- 0.600–0.649

- 0.550–0.599

- 0.500–0.549

- 0.450–0.499

- 0.400–0.449

- 0.350–0.399

- under 0.350

- not available

Today, there is some form of compulsory education in most countries. Due to population growth and the proliferation of compulsory education, UNESCO has calculated that in the next 30 years more people will receive formal education than in all of human history thus far.

Illiteracy and the per centage of populations without any schooling have decreased in the past several decades. For example, the percentage of population without any schooling decreased from 36% in 1960 to 25% in 2000.

Among developing countries, illiteracy and percentages without schooling in 2000 stood at about half the 1970 figures. Among developed countries, figures about illiteracy rates differ widely. Often it is said that they decreased from 6% to 1%. Illiteracy rates in less economically developed countries (LEDCs) surpassed those of more economically developed countries (MEDCs) by a factor of 10 in 1970, and by a factor of about 20 in 2000. Illiteracy decreased greatly in LEDCs, and virtually disappeared in MEDCs. Percentages without any schooling showed similar patterns.

Percentages of the population with no schooling varied greatly among LEDCs in 2000, from less than 10% to over 65%. MEDCs had much less variation, ranging from less than 2% to 17%.

Since the mid-20th century, societies around the globe have undergone an accelerating pace of change in economy and technology. Its effects on the workplace, and thus on the demands on the educational system preparing students for the workforce, have been significant. Beginning in the 1980s, government, educators, and major employers issued a series of reports identifying key skills and implementation strategies to steer students and workers towards meeting the demands of the changing and increasingly digital workplace and society. 21st century skills are a series of higher-order skills, abilities, and learning dispositions that have been identified as being required for success in 21st century society and workplaces by educators, business leaders, academics, and governmental agencies. Many of these skills are also associated with deeper learning, including analytic reasoning, complex problem solving, and teamwork, compared to traditional knowledge-based academic skills.

See also

References

- See James Bowen, A History of Western Education (3 vol 1981) online

- Gary McCulloch and David Crook, eds. The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Education (2013)

- Penelope Peterson, et al. eds. International Encyclopedia of Education (3rd ed. 8 vol 2010) comprehensive coverage for every nation

- Parsons, Marie. "Education in Ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt.

- Thomason, Allison Karmel (2005). Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-0238-9, ISBN 978-0-7546-0238-5, p. 25.

- Rivkah Harris (2000). Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). A History of Writing. Reaktion Books, ISBN 1-86189-167-9, p. 50.

- "Ashurbanipal – king of Assyria".

- Baines, John (1983), Literacy and Ancient Egyptian Society, pp. 572–599

- Redford, Donald (2000). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 67, 94.

- Baines, John (2007). Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 67, 94.

- Literacy University College London

- Hopkins K "Conquest by book", 1991, p. 135. in JH Humphrey (ed.) Literacy in the Roman World (Journal of Roman Archeology, Supplementary Series No 3, pp. 133–158), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

- Baines, John "Literacy and ancient Egyptian society", 1983, Man (New Series), 18 (3), 572–599

- Lesko, L. (1994). Pharaoh's Workers: The Villagers of Deir el Medina. Cornell University Press. pp. 67, 94.

- Village Voices: Proceedings of the Symposium "Texts from Deir El-Medîna and Their Interpretation". Centre of Non-Western Studies, Leiden university. 1991. pp. 81–94.

- Literacy University College London

- Compayre, Gabriel; Payne, W. H., History of Pedagogy (1899), Translated by W. H. Payne, 2003, Kessinger Publishing; ISBN 0-7661-5486-6; p. 9.

- Hezser, Catherine "Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine", 2001, Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism; 81. Tuebingen: Mohr-Siebeck, at page 503.

- Bar-Ilan, M. "Illiteracy in the Land of Israel in the First Centuries C.E." Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine in S. Fishbane, S. Schoenfeld and A. Goldschlaeger (eds.), Essays in the Social Scientific Study of Judaism and Jewish Society, II, New York: Ktav, 1992, pp. 46–61.

- Al-Hassani, S. T. S. (2011). 1001 inventions: Muslim heritage in our world. Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation Ltd.

- Gupta, Amita. Going to School in South Asia, 2007, Greenwood Publishing Group; ISBN 978-0-313-33553-2; pp. 73-76

- "True Hindu Greatness". 21 November 2014.

- Jain, Richa (20 April 2018). "What Did the Ancient Indian Education System Look Like?". Culture Trip. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Brockington, John (2003). "The Sanskrit Epics". In Flood, Gavin (ed.). Blackwell companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 116–128. ISBN 0-631-21535-2.

- Hartmut Scharfe (2002). Education in Ancient India. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-12556-6.

- Majumdar, Raychauduri; Majumdar, Datta (1946). An Advanced History of India. London: Macmillan. p. 64.

- UNESCO World Heritage List. 1980. Taxila: Brief Description. Retrieved 13 January 2007

- "History of Education", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- "Nalanda" (2007). Encarta.

- Joseph Needham (2004), Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-36166-4:

When the men of Alexander the Great came to Taxila in India in the fourth century BC they found a university there the like of which had not been seen in Greece, a university which taught the Trayi Veda and the eighteen accomplishments and was still existing when the Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hsien went there about AD 400.

- Jing Lin, Education in Post-Mao China (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1993)

- Kinney, Anne B; Representations of Childhood and Youth in Early China, 2004, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4731-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-4731-8 at pp. 14–15

- Foster, Philip; Purves, Alan: "Literacy and society with particular reference to the non-Western world" in Handbook of Reading Research by Rebecca Barr, P. David Pearson, Michael L. Kamil, Peter Mosenthal 2002, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002; Originally published: New York : Longman, c. 1984 – c. 1991; p. 30.

- Coulson, Joseph: Market Education: The Unknown History, 1999, Transaction Publishers; ISBN 1-56000-408-8, ISBN 978-1-56000-408-0; pp. 40–47

- Cordasco, Francesco: A Brief History of Education: A Handbook of Information on Greek, Roman, Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern Educational Practice, 1976, Rowman & Littlefield; ISBN 0-8226-0067-6, ISBN 978-0-8226-0067-1; at pp. 5, 6, & 9

- Michael Chiappetta, "Historiography and Roman Education", History of Education Journal 4, no. 4 (1953): 149–156.

- Harris W.V. Ancient literacy, 1989, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., p. 158

- Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, Third Edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1996

- Quintilian, Quintilian on Education, translated by William M. Smail (New York: Teachers College Press, 1966).

- Yun Lee Too, Education in Greek and Roman antiquity (Boston: Brill, 2001).

- H. V. Harris, Ancient literacy (Harvard University Press, 1989) p. 328.

- J. Wright, Brian (2016). ""Ancient Rome's Daily News Publication With Some Likely Implications For Early Christian Studies" TynBull 67.1". Tyndale Bulletin. 67 (1): 145–160. doi:10.53751/001c.29414. S2CID 239948306.

- Lynch, Sarah B. (May 2021). "Marking Time, Making Community in Medieval Schools". History of Education Quarterly. 61 (2): 158-180. doi:10.1017/heq.2021.7.

- Riché, Pierre (1978): Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126–7, 282–98

- Southern, R.W. (1982). Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century. Harvard University Press. pp. 114, 115.

- Goffart, Walter. The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon (Princeton University Press, 1988) pp. 238ff.

- Eleanor S. Duckett, Alcuin, Friend of Charlemagne: His World and his Work (1965)

- Carolingian schools#Further ambition

- Joseph W. Koterski (2005). Medieval Education. Fordham U. Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8232-2425-8.

- Stanley E. Porter, Dictionary of biblical criticism and interpretation (2007) p. 223

- "Oldest higher-learning institution, oldest university".

- Verger, Jacques: "Patterns", in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8, pp. 35–76 (35)

- George Modelski, World Cities: –3000 to 2000, Washington DC: FAROS 2000, 2003. ISBN 978-0-9676230-1-6. See also Evolutionary World Politics Homepage. Archived 28 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. "Madrasa". Encyclopaedia of Islam, (2nd ed. 2010)

- George Makdisi: "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages", in: Studia Islamica, Vol. 32 (1970), S. 255–264 (264)

- Alatas, Syed Farid (2006). "From Jami'ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue". Current Sociology. 54 (1): 112–32. doi:10.1177/0011392106058837. S2CID 144509355.

- "Les manuscrits trouvés à Tombouctou" (in French). 1 August 2004.

- "Reclaiming the Ancient Manuscripts of Timbuktu".

- Norman, Jerry (2005). "Chinese Writing: Transitions and Transformations". Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- K. S. Tom. [1989] (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1285-9

- Yuan, Zheng. "Local Government Schools in Sung China: A Reassessment", History of Education Quarterly (Volume 34, Number 2; Summer 1994): 193–213; pp. 196–201.

- Suresh Kant Sharma (2005). Encyclopaedia of Higher Education: Historical survey-pre-independence period. Mittal Publications. pp. 4ff. ISBN 978-81-8324-013-0.

- Radhakumud Mookerji (1990). Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 587ff. ISBN 978-81-208-0423-4.

- Aryabhata. Aryabhatiya (PDF).

- "Hindu Education in the Medieval Times | India". History Discussion – Discuss Anything About History. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Islamic Education During Medieval India". Your Article Library. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Pankaj Goyal, "Education in Pre-British India"

- N Jayapalan, History Of Education In India (2005) excerpt and text search; Ram Nath Sharma, History of education in India (1996) excerpt and text search

- Paglayan, Agustina S. (February 2021). "The Non-Democratic Roots of Mass Education: Evidence from 200 Years". American Political Science Review. 115 (1): 179–198. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000647. ISSN 0003-0554.

- US Dept of State 1962, 58

- “Education Must Be Combined with Productive Labor,” published in Red Flag, cited in US Dept of State 1962, 58; People’s Daily, cited in US Dept of State 1962, 59, cited in Paglayan 2021

- Orme, Nicholas (2006). Medieval Schools. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- John M. Jeep, Medieval Germany: an encyclopedia (2001) p. 308

- Arthur A. Tilley, Medieval France: A Companion to French Studies (2010) p. 213