History of Hesse

This article is about the history of Hesse. Hesse is a state in Germany.

.svg.png.webp)

Prehistoric

In the Paleolithic Era, the Central Hessian region around Wetzlar was settled. Extensive excavations along the Lahn in Wetzlar-Dalheim recently uncovered a 7000-year-old settlement from the Linear Pottery culture. Bell Beaker shards found in Rüsselsheim, Offenbach, Griesheim and Wiesbaden suggest settlement in southern Hesse 4,500 years ago.

Landgraviate

In 1568 with the death of Landgrave Philip I, the Landgraviate of Hesse (German: Landgrafschaft Hessen), a German Principality of the Holy Roman Empire, was divided among his sons. With the extinction of the Hesse-Marburg and Hesse-Rheinfels lines by 1604, Hesse-Darmstadt, along with Hesse-Kassel, became one of the two Hessian states. While Hesse-Kassel converted to Calvinism and became one of the most zealous exponents of the Protestant cause in the Thirty Years' War, Landgrave George II remained a strict Lutheran and maintained a close alliance with Saxony, which led to a pro-Habsburg policy after 1642.

Hesse-Darmstadt gained a great deal of territory from the secularization and modifications authorized by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803. The acquisition of the Duchy of Westphalia, formerly owned by the Archbishop of Cologne, was significant, as were the acquisition of territories from the Archbishop of Mainz and the Bishop of Worms. In 1806, upon the dissolution of the Reich and the dispossession of his cousin, the Elector of Hesse-Kassel, the Landgrave took the title of Grand Duke of Hesse.

At the Congress of Vienna, the Grand Duke was forced to cede Westphalia to Prussia. In exchange for this he received a piece of territory from the left bank of the Rhine, including the important federal fortress at Mainz. The Grand Duchy changed its name to the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine in 1816.

In 1867, the northern half of the Grand Duchy (Upper Hesse) became a part of the North German Confederation, while the half of the Grand Duchy south of the Main (Starkenburg and Rhenish Hesse) remained outside. In 1871, it became a constituent state of the German Empire. The last Grand Duke, Ernst Ludwig (a grandson of Queen Victoria and brother to Empress Alexandra of Russia), was forced from his throne at the end of World War I. The state was then renamed the Volksstaat Hessen (People's State of Hesse).

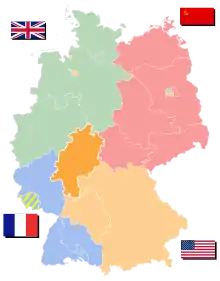

The majority of the state combined with Frankfurt am Main, the Waldeck area (Rhine-Province) and the old Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau to form the new state of Hesse following the Second World War. Excepted was the Montabaur district from Hessen-Nassau and that part of Hessen-Darmstadt on the left bank of the Rhine (Rhenish Hesse) became part of the Rhineland-Palatinate state. (Bad) Wimpfen — an exclave of Hessen-Darmstadt — became part of Baden-Württemberg, district of Sinsheim.

17th and 18th centuries

From the early years of the Reformation, the House of Hesse was predominately Protestant. Landgraves Philip I, William V, and Maurice married descendants of King George of Bohemia; from William VI onwards, mothers of the heads of Hesse-Kassel were always descended from William the Silent, the leader of the Dutch to independence on the basis of Calvinism.

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel expanded in 1604 when Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel inherited the Landgraviate of Hesse-Marburg from his childless uncle, Louis IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Marburg (1537–1604).

During the Thirty Years' War, Calvinist Hesse-Kassel proved to be Sweden's most loyal German ally. Landgrave William V and, after his death in 1637, his widow Amelia of Hanau, a granddaughter of William the Silent, as regent supported the Protestant cause and the French and Swedes throughout the war and maintained an army, garrisoning many strongholds, while Hesse-Kassel itself was occupied by Imperial troops.

William V was succeeded by Landgraves William VI and William VII. Under King Frederick I of Sweden, Hesse-Kassel was in personal union with Sweden from 1730–51. But in fact the King's younger brother, Prince William, ruled in Kassel as Regent until he succeeded his brother, reigning as William VIII until 1760.

Although it was a fairly widespread practice at the time to rent out troops to other princes, it was the Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel who became infamous for hiring out contingents of their army as mercenaries during the 17th and 18th centuries. Hesse-Kassel maintained 7% of its entire population under arms throughout the eighteenth century. This force served as a source of mercenaries for other European states.[1] Frederick II, notably, hired out so many troops to his nephew King George III of Great Britain for use in the American War of Independence, that "Hessian" has become a common term among Americans and historians for all German soldiers deployed by the British in the War. One of these regiments that saw service in America was the Musketeer Regiment Prinz Carl.

During the 17th century, the landgraviate was internally divided for dynastic purposes, without allodial rights, into:

- the Landgraviate of Hesse-Rotenburg (1627–1834)

- the Landgraviate of Hesse-Wanfried-(Rheinfels) (1649–1755)

- the Landgraviate of Hesse-Philippsthal

- Landgraviate of Hesse-Philippsthal-Barchfeld

These were reunited with the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel when each particular branch died out without issue.

19th century

Following the reorganization of the German states during the German mediatization of 1803, the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel was raised to the Electorate of Hesse and Landgrave William IX was elevated to Imperial Elector, taking the title William I, Elector of Hesse. The principality thus became known as Kurhessen, although it is still usually referred to as Hesse-Kassel.

In 1806, William I was dispossessed by Napoleon Bonaparte for his support of the Kingdom of Prussia. Kassel became the capital of a new Kingdom of Westphalia with Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte as king. The elector was restored following Napoleon's defeat in 1813, and although the Holy Roman Empire was now defunct, William retained his title of Elector, as it gave him pre-eminence over his cousin, the Grand Duke of Hesse. From 1813 onwards, the Electorate of Hesse was an independent country and, after 1815, a member of the German Confederation.

William's grandson, Elector Frederick William, sided with the Austrian Empire in the Austro-Prussian War. Following the Prussian victory his lands were annexed by Prussia in 1866. Along with the annexed Duchy of Nassau and Free City of Frankfurt, Hesse-Kassel became part of the new Province of Hesse-Nassau of the Kingdom of Prussia.

20th century

In 1918, Hesse-Nassau became part of the Free State of Prussia until 1944. From 1944–45 as part of Nazi Germany, it was divided into the Prussian provinces of Kurhessen and Nassau. From 1945–46, it was renamed Greater Hesse (German: Großhessen) and was part of the US occupation zone in Germany. From 1946 onwards, it was reorganized into the State of Hesse, a federal state of West Germany.

In 1918, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse, younger brother of the head of the house and a brother-in-law of Emperor William II, was elected by the pro-German Finnish government to be King of Finland, but he never reigned.

In 1968, the head of the House of Hesse-Kassel became the head of the entire House of Hesse due to the extinction of the House of Hesse-Darmstadt.

See also

References

- Tilly, Charles "Coercion, Capital, and European States."

Further reading

- Ingrao, Charles W. The Hessian mercenary state: ideas, institutions, and reform under Frederick II, 1760-1785 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Ingrao, Charles. "'Barbarous Strangers': Hessian State and Society during the American Revolution." American Historical Review 87.4 (1982): 954-976. online

- Wegert, Karl H. "Contention with Civility: The State and Social Control in the German Southwest, 1760–1850." Historical Journal 34.2 (1991): 349-369. online

- Wilder, Colin F. "" THE RIGOR OF THE LAW OF EXCHANGE": How People Changed Commercial Law and Commercial Law Changed People (Hesse-Cassel, 1654–1776)." Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung (2015): 629-659. online

- Clay, John-Henry (2010). In the Shadow of Death: Saint Boniface and the Conversion of Hessia, 721-54. Brepols. ISBN 9782503531618.