History of Marrakesh

The history of Marrakesh, a city in southern Morocco, stretches back nearly a thousand years. The country of Morocco itself is named after it.

Founded c. 1070 by the Almoravids as the capital of their empire, Marrakesh went on to also serve as the imperial capital of the Almohad Caliphate from 1147. The Marinids, who captured Marrakesh in 1269, relocated the capital to Fez, leaving Marrakesh as a regional capital of the south. During this period, it often broke off in rebellion into a semi-autonomous state. Marrakesh was captured by the Saadian sharifs in 1525, and resumed its status as imperial capital for a unified Morocco after they captured Fez in 1549. Marrakesh reached its epic grandeur under the Saadians, who greatly embellished the city. The Alawite sharifs captured Marrakesh in 1669. Although it served frequently as the residence of the Alawite sultans, Marrakesh was not their definitive capital, as Alawite sultans moved their courts frequently between various cities.

In the course of its history, Marrakesh achieved periods of great splendor, interrupted by repeated political struggles, military disorders, famine, plagues and a couple of sacks. Much of it was rebuilt in the 19th century. It was conquered by French troops in 1912, and became part of the French protectorate of Morocco. It remained part of the Kingdom of Morocco after independence in 1956.

Throughout its history, Marrakesh has maintained a keen rivalry with Fez as the leading city in Morocco, and the country often fragmented politically into two halves, with Fez the capital of the north and Marrakesh the capital of the south. The choice of Rabat as the capital of modern Morocco can be seen as a compromise that afforded neither of the two rival cities primacy over the other.

Foundation

The region of Marrakesh, the plain south of the Tensift River in southern Morocco, was inhabited by Berber farmers since Neolithic times, and numerous stone implements have been unearthed in the area.[1]

Before the advent of the Almoravids in the mid-11th century, the region was ruled by the Maghrawa from the city of Aghmat (which had served as a regional capital of southern Morocco since Idrisid times).[2] The Almoravids conquered Aghmat in 1058, bringing their dominance over southern Morocco. However, the Almoravid emir Abu Bakr ibn Umar soon decided Aghmat was overcrowded and unsuitable as their capital. Being originally Sanhaja Lamtuna tribesmen from the Sahara Desert, the Almoravids searched for a new location in the region that was more consonant with their customary lifestyle. After consultation with allied local Masmuda tribes, it was finally decided that the Almoravids would set up their new base on neutral territory, between the Bani Haylana and the Bani Hazmira tribes.[3] The Almoravids rode out of Aghmat and pitched their desert tents on the west bank of the small Issil river, which marked the boundary between them. The location was open and barren, it had "no living thing except gazelles and ostriches and nothing growing except lotus trees and colocynths".[3] A few kilometres to the north was the Tensift River, to the south the vast sloping plain of Haouz, pastureland suitable for their great herds. About a day's ride to the west was the fertile Nfis river valley, which would serve as the city's breadbasket. Date palms, virtually non-existent in Morocco north of the desert line, were planted around the encampment to supply the staple of Lamtuna diets.[4]

There is a dispute about the exact foundation date: chroniclers Ibn Abi Zar and Ibn Khaldun give it as c. 1061-62 while Ibn Idhari asserts that it was founded in 1070.[5] A probable reconciliation is that Marrakesh started in the 1060s, when Abu Bakr and the Almoravid chieftains first pitched their tents there, and that it remained a desert-style military encampment until the first stone building, the Qasr al-Hajar ("castle of stone", the Almoravid treasury and armory fort), was erected in May, 1070.[6] In early 1071, Abu Bakr was recalled to the Sahara to put down a rebellion, and it was his cousin (and eventual successor) Yusuf ibn Tashfin who erected the city's first brick mosque.[7] More buildings were erected soon afterwards, mud-brick houses gradually replacing the tents. The red earth used for the bricks gave Marrakesh its distinctive red color, and its popular appellation Marrakush al-Hamra ("Marrakesh the Red").[8] The layout of the buildings was still along the lines of the original encampment, with the result that early Marrakesh was an unusual-looking city, a sprawling medieval urban center evocative of desert life, with occasional tents, planted palm trees and an oasis-like feel.[9]

Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf ibn Tashfin laid the first bridge across the Tensift River to connect Marrakesh to northern Morocco,[10] but the city's life was tied to and oriented towards the south. The High Atlas range south of the city was and has always been of vital concern to Marrakesh and a great determinant of its fate. Inimical control of the Atlas mountain passes could sever Marrakesh's communications with the Sous and Draa valleys, and seal off access to the Sahara Desert and the lucrative trans-Saharan trade in salt and gold with sub-Saharan Africa (al-sudan), upon which much of its early fortunes rested. The Almoravids are said to have deliberately put the wide plain of Haouz between Marrakesh and the Atlas foothills in order to make it more defensible — by having a clear view of the distant dust clouds kicked up by any attackers coming from the Atlas, the city would have advance warning and time to prepare its defenses.[11] Nonetheless, repeatedly through its history, whoever controlled the High Atlas often ended up controlling Marrakesh as well.

Imperial capital

Marrakesh served as the capital of the vast Almoravid empire, which stretched over all of Morocco, western Algeria and southern Spain (al-Andalus). Because of the barrenness of its surroundings, Marrakesh remained merely a political and administrative capital under the Almoravids, never quite displacing bustling Aghmat, just thirty kilometres away, as a commercial or scholarly center.[12] This began to change under the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf (r.1106-1142) ("Ben Youssef"), who launched a construction program to give Marrakesh a grander feel. Ali ibn Yusuf erected a new magnificent palace, along Andalusian design, on the western side of the city, connected by a corridor to the old Qasr al-Hajar armory. More importantly, he introduced a new system of waterworks, via cisterns and khettaras (gravity-driven underground canals) designed by his engineer Abd Allah ibn Yunus al-Muhandis, that could supply the entire city with plenty of water and thus support a larger urban population.[13] Ibn Yusuf also built several monumental ablution fountains and a grand new mosque, the Masjid al-Siqaya (the first Ben Youssef Mosque), the largest mosque built in the Almoravid empire.[14] The new mosque and the surrounding markets (souqs), were set to form the center of urban life. The rest of the fledgling city was organized into neighborhoods, cut across by two grand street axes, connecting four monumental gates: Bab al-Khamis (north), Bab Aghmat (SE) and Bab Dukkala (NW) and the Bab al-Nfis (SW).[15]

The new construction boom and availability of water began to finally attract merchants and craftsmen from elsewhere, gradually turning Marrakesh into a real city. The first to arrive were the tanners, arguably Marrakesh's most famous industry.[16] (Goatskin tanned with sumac is still commonly referred to as "Moroccan leather" in English; books "bound in Moroccan leather" are synonymous with high luxury). The "dirty" industries - tanners, potters, tile-makers, dyers - were set up on the east part of town, on the other side of the Issil river, partly because of the stench, partly because of their need for the river's water.[17] Ali's irrigation system allowed a surfeit of new planted orchards, vineyards and olive gardens, which attracted oil presses and related businesses, set up on the north side of town.[15] Wealthy merchants and courtiers would go on to erect stately city homes, with Andalusian-style inner fountained garden courtyards, the riads for which Marrakesh is famous, and splendid colonnaded villas outside of it.[18]

Although the bulk of Almoravid coinage was still struck by the mints of Sijilmassa and Aghmat, gold dinars were struck in Marrakesh already in 1092, announcing its debut as a city.[19] Unlike other Moroccan cities, Jews were not allowed to live within Marrakesh by decree of the Almoravid emir, but Jewish merchants from Aghmat visited Marrakesh routinely, usually via the Bab Aylan gate and a makeshift Jewish quarter was erected outside the city limits.[20] Intellectual life was more tentative. Although Malikite jurists and theologians closely connected to the Almoravid court moved to Marrakesh, there were no madrasas outside the palace, thus scholars were naturally more attracted to the vibrant intellectual centers of Fez and Cordoba, and even nearby Aghmat and Sijilmassa.[21] A leper colony, the walled village of El Hara, was established then or sometime after, to the northwest of the city.[16][22] The city's earliest Sufi saint, Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji ("Sidi Yussef Ben Ali", d.1197) was a leper.[21][23]

.png.webp)

Curiously, Marrakesh was originally unenclosed, and the first walls were erected only in the 1120s.[24] Heeding the advice of Abu Walid Ibn Rushd (grandfather of Averroes), Ali invested 70,000 gold dinars into bolstering the city's fortifications as Ibn Tumart and the Almohad movement became more influential.[25][26] 6 metres (20 ft) tall, with twelve gates and numerous towers, the walls were finished just on time for the first attack on the city by the Almohads.[27] The Almohads were a new religious movement erected by preacher and self-proclaimed Mahdi Ibn Tumart among the highland Masmuda of the High Atlas. They descended from the mountains in early 1130 and besieged newly fortified Marrakesh for over a month, until they were defeated by the Almoravids in the great Battle of al-Buhayra (al-buhayra means 'lake', referring to the irrigatated orchard gardens east of the city, where the battle took place). Nonetheless, the Almoravid victory was short-lived, and the Almohads would reorganize and capture the rest of Morocco, eventually returning to take the final piece, Marrakesh, in 1146.[28] After an eleven-month siege, and a series of inconclusive battles outside the city, in April 1147, the Almohads scaled the walls with ladders, opening the gates of Bab Dukkala and Bab Aylan, seizing the city and hunting down the last Almoravid emir in his palace. The Almohad Caliph Abd al-Mu'min refused to enter the city because (he claimed) the mosques were oriented incorrectly. The Almohads promptly demolished and razed all the Almoravid mosques so Abd al-Mu'min could make his entry.[29] Only the ablution fountain of Koubba Ba'adiyin remains of Almoravid architecture today, in addition to city's main walls and gates (though the latter have been modified many times).[30][31][32]

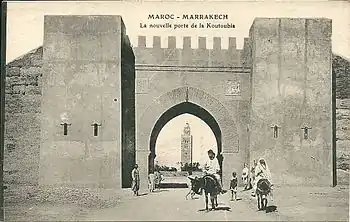

Although the Almohads maintained their spiritual capital at Tinmel, in the High Atlas, they made Marrakesh the new administrative capital of their empire, and erected much monumental architecture. On top of ruins of the Almoravid palace to the west, Abd al-Mu'min erected the (first) Koutoubia Mosque, although he promptly had it torn down shortly after its completion c. 1157 because of an orientation error.[33] The second Koutoubia mosque was probably finished by his son Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur c. 1195, with a grandiose and elaborately-adorned minaret that dominated the city's skyline.[32] Al-Mansur also built the fortified citadel, the Kasbah (qasba), just south of the city (medina) of Marrakesh, with the Bab Agnaou gate connecting them.[34] The Kasbah would serve as the government center of Marrakesh for centuries to come, enclosing the royal palaces, harems, treasuries, armories and barracks. It also included the a main mosque known as the Kasbah Mosque or El Mansouria Mosque (named after its founder) near Bab Agnaou.[32] Nothing, however, remains of the original Almohad palaces or al-Mansur's great hospital.[35]

The Almohads also expanded the waterworks with a wider irrigation system, introducing open-air canals (seguias), bringing water down from the High Atlas mountains through the Haouz plain.[36] These new canals allowed them to establish the magnificent Menara Garden and Agdal Gardens to the west and south of the city respectively.

Much of the Almohad architecture in Marrakesh had counterparts in the cities of Seville (which the Almohads chose as their regional capital in al-Andalus) and Rabat (which they raised from scratch). Artisans who worked on these edifices were drawn from both sides of the straits, and follow similar designs and decorative themes,[37] e.g. the Giralda of Seville and the (unfinished) Hassan Tower of Rabat are usually twinned with Koutobuia.[38] It was also under the Almohads that Marrakesh temporarily surged as an intellectual center, attracting scholars from afar, like Ibn Tufayl, Ibn Zuhr, Ibn Rushd, etc.[39]

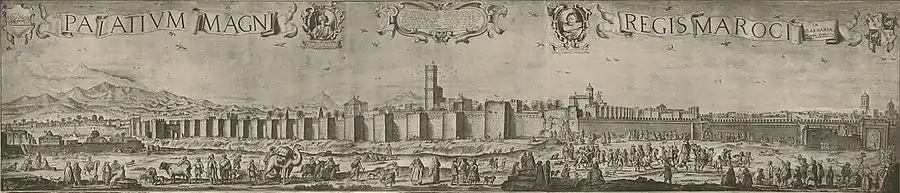

It was during Almoravid and Almohad times that Morocco received its name in foreign sources. Marrakesh was known in western Europe in its Latinized form "Maroch" or "Marrochio", and the Almohad caliphate was usually referred to in Latin sources as the "Kingdom of Marrakesh" (Regnum Marrochiorum).[40] Down to the 19th century, Marrakesh was often called "Morocco city" in foreign sources.[41]

The death of Yusuf II in 1224 began a period of instability. Marrakesh became the stronghold of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and the ahl ad-dar (descendants of Ibn Tumart), who sought to claw power back from the ruling Almohad family (the descendants of Abd al-Mu'min, who had their power base in Seville). Marrakesh was taken, lost and retaken by force multiple times by a stream of caliphs and pretenders. Among the notable events was the brutal seizure of Marrakesh by the Sevillan caliph Abd al-Wahid II al-Ma'mun in 1226, which was followed up by a massacre of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and their families and a public denunciation of Ibn Tumart's doctrines by the caliph from the pulpit of the Kasbah mosque.[42] After al-Ma'mun's death in 1232, his widow tried to install her son, acquiring the support of the Almohad army chiefs and Spanish mercenaries with the promise to hand Marrakesh over to them for the sack. Hearing of the terms, the people of Marrakesh hurried to strike their own deal with the military captains and saved the city from destruction with a hefty cash payoff of 500,000 dinars.[42]

Regional capital

The internal Almohad struggle led to the loss of al-Andalus to Christian Reconquista attacks, and the rise of a new dynasty, the Marinids in northeast Morocco. A Zenata clan originating from Ifriqiya, the Marinids arrived in Taza in the 1210s.[43] The Marinids ascended by sponsoring different Almohad pretenders against each other, while gradually accumulating power and conquering the north for themselves. By the 1260s, the Marinids had reduced the Almohads to the southern districts around Marrakesh.

The Marinid emir Abu Yusuf Yaqub laid his first siege of Marrakesh in 1262, but it failed. He thereupon struck a deal with Abu Dabbus, the cousin of the Almohad caliph, to conquer it for them. Abu Dabbus captured Marrakesh in 1266, but refused to hand it over to the Marinids, forcing Abu Yusuf Yaqub to come down and lay siege to it himself. The Marinids finally captured the city in September 1269.[44] The Almohad remnant retreated to the Atlas stronghold of Tinmel and continued putting up resistance until they were finally defeated in 1276.[45]

The Marinids decided against moving their court to Marrakesh and instead established their capital at Fez in the north. Toppled from its high perch, Marrakesh ceased to be an imperial capital, and thereafter served merely as a regional capital of the south. It suffered from relative neglect, as the Marinids expended their energies on embellishing Fez and other northern cities.[46]

Although the Almohads were extinguished as a political and military force, their old mahdist religious doctrines lingered, and Marrakesh remained a hotbed of heresy in the eyes of the orthodox Sunni Marinids.[47] Marinid emir Abu al-Hasan erected a couple of new mosques, notably the Ben Saleh Mosque (1331).[48] Abu al-Hasan also erected Marrakesh's first madrasa in 1343/9 [49] This was part of a general effort by the Marinids to reimpose Sunnism and restore Malikite jurisprudence to the position of prominence in Morocco it had previously enjoyed under the Almoravids.[47]

Marrakesh did not accept its eclipse gracefully, and repeatedly lent itself as a base for rebellions against the Marinid rulers in Fez. The harbinger was the great 1279 revolt of the Sufyanid Arabs who had recently arrived in the region, which was crushed with difficulty by the Marrakesh governor, Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Muhalli, a Marinid client chieftain.[50] The Marinids subsequently used Marrakesh as a training ground for the heirs to the throne, to hone their governing skills.[51] The use of the title khalifa ("successor") to denote the office of the governor of Marrakesh, came into usage as a result. But the grandeur of the old imperial capital repeatedly encouraged the young princes to aim higher. The very first trainee, Abu Amir, was barely a year in office before he was encouraged by the Marrakeshis to rebel in 1288 against his father, the emir Abu Yaqub Yusuf.[51][52] After Abu Yaqub's death in 1307, the new Marrakesh governor, Yusuf ibn Abi Iyad, rebelled against his cousin, the Marinid emir Abu Thabit Amir, and declared independence.[51] In 1320, it was the turn of Abu Ali, the son and heir of Abu Sa'id Uthman II, who rebelled and seized Marrakesh.[53] Roles were reversed during the sultanate of Abu Al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman, when the heir Abu Inan rebelled in Fez in 1349, and the ruling sultan fled to Marrakesh, and made that his base.[54]

Abu Inan's own son and heir, al-Mu'tamid ruled Marrakesh practically independently - or, more accurately, Marrakesh was effectively ruled by Amir ibn Muhammad al-Hintati, the high chief of the Hintata of the High Atlas (one of the old Almohad Masmuda tribes). Al-Hintati dominated the surrounding region, brought the Marinid heir in Marrakesh under his thumb, and arranged a modus vivendi with the sultan Abu Inan.[51][55] Al-Hintati remained master of the south after the death of Abi Inan in 1358, when the Marinid state fell into chaos, and the power was fought over between a series of palace viziers in Fez. After central powers was recovered by the new Marinid sultan Abd al-Aziz I, al-Hintati went into open rebellion in 1367 but was eventually defeated in 1370 and Marrakesh re-annexed.[51][56]

Chaos returned after the death of Abd al-Aziz I in 1372. The Marinid empire was effectively partitioned in 1374 between Abu al-Abbas ibn Abi Salim in Fez and his cousin Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Ifellusen in Marrakesh. But the two rulers quarreled and by 1382, Abu al-Abbas defeated his rival and reconquered Marrakesh.[51][57] The historical record thereafter is obscure, but it seems after a period of tranquility under Abu Abbas until 1393, Marrakesh and the surrounding region became effectively a semi-independent state in the hands of powerful regional governors (probably Hintata chieftains again), only nominally subject to the Marinid sultan in Fez.[51][58]

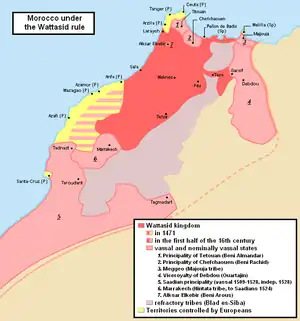

In 1415, the Christian Kingdom of Portugal launched a surprise attack and seized Ceuta, the first of a series of incursions by expansionary Portugal into Morocco that would mark much of the next century. Although effectively independent under Hintata emirs, Marrakesh is known to have participated in campaigns led by the sultans of Fez against the Portuguese invaders at Ceuta (1419) and Tangier (1437).[59] Following the failure to recover Ceuta, the Marinid emir was assassinated in 1420 and Morocco fragmented again. The Wattasids, a related noble family, seized power in Fez and ruled as regents and viziers on behalf of the Marinid child-sultan Abd al-Haqq II, but their authority did not really extend much beyond Fez, and Marrakesh remained virtually independent (certainly after 1430) in the hands of Hintata emirs.[51][60]

Sufism had arrived in the Maghreb and local Sufi marabouts arose to fill the vacuum of declining Marinid central power. At least two main branches of Sufi maraboutism can be identified:- the Shadhiliyya (strong in Marrakesh, the Sous, the Rif and Tlemcen), was more radical and oppositional to the established Marinid-Wattasid authorities, while the Qadiriyya (influential in Fez, Touat, Algiers and Bougie) was more moderate and cooperative.[61] Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli ("Sidi Ben Slimane"), a Sufi Shadhili imam from the Sous, catapulted to prominence in the mid-15th century. Being a sharif (i.e. a descendant from the family of the Prophet Muhammad), Imam al-Jazuli rode a wave of nostalgia for the 9th-century sharifian Idrisids, whose popular cult had recently been revived, partly as a contradistinction to the unpopular Marinids-Wattasids.[62]

In 1458, Marinid emir Abd al-Haqq II finally cleared out his powerful Wattasid viziers, who had dominated the palace of Fez for nearly forty years. The Hintata chiefs of Marrakesh promptly broke off into open revolt and the country took a decided turn towards the Sufi marabouts. It is reported that al-Jazuli, at the head of 13,000 followers from the Sous, crossed over the Atlas and established Sufi zawiya all over the country, a score of them in Marrakesh alone.[63] The assassination of Imam al-Jazuli in 1465 by Marinid agents led to an uprising in Fez which finally brought the Marinid sultanate to an ignominious end. A new wave of anarchy followed. The prospects of turning Morocco into a Sufi republic was interrupted by the return of the Wattasids, who seized power in Fez by 1472, this time installing themselves as sultans, but they were unable to exert their power much beyond the environs of Fez.[64] The Hintata emirs in Marrakesh were similarly confined, the bulk of the south crumbling into the hands of local Sufi marabouts.[65]

The Portuguese availed themselves of the fragmentation to increase their encroachments on Morocco territory, not only in the north (e.g. in Asilah and Tangier, 1471), but also seizing more southerly enclaves, along the Atlantic coast of Morocco, directly threatening the putative kingdom of Marrakesh. The Portuguese established themselves in Agadir (Santa Cruz no Cabo do Gué) in 1505, Souira Guedima (Aguz) in 1507 and Safi (Safim), in 1508. They subsequently seized Azemmour (Azamor) in 1513 and erected a new fortress nearby at Mazagan (Magazão, now al-Jadida) in 1514. From Safi and Azemmour, the Portuguese cultivated the alliance of local Arab and Berber client tribes in the surrounding region, notably a certain powerful Yahya ibn Tafuft. The Portuguese and their allies dispatched armed columns inland, subjugating the region of Doukkala and soon encroaching on Marrakesh.[66] By 1514, the Portuguese and their clients had reached the outskirts of Marrakesh and forced Nasir ibn Chentaf, the Hintata ruler of the city, to agree to tribute and allow the Portuguese to erect a fortress in Marrakesh.[67] However, the agreement was not carried out, so the next year (1515) the Portuguese and their Moorish allies returned at the head of a strong army, aiming to seize Marrakesh directly, but their army were defeated in the outskirts by a new force that had rather suddenly appeared from the south: the Saadian sharifs.[68]

Saadian capital

The Saadians were a widely respected sharifian family of the Draa valley. The head of the family, Abu Abdallah al-Qaim, was invited c. 1509-10 by the Sufi brotherhoods of the Sous valley to lead their jihad against the Portuguese intruders.[69] Al-Qaim led a celebrated campaign against the advanced posts of Portuguese Agadir and was soon recognized as leader in Taroudannt in 1511, receiving the allegiance of the tribes of the Sous. At the invitation of the Haha Berbers of the western High Altas, in 1514, al-Qaim moved to Afughal (near Tamanar), the shrine of the late sharif al-Jazuli and spiritual headquarters of the Shadhili branch of the Sufi marabout movement.[70] That same year, al-Qaim's jihad received the blessings (and a white banner) from the Wattasid emir of Fez.[71]

From Afughal, al-Qaim and his sons directed operations against Portuguese-held Safi and Azemmour. Initially poorly armed, the Saadian sharifs' military organization and strength improved with time. It was they who saved Marrakesh from the Portuguese attack of 1515. In 1518, the Sharifians finally defeated and killed the formidable client Yahya ibn Tafuft, soon followed by two of the Portuguese commanders. Via marabout networks among coastal tribes, from the Sous to Rabat, the Sharifians organized permanent, if loose, sieges around the Portuguese fortresses, cutting off their supplies and hampering their military operations. By the 1520s, the Portuguese had lost their sway over the outlying districts and were reduced to their fortresses.[72]

Marrakesh, like many other Moroccan cities, suffered greatly during this period, and it is reported that much of the city was depopulated as a result of the famines of 1514 and 1515, provoked by the military disorders in the countryside, the drought of 1517 and a series of failed harvests in 1520, 1521 and 1522.[73] The state of Marrakesh around this time was described by the eyewitness traveller Leo Africanus in his Descrittione dell’ Africa.[74] He notes how "a great part of this city, lies so desolate and void of inhabitants, that a man cannot without great difficulty pass, by reason of the ruins of many houses lying in the way...scarcely is the third part of this city inhabited", and how the grand palaces, gardens, schools and libraries of Marrakesh were "utterly void and desolate", given over to wildlife.[75] Nonetheless, the Saadian Sharifs deployed the organized networks of Sufi brotherhoods of the south to provide widespread food relief, and as a result attracted hungry migrants from the north. This effort elevated the reputation of the Saadians accordingly.[67][76]

Al-Qaim died in 1517, and his son Ahmad al-Araj took over the Saadian leadership. He moved to Marrakesh at the invitation of the Hintata ruler Muhammad ibn Nasir, to better direct operations. Tiring of his host (and father-in-law), al-Araj seized the Kasbah and killed the Hintata emir in 1524. Al-Araj made Marrakesh the new Saadian capital, assigning Taroudannt and the Sous to his younger brother, Muhammad al-Sheikh.[67][77] It was al-Araj who arranged for the translation of the remains of his father al-Qaim and the imam al-Jazuli from Afughal to Marrakesh.[78]

The new Wattasid sultan Ahmad al-Wattasi of Fez was not pleased by the turn of events, and in 1526 led a large army south to conquer Marrakesh. But the effort failed and the Wattasid attacks were repulsed. After an inconclusive battle, they agreed to the 1527 Treaty of Tadla, whereby Morocco was partitioned roughly along the Oum Er-Rbia River between the Wattasids of Fez in the north and the Saadians of Marrakesh in the south.[79] This arrangement did not last long - the truce broke down in 1530 and again in 1536 and another major battle was fought near Tadla, this time the Saadians coming off the better of it. However, mediation by the Sufi brotherhoods and religious jurists of Fez restored the partition and turned attention back on the Portuguese enclaves.[80]

Relations between the Saadian brothers began to splinter shortly after, and in 1540-41 they led two separate sieges - Ahmad al-Araj against Azemmour, Muhammad al-Sheikh against Agadir.[81] Al-Araj's siege failed, but Muhammad al-Sheikh captured Agadir in 1541, an event which provoked Portuguese evacuation elsewhere, and the Saadian recovery of Safi and Azemmour the very next year (1542). The victory elevated the prestige and ambitions of Muhammad al-Sheikh, who promptly challenged and defeated his brother, taking over the leadership of the Sharifian movement, and driving Ahmad al-Araj to exile in Tafilelt.[82] Upon seizing Marrakesh, the autocratic-minded Muhammad al-Sheikh expelled the Sufi sheikhs, his brother's erstwhile allies, from the city.[83]

Muhammad al-Sheikh proceeded to invade Wattasid Fez in September 1544/5, defeating and capturing the sultan Ahmad al-Wattasi. But the religious jurists and the Qadiri marabouts, strong in Fez, refused him entry into the city.[84] Muhammad al-Sheikh was forced to lay siege and finally conquered the city by force in September 1549. The Saadians proceeded to advance east and annex Tlemcen in 1550.[85]

The Saadian success roused the intervention of the Ottoman Turks who had recently established themselves in nearby Algiers and had been seeking to extend their influence further west.[86] When the Saadian sharif proved deaf to their overtures, the Ottomans threw their considerable weight behind his enemies. With Ottoman assistance, in early 1554, the exiled Wattasid vizier Abu Hassan was installed in Fez. They also persuaded the deposed Saadian brother Ahmad al-Araj to launch a campaign from Tafilalet to recover Marrakesh. Muhammad al-Sheikh rallied and defeated his brother outside of Marrakesh, before turning north and reconquering Fez by September 1554.[87] To keep the Ottomans at bay, the Saadians struck up an alliance with the Kingdom of Spain in 1555. Nonetheless, Ottoman agents assassinated Muhammad al-Sheikh in 1557. The transition to his son and successor, Abdallah al-Ghalib was not smooth. Ottoman agents intrigued with his brothers - who were driven into exile. The Turks went on the offensive, capturing Tlemcen and invading the Fez valley in 1557. Al-Ghalib only just managed to fend off the Turkish attack at the Battle of Wadi al-Laban in 1558. The vulnerability of Fez to incursions from Ottoman Algeria prompted the Saadians to retain their court in safer Marrakesh rather than relocate to Fez. Thus, after over two centuries of interlude, Marrakesh was restored as the imperial capital of unified Morocco, and Fez demoted to a secondary regional capital of the north.[88]

The Saadians faced difficulties legitimizing their rule. As sharifs, descendants of Muhammad, they claimed to stand above the ulama (religious jurists) and the Ottoman caliph. But the Saadians had no secure tribal basis, their ascendancy had been consistently opposed by the Maliki religious jurists and the rival Qadiri branch of Sufi marabouts, and many questioned their claims of sharifian ancestry and their jihadist credentials (in light of the Spanish alliance).[89] The Saadians responded to these doubts in "the language of monuments", their showpiece: Marrakesh.

Starting with Abdallah al-Ghalib, the Saadians revived and embellished Marrakesh into a magnificent imperial city, a monument unto their own royal majesty, to rival the splendor of Ottoman Constantinople. Their great vanity project was the complete reconstruction of the old Almohad Kasbah as their royal city, with new gardens, palaces, barracks, a refurbished El-Mansuria Mosque and (later) their necropolis, the Saadian Tombs on the south side of the mosque. They refurbished the Ben Youssef Mosque and, to raise their own stable of jurists to rival Fez, founded the great new Ben Youssef Madrasa in 1564–65, the largest in the Maghreb at the time (and not a mere refurbishment of the old Marinid madrasa of Abu al-Hasan).[90] The Saadians erected several new mosques, notably the Bab Doukkala Mosque (1557–1571) and the Mouassine or al-Muwassin Mosque (1562–72).[91][92]

The city's layout was redesigned: the city center refocused away from the Ben Youssef Mosque and re-centered at the Koutoubia Mosque further west.[93] The Jewish district (the Mellah, literally the "salted place") was established c. 1558 just east of the Kasbah.[94] The influx of Moriscoes, following their expulsion from Spain in the early 17th century led to the establishment of a dedicated quarter of Orgiba Jadida.[95] The Saadians erected pilgrimage shrines to two of the major Sufi saints - the Zawiya of Sidi Ben Slimane al-Jazuli (c. 1554), founder of the 15th-century Shadhili Sufi brotherhood whose remains were translated from Afughal, and the Zawiya of Sidi Bel Abbas al-Sabti (c. 1605), the patron saint of Marrakesh (other Sufi shrines were built later, and most were restored or modified several times after this).[21][92][96]

Following the death of al-Ghalib in 1574, the Saadians entered into a dynastic succession conflict, provoking Portuguese intervention.[97] After a celebrated victory over the Portuguese king at a 1578 battle at Ksar el-Kebir, the new Saadian ruler, Ahmad al-Mansur (r.1578-1603), continued al-Ghalib's building program in Marrakesh, and took Saadian pretensions to a new height, earning him the appellation al-Dhahabi ("the Golden"). He abandoned the Kasbah and erected a new sumptuous residence for himself, the El Badi Palace (meaning "the Splendid" or "the Incomparable", an enlarged version of the Alhambra in Granada). He raised a professional standing army, adopted the caliphal title of 'al-Mansur', and emulated the ornate ceremonial magnificence of the Ottoman court (including speaking to courtiers only from behind a curtain).[98] Al-Mansur initially financed his extravagances with the ransoms of Portuguese prisoners and heavy taxation. When these wore out, and the populace began simmering, al-Mansur seized control of the trans-Saharan trade routes and went on to invade and plunder the gold-saturated Sudanese realm of the Songhai Empire in 1590–91, bringing Timbuktu and Djenné temporarily into the Moroccan empire.[99]

Things soon began to fall apart. A nine-year plague enveloped Morocco in 1598–1607, weakening the country tremendously, and taking al-Mansur in 1603.[100] His successor Abu Faris Abdallah was acclaimed in Marrakesh, but the jurists of Fez elevated his brother Zidan al-Nasir instead. Zidan managed to prevail and entered Marrakesh in 1609. But now another brother, Muhammad al-Sheikh al-Ma'mun revolted in the north, and soon Zidan was reduced to Marrakesh.[101] As Saadian power buckled, Morocco fell into anarchy and fragmented into smaller pieces for much of the next century. Zidan was driven out of Marrakesh by a religious leader, the self-proclaimed mahdi Ahmed ibn Abi Mahalli in 1612, and was restored only in 1614 with the assistance of another religious leader, Yahya ibn Abdallah, a Sufi marabout from the High Atlas, who subsequently tried to exert his own power over the city from 1618 until his death in 1626. Zidan somehow found the time and resources during all this to complete the Saadian Tombs at the Kasbah Mosque. However, there were not enough resources to complete a grand Saadian mosque begun by Ahmed al-Mansur, slated to be called the Jemaa al-Hana ("Mosque of Prosperity"); local people soon began to call the unfinished site the Jemaa el-Fnaa (Mosque of the Ruins), what would become the future central square of Marrakesh.[102]

While the rest of Morocco was parcelled out to other parties, Marrakesh remained practically the sole citadel of a succession of irrelevant Saadian sultans, their small southern dominion extending only from the foot of the High Atlas to the Bou Regreg. The neighboring middle Atlas, Sous and Draa valleys were in the hands of rivals and marabouts, and the Atlantic coast in the hands of various local warlords and companies of Morisco corsairs. In 1659, the Shabana (Chebana, Shibanna, Shbanat), an Arab Bedouin tribe of Hillalian descent, once part of the Saadian army, seized control of Marrakesh and put the last Saadian sultan, Abdul al-Abbas, to death. Their qaid, Abd al-Karim ibn Abu Bakr al-Shbani declared himself the new sultan of Marrakesh.[103]

Alawite city

In the course of the 17th century, the Alawites, another sharifian family, had established themselves in Tafilalet (Sijilmassa region). After the death of the Alawite scion Ali al-Sharif in 1640, his son Muley Muhammad became the head of the family and expanded their dominance locally.[104] Around 1659, one of Muhammed's brothers, Muley al-Rashid was expelled from Tafilalet (or left on his own accord) and proceeded to wander around Morocco, eventually settling in Taza, where he quickly managed to carve out a small fief for himself.[105] Muley Muhammad, who had his own ambitions over the country, confronted his brother, but was defeated and killed outside Taza in 1664. Al-Rashid seized the family dominions of Talifalet and the Draa valley (which Muhammad had conquered in 1660). With these amplified bases, Muley al-Rashid had the wherewithal to launch a campaign of conquest over the rest of Morocco.

Al-Rashid started his campaign from Taza in the north and entered Fez in 1666, where he was proclaimed sultan. Two years later, he defeated the Dili marabouts that controlled the Middle Atlas. Muley al-Rashid proceeded south to capture Marrakesh in 1669, massacring the Shabana Arabs in the process.[106] He then proceeded down into the Sous, conquering it by 1670, thereby reunifying Morocco (save for the coastal areas, which would take a little longer). Al-Rashid is usually credited for the erecting the shrine and mosque of Qadi Iyad ("Cadi Ayyad") in Marrakesh, where the remains of his father, Ali al-Sharif, stem of the Alawite dynasty, were translated. Two later Alawite rulers (Moulay Suleiman and Muhammad IV) would choose be buried here as well.[107]

On al-Rashid's death in April 1672, Marrakesh refused to swear allegiance to his brother and successor Ismail Ibn Sharif, who had served as vice-roy in Fez. Instead, Marrakeshis opted for his nephew Ahmad ibn Muhriz.[108][109] Ismail promptly marched south, defeated Ahmad and entered Marrakesh in June 1672. But Ibn Muhriz escaped and fled to the Sous, from whence he would return in 1674, take Marrakesh back and fortify himself there. Ismail was forced to return and lay a two-year siege on the city. Marrakesh finally fell to assault in June 1677, and this time Muley Ismail took his revenge on the city, giving it over to the sack.[109][110] Ibn Muhriz, however, had escaped to the Sous again and would try a few more times to recover it, until he was finally tracked down and killed in 1687.[109]

Ismail's punishment of Marrakesh did not end there. Ismail established his capital at Meknes, erecting his royal palaces there with materials stripped from the palaces and buildings of Marrakesh. Much of the Kasbah, lovingly built up by the Saadians, was stripped bare and left in ruins, as were most other Saadian palaces in the city. Al-Mansur's great al-Badi palace was practically dismantled and carted off to Meknes, the Abu al-Hasan Madrasa completely so.[109][111]

Nonetheless, Ismail's legacy in Marrakesh was not purely destructive. Ismail translated many tombs of Sufi saints in the region to Marrakesh, and erected several new shrines for them. Seeking to replicate the great pilgrimage festivals of Essaouira, Ismail requested the Sufi sheikh Abu Ali al-Hassan al-Yusi to select seven of them to serve as the "Seven Saints" (Sab'atu Rijal) of Marrakesh, and arranged a new pilgrimage festival. For one week in late March, the pilgrims have to visit all seven shrines in required order (roughly anticlockwise):[21][112] 1. Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji ("Sidi Yussef Ben Ali", d.1197), just outside the Bab Aghmat in the southeast, 2. Qadi Iyad ("Cadi Ayyad ben Moussa", d.1149), inside the Bab Aylan in the east, 3. Abu al-Abbas al-Sabti ("Sidi Bel Abbes", d.1204), by the Bab Taghzout in the north (note: the pilgrimage route from 2 to 3 passes usually outside the eastern city wall, and re-enters at Bab el-Khemis, in order to touch the shrines of Sidi el-Djebbab and Sidi Ghanem along the way, although they are not part of the Seven); from Bab Tahgzhout, the pilgrimage path heads straight south through the middle of the city, visiting in succession the shrines of 4. Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli ("Sidi Ben Slimane", d. 1465), just south the previous, 5. Abd al-Aziz al-Tabba ("Sidi Abdel Aziz el-Harrar", 1508), just west of the Ben Youssef Mosque, 6. Abdallah al-Ghazwani ("Sidi Mouley el-Ksour", d.1528), just below the al-Mouassine Mosque then exiting the city again, through the Bab al-Robb gate (west of the Kasbah) to reach the final shrine 7. Abd al-Rahman al-Suhayli ("Sidi es-Souheli", d.1185), outside the city to the southwest.

In 1699–1700, Ismail partitioned Morocco into lordships to be governed by his many sons. The experiment did not turn out too well, as several used their fiefs as a basis of revolt. One of these sons, Mulay Muhammed al-Alem, rose up in the Sous and seized Marrakesh, which had to be taken back again. In the aftermath, Ismail canceled the experiment and annexed all the lordships back.[113] Chaos returned after Moulay Ismail's death in 1727, and a succession of Alawite sultans followed by a series of coups and counter-coups, engineered by rival army factions, for the next couple of decades.[114] Marrakesh did not play too much of a role in these palace affairs. Abdallah ibn Ismail seized Marrakesh in 1750, placing it under his son Muhammad as vice-roy, who ruled it with remarkable stability while chronic anarchy reigned in the north. In 1752, the army offered Muhammad the crown of the whole in place of Abdallah, but he refused, letting his father reign until his death in 1757.[115]

.jpg.webp)

Upon his ascension, Muhammad III ibn Abdallah retained Marrakesh as preferred residence and de facto capital.[116] Neglected since Ismail's pillaging spree, Muhammad found much of the city, particularly the Kasbah, in ruins and reportedly had to live in his tent when he arrived. But he soon set to work.[117] He rebuilt the Kasbah almost from scratch, erecting the royal palace Dar al-Makhzen (Palais Royal, also known as the Qasr al-Akhdar, or "Green Palace", on account of its internal garden, the Arsat al-Nil, named after the Nile) and the Dar al-Baida ("White Palace") nearby, both on the ruins of old Saadian palaces. Muhammad established four estates within Marrakesh for each of his sons, as a gift for when they came of age - the arsats of al-Mamoun, al-Hassan, Moussa and Abdelsalam. Muhammad III also expanded the walls of Marrakesh the north by the Bab Taghzut, to include the formerly suburban mosque and shrine of patron Sidi Bel Abbas al-Sabti, incorporating it as a new city district.[118] Much of the modern medina of Marrakesh is owed to how Muhammad III re-built it in the late 18th century.

Crisis followed Muhammad III's death in 1790. The succession of his son Yazid, whose cruel reputation preceded him, was disputed and Marrakeshis instead acclaimed his brother Hisham. Yazid marched on and recovered Marrakesh, putting it through a violent sack,[109] but he was killed by Hisham's counterattack. Fez declined to recognize Hisham, and opted for another brother, Suleiman (or Slimane) while Marrakesh itself divided its loyalties, part of it opting for Hisham, another part acclaiming another brother Hussein.[109] Suleiman bided his time, while Hisham and Hussein fought each other to exhaustion. Marrakesh finally slipped into Suleiman's hands in 1795.[109][119]

The plague hit Marrakesh again in 1799, heavily depopulating the city.[120] Nonetheless, it was maintained by Suleiman as his primary residence and capital. He completely rebuilt the Ben Youssef Mosque, not a trace remaining of its old Almoravid and Almohad design. Driven out of Fez, Suleiman was defeated just outside Marrakesh in 1819, in an uprising by the Cherarda (an Arab Bedouin army tribe from the Gharb), although his person was preserved and delivered safely. After Suleiman's death in 1822, his successor Muley Abd al-Rahman reopened trade with foreign nations. Marrakesh hosted numerous foreign embassies seeking out trade treaties with the new Alawite sultan - e.g. Portugal in 1823, Britain in 1824, France and Sardinia in 1825.[121] Abd al-Rahman is principally responsible for reforesting the gardens outside of Marrakesh.

The 19th century saw increasing instability and the progressive encroachment of European powers on Morocco. The French conquest of Algeria began in 1830. Moroccan troops were rushed up to defend Tlemcen, which they considered part of their traditional sphere, but the French captured Tlemcen in 1832 and drove the Moroccans out. Abd al-Rahman supported the continued guerilla resistance in Algeria led by Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri. The French attacked Morocco directly in 1844, and forced a humiliating defeat on Abd al-Rahman. By this time, the internal situation in Morocco was already unstable, with army units across the north and east basically ungovernable, famine once again rocked Morocco. Abd al-Rahman's successor, Mohammed IV of Morocco was confronted immediately by the Spanish War of 1859-60 and yet another humiliating treaty. While the sultan was busy dealing with the Spaniards in Ceuta, the Rehamna tribe in the south rebelled and laid a tight siege on the city of Marrakesh, which was broken by Muhammad IV only in 1862.[109]

Muhammad IV and his successors Hassan I and Abd al-Aziz moved the court and capital back to Fez, demoting Marrakesh once again to a regional capital under a family khalifa.[109] Nonetheless, Marrakesh was still visited periodically, and numerous new buildings were erected, most notably the late 19th-century palaces of various leading courtiers and officials. The Bahia Palace ("the Brilliant") was built in the 1860s as the residence of Si Musa, a palace slave and grand vizier of Muhammad IV and Hassan I. It was used as a residence by Si Musa's son and successor Ahmed ibn Musa ("Ba Ahmed"), who served as the grand vizier of Abd al-Aziz. Other Alawite palaces of this era include the Dar Si Said (now the Museum of Moroccan Art), built by Ba Ahmed's brother, Si Said ibn Musa, the Dar Menebbi (now the Musée de Marrakech) built by the Tangier noble and war minister Mehdi el-Menebbi and the early 20th-century palace of Dar el Glaoui, residence of the pasha Thami El Glaoui. The late 19th century also saw the erection of many new religious buildings, such as the Sufi shrine of Sidi Abd al-Aziz and the mosques of Sidi Ishaq, Darb al-Badi, Darb al-Shtuka, Dar al-Makzhen and Ali ibn Sharif.[122]

With the arrival of increasing European influence - cultural as well as political - in the Alawite court in Fez, Marrakesh assumed its role as opposition center to Westernization.[102] Until 1867, individual Europeans were not permitted to enter the city unless they acquired special permission from the sultan.[123]

The colonial encroachment had led to a shift in the traditional relationship between the "Makhzen" (Alawite sultan's government) and the semi-autonomous rural tribes. To extract more taxes and troops from them, the Alawite sultan began directly appointing lords (qaids) over the tribes - a process that accelerated in the 1870s with the loss of customs revenues in Moroccan ports to colonial powers after 1860.[124] Initially a centralizing move, these appointed qaids, once ensconced in their tribal fiefs, proved to be more difficult to control than the old elected tribal leaders had been. In the late 19th century, Madani al-Glawi ("El Glaoui"), the qaid of Telouet, armed with a single 77m Krupp cannon (given to him by sultan Hassan I in 1893), managed to impose his authority over neighboring tribes of the High Atlas and was soon exerting his dominance on the lowlands around the city of Marrakesh, half-in-alliance, half-in-rivalry, with two other great High Atlas qaids, Abd al-Malik al-Mtouggi (al-Mtugi), who held the Atlas range southwest of al-Glawi, and Tayyib al-Goundafi (al-Gundafi), to the northeast of him.[125] The largest regional tribe was the Rehamna, an offshoot of the Maqil Arabs, who held much of the lowland plain of Haouz and the upper Tensift, and constituted as much as a third of the population of Marrakesh itself.[126] The High Atlas lords exerted their influence over the Rehamna tribe via their two major chieftains, the El Glaoui-allied al-Ayadi ibn al-Hashimi and the Mtouggi-allied Abd al-Salam al-Barbushi.[127]

Hafidiya

.jpg.webp)

After the death in May 1900 of the grand vizier Ahmed ibn Musa ("Ba Ahmed"), the empire's true regent, the young Alawite sultan Abd al-Aziz tried to handle matters himself. But the teenage sultan, who preferred to surround himself with European advisors, was unduly susceptible to their influence and soon alienated the population.[128] The country careened into the throes of anarchy, tribal revolts and plots of feudal lords, not to mention European intrigues. Unrest mounted with the devastating famine in 1905–1907, and the humiliating concessions at the 1906 Algeciras Conference.[129] The Marrakesh khalifa Abd al-Hafid was urged by the powerful southern qaids of the High Atlas to lead a revolt against his brother Abd al-Aziz (then based in Rabat, Fez being divided). The unrest had been accompanied by a spasm of violent xenophobia, which saw the lynching of several European residents in Tangier, Casablanca and Marrakesh. Dr. Émile Mauchamp, a French doctor suspected of spying for his country, was murdered in Marrakech by a mob in March 1907.[130] This gave France the pretext for more direct intervention. French troops occupied Oujda in March 1907, and, in August 1907, bombarded and occupied Casablanca. The French intervention pushed the revolt forward, and Marrakeshis acclaimed Abd al-Hafid as the new sultan on 16 August 1907.[131] Alarmed, Abd al-Aziz sought out the assistance from the French in Casablanca, but that only sealed his fate. The ulama (religious jurists) of Fez and other cities promptly declared Abd al-Aziz unfit to rule and deposed him permanently by January 1908.[132] In June, Abd al-Hafid personally went to Fez to receive the city.[133] Abd al-Aziz finally reacted, gathered his army and marched on Marrakesh in the summer of 1908. But discontent was rife, and much of his army deserted along the way, with the result that Abd al-Aziz was easily and decisively defeated by the Hafidites in a battle at Bou Ajiba outside Marrakesh on 19 August 1908. Abd al-Aziz fled and abdicated two days later.[134]

In reward for their assistance, sultan Abd al-Hafid appointed Madani al-Glawi as his grand vizier, and his brother Thami al-Glawi as the pasha (governor) of Marrakesh. Despite his victory, Abd al-Hafid's position was hardly enviable, given the French military and financial noose. Imperial Germany and Ottoman Turkey, interested in increasing their influence, had offered their support to Abd al-Hafid to get rid of the French, but direct French pressure made Abd al-Hafid even more dependent. Foiled, the Germans switched their attentions to the southern Morocco, and cultivated their influence there, striking several informal agreements with various southern lords. Notable among these was the Saharan marabout Ma al-'Aynayn, who had led the anti-French resistance in Mauritania in the early 1900s. He had moved north and was part of the coalition that brought Abd al-Hafid to power in 1909. Encouraged by the Germans, the very next year, al-Aynayn proclaimed his intent to drive the French out of Morocco but he was defeated by French general Moinier at Tadla (northeast of Marrakesh) in June 1910 and was forced to retreat to Tiznit, in the Souss valley, where he died shortly after.[135]

Facing financial difficulties and foreign debt problems, Abd al-Hafid and El Glaoui imposed new heavy taxes, which set the country simmering. In return for a new French loan, Abd al-Hafid was forced to capitulate to the Franco-Moroccan accords in March, 1911, which enlarged the tax and property privileges of French expatriates, ratified French administration of the occupied Oujda and Chaouia regions, and even indemnified them for their military expenses.[136] The accords were received with widespread dismay in Morocco. An uprising in Fez had to be put down with the assistance of French troops and Abd al-Hafid was forced to dismiss the El Glaoui brothers from their posts in June 1911.[137] The entry of French troops alarmed other European powers. Spanish troops quickly expanded their territorial enclave in the north, while Germany dispatched a gunboat to Agadir (see Agadir Crisis).[138] At the height of the crisis, the dismissed El Glaoui brothers approached German diplomats in Essaouira offering to detach southern Morocco, with Marrakesh as its capital, and turn it into a separate German protectorate.[139] But the offer was rebuffed, as a French-German accord was about to be signed in November 1911 resolving the Agadir crisis.

French protectorate

.jpg.webp)

The resolution of the Agadir crisis cleared the way for the Treaty of Fez on March 30, 1912, imposing a French Protectorate on Morocco. General Hubert Lyautey was appointed the first French Resident-General of Morocco.[140] The news was received with indignation, the Moroccan army mutinied in mid-April and a violent popular uprising in Fez erupted.[141] A new column of French troops managed to occupy Fez in May, but events were already in motion - the tribesmen of the north were set aflame and the French colonial forces were spread out and besieged along the thin line from Casablanca to Oujda. Changing course, the sultan Abd al-Hafid entered into contact with the rebels, prompting the French general Lyautey to force him to abdicate on 11 August, in favor of his more amenable brother, Yusuf (at the time, the pasha of Fez), who was promptly escorted to the relative safety of Rabat under French guard.[142]

Discontent in the south gathered around Ahmed al-Hiba, nicknamed the "Blue Sultan", son of the late al-Aynan, whose forces were still gathered at Tiznit in the Souss valley. Proclaiming the Alawites had failed in their duty, al-Hiba proposed to cross over the Atlas and establish a new southern state based in Marrakesh, from which he would go on to drive the French out of the north.[143] Despite al-Hiba's denunciation of the quasi-feudal system of grand qaids, some of the southern lords, who had previously enjoyed German patronage and balked at the prospect of French-northern dominance, lent their military support to al-Hiba's bid.[144] With the assistance of the qaids Haida ibn Mu'izz of Taroudannt and Abd al-Rahman al-Guellouli of Essaouira, the Hibists quickly gained possession of the Sous valley and the Haha region.[145] Al-Hiba promptly gathered up his Saharan and Soussian tribesmen and began his march over the High Atlas in July, 1912. Although the High Atlas lords considered stopping him, Hibist fever had gripped the rank-and-file of their tribes, and they did not dare oppose al-Hiba or risk being overthrown themselves. Al-Hiba's passage over the High Atlas was facilitated by the qaid al-Mtouggi. In August, 1912, hearing of the abdication of Abd al-Hafid, al-Hiba declared the throne vacant and was acclaimed by his followers as the new sultan of Morocco at Chichaoua, in the outskirts of Marrakesh.[146] The Mtouggi-allied pasha of Marrakesh, Driss Mennou handed Marrakesh over to al-Hiba on 15 August.[147]

The rise of a new sultan in Marrakesh alarmed Lyautey. Although Paris contemplated a power-sharing arrangement that might allow al-Hiba to remain sultan of Marrakesh and the south, Lyautey was sufficiently aware of Moroccan history to consider that unsustainable.[148] Lyautey tried what he could to delay al-Hiba's advance and prevent Marrakesh from falling. Through the private channels of the Marrakeshi banker Joshua Corcus, Lyautey entered into communication with the El Glaoui brothers, Madani and Thami.[148] In the political wilderness since their dismissal in early 1911, the El Glaoui brothers sensed their handling of al-Hiba could serve as their ticket back to the top. They were unable to prevent the Hibists from taking Marrakesh and, pressed by them, Thami El Glaoui surrendered five of the six French officials residents in the city over to al-Hiba (retaining one for himself, to serve as a witness of his actions to the French authorities).[149] Nonetheless, the El Glaoui brothers steadily fed the French authorities updates on the situation in Marrakesh and used their personal influence to lure wavering qaids away from the Hibist cause.[148]

Deeming it the priority threat to the French protectorate, Lyautey peeled away French colonial soldiers from their hard-pressed positions in the north to assemble a new column, under the command of Colonel Charles Mangin, and promptly set them out to take Marrakesh. Mangin's column met the Hibist army at Battle of Sidi Bou Othman (6 September 1912).[150] Modern French artillery and machine guns practically massacred al-Hiba's poorly equipped army of partisans. Seeing the writing on the wall, most large lords - al-Mtouggi, Driss Menou, al-Goundafi even Haida al Mu'izz - had switched sides and abandoned al-Hiba, some before the battle, others immediately afterwards.[151] As Mangin approached the city, on 7 September, the qaids, led by El Glaoui, pounced inside it, their loyalists overwhelming the Hibist garrisons, seizing hold of the hostages and driving al-Hiba and his remaining partisans out of Marrakesh. Having restored order inside the city, the qaids allowed the French column under Mangin to enter and take possession of Marrakesh, nominally in the name of sultan Yusuf, on 9 September 1912.[152] Thami El Glaoui was promptly restored to his former position as pasha of Marrakesh and awarded the Legion of Honour by Lyautey, who visited Marrakesh in October, 1912.

The region around Marrakesh was organized as a military district, initially under Mangin, but given the lack of French troops, Lyautey's policy was to rely on the grand qaids - al-Glawi, al-Mtouggi, al-Goundafi, al-Ayadi, Haida, etc. - to hold the south in their name.[153] El Glaoui and al-Goundafi proved their worth almost immediately, invading the Souss and driving the Hibists out of Taroudannt, forcing them up the mountains.[149] Leopold Justinard organized a French column from Marrakesh in 1917 to put an end to the Hibist threat, but they faced such fierce resistance in the mountains, they were unable to make much headway.[154] The Anti-Atlas, as well as other hard-to-access regions, would remain out of French hands for a while. Upon the death of Madani al-Glawi in 1918, Lyautey ignored the opportunity to chop away at the Glawi clan's power, characterized as increasingly tyrannical and unsavory by many other French officials, and instead promoted Thami's bid at the head of the Glawi clan and the undisputed "Lord of the Atlas", above all others. As rival Atlas qaids al-Mtouggi and al-Gundafi faded, Thami El Glaoui's only real challenger was his own rabidly anti-French nephew, Si Hammu, the son of al-Madani, who had inherited the al-Glawi family mountain holdings in Telouet and defied all attempts to bring him to heel.[155]

As the French authorities deemed Marrakesh and Fez dangerously prone to revolt, the Moroccan capital was moved permanently to Rabat, leaving Marrakesh in the tight grip of Thami El Glaoui, who remained as pasha of Marrakesh throughout nearly the entire French Protectorate period (1912-1956). El Glaoui collaborated intimately with the French authorities and used his formal power over Marrakesh to acquire vast properties in the city and region, accumulating a personal fortune reportedly greater than the sultan's own.[156] El Glaoui's notorious corruption - he received a cut from practically every business in Marrakesh, including prostitution and drug-trafficking - was tolerated and almost even encouraged by the residents-general, for so long as had his hand in the till, El Glaoui had every incentive to maintain and prolong the state of affairs, making him a dependable client of the French authorities.[157]

In 1912, Marrakesh had 75,000 inhabitants, compactly contained in the Medina, the Kasbah and the Mellah, with city life centered around the Jemaa el-Fnaa.[158] European colonists soon began arriving in Marrakesh - some 350 had already taken residence in the city by March 1913[159] - and El Glaoui facilitated their entry with apportionments of land in the area. However, not all European visitors were thrilled. Edith Wharton, who visited Marrakesh in 1917 as Lyautey's guest, found the city "dark, fierce and fanatical" and while fond of its fine palaces, denounced the "megalomania of the southern chiefs" of Marrakech.[160]

Lyautey had grand plans for urban development, but he also wanted to conserve the artistic heritage and not touch the historic centers of Moroccan cities.[161] The French urban planner Henri Prost arrived in 1914 at Lyautey's invitation, and upon his instructions, set about planning a new modern city in the outskirts of Marrakesh, primarily for French colonists.[162] Taking the Koutoubia mosque and the Jemaa el-Fnaa as the central point for the whole, Prost directed the development of the new city (ville nouvelle) at what is now Gueliz in the hills northwest of Marrakesh. The church of St. Anne, the first proper Christian church in Marrakesh, was one of the first buildings erected in Gueliz.[163] Prost laid out a great road from Gueliz to Koutoubia, which became what is now Avenue Muhammad V, entering the Medina by Bab el-Nkob. Development of the new city took place in the 1920s. The Majorelle Garden in Gueliz was set up by Jacques Majorelle in the late 1920s.[164]

In 1928, south of Gueliz, Henri Prost began laying out the more exclusive quarter of l'Hivernage, destined as a haven for French diplomats and high officials wintering in Marrakesh (hence its name). It was kept separate from Gueliz by the el Harti gardens and a series of sports fields and complexes. Hivernage was laid out in the palm and olive groves along the road (modern Avenue de La Menara) that connected the old city (at Bab al-Jedid) with the Menara Garden in the west. The avenue was set parallel to the High Atlas to maximize the panoramic view of its peaks.[165] With the help of the architect Antoine Marchisio, Prost erected the luxurious La Mamounia hotel in 1929, in the gardens of the 18th-century arsat of al-Mamoun, elegantly melding Art Deco and Orientalist-Marrakeshi designs.[164][165] Winston Churchill, who first visited Marrakesh in 1935 and stayed at La Mamounia, considered it to be one of the best hotels in the world.[160] A casino was soon added. Hivernage, covered by grand villas and hotels, would become a winter destination for many French music-hall celebrities, such as Maurice Chevalier, Edith Piaf and Josephine Baker, and soon morph into the playground of American and European movie stars and a routine stop for the post-war jet set.[164][165] The old Atlas qaid, Thami El Glaoui welcomed the stream of celebrity guests, hosting parties for them in his palaces that are said to have been dripping with lavish excess.

Marrakesh, the launchpad of so many revolts in the past, was kept uncharacteristically subdued under El Glaoui's thumb. It was the north that simmered. The Rif War that erupted in 1919 in Spanish Morocco soon spilled over into the French Protectorate, threatening Fez. Lyuautey was critical of the counter-insurgency strategy directed by Madrid and Paris, feeling it important to reinforce the sultan's authority through native institutions.[166] Lyautey resigned in 1925, and was replaced by a series of more conventional residents-general.[167]

Sultan Youssef died in 1927, and was succeeded by his son Mohammed V of Morocco. Thami El Glaoui had a critical role in this selection, and maintained his absolute control over Marrakesh, which was now nominally under a new khalifa Moulay Driss, the eldest son of Youssef.[168] Young and powerless, Muhammad V offered little resistance to the French protectorate authorities at first. He put his signature to the notorious 1930 Dahir, separating Berbers from Arabs, and placing the former under the jurisdiction of French courts. This led to an eruption of anti-French nationalist feeling and led to the establishment of the Hizb el-Watani (Parti National) by young nationalist leaders like Allal al-Fassi, with cells in various cities, including Marrakesh.[169] After riots in Meknes in 1937, French authorities cracked down on the incipient nationalist movements and exiled their leaders. This period coincided with a series of French military campaigns that finally subdued lingering resistance in the farther corners and highlands of Morocco - the Middle Atlas (1931), the Tafilalet (1932), the Jebal Saghro (1933–34) and finally the Anti-Atlas (1934) were subjugated by French military campaigns.[170]

With the fall of France in 1940, during World War II, the French Protectorate of Morocco came under the jurisdiction of the Vichy regime, which installed its own residents-general. The sultan Muhammad V was not inclined to his new masters. Although generally powerless, the sultan refused Vichy demands when he could, including reportedly rejecting Vichy demands in 1941 to pass anti-Jewish legislation, claiming them inconsistent with Moroccan law.[171] Muhammad V welcomed the November 1942 Allied landings in Morocco, refusing Vichy instructions to move his court inland. Muhammad V hosted the Allied leaders Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, in the course of which Churchill lured Roosevelt on a side excursion to Marrakesh.[172] The Allied presence in Morocco encouraged the nationalist movements, who were brought under a new umbrella party, Hizb al-Istiqlāl (Independence Party) in 1943.[173] However, an Istiqlal petition to the Allied powers requesting a commitment to post-war independence for Morocco was used by the Free French authorities to crack down on Istiqlal in 1944. The French swept up and arrested its leaders on trumped-up charges of helping the German war effort, provoking a wave of demonstrations in various cities which were violently suppressed.[174] In 1946, the new resident-general Eirik Labonne, reversed course, released political prisoners, and sought an accommodation with the nationalist parties.[175] In 1947, Muhammad V made a journey to Spanish-controlled Tangier, where he delivered a famous speech omitting any mention of the French, widely interpreted as expressing his desire for independence and aligning his objectives with that of Istiqlal.[176] This infuriated the pasha of Marrakesh, Thami El Gouali, who declared Muhammad V unfit to rule. Intriguing with the French general Augustin Guillaume, the new resident general since 1951, Thami El Glaoui engineered the deposition and exile of Muhammad V on 13 August 1953, replacing him with his uncle Mohammed ibn Arafa.[177] Nationalists fled into the Spanish zone, and a guerrilla war over the border into the French zone began soon after, encouraged by the Algerian War that had erupted next door. At length, El Glaoui changed his mind, and in October 1954, declared that Muhammad V ought to be reinstated.[178]

Despite vigorous opposition from the French colons in Morocco, the French government, facing deepening crises elsewhere overseas, finally agreed and signed the accords of La Celle-Saint-Cloud in November 1955. The restored Muhammad V returned to Morocco that same month, where he was received with near-hysterical joy. On March 2, 1956, France officially cancelled the 1912 treaty of Fez (Spain cancelled her own treaty a month later), and Morocco recovered her independence.[179] Thami El Glaoui, long-time pillar and symbol of the French colonial order, had died only a few months earlier, bringing an end to his despotic rule over Marrakesh.

Modern times

Following the death of El Glaoui in 1956, his vast family properties in and around Marrakesh were seized by the Moroccan state.[180] The urban development of Marrakesh continued primarily to the west. The modern downtown has been built primarily along Avenue Muhammad V connecting the Medina with Gueliz, with the town hall, banks, and major commercial buildings concentrated there, while Hivernage has sprouted ever more hotels and apartment complexes, displacing the exclusive luxury villas to the Palmerie east of the city. The Dar al-Makhzen (Palais Royal) in the Kasbah, profoundly overhauled by King Hassan II of Morocco, continues to serve as a secondary royal residence.[181] The Mellah, heavily depleted of its Jewish population since the mass emigration of Moroccan Jews to Israel after 1948 or to booming districts elsewhere (esp. Casablanca), has become less distinct from the rest of the Medina.[182]

Since independence, it has become commonplace to hear that while Rabat may be the political capital, Casablanca the economic capital, Fez the intellectual or traditional capital, Marrakesh remains the cultural and tourist capital of Morocco.[183]

Marrakesh certainly continued to thrive as a tourist destination, initially as a luxury wintering spot for wealthy Westerners, but soon drawing a wider clientele. The city became a trendy location to visit for hippies in the 1960s, a "hippie mecca", attracting numerous western rock stars and musicians, artists, film directors and actors, models, and fashion divas.[184] Tourism revenues doubled in Morocco between 1965 and 1970. Yves Saint Laurent, The Beatles, The Stones and Jean-Paul Getty all spent significant time in the city; Laurent bought a property here and renovated the Majorelle Gardens.[185][160] Due to the large number of American drifters arriving in Morocco and visiting Marrakech in the early 1970s, Moroccans were growing increasingly discontent that their country was being used as a "sort of countercultural waterhole". A 1973 article in The Nation reported that a crackdown by the Moroccan authorities had begun on westerners with long hair. By the mid-1970s, the dope colony which had formed in Morocco had been cleared out.[186] Expatriates with stylistic aspirations, especially from France, have poured investment into the city since this period, and developed many of the riads and palaces.[185] Old buildings were renovated in the Old Medina, new residences and commuter villages were built in the suburbs, and new hotels began to spring up.

United Nations agencies became active in Marrakech from the 1970s and its political presence internationally has grown with it. In 1982, UNESCO declared the old town area of Marrakech a UNESCO World Heritage Site, raising international awareness of the cultural heritage of the city.[187] In the 1980s, Patrick Guerand-Hermes purchased the 30-acre Ain el Quassimou, built by the Tolstoy family; which is now part of Polo Club de la Palmarie.[160] On April 15, 1994, the Marrakech Agreement was signed here which established the World Trade Organization,[188] and in March 1997, the World Water Council organized its First World Water Forum in Marrakech, attended by some 500 people internationally.[189] In the 21st century property and real estate development in the city has boomed, with a dramatic increase of new hotels and shopping centres, fuelled by the policies of the Moroccan King Mohammed VI of Morocco who has the goal of increasing the number of tourists visiting Morocco to 20 million a year by 2020.

In 2010 a major gas explosion occurred in the city.[190] On April 28, 2011, a bomb attack took place in the Djemaa el-Fna square of the old city, killing 15 people, mainly foreigners. The blast destroyed the nearby Argana Cafe.[190]

From November 7 to 18, 2016, the city of Marrakesh was host to the meeting of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known as the 22nd Session of the Conference of the Parties, or COP 22. Also known as 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference it also served as the first meeting of the governing body of the Paris Agreement, known by the acronym CMA1. The UNFCCC secretariat (UN Climate Change) was established in 1992 when countries adopted the UNFCCC. In recent years, the secretariat also supports the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, agreed by governments to signal that successful climate action requires strong support from a wide range of actors, including regions, cities, business, investors and all parts of civil society.[191] Commencing six months ahead of the start of the UN Climate Change Conference in Marrakesh, construction work at the Bab Ighli site was launched. The site was composed of two zones. The “Blue Zone”, placed under the authority of the United Nations, and spanning 154,000 m2 and consisting notably of two plenary rooms, 30 conference and meeting rooms for negotiators and 10 meeting rooms reserved for observers. The second zone, the "Green Zone", was reserved for non-state actors, NGOs, private companies, state institutions and organizations, and local authorities within two areas (“civil society” and “innovations”) each measuring 12,000 m2. The area will also include spaces dedicated to exhibitions and restaurants. The total surface of the Bab Ighli site will be 223,647 m2 (more than 80,000 m2 covered by a roof).[192]

Notes

- Searight 1999, p. 378.

- Messier (2010: p.35); Levi-Provençal (1913-38)

- Ibn Idhari, Bayan al-Mughrib, quoted in Levtzion and Hopkins (1981:p.226-27); Messier (2010: p.41)

- van Hulle (1994: p.10)

- Ibn Abi Zar (writing 1315) has Marrakesh founded c. 1061, just before the Almoravid campaign against Maghrawa-held Fez, which he dates 1063. Ibn Idhari (writing 1313) has Marrakesh founded in 1070, and dates the campaign against Fez in 1072-73. Ibn Abi Zar's chronology was followed by Ibn Khaldoun (wr. 1374-78), and thus given the popularity of Ibn Khaldoun, the c. 1061 date is often cited in Western texts. But al-Bakri (wr. 1067-67) does not mention Marrakesh, and the anonymous writer of the al-Hulal al-mawshiyya (wr.1381) follows Ibn Idhari's 1070 date. For more details on the dating problem, see Messier (2010: p.201)

- Ibn Idhari, as quoted in Levtzion and Hopkins (1981: p.226-27). Messier (2010: pp. xii, 41-42; 53)

- Messier (2010: p.53-56), Lamzah (2008: p.57). Some modern texts erroneously suggest Yusuf ibn Tasfhin founded Marrakesh; this is usually a result of mistaken local legend and a careless misstatement in Ibn Khaldun's account.

- Meakin (1901: p.289); Lamzah (2008: p.36)

- Messier (2010, pp.42, 59, 85); Julien (1931 (1961 ed): p.82)

- Viollet, Pierre-Louis (2017-10-02). Water Engineering inAncient Civilizations: 5,000 Years of History. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-37531-0. Archived from the original on 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Messier (2010: p.41-42)

- Messier (2010: p.85, 87)

- Messier (2010, p.122-23)

- Messier (2010, p.123-24)

- Messier (2010: p.126)

- Cenival (1913-36: p.297; 2007: p.321)

- Messier (2010: p.125-26)

- Messier (2010: p.126), Wilbaux et al. (1999)

- Messier (2010: p.87).

- Messier (2010: p.126); the closest city with Jewish quarter was eight miles to the southeast in 'Aghmat Aylana', twin of Aghmat proper ('Aghmat Ourika') (Gottreich, 1987: p.13)

- Cenival (1913-36: p.298; 2007: p.322)

- For descriptions of El Hara, see Meakin (1901: p.291-92); Bensusan (1904: 94-95)

- Wilbaux (1999: p.108); Rogerson (2000:p.115). Interestingly, Gottereich (2007: p.115-6) suggests Yusuf ibn Ali may have been a Jew, or certainly adopted by Marrakeshi Jews as a saint of their own.

- Bosworth (1989: p.592); Park and Boum (1996: p.238)

- كتاب الحلل الموشية في ذكر الأخبار المراكشية (in Arabic). مطبعة التقدم،. 1811. p. 71.

- Deverdun, Gaston (1959). Marrakech: Des origines à 1912. Rabat: Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines. pp. 108–109.

- Messier (2010: p.143-44). Lamzah (2008: p.56-57) dates their completion to 1126.

- Cenival (1913-36: p.296; 2007: p.324)

- Messier (2010: p.168)

- Allain, Charles; Deverdun, Gaston (1957). "Les portes anciennes de Marrakech". Hespéris. 44: 85–126. Archived from the original on 2020-01-14. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- Bennison, Amira K. (2016). The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press.

- Salmon, Xavier (2018). Maroc Almoravide et Almohade: Architecture et décors au temps des conquérants, 1055-1269. Paris: LienArt.

- Only the trace of the original Koutoubia remains, but the original look can be deduced from the contemporary still-standing mosques of Tinmel and Taza, which were very similar (Julien, 1931: p.126-27)). For a description of Tinmel, see Ewert (1992).

- Julien (1931: p.126); Lamzah (2008:p.58)

- Julien (1931: p.127)

- Montalbano (2008: p.711).

- Julien (1931: p.126-29); Casamar Pérez (1992); Ewert (1992)

- Barrows 2004, p. 85.

- Cenival (1913-36: p.298; 2007: p.321), Lamzah (2008: p.59)

- e.g. 1246 letter from Pope Innocent IV.

- e.g. Meakin (1901: p.199)

- Cenival (1913-38: p.300; 2007: p.324)

- Julien (1931: p.163-64)

- Julien (1931:p.167-68); Cenival (1913-36: p.301; 2007: p.325)

- Julien (1931:p.170)

- Bloom and Blair (2009: p.466); Ghachem-Benkirane and Saharoff (1990: p.34); Levtzion (1977: p.360); Julien (1931: pp.187-90, 193)

- Julien (1931: p.188); Cornell (1997: p.128)

- Bloom and Blair (2009: p.466). Some sources suggest Ben Saleh mosque it was built earlier, by Abu Sa'id Uthman II, between 1318 and 1321. Cenival (1913-36 p.301, 303) identifies it as the zawiya of the saint "Muhammad ibn Salih". Identification uncertain, possibly related to Abu Muhammad Salih of the Magiriyya strand of Sufism, based in Safi, who were favored by the Marinids. (See Cornell, 1997: p.140)

- Although it is sometimes said the Abu al-Hasan Madrasa was later refurbished by the Saadians into the Ben Youssef Madrasa, it has since been determined they were quite distinct and separate institutions; the outline of the ruins of the Abu al-Hasan Madrasa are just north of Kasbah mosque, while the Ben Yussef Madrasa is by the namesake mosque. See Cenival (1913-36: p.305); Bloom & Blair (2009:p.466).

- Julien (1931: p.172); Cenival (1913-38: p.301; 2007: p.325)

- Cenival (1913-36: p.301; 2007: p.325-6)

- Julien (p.174)

- Julien (1931: p.177)

- Julien (1931: p.181)

- Julien (1931: p.183-84); Cornell (1998: p.163)

- Julien (1931: p.184)

- Julien (1931: p.185)

- Julien (1931: p.185); Park and Boum (1996: p.239)

- Contrary to what is occasionally claimed (e.g. Park and Boum, 1996: p.239), Marrakesh's participation is listed in Portuguese chronicles e.g. Ruy de Pina (Chronica de D. Duarte), reports that the Marinid host at Tangier in 1437 included the rulers of Fez, Velez, Tafilelt and "El Rei de Marrocos". (c. 1500 p.111 Archived 2017-03-29 at the Wayback Machine).

- Julien (1931: p.199); Park and Boum (1996: p.239)

- Levtzion (1977:p.400), Julien (1931: p.197-98). See Cornell (1997: 123ff) for more details Sufism under the Marinids.

- Julien (1931: p.198). For more on al-Jazuli, see Cornell (1997: ch. 6, esp. pp.167ff.)