History of Savannah, Georgia

The city of Savannah, Georgia, the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, was established in 1733 and was the first colonial and state capital of Georgia.[1] It is known as Georgia's first planned city and attracts millions of visitors, who enjoy the city's architecture and historic structures such as the birthplace of Juliette Gordon Low (founder of the Girl Scouts of the United States of America), the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences (one of the South's first public museums), the First African Baptist Church (one of the oldest black Baptist congregations in the United States), Congregation Mickve Israel (the third-oldest synagogue in America), and the Central of Georgia Railway roundhouse complex (the oldest standing antebellum rail facility in America).[1][2] Today, Savannah's downtown area is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the United States (designated in 1966).[A] [1]

History

Native settlers

European encroachment Although Savannah was the first permanent colonial settlement in modern-day Georgia, it was far from the first European encroachment into Yamasee/Creek/Guale lands. As early as the 16th century, Spanish missions and presidios (military outposts) were established all along the Georgia coast. Spanish missions such as Santa Catalina de Guale and Santo Domingo de Talaje, attacked and weakened by the Guale revolt of 1597, were finally abandoned by the 1680s as a result of continuous encroachment by traders from the Carolina Lowcountry. Hoping to capitalize on the power vacuum created by the Spanish withdrawal to Florida, the Crown allied itself with the native bands on the Georgia coast, such as the Yamasee, a relatively new Indian group made up of remnants of earlier groups including the Guale.

|

The Yamacraws, a Native American tribe, were the first known people to settle in and around Savannah. In the 18th century, under their leader Tomochichi, they met the newly arriving European settlers.

Oglethorpe's arrival and the establishment of a colony

Much has been written about Oglethorpe, his reputation as a reformer and his friendship with the Yamasee and Creek peoples. However, it should be stressed that the alliance between the Yamasee and the colonists was tenuous at best. Earlier in the 18th century the Yamasee, having become deeply indebted to Carolinian traders, were increasingly convinced that this debt would be paid through their enslavement. The Yamasee War of 1715–1717 left the Yamasee weakened and opened their lands to settlement; the conflict ultimately enabled the successful colonization of the Georgia coast.

|

In November 1732 the merchantman Anne, carrying 114 colonists (including General James Oglethorpe), set sail to the Americas.[3] On February 12, 1733,[4] after a brief stay at Charles Town, South Carolina, Oglethorpe and his settlers landed at Yamacraw Bluff and were greeted by Tomochici, the Yamacraws, and John and Mary Musgrove, Indian traders. (Mary Musgrove often served as an interpreter.) The city of Savannah was founded on that date, along with the Province of Georgia. Because of the friendship between Oglethorpe and Tomochici,[3] Savannah was able to flourish unhindered by warfare with Native American tribes that marked the beginnings of many early American colonies. In July 1733, five months after the arrival of the Anne, 41 Jews from the Sephardi community in London arrived in Savannah, the largest such group to enter a colony up to that time.[5]

Growth of the colony

Prior to arriving in America, Oglethorpe developed an elaborate plan for the growth of towns and regions within the framework of a sustainable agrarian economy and the challenges presented by an often hostile frontier. Features of the plan, now known as the Oglethorpe Plan, especially as it relates to town planning, have been preserved in Savannah, as well as in Darien, Georgia and at Fort Frederica National Monument.[6]

Although religious toleration was beginning to emerge as a value during the Enlightenment, it was the pragmatic need to attract settlers that led to broad religious freedoms. South Carolina wanted German Lutherans, Scottish Presbyterians, Moravians, French Huguenots and Jews as a counter to the French and Spanish Catholic absolutist presence to the south, which was perceived by Georgian settlers as a threat to the freedoms they had traditionally held.[7]

After Georgia became a royal colony (1754), there were so many dissenters (Protestants of minority, non-Anglican denominations) that the establishment of the Church of England was successfully resisted until 1752. These dissenting churches were the mainstay of the American Revolutionary movement that culminated in a war for independence from the British Crown. Through the patriotic and anti-authoritarian sermons of their ministers, these churches fostered and organized rebellion. Whereas the Anglican Church tended to preach stability and loyalty to the Crown, Protestant sects preached heavily from the Old Testament, with its emphasis on freedom and equality of all men before God, and the moral responsibility to rebel against tyrants.[8]

Over the next century and a half, Savannah welcomed numerous European immigrants; these included the Irish, the French, Greeks and others.

In 1740 George Whitefield founded the Bethesda Orphanage, which is now the oldest extant orphanage in the U.S.

Solomon's Lodge was founded in 1734 by James Oglethorpe, and it is considered to be the oldest continuously operating Masonic Lodge in North America.[9][10][11] Originally called simply the Lodge of Savannah, it was officially renamed Solomon's Lodge in 1776.[12]

Province of Georgia

The great experiment came to an end after Savannah and the rest of Georgia became a Royal Colony in 1754. Entrepreneurs and slaves were brought into the struggling colony, and Savannah was made the colonial capital of Georgia. The low marshes were converted into wild rice fields and tended by skilled slaves imported from West Africa (where these strains of rice had been grown by European colonists, who brought rice from its native Southeast Asia. However, attempts to establish a rice industry in Africa failed). The combination of European agricultural technology, and African labor, proved to be of great benefit for the city.

Initially, Creek groups gradually ceded lands to European settlers. In 1763 the Creeks agreed to the first of several large land cessions. This first agreement gave Georgia the land between the Savannah and Ogeechee rivers, south of Augusta, along with coastal land between the Altamaha and St. Marys rivers. An additional two million acres (8000 km2) of land between the Ogeechee and Altamaha rivers and the headwaters of the Oconee and Savannah rivers was ceded to Georgia by the Creeks and Cherokees in 1773.

Additional fortune came to the city in 1763 following the Treaty of Paris, which opened the interior of North America to economic interests in the American colonies. This was an important milestone in the development of Savannah, as it marks the beginning of economic ties to the interior. Trade, particularly the trade of deerskins, flourished along the upper Savannah River where skins were sent to Augusta and finally through Savannah for export to Europe. The establishment of a trading network on the Savannah River also curtailed Charleston's monopoly on the South Atlantic deerskin trade. Between 1764 and 1773 Savannah exported hides from 500,000 deer (2 million pounds), which established the city as a significant commercial port on the South Atlantic coast.

American Revolution

Savannah and the American Revolution For additional information you may also want to view the following articles:

|

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1778 during the American Revolutionary War, Savannah came under British and Loyalist control.[13] At the Siege of Savannah in 1779, American and French troops fought unsuccessfully to retake the city.

Late 18th/Early 19th century

On January 27, 1785, members of the State Assembly gathered in Savannah to found the nation's first state-chartered, public university—the University of Georgia (in Athens). In 1792 the Savannah Golf Club opened within a mile of Fort Jackson, on what is now President Street. It is the first known American golf club. In 1804 Candler Hospital was founded, and is the second oldest hospital in America in continuous operation.

On January 11, 1820, a fire broke out and burned a large section of the city, bringing nationwide attention to Savannah.[14]

A yellow fever epidemic struck Savannah in 1854, killing 650 residents.[15] Another followed in the summer of 1876, believed to have originated in the city, specifically from J. W. Schull, a sailor who was taken ill on July 23 and died seven days later.[16]

American Civil War

Savannah and the Civil War For additional information on Savannah and the American Civil War, you may wish to view the following articles:

|

I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.

— General William Tecumseh Sherman in a telegraphed message to President Abraham Lincoln

In November 1864, two months after capturing the city of Atlanta, General William Tecumseh Sherman and his army of 62,000 men began the march south to Savannah. They lived off the land and, by Sherman's own estimate, caused more than $100 million in property damage in Georgia alone.[17] Sherman called this harsh tactic of material war "hard war" (in modern times known as total war).[18]

Sherman and his troops captured Savannah on December 22, 1864. Sherman then telegraphed his commander-in-chief, President Abraham Lincoln, offering him the city as a Christmas present.

Late 19th century

| President Grover Cleveland and his entourage paid a visit to Savannah in February 1888. Cleveland visited the new Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences gallery and officiated at the ceremony dedicating a monument of Revolutionary War hero Sergeant William Jasper. A 21-gun salute was given by the Chatham County artillery to honor the commander-in-chief.[19] |

As the 19th century progressed, Savannah's population increased slightly and its wealth exponentially, but its ranking among the largest U.S. cities steadily dropped. The city went from 41st most populous city in 1860 to 62nd in 1880 (the first year Atlanta exceeded Savannah as Georgia's largest city). Savannah was the 86th largest city in 1910, and by 1930 it was no longer ranked in the top 100 most populous U.S. cities. Savannah State University was founded in 1890 and is the oldest African-American public college in Georgia.[20]

20th century

On 5 February 1958, during a training mission flown by a B-47, a Mark 15 nuclear bomb, also known as the Tybee Bomb, was lost off the coast of Tybee Island near Savannah. The bomb was thought by the Department of Energy to lie buried in silt at the bottom of Wassaw Sound.[21]

In December 1986, an oil tanker docked at the port of Savannah caused an oil spill, resulting in approximately 500,000 US gallons (1,900,000 L) of fuel oil leaking into the Savannah River.

Original design

Meaning of name "Savannah" According to Merriam-Webster's Dictionary (with etymologies), the name "Savannah" means "Shawnee"; it derives from a Muskoghean Indian word—a variant of Sawanoki, the native name of the Shawnees. Georgia colonists adopted this name for the Savannah River and then for the city. Residents of Savannah are known as Savannahians /səˈvænijənz/.

|

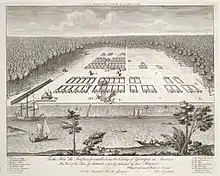

Savannah's physical layout was the subject of an elaborate plan by the Georgia colony's founders. Oglethorpe's Savannah Plan consisted of a six interconnected wards built around central squares, with trust lots on the east and west sides of the squares for public buildings and churches, and tithing lots for the colonists' private homes on the north and south sites. The wards were 675 feet on each side, excluding the surrounding streets. After Oglethorpe's return to England in 1743, the city continued to follow the general pattern established by the Oglethorpe Plan until the 1850s, when a more conventional grid was adopted.[6]

The orderly, Neo-classical design of Savannah's central city was connected to the exterior by three main roads: the Savannah-Augusta to the north, the Savannah-Dublin Road to the west and the King's Road, which connected Savannah to the provincial military settlements of Fort Argyle, Fort Barrington and Fort Frederica to the south. Spur roads were located off the King's Road as well, and connected plantations such as Wormsloe, home of Noble Jones, to the expanding and increasingly urban market in Savannah.

Economic development

Cotton industry

_pg101_OCEAN_STEAMSHIP_CO_OF_SAVANNAH%252C_PIERS_34_AND_35%252C_NORTH_RIVER.jpg.webp)

The Savannah Cotton Exchange was established in 1876 and made its permanent home on Bay Street in 1883, with the warehouses down below on River Street. The exchange was established to provide King Cotton factors, brokers serving planters' interest in the market, a place to congregate and set the market value of cotton exported to larger markets such as New York or London. By the end of the 19th century factorage was on the decline as more planters were selling their products at interior markets, thus merely shipping them from Savannah via the extensive rail connections between the city and the interior.

By 1870 three principal railroads—the Central of Georgia Railway, the Savannah and Charleston and the Savannah and Gulf—connected the city to markets along the coast and the interior. The Central of Georgia, whose principal shareholder was the city of Savannah, established its own docks and canals to the west of the existing Savannah riverfront. This marks the first shift of industrial-commercial activity outside of the central plan of the city. An additional railroad was built extending from the Drayton Street Depot out to Tybee Island in 1887. The rate, 1 cent per mile or 17.7 cents each way, enabled city dwellers to escape to the ocean and spend their newfound leisure hours at the beach on Tybee Island. This became the first commuter line from Savannah to an outlying area.

19th-century development in Savannah was dominated by the emergence of cotton as a widespread cash crop and a subsequent shift in the economy of the city. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 by Eli Whitney changed the face of agriculture in the American South. Whitney's gin was produced in response to the state of Georgia's appointed commission for the promotion of a gin suitable to remove seed from fibers on the short-staple, green-seed cotton. Whitney developed the gin at Mulberry Grove Plantation outside Savannah while he was a tutor to the children of Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene.

Sea Island or long-staple cotton had been very profitable in the years immediately following the Revolutionary War, but the production of this variety was relegated to the narrow coastal zone and would not grow in the upland interior of the South. Green-seed cotton could be grown in the uplands but was difficult to process with the pre-1793 roller gin; consequently, Whitney's invention opened the interior of the South to widespread cotton production.

The development of Georgia's interior had a tremendous impact on Savannah, as cotton production was focused on lands newly appropriated from the Creeks along the upper Savannah River. Planters on both the Georgia and South Carolina sides of the river shipped their cotton downriver to market and export at Savannah. This increase in trade corresponds to the increase in population, as Savannah was the eighteenth-largest urban area in the United States by 1820. In 1818 shipping and business stopped temporarily when the city fell under quarantine due to a yellow fever epidemic.

Economic competition This monopoly on the interior markets did not last long; in 1833, the South Carolina Railroad, extending from Charleston to Hamburg, South Carolina, was completed. The longest rail line of its day, the South Carolina Railroad was primarily built to redirect the export of cotton grown along the Savannah River through Charleston. The siphoning-off of cotton markets along the upper Savannah prompted the increased interest in the development of north Georgia. The Central of Georgia Railroad was organized in 1833 to open a commercial line between Savannah and the vast interior of central and north Georgia. The forcible expulsion of nearly 18,000 Cherokees, following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, ensured that north Georgia would be open to settlement and cotton production. The Central of Georgia Railroad extended to Macon by 1843 and to Terminus (later known as Atlanta) by 1846.

|

In 1828, construction began on the Savannah-Ogeechee Canal, a 16.5-mile (26.6 km) canal connecting the Ogeechee River to the southwest (near present-day Richmond Hill) and the Savannah River, slightly to the west of Savannah's newly established riverfront. The canal was completed in 1831, directing the resources of Georgia's south-central interior to Savannah. The expansions of Savannah during the 1830s and 1840s led to the need for a new city map, which was published by Edward A. Vincent in 1853.

Despite its small population, Savannah amassed an enormous amount of wealth. By 1820, Savannah was exporting $18 million worth of goods. It is important to recognize, however, that this wealth came about as the result of both the removal of indigenous peoples from the interior as well as the slave trade. Although originally banned from the colony upon the insistence of Oglethorpe, the slave population exceeded the free population in Savannah by the end of the 18th century (5,146 free and 8,201 slave in 1800). Little is known about the slave population of Savannah beyond what can be read in census information: between 1810 and 1830, there was a decrease in the number of slaves in the city, followed by an increase in the slave population from 9,478 in 1830 to 14,018 in 1850. As the population of free people of color grew by 68 percent between 1850 and 1860, the slave population remained relatively stable. Additionally, Savannah retained a consistent number of free African Americans throughout the antebellum years (725 in 1860), and they were engaged in a variety of entrepreneurial activities.

Heavy industry and manufacturing

Diversification in Savannah's economy arrived as heavy industry and manufacturing entered into the region during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Union Camp, a division of the American Pulp and Paper Company, was established around the turn of the 20th century, locating its mill upriver from the historic core of the city. Contributing to the trend of upriver industrial development, the Kehoe Iron Works was established in 1883 by Irish immigrant William Kehoe.

As working-class residents began to move into neighborhoods adjacent to the new industries, the population of the densely packed historic core of the city began to dissipate. Additionally, building continued to the south, as the city experienced a 65 percent increase in population between 1900 and 1920 (54,244 in 1900 to 83,252 in 1920).

An additional boost to Savannah's economy arrived with the increased export of naval stores. Items such as pitch and turpentine, recovered from South Atlantic yellow pine, were essential in the manufacture and upkeep of wooden ships. In 1902 the naval stores industry was revolutionized by former University of Georgia chemist Charles Herty. Herty devised a method of collecting the raw sap from yellow pine in nearby Statesboro, Ga., proved that the method was not only more effective than previous methods of extraction but also enabled the trees to live into maturity and be eventually harvested. The harvesting of yellow pine further diversified Savannah's economy as a lumber exporter. By this time Savannah, with vast yellow pine forests extending far into Georgia's coastal plain, became the chief exporter of naval stores in the world.

The boll weevil outbreak of the 1920s dealt a devastating blow to the cotton market of Savannah and the South in general. The naval stores industry also fell into decline by World War II as iron had largely replaced wood in the manufacture of ships. Savannah's economy continued to shift as more heavy industry was added upriver. During World War II, Savannah manufacturing aided the war effort through the construction of Liberty ships, further shifting the population out of the historic core of the city.

Development of the tourism industry

In the 1930s and 1940s, some of the distinguished buildings in the historic district were demolished, and the trend appeared to be poised to accelerate in the 1950s when city plans were drafted to make downtown Savannah competitive with commercial development in the emerging suburbs. The threat of demolition of historic structures to make way for high-rise buildings, parking, road widening, and freeways spurred concern over the city's historic legacy.[22] In 1955, the demolition of the City Market (1870) on Ellis Square and the attempted demolition of the Davenport House (1821) prompted seven Georgia women, led by Davenport descendant Lucy Barrow McIntire, to create the Historic Savannah Foundation. In the late 1950s, and throughout the 1960s, the foundation was able to halt some further destruction of historic buildings and to preserve original structures. In 1978 the Savannah College of Art and Design was founded, and rather than building one centralized campus, it began a process of renovation and adaptive reuse of many notable downtown buildings. These efforts, along with the work of the Historic Savannah Foundation and smaller preservation groups, have contributed greatly to Savannah's now-famous rebirth.

The city's popularity as a tourist destination, modest in the 1970s, grew in the 1980s and was solidified by the best-selling 1994 book and 1997 motion picture Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, both set in Savannah.

Public drinking policy Downtown Savannah's historic district is one of only five places in the United States where possession and consumption of open containers of alcoholic beverages are allowed on the street (but not in a vehicle), although they remain prohibited throughout the rest of Savannah. (Only one open plastic container is allowed per person over the age of 21, and it can be no larger than 16 ounces.)[23]

|

Savannah has also become a popular destination for people to celebrate St. Patrick's Day, including the second-largest parade in the United States. This is aided by a very lenient public drinking policy which allows open alcoholic beverages every day of the year in the Landmark Historic District.

Notes

- A.^ Savannah had six original squares laid out under Oglethorpe. The design was ultimately expanded to 24 squares by the early 1850s. Today 22 are still in existence. See Squares of Savannah, Georgia for additional information.

References

- "Savannah". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. September 11, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- "Savannah Information". Savannah Area Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- Jackson, Edwin L. (August 1, 2019). "James Oglethorpe (1696-1785)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- O.S. February 1, 1732, according to the Julian calendar used in the British colonies until September 2, 1752. With the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, eleven days in the date were omitted and the modern New Year (January 1) replaced the Julian contemporary New Year (March 25), previously observed in England and Wales. The Gregorian date in 1733 is observed locally, just as Gregorian dates are used throughout the United States for this era.

- "The Jewish Community of Savannah". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- Wilson, Thomas D. The Oglethorpe Plan: Enlightenment Design in Savannah and Beyond. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2012. Chapter 4.

- Patricia U. Bonomi, "Under the Cope of Heaven. Religion, Society and Politics in Colonial America", Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 33

- Bonomi, 1986, Chapter 7 'Religion and the American Revolution'

- Hirschfeld, Fritz (2005). George Washington and The Jews. University of Delaware Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-87413-927-3.

- "Our History". Grand Lodge of Georgia. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- "Home page of Solomon's Lodge".

- Tatsch, J. Hugo (1995). Solomon's Lodge and Freemasonry in Georgia, Freemasonry in the Thirteen Colonies. Kessinger Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-56459-595-9.

- Chappell, Joseph Harris (1905). Georgia History Stories. Chapter X: the Capture of Savanna. Silver, Burdett. pp. 131–144.

- Mason, Matthew (2008). "'The Fire-Brand of Discord': The North, the South, and the Savannah Fire of 1820". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 92 (4): 443–459. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- Lockley, Tim (2012). "'Like a clap of thunder in a clear sky': differential mortality during Savannah's yellow fever epidemic of 1854" (PDF). Social History. 37 (2): 166–186. doi:10.1080/03071022.2012.675657. S2CID 2571401.

- Public Health Papers and Reports, Volume 5. American Public Health Association. 1880. p. 89.

- Report by Maj. Gen. W.T. Sherman, January 1, 1865, quoted in Grimsley, p. 200

- History Channel

- Ebook on President Grover Cleveland's 1888 visit.

- Savannah, Georgia by Charles J. Elmore Ph.D. page 7

- "For 50 Years, Nuclear Bomb Lost in Watery Grave". NPR. February 3, 2008.

- Wilson, T., The Oglethorpe Plan, chapter 4.

- "Savannah City Code Section 6-1215(b)". Retrieved November 28, 2007.

Further reading

- Anbinder, Tyler. "Irish Origins and the Shaping of Immigrant Life in Savannah on the Eve of the Civil War," Journal of American Ethnic History 35#1 (Fall 2015), 5–37.

- Blassingame, John W. “Before the Ghetto: The Making of the Black Community in Savannah, Georgia, 1865-1880.” Journal of Social History 6#4 (1973), pp. 463–88. online

- Coffey, Tom. Savannah Lore and More. Savannah, Ga.: Frederic C. Beil, 1997.

- Russell, Preston, and Barbara Hines. Savannah, Ga.: A History of Her People Since 1733 Savannah, Ga.: Frederic C. Beil, 1992.

- Smith, Derek. Civil War Savannah Savannah, Ga.: Frederic C. Beil, 1997.

- Veasey, Ashley, "Liberty Shipyards: The Role of Savannah and Brunswick in the Allied Victory, 1941–1945," Georgia Historical Quarterly, 93 (Summer 2009), 159–81.

- Wilson, Thomas D. The Oglethorpe Plan: Enlightenment Design in Savannah and Beyond. Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press, 2012.

External links

- Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning – National Park Service Teaching Lesson

- Georgia Historical Society

- Historic Savannah Foundation

- Ebook on President Grover Cleveland's 1888 visit

- 1905 National Magazine article with historical photos

- The Journal of Peter Gordon, 1732–1735 – University of Georgia Press Digital Publishing (manifoldapp.org)