History of Harringay (1750–1880)

This significant period in Harringay's history witnessed the transition from a purely pastoral society and set the stage for the upheavals of the late 19th century.

| Part of a series on |

| Harringay |

|---|

| History |

| Locations |

| Other |

|

A period of change

Over the 130 years covered by this article London’s phenomenal growth was to have a decisive and permanent effect on Harringay. In 1750 London’s population stood at 700,000. By 1801 it was close to a million and became Europe’s largest city; thirty years later this figure had climbed to nearly 1.7 million and it had become the world’s biggest city. In 1851, London's population had grown to nearly 2.5 million and in 1891 it stood at over 5.5 million.[1]

Harringay – 18th & 19th century leisure destination

This break-neck growth created an ever-increasing pressure for release from a crowded city. The earliest effects on Harringay were to be felt as the Southernmost part of the area became an immensely popular leisure destination for Londoners.

Hornsey Wood House

Shortly after 1750 Old Copt Hall evolved from a residence to a popular tea house and tavern. From the 1750s on it became a popular place for Londoners to escape from the smoke and grime of the city and relax in green and pleasant surroundings. In 1758 it was reported to be the most popular resort in the area [2] An early nineteenth century writer described a peaceful retreat:

The old Hornsey Wood House well became its situation; it was embowered, and seemed a part of the wood. Two sisters, a Mrs. Lloyd and a Mrs. Collier, kept the house; they were ancient women, large in size, and usually sat before their door on a seat fixed between two venerable oaks, wherein swarms of bees hived themselves. Here the venerable and cheerful dames tasted many a refreshing cup with their good-natured customers, and told tales of bygone days, till, in very old age, one of them passed to her grave, and the other followed in a few months afterwards.[3]

The two sisters died in the 1790s and in 1796 the old house was pulled down and the oaks felled to make way for a new private leisure park. This included a much larger incarnation of the Hornsey Wood Tavern, together with a lake for fishing and boating at the top of the hill, and pleasure grounds laid out in the space created by the felling of much of the woodland. The new facility became even more successful than its predecessor. An article in the Sportsman magazine of 1846 gave a good account of the entertainments offered:

.jpg.webp)

Sports of almost every kind here ready to the seeker. Cricket, coursing, rabbit and pigeon shooting, skittles, dutch pins, four corners, quoits and rowing matches…and in the time of the third George, cock-fighting was one of its most popular attractions and was frequently patronised by that "first gentleman in the world" and accomplished scapegrace, his eldest son, who, with the Dukes of York and Clarence, Colonel Hanger, Sheridan, and a host of bon vivans (sic), often sported (here)….

In 1866 the demand for public recreation spaces overtook the Hornsey Wood Tavern. The house and its amenities were swept away to make way for the new Finsbury Park.

Finsbury Park

In 1841 the people of Finsbury in the City of London petitioned for a park to alleviate conditions of the poor of London. The present-day site of Finsbury Park was one of four suggestions for the location of a park. Originally to be named Albert Park, the first plans were drawn up in 1850. Renamed Finsbury Park, plans for the park's creation were finally ratified by an Act of Parliament in 1857. Despite some considerable local opposition, the park was formally opened on Saturday 7 August 1869. The old lake was extended, a tree-lined avenue planted around the park and both an American and ornamental garden laid out. Although the park's name was taken from the area where the 19th century benefactors who created it lived, years before Harringay, the Park included, had been part the Finsbury division of the Ossultone Hundred.[4]

Alexandra Palace

Close at hand, about a half-mile to the northwest of Harringay, Alexandra Palace and its park were laid out as a popular entertainment venue for the working people of north London. Designed to rival the Crystal Palace in South London, it opened to the public on 24 May 1873. The building was constructed almost entirely out of the materials of the 1862 International Exhibition (also known as the Great London Exposition). Fifteen days after it first opened, the building was gutted by fire – probably caused by some workmen who had been working on the roof of the great dome dropping lighted tobacco.

It was decided to rebuild the palace without delay and the second Alexandra Palace was opened on 1 May 1875. It contained a grand hall capable of seating 12,000 visitors; an Italian garden; a spacious court with a fine fountain; a concert-room, seating 3,500 visitors; a conservatory covered by a glass dome; two huge halls for the exhibition of works of art; a reading-room; a Moorish house and an Egyptian villa and a theatre with seating for over 3,000 people. There were also extensive facilities to feed and water the visitors including grill and coffee rooms, two banqueting rooms, drawing, billiard, and smoke rooms and a grand dining saloon, which accommodated as many as 1,000 people. The park featured a whole range of entertainment facilities including a number of Swiss chalets and other follies, an extensive ranges of greenhouses; a racecourse; a trotting ring with stabling for several hundred horses; a cricket-ground and a Japanese village, comprising a temple, a residence, and a bazaar.[4]

Queen's Head

In 1794 Harringay's first pub, the 'Queen's Head', was established as a road tavern. Well situated for visitors to Alexandra Palace in later years, it also had a tea garden. When it was modernised in 1898, the builders found a solid gold ring with an inset emerald from the 14th century. The ring was given to the British Museum where it still is today.[5]

Settlement

The desire to escape from London coupled with increasing wealth brought more than just day-trippers. As the eighteenth century drew to a close the wealthier classes increasingly chose to settle in areas close to but outside London. By the mid-nineteenth century, the area just outside Harringay to the south and southeast of Finsbury Park was becoming a London suburb. To the west, in Crouch End and Hornsey, there were a number of comfortable villas built. Yet in Harringay, right up to 1880, only a handful of larger houses and a few comfortable suburban style houses were built.

To the west of Green Lanes, just one house, Harringay House, was built prior to 1880.

Harringay House

The notion that an old Tudor House had reputedly stood at the top of the hill between present-day Allison and Hewitt Roads and was apparently demolished in 1750 is most likely a misunderstanding: no historical evidence exists for an older building.[6] The last owners of the land, the Cozens family, sold it in 1789 to Edward Gray, a linen draper of Cornhill.[7] When he acquired the land it was known as Downhill Fields.[7] It included Collier's Field, Hill Field, Pond Field, Smith Field and, Wood Field. In 1792 Gray built a large house on the site of the old house, within a loop of the New River. He named it 'Harringay House'.

During his lifetime Gray added significant lands to the original estate. In 1791 he acquired 4 acres (16,000 m2) of land called Drayner's Grove from Elizabeth Lady Colerane.[8] He subsequently acquired freehold or copyhold much of the land that now makes up the western part of Harringay. The size of his land acquisitions can be gauged by his holdings over time. He was rated for 55 acres (220,000 m2) in 1796. By 1801 he had added at least another 85 acres (340,000 m2), including Tile Kiln Field and in 1829 he was assessed on 192 acres (0.78 km2).[4]

Gray also built up huge collections of fine art, antique books and rare plants. Both his art and plant collections became famous. His art collection was described by William Buchanan as "one of the finest small collections of pictures in the country".[9] The collection included several paintings by Reubens, Rembrandt, Titian and others.[10]

His renowned collection of plants included a number of rare species including a celebrated magnolia grandiflora which was one of the best specimens in the country along with those at Syon House and Hatfield House.[11] Under Gray, Harringay also developed a notoriety for its steam-heated greenhouses - pioneering at the time. "Ten large hothouses have been heated in a masterly manner, the largest of them 550 feet (170 m) from the boiler. The houses thus heated comprised two graperies, two pineries, a peach house, a strawberry pit, a mushroom-house, in all 50,000 cubic feet (1,400 m3) of air, and in addition, it supplied a steam apparatus in the farm-yard".[11]

Gray died in 1838 and for the rest of its life the house became the seat for a series of grandees of some of London's key financial institutions. Immediately after Gray's death, the estate was purchased by Edward Chapman, a ship-owner, international merchant, director of the Bank of England,[12][13] and JP for Middlesex.

Standing in extensive gardens and a park laid out between 1800 and 1809, Harringay House was probably the largest house in the Borough of Hornsey.[14] The only picture that survives is a very indistinct image of the house in the distance (see below). However, it is still possible to have an idea of what it was like. It is known from maps that Gray built a pair of gate lodges on Drayner’s Grove and that a grand drive swept up the hill, crossing the New River on an iron bridge, to a forecourt in front of the house. For the rest, there are a number of contemporary descriptions of the house and its surrounding parkland and gardens.

Mid-nineteenth century writers left the following description:

The house is a handsome and commodious residence seated on the summit of a conical hill and is surrounded on three sides by the New River. The broad open entrances to the gates, with an appropriate lodge at each side produces a first impression favourable to, and in character with, the interior scenes. From the winding and gently-rising approach, a large smooth knoll-like hill is seen in the south-west distance; its fine flowing outlines are bare of trees, but on the sloping grounds of the park arc groups of different sizes, one is composed of several trees, and another of only two trees, by which a moving panorama is displayed with every step of the beholder. On the other side is a fine oak tree and a large plantation. The road then enters the umbrageous foliage of a large group of trees composed of oak, elm, beech and birch, then over a bridge that spans a moat-like piece of water, through a winding avenue to the east front of the house.[15]

Agreeably to the old style of laying out places of this kind, the entrance front is on that side of the mansion which contains the finest views, so that a visitor sees everything worth seeing in point of scenery before he alights from his carriage. Something has been done to counteract this, by a fringed line of trees in the fore-ground, close to the gravelled area for turning carriages on, or what may be called the arena of honour, so that the full enjoyment of the fine views is reserved for the walks in the pleasure-ground[16]

It is a proud situation; the ascent which had been gradual, easy and delightful, is now observed from the fine table-land on the summit, to be a very elevated situation, commanding an extensive prospect over the diversified scenery of the lovely country by which it is encompassed on all sides…..diversified, with wood, water and buildings.

The conservatory and greenhouse, attached to the mansion are 120 feet (37 m) long by 18 wide and 16 high: forming the two sides of a square…..In the centre area large camellia trees ….also acacias of sorts, limes, citrona (sic), cytissus, eucalyptus and epacris….The whole is heated by hot water, and forms a delightful promenade at all seasons….To the south front, on the pleasure grounds, are evergreen oaks, a tulip tree, and a handsome variegated holly… with a pleasant view of the bright waters of the New River winding through the valley. To the right are the noble magnolia trees that have contributed to the celebrity of this place…

Through the grove, that protects the mansion from the west and surly north winds, are pleasant walks that traverse the grounds and communicate with the kitchen garden. Large evergreen trees and shrubs fringe this plantation, and produce shelter and other effects not to be disregarded in scenes of extent and of grandeur. The kitchen garden, about 1-acre (4,000 m2) and half-walled in, is seated on a sloping bank and furnished with a peach house and vinery pit 40 feet (12 m) long, and vinery pit 40 feet (12 m) long, and another pit of the same length for strawberries.[15]

The interior of the house was described in great detail in the brochure produced for the sale of the house in 1883[17]

THE RESIDENCE WITH PORTICO ENTRANCE,

Approached from Two Roads, by good carriage Drive, and contains the following accommodation:On the Third Floor – Four Bedrooms.

On the Second Floor – Four bedrooms and Store Room, and W.C.

On the First Floor – Bedroom, 18ft. 6in. by 16ft. 8in.; Day Nursery, 19ft. by 13ft. 8in.; Night Nursery, 15ft. by 15ft. 4in.; Four principal Bedrooms, 23ft. by 18ft.; 14ft. 8in. by 18ft 10in.; 16ft. 8in. by 15ft.; 18ft.10in. by 23ft. 4in., respectively; Dressing Room, 17ft. by 15ft.; Bath-Room and W.C.

On the Ground Floor – Entrance Hall, 18ft. 8in. by 13ft. 6in.; Drawing Room, 28ft. by 18ft.; Small Drawing Room, 16ft. by 14ft. 8in.; Dining Room, 27ft. 8in. by 18ft. 8in.; Morning Room, 16ft. 4in. by 14ft. 9in.; School Room, 17ft. by 11ft. 10in.; Dressing Room; Library, 26ft. 8in. by 18ft.; Kitchen, 26ft. 6in. by 18ft. 6in.; Larder; Waiting Room; W.C.; and large conservatory, 68ft. by 17ft. 10in.; Conservatory-Room adjoining, 22ft. by 16ft. 6in.; with Men’s Room above.

In the Basement – Butler’s Pantry; Billiard Room; Housekeeper’s Room; Lamp Room; and Servants’ Hall.

Outbuildings

Are extensive and comprise, on the south side of Yard, Boiler House; Coach House; Potting Sheds and Fowl-house, &c.; and on the north side, Laundry, with Ironing Room above; Dairy; small Dairy and Wash-house; Stabling, with Loft; Coachman’s Room; Coach-house and Brew-house, &c.

It is also known that the occupants lived comfortable lifestyles. Records for both Chapman and Alexander showed that they employed 14 servants including gardeners, grooms and coachmen.[18]

Edward Chapman died at Harringay House on 22 March 1869[19] and the house was let to William Cleverly Alexander wealthy banker of the City bankers Alexanders, Cunliffes & Co.[20][21] Harringay's links to the Arts forged by Edward Gray were revived under the brief tenancy of collector and art connoisseur Alexander[22] and his wife who was friend to the famous painter James McNeill Whistler. For a short period Whistler became a regular visitor to the house.[23] Alexander moved out shortly after buying one of the largest private houses in Kensington, Aubrey House in Campden Hill, in 1873.[24] The last tenant and final occupant of the house was Frederick William Price, at the time Chief Acting Partner in the private bank, Child & Co., one of the oldest financial institutions in the UK. Price lived in the house with his family from 1876 (perhaps a couple of years earlier) until the house was sold for demolition.[25] By 1880, the estate had been sold to a successful Dalston-based builder, William Hodson.[26] In December 1881, Hodson sold the land to the British Land Company for housing development. In 1883 the Price family moved out of Harringay House and the British Land Company sold the portion of the estate on which the house stood by auction on 29 October 1883. The house was pulled down in 1884 or 1885 and by April of 1885 the building materials of the house were being sold by auction.

Other settlements

To the east of Green Lanes, although building activity was still very limited during this period, a number of houses were built.

The 1798 Wyburd Map shows just three buildings in (or very close to) the borders of today’s Harringay. All three were close to the east of Hanger’s Green on present day St Ann’s Road.[27] One house, referred to as 'Hanger Green House' on the later 1864 Ordnance Survey (OS) map, stood on the site of the earlier 'Hanger Barn', just to the East of where Warwick Gardens is today. It is not known whether or at what date the earlier building was replaced.

A little further west on the opposite side of the road, near today’s Brampton Road, stood another building. The 1864 OS map refers to it as 'Rose Cottage'. It is likely this was a farm building originally, taking on the more romantic name only in the Victorian period. Mrs Couchman, an early twentieth century writer recalling the past, described it as a cottage, having a verandah covered with white clematis which blossomed freely every year.[28]

Finally, the 1798 map shows a building on the triangle of land today created by the meeting of St Ann’s and Salisbury Roads. The 1864 map suggests that by that time there were six buildings which appear to be small paired cottages.

By the mid-nineteenth century the Eastern part of Harringay had experienced further development. In addition to the Hanger Green cluster, two more groups of houses had appeared; the first on Green Lanes between present day Colina and West Green Roads; the second was along Hermitage Road. On Green Lanes, the 1864 OS map shows eight semi-detached houses and one larger villa. Four of the houses stood opposite where Beresford Road is today. None remain. The other group, including the villa, shown as 'Elm House', were built on land now occupied by the 1920s block of flats called 'Mountview Court'. Hermitage Road was developed as a private road and in 1869 included just four large houses. The smallest of them, 'Swiss Cottage', stood on the corner with Green Lanes. A little further on, set back from the southern side of the road, was 'Vale House'. Further along still, where the road bends north today, was 'The Hermitage'. And beyond Harringay’s borders, opposite where Oakdale Road today joins Hermitage Road, stood 'The Retreat'. Mrs Couchman describes the road:

Leading from St Ann’s Road to the Green-lanes, was a private road, the property of Mr. Scales.[29] There were beautiful fields on either side, and half way up on the left (sic) stood four good houses, each standing in its own grounds…..”Vale House” of which the last occupier was Mr. San Giorgie. He kept an emu in the field opposite his house; children all round were very fond of going to see it….The road was enclosed with park gates at each end. In those days it was a charming walk…

Northumberland House

Just to the south of Harringay's present-day borders, a large mansion, Northumberland House, was built by 1824[30] just to the south of the New River on the east side of Green Lanes. The building, which was converted for use as a lunatic asylum as in 1826,[31] remained until the late 1950s when it was demolished and a council housing estate built on the site.

Economic history

Economic activity within Harringay was almost all agricultural. In the mid-nineteenth century a Barratt’s sweet factory was established between the Great Northern Railway and Wood Green. But the only economic activity unrelated to agriculture or leisure within Harringay was that at the tile kilns and potteries.

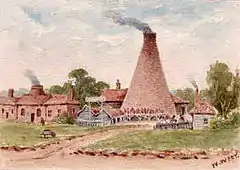

Tile kilns

In the last years of the 18th century a tile kiln was established on the site on Green Lanes now occupied by Sainsbury’s and the Arena shopping mall.[5] From the earliest days, the site was quite extensive; the Wyburd map of 1798 together with the 1864 and 1894 Ordnance Survey maps show two groups of buildings; one in the north of the site, close to where the railway now is, the other on the south of the site, reaching almost to Hermitage Road.

In 1826, although owned by Nathaniel Lee, the name of the occupier is William Scales and the site was trading as 'Scales Wm, brick and tile manufacturer'.[32] By 1843 the site was shown in rating records as 'Land & Potteries' as well as 'Tile Kilns and Land' together with '13 cottages compound'. This suggests that the two groups of buildings, although related, were producing slightly different goods. The cottages were those supplied for the workers.[33]

The January 1870 rating record suggests further expansion with a new entry for 'Brickgrounds' and the change of 'William Scales' to 'Scales & Company'. By January 1880, Scales owned some of the site alongside Lee and the whole site was occupied by W. T. Williamson, a name which became synonymous with the site in the locality where the works were known as 'Williamson's Potteries' or just 'Williamson's'. By this time, it is clear from photographs that the combined output of the sites included tiles, bricks, drain pipes and chimney pots as well as horticultural pots.[33]

Williamson's Potteries closed in 1905 and in the same year the cottages were condemned as unfit for human habitation by the Medical Officer of Health. The site then served as a rubbish tip for a number of years before being developed for Harringay Stadium and Arena.[34]

Transport

Railways

In 1852 the Great Northern Railway main line from King's Cross to Doncaster was opened. Originally, the first stop beyond London was Hornsey. In 1861 the first station at Finsbury Park opened and was originally named Seven Sisters Road (Holloway). The station at Harringay was not to open till 1885.

Tottenham & Hampstead Junction Railway opened on 21 July 1868 between Tottenham North Junction and Highgate Road. Its Harringay station, 'Green Lanes Station', was opened in 1880. The first of several name changes for the station came just three years later when it was renamed 'Harringay Park, Green Lanes'.

Roads

The Stamford Hill and Green Lanes Turnpike Trust erected a toll gate on Green Lanes by Duckett's Common, near Turnpike Lane in 1765. For the next 27 years this was the only tollgate on Green Lanes, at which time the Manor House toll gate was set up, along with others outside of the Harringay area. The turnpike system on Green Lanes was abandoned in 1872.[5] Photographs of both the "Manor House" and "Duckett's Common" turnpikes still exist today.

Seven Sisters Road was laid out in 1833 and provided a major thoroughfare along the southern edge of Harringay connecting it to Holloway, Camden and the West End of London.[35]

Highway robbery was a problem and attacks became common in the mid 18th century. In 1830, there were complaints from the residents of Stoke Newington Parish that the part of Green Lanes between Harringay and Stoke Newington was insufficiently protected.[30]

Summary

In 1750 the area that was to become Harringay was almost all agricultural land. Only two or three buildings stood within its boundaries. Over the 130 years to 1880, significant parts of it were brought into a more modern use, either as comfortable houses or as parkland. But still by 1880, less than two dozen buildings existed. However, the continuing growth of London and the consequential development of Finsbury Park, nearby Alexandra Park and most especially the building of railways were about to change things in a far more radical manner.

See also

Parish of Hornsey for the local government unit of which Harringay was part from the 17th century to 1867.

External links

- A full history of the gardens of Harringay House appears in The Gardens at Harringay House - the place, the plants the people.

- Harringay Online's History of Harringay section

- Hornsey Historical Society

- Bruce Castle Museum

- Hackney Council Archives

- London Metropolitan Archives

- Harringay online - Website for Harringay residents with lots of information on Harringay and its history.

References and notes

- "Greater London, Inner London Population & Density History". demographia.com. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- Wroth; William, Warwick; Edgar, Arthur (1896). London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century. Macmillan.

- Hone, Hurlingham (1826). Every-day Book, Volume 1.

- Walford, Edward (1878). Old and New London: Volume 5. Victoria County History.

- Pinching, Albert (2000). Wood Green Past. Philmore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-948667-64-0.

- Sherington, R.O. (1904). Story of Hornsey. F.E. Robinson & Co. In claimimg that there was a 'Tudor mansion', Sherington only refers to William Keane's description of Harringay House (see reference note below), Keane himself mentions only the fancy of a Norman castle on the site. The original source for the Tudor claim appears to have been made in 1888 by John Lloyd in his book 'History, Topography, and Antiquities of Highgate, In the County of Middlesex'. However, he offers no evidence nor reference for his claim. In fact, no evidence exists for either a Norman castle or a Tudor mansion either in maps or in texts.

- Middlesex Deeds Registers, Book 6. No. 91. 1789. Accessed at London Metropolitan Archives.

- Lysons, Daniel (1795). The Environs of London: volume 3. Victoria County History. - This land, covering roughly the area currently occupied by the houses to the East of Harringay Passage on Beresford and Allison Roads was in the Borough of Tottenham; the boundary between Tottenham and Hornsey and running roughly parallel to Green Lanes, about 200 yards (180 m) to its West.

- Buchanan, William (1824). Memoirs of Painting with a Chronolgocal History of the Importation of Pictures by the Great Masters into England since the French Revolution. Ackerman.. Buchanan was one of the leading British dealers in Old Master paintings through the first decades of the 19th Century from 1802 onwards.

- Smith, John (1829–1837). A Catalogue Raisonne of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish & French Painters, Volumes 1 -8. Smith & Son.

- Paxton, Sir Joseph (1847). Paxton's Magazine of Botany, and Register of Flowering Plants. Orr & Smith.

- Flouch, Hugh (2022). Edward Henry Chapman of Harringay House – Harringay's City merchant 'prince'. Harringay Online. Booklet available to download online via Harringay Online

- Burke, Bernard (1875). Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry. H. Colburn. Edward Chapman, born 16 January 1803, Whitby; died 22 March 1869, Harringay

- T F T Baker and C R Elrington (eds), A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton, M A Hicks and R B Pugh (1980). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 6, Friern Barnet, Finchley, Hornsey With Highgate. Victoria County History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Keane, William (1850). The Beauties of Middlesex, being a particular Description of the principal Seats of the Nobility and Gentry in the County of Middlesex.

- Gardener's Magazine. J.C. Loudon. November 1840.

- Document held at Bruce Castle Museum, Tottenham

- Aris, Alan (1986). Lost Houses of Haringey. Hornsey Historical Society. ISBN 0-903481-02-2.

- Illustrated London News - Saturday 27 March 1869

- The London Gazette, issue 23833 published on 29 February 1872. Page 439 of 456 and Debrett's House of Commons and Judicial Bench, 1882.

- Alexander, the son of George William Alexander of Surrey, married Rachel Agnes Lucas in 1861. They had three sons and seven daughters: Agnes Mary ('May') (b. 1862), Cicely Henrietta (b. 1864), Helen C. (b. ca 1865), Grace (b. 1867), Emily M. (b. ca 1871), Rachel F. (b. ca 1875) and Jean I. (b. ca 1877) (From University of Glasgow).

- The Quarterly review, Volume 298, William Gifford et al, 1960

- University of Glasgow

- Whistler advised Alexander with suggestions for the decoration of the house, "James McNeill Whistler", Hilary Taylor, 1978.

- London Gazette Issue 24300 published on 26 February 1876. Page 698 of 712, Banking Almanacs, 1879 and 1883 and the Census of 1881

- Harringay Station, The London Railway Record, No. 58, July 2008, Connor & Butler

- St Ann’s Road was called Hanger Lane in the eighteenth century. Hanger’s Green was at the junction of present day St. Ann’s Road and Black Boy Lane

- Couchman, Harriet (Mrs. J.W. Couchman) (1909). Reminiscences of Tottenham.

- Scales was also proprietor of the Tile Kilns - See section on Economic History

- A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton, Patricia E C Croot (1985). T F T Baker, C R Elrington (ed.). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8: Islington and Stoke Newington parishes. Victoria County History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Advertisement for sale of furniture from house noting the conversion for use as a private lunatic asylum in The Morning Advertiser 13 November 1826. Also Prospectus of Northumberland Ho. Asylum (1835), cited in T F T Baker, C R Elrington (Editors), A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton, Patricia E C Croot. A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8: Islington and Stoke Newington parishes (1985). Accessed online at

- (1826), Pigot's Trade Directory, Middlesex - Tottenham High Cross

- Cryer, Pat (2006). "The Tile Kilns, Tottenham, Green Lanes: history". Archived from the original on 1 July 2007.

- Ticher, Mike (2002). The Story of Harringay Stadium and Arena. Hornsey Historical Society. ISBN 0-905794-29-X.

- Robinson, William (1840). History and Antiquities of the Parish of Tottenham, 2 Vols, 2 Ed. Nicholls & Son.