History of Nahuatl

The history of the Nahuatl, Aztec or Mexicano language can be traced back to the time when Teotihuacan flourished. From the 4th century AD to the present, the journey and development of the language and its dialect varieties have gone through a large number of periods and processes, the language being used by various peoples, civilizations and states throughout the history of the cultural area of Mesoamerica.

Like the history of languages, it is analyzed from two main different points of view: the internal one —the processes of change in the language— and the external one —the changes in the sociopolitical context where the language is spoken—. From this, based on the proposal for the classification of the evolution of attested Nahuatl by Ángel María Garibay,[2] the history of the language is divided into the following stages:

- Archaic era (until 1430).

- Classical period (1430–1521).

- Contact era (1521–1600).

- Reflosure era (1600–1767).

- Decline period (1767–1857).

- Modern era (1857–present).

Based on linguistic and historical studies, Andrés Hasler points out that it is in the archaic era when the two main forms of the language emerged that gave rise to today's linguistic variants: Paleonahua and Neonahua.[3] The Paleonahua developed over several centuries, beginning its process of change during the Teotihuacan era, being more conservative in eastern Mesoamerica. Neonahua, however, arose when the Toltec-Chichimecs spread throughout much of the Valley of Mexico, with linguistic innovations such as the addition of the sound /tɬ/.[4]

Introduction

Origins

On the question of geographic point of origin, 20th-century linguists agreed that the Yutonahua language family originated in the Southwestern United States.[5][6] The Uto-Aztecan family has been accepted by linguists as a linguistic family since the beginning of the same century, and six subgroups are generally accepted as valid: Numic, Takic, Pimic, Taracahita, Corachol, and Aztecan.

Both archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence supports a southward spread across the Americas; this movement of speaking communities took place in several waves from the deserts of northern present-day Mexico to central Mexico. Proto-Nahua, therefore, arose in the region between Chihuahua and Durango where, occupying a greater extension of territory, it quickly formed two variants, one that continued to spread south with innovative changes (Neonahua) while the other (Paleonahua), with conservative features of the Yutonahua, moved to the east.

The proposed migration of speakers of the Proto-Nahuan language in the Mesoamerican region has been placed at some point around the year 500, towards the end of the Early Classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.[7] Before reaching central Mexico, pre-Nahua groups probably spent a period of time in contact with the Cora and Huichol languages of western Mexico (which are also Uto-Aztec).[7]

Nahuan languages

The Nahuan or Aztecan languages are a branch of Yutonahua family that have been the object of a phonetic change, known as Whorf's law, which changed an original *t to /tɬ/ before *a,[8] in Mexico "Nahuatlano" has been proposed to designate to this family. Later, some Nahuan languages have changed this /tɬ/ to /l/ or back to /t/, but it can still be seen that the language went through a /tɬ/ stage.[9]

In Nahuatl, the absolutive state in the singular is marked with /-tli/ and the possessed state with /-wi/ (both suffixes derived from Proto-Uto-Aztecan /*-ta/ and /*-wa/). Regarding plural marks, the suffixes /-meh/ (from the Proto-Uto-Aztecan /*-mi/) and sometimes /-tin/, /-tinih/ and /-h/ are used above all, and to a lesser degree reduplication of the initial syllable is used, although this in Nahuatl, unlike Uto-Aztecan languages such as Huarijio or Pima, is marginal.

Dakin argues that the key correspondence sets used by Campbell and Langacker as evidence for the existence of a separate fifth vowel *ï evolving from Proto-Uto-Aztecan *u, their main basis for separating the Pochutec language from "general Aztec", were in actually later developments by which Proto-Nahuan *i and *e > o in closed syllables, and that the supposed contrast in final position in imperatives had originally had a following clitic.

Archaic era

Teotihuacan

The emergence —and spread— of Nahuatl and its variants in the Basin of Mexico took place during the heyday of Teotihuacan (c. 100–650 AD). The Teotihuacan trade routes served for a rapid spread of the new language. The ethnolinguistic identity of the founders and inhabitants of Teotihuacan is unknown; however, it has long been the subject of debate; thus, in the 19th and 20th centuries, some researchers believed that Teotihuacán had been founded by Nahuata speakers; later, towards the end of the last century, linguistic and archaeological research began to contradict that point of view.

Kaufman accepts, like several modern authors,[10] the probability that a Nahua variant was spoken in the city, but from his point of view, the Coyotlatelco culture,[11] which is associated with the Teotihuacan sunset, is the first whose bearers must undoubtedly have been speakers of Nahuatl in Mesoamerica, as it was particularly spread by it.[12] Likewise, the hypothesis of Nahuatl in the city has gained strength in recent decades, and its arguments begin to be resonant for modern research after the conclusions of Gómez and King: according to new grotochronological perspectives, they suggest the existence of a Proto-Nahuan Pochutec in the city, which must have been the ancestor of all modern Nahua variants.[13]

Considering that Teotihuacan exerted a great influence in a large part of Mesoamerica, the fact that loanwords from Nahuatl exist in Mayan glyphs of the 4th and 5th centuries indicates that there was surely a link or connection between Nahuatl and the Teotihuacans.[14]

It is also believed that it is more likely that the Teotihuacan language was related to Totonac or was of Mixe-Zoquean origin.[15] Much of the Nahua migration to central Mexico was a consequence and not a cause of the fall of Teotihuacan.[16] From these early times, loans were given between the different linguistic families, even at the morphosyntactic level. After the Nahuas arrived in the high culture zone of Mesoamerica, their language also adopted some of the features that define the Mesoamerican linguistic area;[17] thus, for example, the Nahuas adopted the use of relational nouns and a form of possessive construction typical of Mesoamerican languages.[18]

After the collapse of the big city, new models emerged to hold power. Along with these models, it is believed that the Nahuatl language developed.[19] By then, it was not only spoken by its natives, since little by little it was being adopted by older Otomanguean groups that had depended on Teotihuacan. When Tula Chico was founded in the 7th century, the Nahua influence was already evident, although it was not very intense.

Paleonahua characteristics

The features that stand out and that can still be found today in variants derived from Paleonahua are:[4]

- Preservation of [t] sound. Example:

- paleonahua siwat [ˈsiwaːt] ('woman') → neonahua sowatl [ˈsowat͡ɬ] (cf. Pipil siwat [ˈsiwat]).

- Use of the closed vowel [u]. Example:

- paleonahua ukwilin [uˈkʷilin̥] ('worm') → neonahua okwilin [oˈkʷilin̥] (cf. Pochutec ugꞌlóm [ugˀˈlom]).

- Preservation of [a]. Example:

- paleonahua ahakat [ahˈakat] ('wind') → neonahua yehyekatl [jeʔˈjekat͡ɬ] (cf. Pipil ejekat [ehˈekat]).

- Use of three absolutives: -t, -ti and -in. Examples:

- paleonahua nalwat ('root') → neonahua nelwatl.

- paleonahua tixti ('mass') → neonahua textli.

- paleonahua ahsilin ('nit') → neonahua ahselin.

- Use of plural -mih. Example:

- paleonahua masat ('deer') > masamih ('deers') → neonahua masatl > mamasah.

- The plural suffix does not replace the absolutive -in. Example:

- paleonahua tuchin ('rabbit') > tuchinmih ('rabbits') → neonahua tochin > totochtin.

- Use of the preterite suffix -ki in the second conjugation. Example:

- paleonahua kikuhki ('he bought it') → neonahua okikow.

- Use of the -ket agent suffix. Example:

- paleonahua yahket ('pilgrim') → neonahua yawki.

- paleonahua teemachtihket ('teacher') → neonahua teemachtihki.

Neonahua period

Three hundred years later, when the Toltec-Chichimecs (recognized by sources as "Nahua-Chichimecs") arrived in the center of present-day Mexico, the city of "Tollan" (today Tula) was founded again, sharing power with the Nonohualcas. In this way, the Toltec-Chichimecs they were the only Neonahuas to reach the Huasteca region,[4] cornering the Paleonahua and developing a mixture of Paleonahua and Neonahua, which is why the communities of "T variant" speakers are surrounded by those of "TL variant".[20]

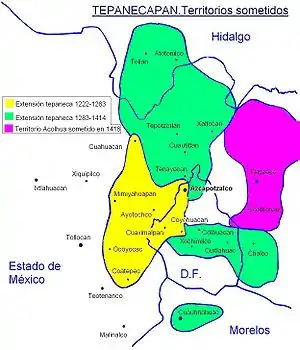

It is at this time that Nahuatl acquires political relevance. In the Central Altiplano, on the other hand, there was a large number of Neonahua peoples in expansion, such as the Teochichimecs (later known as Tlaxcaltecs, who expelled the Olmeca-Xicalancas), the Xochimilcas, the Tepanecs (with their capital in Azcapotzalco, who originally spoke a variant of Otomi)[21] and the Acolhuas of Texcoco (who adopted it in the 14th century),[22] among others. Archaeological investigations have revealed that Azcapotzalco was inhabited since the classical period (around the year 600) and related to Teotihuacans in culture and language, as it is known that they still spoke an Otomi language in the fourteenth century despite the fact that Nahuatl was already the lingua franca from 1272.

The last Neonahuas to arrive in the region were the Aztecs.[4] By then, the Tepanecs controlled the region through a triple alliance government since 1047 (according to Chimalpahin) between Azcapotzalco, Colhuacan and Coatlichan, the latter being replaced in 1370 by Texcoco (according to Alva Ixtlilxochitl).[23] At this time, the sacred poems of the Manuscripts of Cuauhtitlan and Coatlichan were written.[2] Likewise, the Twenty Poems collected by Sahagún and the poems found in the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca date from the archaic era.

In the Tepanec War, the Tenochcas, supported by the Acolhuas, Huexotzinco and Tlaxcala, conquered Azcapotzalco in 1428. They also subdued Tlacopan and other Tepanecs, finally defeating them in Coyoacan in 1430. The Tenochcas, having gained their independence, established the Triple Alliance between Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan, beginning the classical period of the language.

Neonahua characteristics

The features that stand out and that can still be found today in variants derived from Neonahua are:[4]

- Development of the sound [t͡ɬ] (due to Totonac influence). Example:

- paleonahua uhti [ˈuhtɪˀ] ('road') → neonahua ohtli [ˈoʔt͡ɬɪˀ] (cf. Pipil ujti [ˈuhti]).

- Use of the semi-closed vowel [o]. Example:

- paleonahua ulut [ˈuːluːt] ('cob') → neonahua olotl [ˈoːloːt͡ɬ] (cf. Pipil ulut [ˈulut]).

- Development of initial y- before [e]. Example:

- paleonahua epat [ˈepat] ('skunk') → neonahua yepatl [ˈjepat͡ɬ].

- Use of four absolutives: -tl, -tli, -li and -in. Examples:

- paleonahua atimit ('louse') → neonahua atemitl.

- paleonahua nekti ('honey') → neonahua nekwtli.

- paleonahua takwal ('food') → neonahua tlakwalli.

- paleonahua tuchin ('rabbit') → neonahua tochin.

- Use of the plurals -meh and -tin; loss of the absolutive -in in the plural. Examples:

- paleonahua masat ('deer') > masamih ('deers') → neonahua masatl > masameh.

- paleonahua tuchin ('rabbit') > tuchinmih ('rabbits') → neonahua tochin > tochtin.

- Development of the prefix o- in the preterite and loss of -ki. Example:

- paleonahua kipuhki ('he counted it') → neonahua okipow.

- Tendency to merge vowels in different syllables. Examples:

- paleonahua nuuhwi ('my path') → neonahua nohwi.

- paleonahua nuiknih ('my sibling') → neonahua nokniw.

Classical period

Garibay refers to this stage as the "golden age" of the Aztec language. It is at this time that Nahuatl literature is perfected, with works such as the Cantares Mexicanos and the Romances de los señores de Nueva España.[2] Some important characteristics of the classical era are: a great abundance of lexicon, a great clarity in the language, an improvement in syntax and, finally, elegance through stylistic procedures such as diphrasing and phrase parallelism.

The political and linguistic influence of the Aztecs came to extend into the Mesoamerican area and Nahuatl became a lingua franca among merchants and elites in the region, for example among the Kʼicheʼ. Tenochtitlan grew to become the largest Mesoamerican urban center, attracting Nahuatl speakers from other areas in which it had spread in previous centuries, giving rise to an urban form of Nahuatl with diverse characteristics, which came to be known as Classical Nahuatl.[24] Following this idea, it is believed that the language of the capital was a koiné resulting from contact between speakers of different variants.[25]

Nahuatl was becoming more and more refined due to the complex life of the times. In this way the tekpillahtolli[26] or "speech of the pipiltin (nobles)" was born,[27] the cultured and elegant Classic Nahuatl.[28] Due to its name, it has been popularly believed that it is the mother tongue of all the variants of the language, which is a mistake; not all variants descend from Classical Nahuatl, nor are all ancient documents written in this variant. In fact, in the same capital of the Aztec Empire there was variation in the speech of the nobles (pipiltin) and the common people (masewaltin). The second is known as masewallahtolli "common speech".[29]

Throughout the 15th century this trend grew, mainly due to prominent authors such as Tecayehuatzin of Huexotzinco, Temilotzin of Tlatelolco, Macuilxochitzin, Tlaltecatzin of Cuauhchinanco, Cuacuauhtzin of Tepechpan, Nezahualcoyotl and Nezahualpilli of Texcoco.[30]

Nezahualcoyotl, after the Tepanec War, began his government in Texcoco. Likewise, he gained a reputation as a sage and gained just fame as a poet. His extensive intellectual training translated into a high aesthetic sensitivity and a great love for nature, which were reflected not only in the architecture of the city, but also in his poetic and philosophical manifestations. Nezahualcoyotl even built a botanical garden adorned with beautiful pools of water and aqueducts in Tetzcotzingo, where meetings of poets were common.

Apart from learning at home, there were compulsory education institutions where they learned to distinguish common speech (masewallahtolli) from elegant speech (tekpillahtolli). In the indigenous schools (telpochkalli, kalmekak and kwikakalli)[31] much emphasis was placed on the acquisition of public speaking skills, long moral and historical speeches, plays and songs were learned by heart. This made language teaching and education itself a model of success.[32]

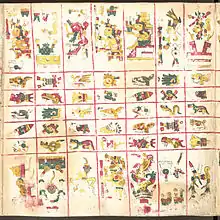

The tlacuilos,[33] macehuales[34] and pochtecas used the Aztec script to write and use the topographical codices.[35] Aztec literature was recorded in amoxtli on deerskin, maguey paper, palm paper, or amate paper. Amate paper was used extensively for religious and commercial purposes (writing surface, ritual items, economic transaction documents, inventory records, etc.). Among the best-known Nahua documents made with amate paper are the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer and the Codex Borgia.

The existence of logograms (Aztec script) has been documented since the conquest. Recently, the phonetic aspect of its writing system has been discovered,[36] although many of the syllabic characters had already been documented since the 16th century by Bartolomé de las Casas[37] and analyzed centuries later by Zelia Nuttall and Aubin.[38]

Contact era

1521–1556

With the arrival of the Spaniards in the heart of Mexico in 1519 and, mainly, from 1521, when the Spanish and Tlaxcalan conquest of the Aztec Empire was completed, the situation of the Nahuatl language would change significantly; on the one hand, a slight displacement by the Spanish language begins; on the other, its official use for communication with the natives generated the establishment of new settlements; At the same time, extensive documentation was created in Latin script, establishing a reliable record for its preservation and understanding, so the language continued to be important in the Nahua communities in the Spanish Empire.

To transmit the preaching of the gospel and instruct the indigenous people in the Catholic faith, the Franciscans with Pedro de Gante (a Belgian missionary, a relative of Emperor Charles V)[39] began to learn in the year 1523, thanks to the Nahua elites, educated variants of the Aztec language, mainly those spoken in the cities of Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco and Tlaxcala.[40] At the same time, the missionaries undertook the writing of grammars of the indigenous languages for use by priests.

For evangelization in New Spain, Testerian catechisms are documents of historical relevance since they explain the precepts of Catholic doctrine through images based on indigenous conventions prior to the Conquest and sometimes incorporate Western writing in Spanish and other languages.[41][42][43] These owe their name to Jacobo de Testera (or Jacobo de Tastera), a French missionary who compiled catechisms of this type from the indigenous authors of his.

The first Nahuatl grammar written in 1531 by the Franciscans is lost, the oldest preserved, the Arte de la lengua mexicana, was written by Andrés de Olmos in the Hueytlalpan convent and published in 1547. The Art of Olmos was the first properly developed grammar and oldest known. It was then up to Nahuatl to be the first language in the New World to have an art or grammar.[44] Also noteworthy is the fact that it was developed before many grammars of European languages, such as that of the French language, and only 55 years after Antonio de Nebrija's Gramática de la lengua castellana.

In 1535, the year in which the Viceroyalty of New Spain was established, a series of attitudes and policies began regarding Amerindian languages, which began to have relevance in matters of the Hispanic Monarchy and the Catholic Church. It is in that same year that King Charles I of Spain orders that schools be established to teach "Christianity, good customs, police and the Spanish language" to the children of the indigenous nobility.[45] Then the Franciscan missionaries founded schools —such as the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1536— for the indigenous nobility with the purpose of re-educating them within the Western canons, where they learned theology, grammar, music, mathematics.

Annals of Tlatelolco is the title of a codex in Nahuatl written around the year 1540 by anonymous Nahua authors.[46][47] This document is the only one that contains the day the Aztecs left Aztlan-Colhuacan, as well as the day of the founding of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.[48] Unlike the Florentine Codex and its account of the conquest of Mexico, the Annals of Tlatelolco remained in indigenous hands, providing an authentic insight into the thoughts and perspectives of the newly conquered Nahuas.

Through the Conquest of Guatemala, carried out by Spaniards and allies of various groups originating from central Mexico, mainly Tlaxcaltecs and Cholultecs, Nahuatl spread before and further than Spanish. In this way, it became the language of conquest in the colonial era. Likewise, the language advanced along with the conquering armies through Central America,[49][50] which led to the place names of a large part of the Mesoamerican area being Nahuatized, becoming official Christian names, still in force today along with the traditional Mayan names.[28]

On 7 June 1550, in the name of Emperor Charles, the teaching of Spanish was ordered to the indigenous people of all the provinces in America through the missionaries.[45] That same year, Fray Rodrigo de la Cruz, suggested to the king that he change the order of teaching the Spanish language for that of the Aztec language, affirming that many indigenous people confess in it and considering it a "very elegant language".[51]

The Spanish realized the importance of the language and preferred to continue its use than to change it, they also found that learning all the indigenous languages was impossible in practice, so they concentrated on Nahuatl. In fact, despite the efforts of the crown, the Franciscans continued to teach Nahuatl in Neo-Galician convents.[45] In 1552, the Franciscans requested permission to teach Nahuatl in the Mayab because the Maya did not want to learn Spanish.[49]

The first vocabulary of the language, entitled Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana, was written by Alonso de Molina and published in 1555. By this time the writing of Nahuatl in the Latin alphabet was common. Throughout the century, Mexicano remained the most widely used language, imposing itself on others through indigenous evangelists and catechists, forcing speakers of other Mesoamerican languages to become literate first in Nahuatl and later in their mother tongue.[40]

1556–1600

When Philip II of Spain came to the Spanish throne in 1556, the position of the crown on the linguistic matters of the Spanish Empire changed drastically. In the year 1558, Viceroy Luís de Velasco wrote to King Philip II to support the initiative of the Franciscans to teach Nahuatl in Nueva Galicia as a general language.[45] This is mainly due to the fact that both the crown and the ecclesiastical entities were interested in the linguistic wealth of the empire, seeing it as a form of political, economic and religious expansion rather than an obstacle.[52][53]

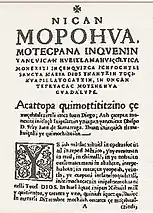

The Nahua nobleman and scholar Antonio Valeriano, ruler of Tenochtitlan and Azcapotzalco, is credited with authorship of one of the most outstanding and important works of Nahuatl literature, the Nican Mopohua,[54] which dates back to 1556.[55] Valeriano studied and was later a teacher and rector at the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. Sahagún refers to him as "the principal and wisest" of his students.[56] With Sahagún, he participated in the creation of the Florentine Codex and also taught the Nahuatl language to Juan de Torquemada, author of the Monarquía indiana. In addition, he was one of the most notable disciples and informant of Bernardino de Sahagún and Andrés de Olmos.

In 1569, a description written by Neo-Galician Franciscans explains the promotion of Nahuatl carried out by friars in Nueva Galicia to teach Christian doctrine. The religious reported the teaching of the Aztec language and the doctrine in both Mexicano and Latin in the report prepared at the request of Juan de Ovando, the king's visitor.[51]

That is when, in the year 1570, King Philip II decreed that Nahuatl should become the official language in New Spain to facilitate communication between the Spanish and the natives of the viceroyalty.[57] In the decree, the monarch orders that "the said Indians should all learn the same language and that this be Mexicano, which could be learned more easily because it is a general language."[58]

This was followed by the fact that, in 1578, the king ordered that no religious who did not speak Mexicano would have the authorization to take charge of missions or parishes.[59] Two years later, he issued the certificate that created the chairs of languages in the universities of America. Novohispanic music in Nahuatl also appears in this century, giving rise to compositions such as the motets In ilhuicac cihuapillé and Dios itlaçònantziné attributable to Hernando Franco and taken from the Codex Valdés.[60] Another outstanding colonial song in Nahuatl is Teponazcuicatl.[61]

At that time, in the Kingdom of Guatemala, colonial Central American Nahuatl was formed, which, by ultracorrection, used "tl" where in Classical Nahuatl there was "t" and replaced the classical "tla" with "ta". For example, tetahtzin became tetlahtzin, titechnamiqui became tlitechnamiqui, and tlalli became talli. Also, there was a tendency to turn the "u" into "o". The Memorias en lengua náhuatl enviadas a Felipe II por indígenas del valle de Guatemala hacia 1572 are the most extensive attested examples of Central American Nahuatl.[49]

The Jesuits were the religious order that most promoted syncretism and indianization. In 1579, Father Pedro Morales wrote the Carta annua, in which he describes and explains in detail the festivities held by the Jesuits when Pope Gregory XIII donated relics to New Spain. In the letter he includes several poems in Mexicano, Spanish, Italian and Latin. These are some of the verses:

Tocniane touian

ti quin to namiquiliti

in Dios vel ytlaçouan

matiquinto tlapaluiti.

In the year 1580, Juan Suárez de Peralta, nephew of Hernán Cortés, wrote from Spain about the knowledge of Nahuatl by the criollos. In that text he explains that "there are great secrets among the Indians, none of which they will reveal to the Spanish if he breaks them into pieces; to those of us who were born in New Spain who consider us to be children of the land and natural and communicate many things to us, and more so as we know the language, it is great conformity for them and friendship."[62] Two years later, an edict was published in Guadalajara, Valladolid and Mexico with the announcement of an opposition contest for the chair in Nahuatl. There were later complaints in the Audiencia de Nueva Galicia because the bishop had appointed priests who had not taken the test of proficiency in the Aztec language.[58]

In 1585, Bernardino de Sahagún finished writing his work entitled General History of the Things of New Spain, which he had begun to write since 1540.[63] It is commonly known by the name of the Florentine Codex. This encyclopedic work, made up of 12 volumes in Nahuatl and some parts in Spanish and Latin, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[64]

That same year, the III Mexican Council ordered that the parish priests use the native language of their respective regions, but prohibited the ordination of indigenous people as priests, the latter thought not to promote advanced studies among indigenous people, although, in fact, indigenous They attended the University of Mexico to study various careers, since only Spaniards and indigenous people of the nobility could access education.[65]

In July 1591, 71 Tlaxcalan families and 16 singles arrived in Saltillo and the town of San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala was founded on the western side of the Spanish settlement and separated from the Spanish only by an irrigation canal.[66] In this way, Nahuatl arrived in the north of what is now Mexico, specifically in the current states of Coahuila and Nuevo León, through the Tlaxcalan colonization.[67]

In 1596, the Council of the Indies proposed that the use of Spanish be made compulsory for the indigenous nobility, arguing that the use of indigenous languages would give advantages to Creole and mestizo priests over peninsular priests. However, the king rejected the proposal, arguing that the best thing was to only have teachers "for those who voluntarily wanted to learn the Castilian language." On the other hand, the king instructed the viceroy that schools for indigenous girls should not use their languages.[58]

Gerónimo de Mendieta, a Basque and Nahuatl Franciscan, finished writing in 1597 the work that has made him famous, the Historia ecclesiástica indiana, which is a chronicle of evangelization in New Spain. In it, he refers to Nahuatl as a general language that generated a broad bilingualism and explains that the "Mexicano is the general language that runs through all the provinces of this New Spain." In addition, he describes that "everywhere there are interpreters who understand and speak Mexicano because this is the one that runs everywhere, like Latin through all the kingdoms of Europe." Mendieta, in the same text, also left his opinion on the language, stating that "Mexicano is no less gallant and curious than the Latin, and I even think that more artful in composition and derivation of words, and in metaphors."[62]

Around 1598, Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, grandson of the tlahtoani Moctezuma II,[68] wrote the Crónica Mexicayotl, with some insertions by Alonso Franco and Domingo Francisco Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin.[69] The work, written in Nahuatl, narrates the history of the Aztec people from their departure from Aztlán until the beginning of the Conquest of Mexico. Additionally, he was well known and famous among natives and Spaniards; and because of his noble position, he was able to have training in the culture of the conquistadors.[70][71] It is also often affirmed, with greater certainty, that he served as a Nahuatlato (expert interpreter of Nahuatl) in the Real Audiencia of Mexico in that same year.[72]

Reflosure era

1600–1686

It is at this time that the Aztec language reached the status of a prestigious language, coexisting with Latin and Spanish.[73] Peninsulares, criollos, mestizos and indigenous people wrote in the language during this time, through the integration of it in their written works. In addition, most of the inhabitants of New Spain used it orally regardless of whether they were of Amerindian, European or African origin.[62]

During this period the Spanish Crown allows a high degree of autonomy in the local administration of the indigenous peoples, and in many towns the Nahuatl language was the de facto official language, both written and spoken.[57][74] Classical Nahuatl was used as a literary language, and a large corpus of documents from that period survives to the present day. Works from this period include histories, chronicles, poetry, plays, Christian canonical works, ethnographic descriptions, and administrative documents.[75]

In the year 1603, King Philip III of Spain, having received reports that the friars were not sufficiently prepared in the linguistic field, ordered that the clerics must know the indigenous language of those they indoctrinated. In addition, he authorized the examination of religious and allowed them to be removed from the parishes if they did not have the required sufficiency.[58]

Gaspar Fernandes, a composer and organist from New Spain, specifically Guatemalan,[76] active as chapel master in the cathedrals of Guatemala and Puebla, was the author of the Musical Songbook, an important document preserved in the Musical Archive of the Oaxaca Cathedral, which contains more than 300 popular religious chants, composed between the years 1609 and 1616, in Spanish, Nahuatl and Portuguese.[77][78] Among the most outstanding and well-known is the Christmas carol Xicochi conetzintlé.

A few years later, in 1619, a royal decree increased the pressure on the friars in the linguistic matter, ordering that "the viceroys ensure that the clerics and religious who do not know the language of the Indians and were doctriners are removed and put others who know it." Two years later, Philip IV of Spain came to the throne, establishing that same year that the linguistic knowledge of the friars should be examined every time they moved from parish.[58]

In 1623, Juan de Grijalva, an Augustinian chronicler, explains that, faced with a large number of languages throughout the viceroyalty, it was concluded that using the most widely spoken language of each province would be the best option for missionary work. Likewise, although the establishment of chairs in languages had already been decreed in the second half of the 16th century, it was not until 1626 when the chairs of Nahuatl and Otomi were finally established at the University of Mexico.[59][79]

Between 1607 and 1631, Domingo Francisco Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, an indigenous historian, wrote a set of historical works written in Nahuatl known as the Relaciones de Chimalpahin, also under the name Different Original Stories.[80] The chronicler also wrote a work in Nahuatl called Diario de Chimalpahin,[81] in which he records the visit of Hasekura Tsunenaga and, in general, the first Japanese embassy to the Viceroyalty of New Spain.[82]

Around the year 1645 there is news of four more published works whose authors are, in 1571 Alonso de Molina, in 1595 Antonio del Rincón, in 1642 Diego de Galdo Guzmán and in 1645 Horacio Carochi. The latter, a Jesuit philologist originally from Florence, is considered today the most important of the grammarians of the viceregal era. It was in 1644 when he concluded the Arte de la lengua mexicana,[83] which was reviewed and praised by Father Balthazar González S.J his friend Bartholomé de Alva who had translated the comedies of Lope de Vega and the auto sacramental The great theater of the world by Calderón de la Barca into Nahuatl.[84]

Carochi has been especially important for researchers working in the new philology,[85] due to his scientific approach that precedes modern linguistic research, analyzes phonological aspects in more detail than his predecessors and even successors, who had not taken pronunciation into account of the glottal stop (saltillo), which is actually a consonant, or the vowel length.

Huei tlamahuiçoltica is the abbreviated name of the literary work in Nahuatl, published in 1649 by the criollo priest Luis Lasso de la Vega, where the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the indigenous Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin in 1531 are recounted. This work, in fact , contains works written by indigenous nobles, such as the Nican Mopohua by Antonio Valeriano and the Nican Motecpana by Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (a direct descendant of Nezahualcoyotl), a list of 14 miracles attributed to the Virgin.

Due to the difficulty of finding professors with bilingual knowledge of Mexicano and Otomi, in 1670, the chair was duplicated, creating one only for Nahuatl and another only for Otomi.[58] In 1673, Agustín de Vetancurt wrote an Arte de la lengua mexicana.

In the year 1676, Juana Inés de la Cruz, a Hieronymite nun and Novohispanic writer from Nepantla, wrote the set of Villancicos a la Asunción,[86] which incorporates a good number of stanzas in Nahuatl.[87] Juana Inés de la Cruz, also known as the tenth muse, contributed to Nahuatl literature the tocotines of her Christmas carols,[88] her best known being Tonantzin, although she also wrote other bilingual poems in Spanish and Mexicano.[89]

At this time, Christianized Nahuatl spread widely thanks to printing press and trade. Therefore, merchants traveling through the provinces had access to Nahuatl vocabularies, which were sold throughout New Spain.[28]

1686–1767

For a time, the linguistic situation in New Spain remained relatively stable,[62] but in 1686 King Charles II of Spain issued a royal decree that prohibited the use of any language other than Spanish throughout the Spanish Empire, reiterating it in 1691 and 1693, in which he dictated the creation of the "school plot" for the teaching of the imperial language.[90]

At this time there are testimonies indicating that the Spanish spoke in Mexicano directly with their troops, trading, in government and at home, giving rise to a situation of diglossia and bilingualism. In the case of the criollos and mestizos, learning Nahuatl was inevitable, since it began in childhood due to contact with the native population. The expansion of the language also continued, because in Santiago Guatemala Nahuatl classes were given on Saturdays, attended by students who spoke Mayan languages and Spanish, as well as members of the council.[62][91] In the Philippines,[92][93] with the Manila galleon, Nahuatl left an important mark on its languages,[94][95] such as Tagalog and Cebuano.[96][97]

In the Tlaxcaltec cities in Coahuila and Nuevo León, because Neo-Tlaxcaltec Nahuatl was the language in common use,[98][99] the members of the local government appointed a Nahuatlato, who was in charge of translating the agreements into minutes, copying laws and keeping books in the coffers.[67] Likewise, it is in this century when there is a greater written record of the Mexican language in San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala,[100] as evidenced by the large number of Nahua documents,[101][102] especially wills,[103][104] preserved from the 17th and 18th centuries.[105][106]

Regarding indigenous education, in 1697 the royal decree that revoked the prohibition of indigenous people to be ordained as priests was made, reiterating it in 1725. In this way, the king declared that indigenous people should be treated "according to and like the other vassals in my extensive domains of Europe, with whom they must be equal in everything."[65] At this time, the Tlaxcaltec governor Juan Ventura Zapata wrote the work in Nahuatl entitled Chrónica de la muy noble y leal ciudad de Tlaxcala, and with news until 1689. The last part of the Chrónica was written by the priest Manuel de los Santos y Salazar, who also wrote the play in Nahuatl entitled Invención de la Santa Cruz.[31][107]

King Philip V of Spain, faced with a series of problems related to Manuel José Rubio y Salinas' compliance with the royal decree of 1749 that ordered the secularization of doctrines, became aware of the opposition by indigenous people, Franciscans, Augustinians and the inhabitants of Mexico City, thus softening secularization. For this reason, he ordered that the new parish priests be "perfectly instructed in the languages of the natives and these in Spanish."[65] In 1754 another important grammar arises, this time by José Agustín de Aldama.

The philosopher Francisco Javier Clavijero, a Jesuit priest from New Spain, known mainly for his work Historia antigua de México,[108] studied and analyzed the language of Nahuatl poetry, describing it as "pure, entertaining, brilliant, figurative and full of comparisons with the most pleasant objects of the nature."[109]

In his time there were European writers stating that in the languages of America there were not enough words to express general notions and that metaphysical concepts could not be represented. Clavijero refutes that idea completely, pointing out that "there are few languages more capable of expressing metaphysical ideas than Mexicano, because it is difficult to find another in which abstract names abound so much."[109]

Decline period

1767–1821

This stage, considered by Garibay to be the time of "systematic decadence" or "dissolve", begins with the attempt of Cardinal Francisco de Lorenzana, archbishop of Mexico, to radicalize a change in state language policy on 6 October 1769, issuing a famous pastoral letter on the languages of New Spain, referring to them as "a contagious disease that separates the Indians from social intercourse with the Spaniards. It is a plague that perverts the dogmas of our Holy Faith."[14]

Among the causes of the beginning of the decadence, there are also the expulsion of the Jesuits two years earlier,[65] which led to the exile of a large number of scholars of the Aztec language, such as Clavijero himself, and the absolutist policy of the Bourbons with King Charles III of Spain, since power in the Spanish Empire was centralized trying to avoid bilingualism.[62] A decree of Charles III on 10 May 1770 established the creation of new educational centers completely in Spanish for the indigenous nobility and with this he tried to remove the classic Nahuatl as a literary language.[110]

From this decree, the idea began to spread among the people that one could only preach in Spanish. Rafael Sandoval, a priest who wrote the Arte de la lengua mexicana of 1810, records that the decree of King Charles III establishes "that the opinion was not and could not be that for now the peoples would be left without ministers of the language," along who also believes that those people spreading the idea of only preaching in Spanish "voluntarily close their eyes so as not to see on the same decree."[111]

The imposition of Spanish hardly affected the linguistic situation of the time. Therefore, it is inferred that the implementation of these policies was moderate.[14][112] In fact, Sandoval indicates that "before Mr. D. Carlos himself stated quite the opposite in the following year of 1777, endowing the chairs of Mexicano and Otomi languages in the Royal College of Tepotzotlan," showing a different attitude of the king seven years later of the decree.[111]

The indigenous and Nahuatl-speaking situation at the beginning of the independence movement had actually been sustained since 65% of the population was indigenous out of the 6 million inhabitants of the country and the Aztec language continued to be the lingua franca of New Spain.[113][114] Demographic indicators show a growth parallel to that of the mestizo population in Mexico. Furthermore, Spanish courts still admitted Nahuatl testimonies and documentation as evidence in trials, with court translators expounding in Spanish.

1821–1857

.png.webp)

Throughout modern times, the situation of indigenous languages has become increasingly precarious in Mexico, and the number of speakers of virtually all indigenous languages has decreased.[115][31] Although the absolute number of Nahuatl speakers has actually increased in the last century, indigenous populations have become increasingly marginalized in Mexican society.[116]

At this time the greater imposition of Spanish begins and discrimination against indigenous languages becomes common, since it is stigmatized in the way that society classifies speaking an indigenous language as "an Indian thing". The 1824 Constitution, while it could have been perfectly written in Nahuatl, was written in Spanish, precisely because those who wrote it were Spanish-speakers, although the Spanish language was not even the majority language at that time.[117]

At the beginning of the First Mexican Republic, the category of "Indians" was abolished, along with the rights, privileges and important administrative principles that it conferred at the community level in the Laws of the Indies. From this fact, the Mexican state sought the assimilation and extermination of indigenous peoples. As for assimilation, the Hispanicization strategy served to integrate indigenous people into the world labor market. From this, a mythical and glorified image of the indigenous past was idealized, but the modern indigenous was marginalized.[14]

In the 1830s, due to the need to want to build a united and modernized nation, the liberals José María Luis Mora and Valentín Gómez Farías were in favor of integrating the indigenous peoples and merging them with the masses in general and therefore proposed in the government acts that there was no distinction between "Indians" and "non-Indians", only having to resort to the words poor and rich. This would mean that, by not considering the indigenous people as their own entity, the cultural and linguistic division of the country would be ignored.[73]

On the other hand, there were those who promoted the use of native languages to remove the cultural barriers that separated the native peoples from the rest of the Mexican citizens. Among these, Vicente Guerrero, Carlos María de Bustamante and Juan Rodríguez Puebla. However, few were those who supported this idea, so it was not enough to change the language policy carried out in the first half of the century.[73]

The great changes in the indigenous communities occurred after the agrarian reforms that emerged from the Plan of Ayutla through the Lerdo law in the mid-19th century,[118] with which communal lands were abolished and from then on the indigenous were forced to pay a series of new taxes and that under the coercion of landowners and the government they could not pay, creating large latifundia, which caused them to gradually lose their land, their identity, their language, and even their freedom.

This process accelerated changes in the asymmetric relationship between indigenous languages and Spanish, thus Nahuatl was increasingly influenced and modified; As a first consequence, an area of rapid loss of speech and customs is observable, close to the big cities. As a second consequence, we see areas where Hispanicization is stronger, causing active bilingualism. In a third area, the indigenous speakers remained more isolated and kept their traditions purer. By the middle of the 19th century, speakers of indigenous languages were already 37% of the population.[14]

Modern era

1857–1910

During the Second Mexican Empire, Emperor Maximilian I tried to have a specialist translator in Nahuatl-Spanish because he was interested in the empire using the language spoken by a large part of the population,[119] so he devoted himself to learning the Aztec language and his translator, Faustino Chimalpopoca,[120] who belonged to the indigenous elite of the time, became his teacher and was part of the imperial government. In spite of everything, the Aztec language was not recognized as the official language of the Mexican Empire, although it did use it as a tool for territorial control in dispute against its rivals, the liberals.[121]

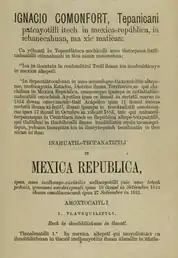

.svg.png.webp)

It was very important for Maximilian to issue his decrees in Nahuatl and Spanish, since he was aware that it was necessary to approach the citizens in their own language. In addition, the emperor acted as a protective father of the indigenous people, including them in his imperial project and protecting them under his tutelage, as they were used to being during the viceregal era. Therefore, Maximiliano idealized himself as the continuation of the Weyi Tlahtoani,[122] a title that he also includes in his decrees and edicts in Nahuatl.[120]

The French invaders, during the Second French Intervention, were interested in knowing all the details of the indigenous peoples of Mexico. One of the greatest interests of the French became Nahuatl, arguing that the Aztec language could be used to secure the objectives of the Mexican Empire. The study of Nahuatl was done mainly through the Scientific Commission of Mexico and the Literary and Artistic Scientific Commission of Mexico.[121]

In 1865, Maximilian I issued two bilingual decrees (in Mexicano and Spanish) and, on 16 September 1866, he issued an edict, also bilingual, on the legal estate in favor of the indigenous peoples.[120][123] At this time, the most influential Nahuatl was Faustino Chimalpopoca, who also taught Mexicano at the University of Mexico and wrote works with an educational purpose in the language, such as the Epítome o modo fácil de aprender el idioma nahuatl o lengua mexicana.[124]

His influence was important in the government, since the emperor wrote of him that "his affection for the Empire, his indigenous origin and his knowledge of the Aztec language would greatly facilitate his task of attracting the inhabitants of the Sierra de Querétaro and making them defend the Empire actively." Likewise, he became the official interpreter to listen to requests and complaints of indigenous people in the imperial court.[121]

One of the French people in charge of the studies by the Scientific Commission of Mexico was Brasseur de Bourbourg. In his research he also benefited from the knowledge of Faustino Chimalpopoca. As for the Literary and Artistic Scientific Commission of Mexico, all its leaders were Nahuatlatos (Nahuatl speakers). The president José Fernando Ramírez, the vice president Francisco Pimentel and the member Faustino Chimalpopoca stand out. On the other hand, Maximilian's advisors, also Nahuatlatos, were members of the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics, among them, Manuel Orozco y Berra, Pimentel and Chimalpopoca.[121]

Several years after the fall of the Second Empire, the government of President Porfirio Díaz and the Porfirian policies tended to eliminate the native languages, seeking the development and progress of the country under Mexican nationalism. However, the Díaz regime paid attention to indigenous culture in a classical way, continuing to privilege the ancient culture and ignore the contemporary. During this time, Mexican intellectuals sought to make a standard grammar of the Aztec language based on Central Nahuatl variants for writing and spelling.[2]

An achievement in its time was the translation of the 1857 Constitution into Nahuatl by Miguel Trinidad Palma,[125] thus becoming the first Mexican constitution to be available in Nahuatl and, in general, in a vernacular language.[31] In this last quarter of the 19th century, there is still evidence of Neo-Tlaxcaltec Nahuatl-speaking families in municipalities of Nuevo León, mainly in Guadalupe and Bustamante.[126] However, at this time, the percentage of native language speakers had already decreased to 17% in the national territory.[14]

The loss of autonomy of the Neotlaxcalans in Coahuila also led to the loss of Nahuatl as a common language in San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala.[127] Don Cesáreo Reyes, a Nahuatl native of San Esteban, explained that when he studied at the town school he was an assistant to several teachers who were not Nahuatl speakers, since they were giving classes to students who did not know Spanish.[100] This is added to the number of testimonies that show that Castilianization actually occurred in independent Mexico and through the educational system, with the aim of erasing indigenous identity.[114]

Abroad, interest in the study of the Aztec language also grew thanks to authors such as the French lexicographer Rémi Siméon, who published the Dictionary of the Nahuatl or Mexicano language in Paris in 1885.[31] From 1883 to 1889 he published various studies and translations of the Anales o crónicas of Chimalpahin.

Other foreigners who participated in the study of the language were Johann Karl Eduard Buschmann, Eduard Georg Seler and Daniel Garrison Brinton. All of them published Nahua texts with their translations into languages such as English and German. In Mexico, the Nahuatlatos Antonio Peñafiel, Cecilio Robelo and Francisco del Paso y Troncoso stand out. The latter, who was a Mexican historian, professor of Nahuatl and director of the National Museum of Archaeology, History and Ethnology, rediscovered, published and made known a large number of documents and works written in the language such as the Legend of the Suns.[31]

In 1902, intellectuals such as Justo Sierra Méndez proposed that compulsory instruction in Spanish was necessary for the integration of native peoples into national society. Justo Sierra stated that "being the only school language, it will stunt and destroy local languages and thus the unification of the national speech, an invaluable vehicle for social unification, will be a fact." On the other hand, Francisco Belmar, a lawyer and linguist, founded La Sociedad Indianista, bringing together linguists and anthropologists who studied and fought to maintain indigenous languages.[73]

1910–1980

With the Mexican Revolution, an indigenist revival develops, appreciating the intellectual culture, specifically oral literature, of the original peoples in Mexico.[31] Nahuatl stands out for its interest in linguistic research. On the other hand, the educational system of the 20th century became responsible for the massive linguistic displacement of indigenous languages.[114] The revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, after several years fighting in the Mexican Revolution, issued two manifestos in Nahuatl on 27 April 1918.[128]

In 1919, Manuel Gamio, the father of modern anthropology in Mexico, carried out an enormous investigation, recovering testimonies from the oral literature of the Teotihuacán Valley, among other things, together with the linguist Pablo González Casanova.[129] In addition, it was postulated that, to carry out this type of work, it was essential to know the Nahuatl language.[31] On the other hand, in the educational field, Gregorio Torres Quintero, author of the Rudimentary Instruction Law, was against using a vernacular language for teaching Spanish.[73] In 1926, José Manuel Puig Casauranc started a project called Casa del estudiante indígena, with the aim of encouraging the preservation of the spoken language while learning Spanish. Later, with Narciso Bassols in the SEP, a focus on rural education began to develop.[73]

From the 1930s, a phonological valorization of the Nahuatl language began and an effort was made to write and regulate it based on its own characteristics, which is known as "modern writing" and which began to be promoted in education from the second half of the 20th century,[130] contrary to the way of writing Mexican used in classic texts, the "traditional writing".[131] Only until 1934, with the government of President Lázaro Cárdenas, did a true institutional interest arise in understanding and studying indigenous culture, trying to reverse the trend of forced incorporation into national culture, which in fact did not happen and the loss continued until the eighties.

In 1936 the Department of Indian Affairs was created with the aim of supporting rural peoples. To teach the towns to read and write, young people who knew how to speak a little Spanish and their mother tongue, Nahuatl, were hired, giving them a half-year course on teaching to establish Spanish as the only language when they returned to their communities of origin.[132]

The Tlalocan magazine, founded by R. H. Barlow, an American expert in the Nahuatl language,[133] and George T. Smisor,[134] began to be published physically in 1943.[135] Years later, Fernando Horcasitas, a member of the UNAM Anthropological Research Institute, took over as editor together with Ignacio Bernal. When the latter resigned in the VII edition, Horcasitas requested the support of Miguel León-Portilla, with whom he began to edit the magazine in the following editions, joining Karen Dakin several years later.[136]

In the early 1950s, R. H. Barlow and Miguel Barrios Espinosa, a Nahua educator,[137] created the Mexihkatl Itonalama, a Mexicano-language newspaper that circulated in several towns in the states of Mexico, Puebla, and Morelos. In this a new orthography appears for the first time to write the language. In fact, the first issue of the newspaper included a section on writing.[138]

The Mexihkatl Itonalama also published poems, historical essays, narratives, and even an edition of a short comedy titled Se Ixewayotl san ika se Ixpantilistli, which was originally written in the 17th century. The best-known narrative in this newspaper is entitled Tonatiw iwan meetstli, dictated to R. H. Barlow in 1949 by a Nahua from Miahuatlán, Puebla, named Valentín Ramírez.[139]

A new study and evaluation of texts in the Aztec language with a humanistic sense began with Ángel María Garibay, a Mexican philologist and historian,[31] author of books that have served as a reference to date, among them, Historia de la literatura náhuatl, Llave del náhuatl, Poesía náhuatl, Épica náhuatl and Panorama literario de los pueblos nahuas. He also edited works such as the General History of the Things of New Spain by Sahagún and Diego Durán's History of the Indies of New Spain.

1980-today

Significant changes have taken place since the mid-1980s, although educational policies in Mexico have focused on the Hispanicization of indigenous communities, to teach purely Spanish and discourage the use of native languages,[140] resulting in today's good number of Nahuatl speakers are able to write both their language and Spanish; even so, its Spanish literacy rate remains well below the national average.

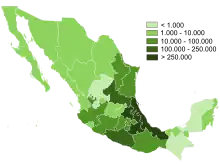

Despite the forced Hispanicization,[114] Nahuatl is still spoken by more than two million people, of which around 10% are monolingual. The survival of Nahuatl as a whole is not in imminent danger, but the survival of certain dialects is; and some have already become extinct during the last decades of the 20th century.[141][142] Today it is spoken primarily in rural areas by a lower class of indigenous subsistence farmers. According to the INEGI, 51% of Nahuatl speakers are involved in the agricultural sector and 6 out of 10 do not receive wages or earn less than the minimum wage.

In 1982, at the initiative of the Organization of Nahua Indigenous Professionals A.C. (OPINAC) and students and linguists of the General Directorate of Indigenous Education (DGEI), a general consensus was reached in the city of Pátzcuaro on writing, developing a "practical orthography", which was used since then by the Ministry of Public Education (SEP) for bilingual education.[132]

A year later, Alonso López Mar, Hermenegildo Martínez, and Delfino Hernández, all Nahua teachers from La Huasteca, wrote four-volume grammars of Mexicano whose title is Nahuatlahtolmelahualiztli ("The correct form of the Nahuatl language"). The edition of the SEP made a circulation of more than 25 thousand copies, taking a big step in the current flourishing of the language. That same year, Delfino Hernández received the first prize in the Nahuatl Story Contest with the story Xochitlahtoleh.[31]

In Tlaxcala, during that decade, the governors publicly boasted that they were on the road to progress because, according to them, there were no longer Nahua speakers in the state. If there was 80% of Nahua-speaking population in the state before 1910, today that number is below 5%. This also indicates that the institutions had an erroneous criterion to consider an indigenous population, the language. In this way, the language was lost in the following generations, so, in reality, the inhabitants of today are the descendants of those Nahuas.[143]

In 1985, Natalio Hernández, also known by his pseudonym José Antonio Xokoyotsij, is a Nahua intellectual and poet who founded the Association of Writers in Indigenous Languages (AELI), among other institutions. He wrote several works, among these, perhaps the most important is his book of Nahuatl poetry entitled Xochikoskatl.[144] Likewise, he published in several magazines, such as Nahuatl Culture Studies.[31]

The 1990s saw the appearance of diametric changes in the policies of the Mexican government towards indigenous and linguistic rights. The evolution of agreements in the field of international rights[145] combined with internal pressures led to legislative reforms and the creation of decentralized government agencies; thus, by 2001 the National Indigenous Institute disappeared to make way for the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI) created in 2003 with responsibilities for the promotion and protection of indigenous peoples. indigenous languages.[146]

In particular, the General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples[147] recognizes all of the country's indigenous languages, including Nahuatl, as "national languages" and gives indigenous people the right to use them in all spheres of public and private life. In article 11, which guarantees access to compulsory, bilingual and intercultural education.[148] This law gives rise to the Catalog of National Indigenous Languages in 2007.[149] In 2008, the then mayor of Mexico City, Marcelo Ebrard, expressed his support for the learning and teaching of Nahuatl for all city employees and those who work in the local public administration.[150][151]

In 2016, the first monolingual Nahuatl dictionary (in its Huasteca variant) was published by the Institute of Ethnological Teaching and Research of Zacatecas (IDIEZ),[152] a civil association founded in 2002 based in Zacatecas that promotes the revitalization, research and teaching of the Nahuatl language,[153] in conjunction with the University of Warsaw. The dictionary, titled Tlahtolxitlauhcayotl, contains 10,500 entries, and was co-authored by John Joseph Sullivan with native speakers of Mexicano.

In that same year, a proposal for an abugida or alphasyllabary of Nahuatl was formulated by Eduardo Tager and translated into Spanish in an article.[154] Although it has not been disseminated among teachers and Nahuatlatos, the proposal is more precise in terms of the adaptation of Nahua phonemes to writing than the Latin alphabet has been, and it has a better economy of space.

In 2018, Nahua peoples from 16 states in the country began collaborating with INALI creating a new modern orthography called Yankwiktlahkwilolli,[155] designed to be the standardized orthography of Nahuatl in the coming years.[156][157] The modern writing has much greater use in the modern variants than in the classic variant, since the texts, documents and literary works of the time usually use the Jesuit one.[158]

In recent years, the language is gaining more and more popularity, a fact that has led to the increase of content on the internet in the language and the translation of websites such as Wikipedia and applications such as Telegram Messenger into Nahuatl. In addition, there are radio stations that broadcast in Nahuatl in the five states of Mexico with more Nahuatl speakers.[159] On the other hand, due to migration in recent decades, communities of Nahua speakers have been established in the United States.

In 2020, the Chamber of Deputies approved the opinion with a draft decree that recognizes Spanish, Mexicano and other indigenous languages as official languages, which would have the same validity in terms of the law.[160] A year later, the Senate of the Republic approved the reform of article 2 of the Mexican Constitution, recognizing Spanish, Mexicano, Maya and 66 other languages as official.[161]

See also

References

- Based in Lastra de Suárez 1986; Fowler 1985.

- "Aportaciones educativas en el área de lenguas" (PDF).

- "Duverger, Christian. – El Primer Mestizaje (2007)".

- "Gramática moderna del nahua de la Huasteca" (PDF).

- Canger (1980, p. 12)

- Kaufman (2001, p. 1)

- Kaufman 2001, pp. 3–6, 12

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee (1937). "The origin of Aztec tl". American Anthropologist. 39 (2): 265–274. doi:10.1525/aa.1937.39.2.02a00070.

- Campbell, Lyle; Langacker, Ronald (1978). "Proto-Aztecan vowels: Part I". International Journal of American Linguistics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 44 (2): 85–102. doi:10.1086/465526. OCLC 1753556. S2CID 143091460.

- For example, Florescano (2017, p. 55), when reviewing the city from the mythical and cosmogonic in the post-classical Nahua traditions (c. 900–1521).

- Hers, 1993: 107

- Kaufman, 1976; Whittaker, 2012: 55.

- Díaz, 2018: § 8; Rodríguez, A. M. (7 July 2011). "Hallan en glifos de Teotihuacán un avanzado sistema de escritura". México. p. 4.

- Brylak, Agnieszka; Madajczak, Julia; Olko, Justyna; Sullivan, John (23 November 2020). Loans in Colonial and Modern Nahuatl. De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110591484. ISBN 978-3-11-059148-4. S2CID 229490818.

- Kaufman, 2001: 6-7; Whittaker, 2012: 55.

- Manzanillla, 2005.

- Kaufman (2001)

- "Mesoamerican Lexical Calques in Ancient Maya Writing and Imagery" (PDF).

- López Austin & López Luján, 1998

- "Compilacion – Produccion de Textos Xi'iuy – Tenek y Nahuatl 2018 PDF | PDF | Multilingüismo | Alimentos". Scribd. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- Carrasco, 1979.

- A fact widely accepted by researchers, as an example we take Brundage, 1982: 28.

- "El nombre náhuatl de la Triple Alianza" (PDF).

- Canger, 2011

- Canger, U. (2011). El nauatl urbano de Tlatelolco/Tenochtitlan, resultado de convergencia entre dialectos: con un esbozo brevísimo de la historia de los dialectos. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, 42, 246–258.

- More markedly it is named “mexihkatekpillahtolli”; the elegant speech of the Aztec nobles.

- Paredes, 1979:93

- "Los nahuas y el náhuatl, antes y después de la conquista".

- In speech it is rather used of the word-expression "masewalkopa"; speak in the manner of the townspeople.

- "CIALC – 404". www.cialc.unam.mx. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- "Literatura en náhuatl clásico y en las variantes de dicha lengua hasta el presente – Detalle de Estéticas y Grupos – Enciclopedia de la Literatura en México – FLM – CONACULTA". www.elem.mx. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- León-Portilla, 1983: 63–70

- López Corral, Aurelio (2011). "Los glifos de suelo en códices acolhua de la Colonia temprana: un reanálisis de su significado". Desacatos (in Spanish) (37): 145–162. doi:10.29340/37.293. ISSN 1607-050X. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- 50 años. Centro de Estudios de Historia de México Carso. Fundación Carlos Slim. 2015. p. 133. ISBN 978-607-7805-11-3.

- "Tribute Roll". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- Lacadena, Alfonso (2008). "A Nahuatl Silabary" (PDF). The Pari Journal: 23.

- de las Casas, Bartolomé (1555). Apologética historia.

- Zender, Marc. "One Hundred and Fifty Years of Nahuatl Decipherment" (PDF). The PARI Journal.

- "Pedro de Gante | Real Academia de la Historia". dbe.rah.es. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- "Adaptar la lengua, conquistar la escritura. El náhuatl en la evangelización durante el siglo XVI".

- Aidé Morín González (2005). "Catecismo testeriano: una lectura de evangelización" (PDF). XVIII Encuentro de Investigadores del Pensamiento Novohispano. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- "Catecismo Testeriano". 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- María, Fundación Santa; Criado, Buenaventura Delgado (1 January 1993). Historia de la educación en España y América (in Spanish). Ediciones Morata. ISBN 978-84-7112-376-3.

- León-Portilla. "Estudio introductorio". 2002

- "La Política Lingüística en la Nueva España".

- James Lockhart, We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico, translated and edited. University of California Press, 1991, pp. 42.

- S.L. Cline, The Book of Tributes, translator and editor. UCLA Latin American Center Publications, Nahuatl Studies Series 1993.

- Anales de Tlatelolco. Rafael Tena INAH-CONACULTA p 55 73

- Matthew, Laura E.; Romero, Sergio F. (2012). "Nahuatl and Pipil in Colonial Guatemala: A Central American Counterpoint". Ethnohistory. 59 (4): 765. doi:10.1215/00141801-1642743. ISSN 0014-1801.

- Matthew, Laura (1 January 2000). "El náhuatl y la identidad mexicana en la Guatemala colonial". Mesoamérica. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- "México: La enseñanza del náhuatl en Guadalajara | Servindi – Servicios de Comunicación Intercultural". www.servindi.org. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- Alonso de la Fuente, José Andrés (1 December 2007). "Proto-maya y lingüística diacrónica. Una (breve y necesaria) introducción". Journal de la Société des américanistes (in Spanish). 92 (93–1): 49–72. doi:10.4000/jsa.6383. ISSN 0037-9174. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Instituto Cervantes (ed.). Traductores e intérpretes en los primeros encuentros colombinos (PDF).

- "Antonio Valeriano ¿autor del Nican Mopohua?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012.

- Burrus, Ernest J. (1981). The Oldest Copy of the Nican Mopohua (La copia más antigua del "Nican Mopohua"). Cara Studies in Popular Devotion (Washington D.C.: Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (Georgetown University)). II, Guadalupan Studies (4). OCLC 9593292

- Ernest J. Burrus (Ernest Joseph Burrus: 1907 – 1991): historiador jesuita del Virreinato de Nueva España, sobre todo de lo concerniente a Sonora y a la Península de la Baja California.

- CARA: Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (Centro de Investigación Aplicada al Apostolado), de la Universidad de Georgetown.

- "Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España, segundo libro". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

- Bowles, David (7 July 2019). "La monarquía hispánica y el náhuatl". Medium. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Wright-Carr, David (1 September 2007). "La política lingüística en la Nueva España". Acta Universitaria (in Spanish). 17 (3): 5–19. doi:10.15174/au.2007.156. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- "La ensenanza de las lenguas indígenas en la Real y Pontificia Universidad de México".

- "Dios itlaçonantzine". Graphite Publishing. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Brylak, Agnieszka (2016). "Some Remarks on Theteponazcuicatlof the Pre-Hispanic Nahua". Ancient Mesoamerica. 27 (2): 429–439. doi:10.1017/S095653611600002X. ISSN 0956-5361. S2CID 164747814.

- "Multiglosia virreinal novohispana: el náhuatl" (PDF).

- "General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. "The work of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590)". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "La educación indígena en el siglo XVIII". biblioweb.tic.unam.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "San Esteban de la Nueva Tlaxcala. La formación de su identidad colonizadora" (PDF).

- "Saltillo Mágico 2 | PDF | Nueva españa | Religión y creencia". Scribd. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Historia de una casa real. Origen y ocaso del linaje gobernante en México-Tenochtitlan".

- Chang-Rodríguez, Raquel, Op.cit. capítulo "Los cronistas indígenas" de José Rubén Romero Galván, p.274-278

- Mcpheeters, D. W. (1954). "An Unknown Early Seventeenth-Century Codex of the Crónica Mexicana of Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 34 (4): 506–512. doi:10.2307/2509083. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2509083.

- Schroeder, Susan (August 2011). "The Truth about the Crónica Mexicayotl". Colonial Latin American Review. 20 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1080/10609164.2011.587268. S2CID 162390334.

- Almost all the biographies suppose it or assure it. Vázquez Chamorro says that he could not be, as he did not master the Latin language, a requirement of the position; According to this author, if documents are preserved that seem to suggest his Nahuatlato status, it is because he acted in the Royal Court and other forums as a representative of Aztec nobles, but without being an official.

- "La política lingüística en México entre Independencia y Revolución (1810–1910)" (PDF).

- "Consideraciones generales de la política lingüística de la Corona en Indias" (PDF).

- Brylak, Agnieszka; Madajczak, Julia; Olko, Justyna; Sullivan, John (2020). Cross-cultural transfer as seen through the Nahuatl lexicon. doi:10.1515/9783110591484. ISBN 9783110591484. S2CID 229490818.

- Morales Abril, O. (2013). Gaspar Fernandez: su vida y obras como testimonio de la cultura musical novohispana a principios del siglo XVII. Enseñanza y ejercicio de la música en México. Arturo Camacho Becerra (ed.). México DF, CIESAS, El Colegio de Jalisco y Universidad de Guadalajara, 71–125.

- "Conformación y retórica de los repertorios musicales catedralicios en la Nueva España" (PDF).

- Abril, Omar Morales (2013). "Gaspar Fernández: su vida y obras como testimonio de la cultura musical novohispana a principios del siglo XVII". Ejercicio y enseñanza de la música. Oaxaca: CIESAS: 71–125.

- "#LingüísticaAGN el aprendizaje del otomí en la Nueva España".

- "UNAM IIH – Primera, segunda, cuarta, quinta y sexta relaciones de las Différentes histoires originales".

- "Un nuevo manuscrito de Chimalpahin" (PDF).

- León-Portilla, Miguel (1 April 1981). "La Embajada de los japoneses en México, 1614. El testimonio en náhuatl del cronista Chimalpahin". Estudios de Asia y África (in Spanish): 215–241. ISSN 2448-654X. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Carochi, Horacio (1983). Miguel León Portilla (ed.). El arte de la lengua mexicana. Edición facsimilar (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 9685805865.

- León Portilla, Miguel (1983). Miguel León Portilla (ed.). Estudio introductorio a Arte de la Lengua Mexicana de Horacio Carochi (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. p. XIII. ISBN 9685805865.

- "Las artes de lenguas indígenas. Notas en torno a las obras impresas en el siglo XVIII - Detalle de Estéticas y Grupos - Enciclopedia de la Literatura en México – FLM – CONACULTA". www.elem.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Sor Juana y sus versos amestizados en una sociedad variopinta – La Lengua de Sor Juana" (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Literatura y Tradición Oral". comunidad.ulsa.edu.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Transmisora de lo Popular". www.razonypalabra.org.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Cervantes, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de. "El "Tocotín" en la loa para el Auto "El Divino Narciso" : ¿Criollismo sorjuanino? / Armando Partida Tayzan". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Aguirre Beltrán, 1983: 58–59.

- "Crónicas nahuas de Guatemala: El título de Santa María Ixhuatán (s. XVII) | New Media New Media" (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "¿En Filipinas también se habla náhuatl?". Matador Español (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Taladoire, Éric (3 January 2018). De América a Europa: Cuando los indígenas descubrieron el Viejo Mundo (1493–1892) (in Spanish). FCE – Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 978-607-16-5340-6.

- https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/manila-bulletin/20170629/281771334204459. Retrieved 21 June 2022 – via PressReader.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Albalá, Paloma (1 March 2003). "Hispanic Words of Indoamerican Origin in the Philippines". Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. 51 (1): 125–146. ISSN 2244-1638.

- "Love Mexican-Filipino Style". San Miguel Times. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Lenguas en contacto: Influencias léxicas del español en el tagalo, el chabacano, el chamorro y el cebuano".

- "Historia del Nuevo Reino de León 1577–1723" (PDF).

- "El Sur de Coahuila en el siglo XVII" (PDF).

- Moreno, W. Jiménez (27 September 2016). "El náhuatl de los tlaxcaltecas de San Esteban de la Nueva Tlaxcala". Tlalocan. 3 (1): 84–86. doi:10.19130/iifl.tlalocan.1949.354. ISSN 0185-0989.

- "Levels of acculturation in northeastern New Spain; San Esteban testaments of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries" (PDF).

- "Temas del Virreinato. Documentos del Archivo Municipal de Saltillo" (PDF).

- "The Nahuatl Testaments of San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala (Saltillo)". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.492.3310.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Historias de protección y depredación de los recursos naturales en el Valle de Saltillo y la Sierra de Zapalinamé" (PDF).

- Celestino, Eustaquio (1991). El Señorío de San Esteban del Saltillo: voz y escritura nahuas, siglos XVII y XVIII (in Spanish). Archivo Municipal de Saltillo. ISBN 978-968-6686-00-5.

- Offutt, Leslie Scott (Jan 2018), "Puro tlaxcalteca? Ethnic Integrity and Consciousness in Late Seventeenth-Century Northern New Spain," The Americas,, Vol 75, No. 1, pp. 32-33, 40-45

- "Invención de la Santa Cruz".

- Luis Villoro, "4. Francisco Javier Clavijero", en Los grandes momentos del indigenismo en México, México, El Colegio de México-El Colegio Nacional-Fondo de Cultura Económica, s/f, pp. 113–152.

- "Estudio de la filosofía y riqueza de la lengua mexicana" (PDF).

- Aguirre Beltrán, 1983:64

- "Arte de la lengua mexicana" (PDF).

- "Castellanización y las escuelas de lengua castellana durante el siglo XVIII – Detalle de Estéticas y Grupos – Enciclopedia de la Literatura en México – FLM – CONACULTA". www.elem.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Aguirre Beltrán, 1983: 11

- Mexico.com (10 August 2018). "Así desaparecen las lenguas indígenas en México: "Me daban golpes en la mano por no hablar castellano en la escuela"". ElDiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Yásnaya Aguilar: México es una nación artificial". Corriente Alterna (in Spanish). 26 February 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Empire, Colony, and Globalization. A Brief History of the Nahuatl Language" (PDF).

- "Error, llamar Conquista a caída de México Tenochtitlan: Navarrete". Grupo Milenio (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Aguirre Beltrán, 1983: 81

- "El indigenismo de Maximiliano en México (1864–1867)".

- Horcasitas, Fernando (27 September 2016). "Un edicto de Maximiliano en náhuatl". Tlalocan (in Spanish). 4 (3): 230–235. doi:10.19130/iifl.tlalocan.1963.330. ISSN 0185-0989.

- Bañuelos, Jesús Francisco Ramírez (21 April 2021). "El control territorial mediante el uso de la lengua náhuatl en el Segundo Imperio mexicano". Pacha. Revista de Estudios Contemporáneos del Sur Global (in Spanish). 2 (4): 67–77. doi:10.46652/pacha.v2i4.48. ISSN 2697-3677. S2CID 235505245.

- Ramírez Bañuelos, Jesus (12 December 2021). "La tutela imperial de los índigenas en el Segundo Imperio Mexicano". Acta Hispanica (in Spanish): 43–61. doi:10.14232/actahisp/2021.26.43-61. S2CID 245225474. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- "Lenguas indígenas y Maximiliano el legislador".

- Galicia Chimalpopoca, Faustino. Epítome o modo fácil de aprender el idioma nahuatl o lengua mexicana (in Spanish).

- «Inahuatil-Tecpanatiztli in Mexica Republica (1857)».

- "La herencia tlaxcalteca". bibliotecadigital.ilce.edu.mx. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "San Esteban, el pueblo". Grupo Milenio (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Manifestos en Nahuatl de Emiliano Zapata, Abril 1918 – Xinachtlahtolli". Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Pablo González Casanova".

- Beltrán, 1983:216–218; 259–261.

- Garibay, 2001:25; "As long as there is no wisely determined uniformity, by whoever takes into account all the data, both phonic and graphic, and, in addition, the competent authority to impose a new system, it is comfortable to continue using the system that can be called traditional, however deficient it may be." Note that Garibay wrote this in 1940.

- "Estrategias de alfabetización en lengua náhuatl para profesores en servicio de educación primaria indígena" (PDF).

- "Robert H. Barlow, de albacea de Lovecraft a mesoamericanista que difundió el náhuatl". cronica.com.mx (in Spanish). 28 July 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Yancuic tlahtolli: la nueva palabra. Una antología de la literatura náhuatl contemporánea" (PDF).

- "Tlalocan: revista de fuentes para el conocimiento de las culturas indígenas de México". www.unamenlinea.unam.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Tlalocan". www.revistas.unam.mx (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Mexihkatl itonalama. M. Barrios Espinosa. 1950.

- "Mexihkatl Itonalama – Xinachtlahtolli". Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Tonatiw iwan meetstli. El sol y la luna" (PDF).

- "La pérdida de la lengua náhuatl | Las comunidades indígenas en América latina". campuspress.yale.edu. Retrieved 21 June 2022.