History of St. Louis (1866–1904)

The history of St. Louis, Missouri, from 1866 to 1904 was marked by rapid growth. Its population increased, making it the country's fourth-largest city after New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago.[1] It also saw rapid development of heavy industry, infrastructure, and transportation. The period culminated with the city's hosting of the 1904 World's Fair and 1904 Summer Olympics.

| History of St. Louis |

|---|

|

| Exploration and Louisiana |

| City founding and early history |

| Expansion and the Civil War |

| St. Louis as the Fourth City |

| Urban decline and renewal |

| Recent developments |

| See also |

Infrastructure and parks

During the Civil War, the infrastructure of St. Louis was neglected. Typhoid fever raged in certain quarters. Another cholera epidemic struck in 1866, killing more than 3,500 people.[2] In response, the city established the St. Louis Board of Health, which was given power to create and enforce sanitary regulations and monitor the activities of certain polluting industries.[3] To rectify some of the problems with the water system, a new waterworks was built in north St. Louis in 1871, accompanied by a large reservoir at Compton Hill and a standpipe at Grand Avenue.[4] But the system was plagued by high demand and the dumping of waste upriver from the waterworks.[4] The gas light system also saw improvements during the 1870s, when the Laclede Gaslight Company was formed to serve the south side of the city.[4]

In the early 1870s, new industries began to grow in St. Louis, such as cotton compressing, a process in which raw cotton is compressed for easier shipment.[5] By 1880, St. Louis was the third-largest raw cotton market in the United States, with an overwhelming majority of it transported to the city by railroad.[6] Among these new railroad connections was the Cotton Belt Railroad, organized in St. Louis in 1879 from smaller lines that connected the region to cotton producers in Texas.[6]

St. Louis also expanded its park system during the 1860s and 1870s.[7] Besides the common fields which were converted into Lafayette Park, in 1868 Henry Shaw donated land for Tower Grove Park. In 1872, the state legislature authorized the city to purchase more than 1,000 acres for a park.[7] After a series of court challenges, the city completed the purchase of land in a largely rural area[8] at the city's western border in 1874 and Forest Park was opened in 1876.[7][9] The editorial staff of the St. Louis Globe Democrat and others initially doubted it, the city eventually grew to surround the park.[10] The park site was among the last in St. Louis County (now in St. Louis City) to contain Native American burial mounds.[10] Although it opened as an integrated park, Jim Crow laws eventually restricted the use of the park by African-Americans.[11]

Innovation and segregation in schools

After the Civil War, school taxes increased and became largely dependent on property values.[12] By 1870, the public and parochial school systems had 24,347 and 4,362 students respectively.[12] Starting in the 1870s, St. Louis schools adopted William Torrey Harris's discipline and curriculum, which focused on rigorous obedience and training in grammar, philosophy, and mathematics.[13] Harris also embraced innovation by establishing the first public kindergarten in the United States, under the instruction of Susan Blow in 1874.[13] Despite early objections to the idea, kindergarten was particularly popular in St. Louis, serving 7,800 students by the end of the 1870s.[13]

Segregated schools for African-Americans had begun in the 1820s under the tutelage of ministers John Mason Peck and John Berry Meachum, but these schools were closed by local police.[12] Another school opened under the authority of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet in 1845, but a mob attacked the convent and closed the school.[12] Two years later, the state legislature banned education for free blacks (slave education had already been prohibited).[12] Meachum operated school aboard steamboats in the Mississippi River during the 1840s and 1850s; and local black churches also operated secret schools in basements.[12]

In 1864, an integrated group of St. Louisans formed the Board of Education for Colored Schools, which established schools without public finances for more than 1,500 pupils in 1865.[12] The Missouri Constitution of 1865 required municipalities to support black education; in response, the St. Louis Board of Education appropriated .2% of its budget for that purpose.[14] This sum amounted to $500, meaning that facilities were quite poor; long walking distances from schools were common, and teacher salaries were roughly half of those in white schools.[14] In 1875, after considerable effort and protest from the black community, high school classes began to be offered at Sumner High School, the first high school for black students west of the Mississippi.[15] However, inequality remained rampant in St. Louis schools.[15]

Railroads, the Eads Bridge and Union Station

In addition to connecting St. Louis with the west, the railroads began to demand connections with the east across the Mississippi.[6] From 1820 to 1865 a single ferry company in Illinois controlled the majority of traffic across the river, leading to high costs and delays during winter.[6] Plans for a bridge over the river had begun as early as 1839, but were abandoned due to cost.[16] After the Civil War bridges across the Mississippi were completed at Quincy, Illinois and Dubuque, Iowa, linking Chicago to western markets at the expense of St. Louis.[17] State legislators from northern Illinois conspired during the late 1860s to prevent or delay bridge construction originating in East St. Louis, Illinois, in order to cement the position of Chicago as a transit hub.[18] However, in 1867 leading St. Louis bankers and merchants formed a company to bridge the river from the Missouri side.[19]

The chief engineer for the bridge project was James B. Eads, a self-taught engineer and accomplished diver and salvage ship operator.[19] During the Civil War Eads aided the Union by designing ironclads.[19] The foot of the St. Louis bridge on the west bank was at the relatively wide Washington Avenue, giving it the advantage of allowing heavy road and rail traffic.[19] Congress had prohibited Eads from building a suspension bridge across the Mississippi due to multiple recent failures, and a truss bridge favored by many bridge builders at the time would require at least five separate spans.[20] Thus, Eads and his German assistants, Henry Flad and Charles Pfeifer, settled on an arch bridge design with three spans.[21]

Excavations for the bridge piers began in September 1867 and continued through 1871, using the relatively new pneumatic caisson technique.[22] However, the effects of pneumatic caissons were poorly understood, leading to the deaths of 14 workers due to caisson disease, also known as the bends.[23] In March 1870 a doctor was engaged to assist; he recommended a decompression schedule that reduced the problems.[23] In 1871 work began on the superstructure of the bridge, and the upper roadway was completed in April 1874.[24]

On May 24, 1874, a large crowd of St. Louisans were permitted on the roadway deck, and in June the bridge's weight limits were tested using a coal wagon, a train, and an elephant.[25] On July 2, 1874, fourteen locomotives loaded with coal pulled onto each span, putting to rest concerns about the bridge's safety.[25] Two days later, as part of the city's Independence Day celebrations, the bridge opened with a parade and a crowd in excess of 200,000.[25] Costs for the bridge exceeded estimates, reaching $6.5 million for labor, land, and supplies, which increased to $9 million when including bond interest.[26] A 5,000-foot tunnel connecting the bridge with the St. Louis railroad yards and costs to modify streets were approximately $2 million.[26]

To accommodate increased rail traffic, a new railroad terminal, Union Depot, was constructed in 1875, but it was not large enough to consolidate all train service in one location.[26] Due to the Panic of 1873, the terminal, the company owning the Eads Bridge, and the company owning the St. Louis tunnel were purchased by Jay Gould in 1886 for $3.5 million.[27] In 1889, Gould formed the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis (TRRA), which took over operations of the bridge and the train station, and in 1893, the TRRA purchased the Merchants Bridge, a railroad-only bridge built in 1889.[27] The TRRA then began to plan for a new railroad station in St. Louis, which would replace the 1875 structure and consolidate all St. Louis railroad activity.[27]

The TRRA invited ten architects to submit designs for the station with general requirements as to the size of the building.[28] The design by Theodore Link was approved in July 1891.[29] Construction costs were $6.5 million, and Union Station formally opened on September 1, 1894.[30] Although Chicago, Illinois had a greater volume of traffic at its Union Station, more railroads met at St. Louis than any other city in the United States.[31] Union Station's rail platform expanded in 1930 and operated as the passenger rail terminal for St. Louis into the 1970s.[31]

The development of interurban rail was marked by the 1899 consolidation of 10 independent streetcar lines into two. One of those two, the St. Louis Transit Company, was the target of the St. Louis Streetcar Strike over the summer months of 1900, a strike that developed into a civil disruption, leaving 14 dead and hundreds injured.

Separation from St. Louis County

When Missouri became a state in 1821, St. Louis County was created from the boundaries of the former St. Louis subdistrict of the Missouri Territory; St. Louis city existed within the county but was not coterminous with it. Starting in the 1850s, rural county voters began to exert political influence over questions of taxation in the St. Louis County court.[31] In 1867, the county court was given power to assess and collect property tax revenue from St. Louis city property, providing a financial boon to the county government while depriving city government of revenues.[32] After this power transfer, St. Louisans in the city began to favor one of three options: greater representation on the county court via charter changes, city-county consolidation, or urban secession to form an independent city.[32]

Early efforts focused on the first option, which was to revise the county charters to force greater representation of city interests on the county court.[32] In spite of efforts by state representatives from the city (including a young Joseph Pulitzer), county lobbyists persuaded the General Assembly to deny changes to the county charter.[32] In 1873, the Democratic Party regained political control in Missouri for the first time after the Civil War, prompting the rewriting of the Missouri Constitution in 1875.[33] At the convention, St. Louis area delegates took up the question of how to solve the region's city-county disputes.[34] The delegates ruled out consolidation as too impractical and expensive from a management perspective; separation was considered the primary goal.[34]

The negotiations on how to proceed among the St. Louis delegates stalled, however, until the arrival of David H. Armstrong, a well-respected politician.[34] Armstrong created consensus among the St. Louisans, then persuaded the full convention to support the proposal.[35] The proposal of the delegates, to separate the city from the county, was regarded as a local reform effort to eliminate government corruption.[36] The full constitutional convention approved the proposal, and the new Missouri Constitution was narrowly approved by voters in November 1874.[37]

The proposal and constitution created a Board of Freeholders from among St. Louis city and county, tasked with reorganizing them into two separate political entities.[35] In a series of meetings in the summer of 1876, the Board of Freeholders determined that the city would "perform all functions in relation to the state as if it were a county ..." and established the provisions of the city charter, including the creation of 28 wards and four-year mayoral terms.[38] The new city charter also tripled the size of the city to include the new rural parks (such as Forest Park) and the useful riverfront from the Missouri-Mississippi confluence to the mouth of the River Des Peres.[39] The Board announced its plans on July 4, 1876.[39] Upon approval of the plan by city and county voters, the city would become the County of the City of St. Louis, assume all county debt, and purchase the Old Courthouse.[40] The county would remain the County of St. Louis but would lose access to tax revenue from city property.[40]

On August 22, 1876, St. Louis voters initially appeared to have rejected the separation plan by a vote of 14,132 to 12,726.[40] The vote, however, was fraudulent; in one voting precinct, 128 of 132 "no" votes showed evidence of having been erased "yes" votes.[40] Other precincts had more votes than voters, while poll workers testified to being ordered to stuff ballot boxes with "no" votes.[41] A recount commission investigated the fraud and subsequently altered the vote totals, and in December 1876 the separation was approved.[41]

Industrialization

"The City of St. Louis has affected me more deeply than any other environment has ever done, I consider myself fortunate to have been born here, rather than in Boston, or New York, or London."

T. S. Eliot on St. Louis

In 1880, the leading industries of St. Louis included brewing, flour milling, slaughtering, machining, and tobacco processing.[42] Other industries including the making of paint, bricks, bags, and iron.[42] During the 1880s, the city grew in population by 29 percent, from 350,518 to 451,770, making it the country's fourth largest city; it also was fourth measured by value of its manufactured products, and more than 6,148 factories existed in 1890.[43] However, during the 1890s manufacturing growth slowed dramatically.[43] The Panic of 1893 and subsequent depression and the overproduction of grain made St. Louis mills considerably less productive and valuable.[44] Flour milling was halved in production, and most other industries suffered declines.[44]

The brewing industry, which originated in St. Louis in the years after the Louisiana Purchase, was limited in scope to local production during the pre-Civil War era.[45] The arrival of Adam Lemp in 1842 changed much of the beer industry in the area; Lemp introduced lager beer, which quickly became the most popular type of beer in St. Louis.[46] The industry also expanded rapidly in the late 1850s, from 24 breweries in 1854 to 40 in 1860.[46] Brewing became the city's largest industry by 1880, but dropped from the nation's second-largest beer producer in 1890 to fifth in 1900.[44]

However, reported revenue of brewers in St. Louis suggests that the 1900 figure (derived from the U.S. Census) was low.[47] The two largest St. Louis brewers, Anheuser-Busch (the world's largest brewery) and Lemp Brewery, together produced 1.5 million barrels in 1900.[47] St. Louis breweries also were innovators: Anheuser-Busch pioneered refrigerated railroad cars for beer transport and was the first company to market pasteurized bottled beer.[48]

Pollution

Among the downsides to rapid industrialization was pollution, of which St. Louis generated a great deal.[42] Brick firing produced particulate air pollution and paint making created lead dust, while beer and liquor brewing produced grain swill.[42] However, the worst pollution was coal dust and smoke, for which St. Louis was infamous by the 1890s.[42] Nearly every factory relied on coal to fire steam boilers, the region's homes used a relatively more polluting form of bituminous coal, and railroad traffic created large, dense clouds of coal smoke around depots and railyards.[42] Noise pollution also was a problem, as many residential areas were intermixed with industrial areas.[42] In spite of efforts to fill sinkholes before the Civil War, quarries dug holes in lots to produce brick, stone and soil for the building trades.[49] These holes often filled with industrial waste, sewage, garbage, and dirty runoff.[49]

The greatest complaints to the St. Louis Board of Health, however, were due to the presence of industries engaged in rendering, a process in which decaying animal carcasses were converted into useful products.[50] Generally, after an animal was slaughtered for meat consumption, hides were sent to be cured and tanned, while the remaining fat and bones were sent to renderers.[50] Most rendering factories produced particularly noxious fumes, often regarded as health hazards.[51] Smells from the factories and offal sent to them were reportedly "so putrid that a wagon loaded with [spoiled offal] can be smelled for miles ... and while rendering the fetid smell sickens inhabitants for miles around."[52] The stench of bone rendering factories was said to have been so thick and bad that it "slowed the incoming trains."[53]

In spite of this, courts and legal mechanisms to end pollution were hindered by a desire to promote economic growth; if a complaint was substantiated (difficult in itself), the judgment often did not end the offending pollution but merely required damage payments.[3] One of the few health policies to be carried out began in 1880; in the new policy, nuisance regulations would be enforced strictly in some areas while little in others, thereby encouraging offending industries to concentrate in certain areas.[54] The Board of Health generally avoided concentrating industries in areas with higher property values, and in general attempted to force manufacturers to the North Riverfront and Baden neighborhoods.[55] Other industries congregated along the Pacific Railroad line through Mill Creek Valley, an area later declared blighted and demolished in the 1940s.[56]

Commercial and residential growth

St. Louis is one of several cities that claims to have the world's first skyscraper. The Wainwright Building, a 10-story structure designed by Louis Sullivan and built in 1892, still stands at Chestnut and Seventh Streets, and is today used by the state of Missouri as a government office building. Corporations such as Ralston-Purina (headed by the Danforth family), the Brown Shoe Company, and the Desloge Consolidated Lead Company (headed by the Desloge family) were either headquartered or founded in St. Louis.

From the early 1840s, the wealthiest families of St. Louis often resided in enclaves on the outskirts of the city.[57] In the 1850s and 1860s, many wealthy businessmen lived along Washington Avenue, but the construction of the Eads Bridge encouraged commercial development in the area.[58] Other well-to-do areas included Lucas Place and Lafayette Square, which were developed in the 1850s and peaked in popularity in the 1870s.[58] Of Lucas Place, only the Campbell House remains extant after falling from popularity when the city divided a nearby park and connected the private street to the common grid.[59] Lafayette Square remained popular until the 1896 St. Louis-East St. Louis tornado, which killed more than 140 and destroyed dozens of buildings on the square.[60] Although some homes were rebuilt, many residents moved from the area, and by 1918 the area surrounding Lafayette Square was rezoned for commercial use.[60]

After Lafayette Square, wealthy St. Louisans moved during the 1890s to a private place in Midtown, St. Louis known as Vandeventer Place, but due to the expansion of the streetcar system, nearby streets had commercialized by 1910.[61] This commercialization led the wealthy to move farther west, to the Central West End neighborhood, which included the private places of Westmoreland Place, Portland Place, and Washington Terrace.[62] The owners of these residences formed an elite ruling class known locally as the "Big Cinch", including St. Louis Mayor Rolla Wells, Missouri Governor David R. Francis, and United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor Charles Nagel.[62]

The development of private places in the Central West End during the 1890s coincided with the rise of country estates in St. Louis County.[63] The rural towns of Normandy, Wellston, and Florissant were connected to St. Louis by railroad starting in 1876, allowing for the development of large estates in those areas.[63] It also encouraged the construction of social clubs and golf courses such as the Glen Echo Country Club and the Normandie Golf Club (the first and second golf courses west of the Mississippi, respectively).[61] Poets Sara Teasdale and T. S. Eliot as well as playwright Tennessee Williams called the city home during this period.

Nikola Tesla conducted a public demonstration of his wireless lighting and power transmission system here in 1893. Addressing the National Electric Light Association, he showed "wireless lighting" [64] in 1893[65] via lighting Geissler tubes wirelessly. Tesla proposed this wireless technology could incorporate a system for the telecommunication of information.

Music and sports in St. Louis

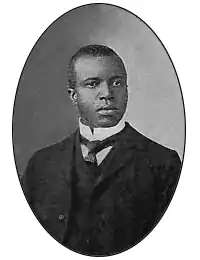

Starting in the 1890s, the district known as Chestnut Valley (an area now occupied by the Scottrade Center) became the home of St. Louis ragtime.[66] Businesses in Chestnut Valley included saloons and brothels, both of which hired musicians to play background music.[67] Among these musicians were W.C. Handy, who was stuck in St. Louis for some months in the early 1890s, a stay commemorated in his 1914 song St. Louis Blues.[68] In addition, the area was immortalized in the ragtime song Frankie and Johnny, which describes an 1899 murder that took place in Chestnut Valley.[67] Slightly west of Chestnut Valley, ragtime composer Tom Turpin operated a club and sponsored ragtime playing contests starting in the mid-1890s.[67] Several well-known ragtime artists played at Turpin's club, including Scott Hayden, Arthur Marshall, Joe Jordan, and Louis Chauvin.[67]

In addition to the early Chestnut Valley players, ragtime composer Scott Joplin moved to St. Louis from Sedalia, Missouri in 1901, where he associated with Tom Turpin and composed music in the city until moving to Chicago in 1907.[69] After 1906, several music clubs moved to an area known as Deep Morgan, located on Biddle Street in north St. Louis. Blues and Boogie Woogie pianists like Henry Brown [70] played regularly in the Deep Morgan area (Among other blues numbers he recorded Deep Morgan Blues). [71] In Deep Morgan, ragtime evolved into blues, while clubs that remained in Chestnut Valley began playing early jazz music.[68] Early jazz musicians such as Pee Wee Russell played in Chestnut Valley, while vaudeville theaters in the area featured acts such as Eva Taylor.[72]

The home Joplin rented in 1900-1903 was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1976 and was saved from destruction by the local African American community. In 1983, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources made it the first state historic site in Missouri dedicated to the African American heritage. At first it focused entirely on Joplin and ragtime music, ignoring the urban milieu which shaped his musical compositions. A newer heritage project has expanded coverage to include the more complex social history of black urban migration and the transformation of a multi-ethnic neighborhood to the contemporary community. Part of this diverse narrative now includes coverage of uncomfortable topics of racial oppression, poverty, sanitation, prostitution, and sexually transmitted diseases.[73]

The sport of baseball began to be played in St. Louis in the years following the Civil War; a team known as the St. Louis Brown Stockings was founded in the city in 1875.[74] The Brown Stockings were a founding member of the National League and became a hometown favorite, defeating the Chicago White Stockings (later the Chicago Cubs) in their opener on May 6, 1875.[75] However, the original Brown Stockings club closed in 1878, and an unrelated National League team with the same name was founded in 1882.[74] This team changed its name multiple times, shortening to the Browns in 1883, then becoming the Perfectos in 1899, and settling on the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900.[74]

During the 1880s, St. Louis also was home to another club, the St. Louis Maroons, which relocated to Indianapolis in 1887. In 1901, St. Louis became a two-team city again with the addition of an American League team, the St. Louis Browns.[76] The Browns were more popular than the Cardinals during the 1910s and 1920s, but neither won a pennant race through 1925.[76]

Corruption and Civil Unrest

In 1871, an old army buddy of Ulysses Grant by the name of John McDonald arrived in St. Louis. He was a superintendent for the Bureau of Revenue, sent to St. Louis to collect liquor taxes from distillers and distributors, primarily of whiskey. He began a wide-ranging conspiracy predicated on under-reporting whiskey production and using the difference to enrich themselves and moreover to fund Republican party political campaigns, including Grant's 1872 re-election campaign. The Whiskey Ring eventually spread to other cities, including Chicago, Milwaukee, and New Orleans. The ring expanded to include numerous Federal officials both in and outside of the Treasury department.

Following the appointment of a new Secretary of the Treasury in 1874, an investigation was begun using officials who were not affiliated with the Treasury Department. When all was said and done, 32 distilleries and bottling plants in the Midwest were seized, $3M in taxes were recovered, and 238 people were indicted. One of the individuals implicated in the conspiracy was Orville Babcock, President Grant's personal secretary and close friend. When Babcock was acquitted at trial in February 1876, it further tarnished the image of the Republican party and President Grant in particular.

St. Louis then hosted the 12th Democratic National Convention in June 1876. In response to the corruption of the Republican party, the Democratic Party nominated Samuel Tilden, Governor of New York and political reformer, for President. This contributed to the contested Presidential Election of 1876, followed by the Compromise of 1877 and the end of Reconstruction.

Frustration with one-party governance continued, and was exacerbated by a series of bankruptcies and pay-cuts by large railroad companies throughout the country. Following the third pay-cut in a year by the B&O railroad, railroad workers in West Virginia went on strike. This led to the Great Upheaval, when railroad workers across the nation went on strike against corruption, cronyism, and unjust working conditions. In some cities, like St. Louis, the strike expanded into a general strike, as workers across industries articulated demands for improved labor conditions, including an eight-hour workday and an end to child labor.

When the elected sheriff refused to suppress the strike, the elites of St. Louis pooled $20,000 to finance the hiring of 5000 "deputized special police." These special police, along with 3000 members of the National Guard sent by the Governor and at least two cannons, sacked the Relay Depot, Schuler's Hall, and other operational centers of the strike, killing eighteen, arresting scores, and putting an end to the uprising. Four days later, the special police went on a triumphant march through the city. In the wake of the arrests, the city prosecutors largely refused to prosecute the prisoners.

In response to the Great Upheaval, a group of St. Louis businessmen and former Confederates—including Alonzo W. Slayback and John Priest, the chief of police—organized the creation of the Veiled Prophet Society in 1878. Drawing on influences including New Orleans Mardi Gras krewes and Ku Klux Klan iconography, the Veiled Prophet Society undertook an annual parade and masqued ball to assert the cultural superiority of white Protestant America over Catholics, blacks, and other races, as well as associated vices such as intemperance, sloth, and lust. The parades portrayed the United States as the logical and proper end to history, and yet until 1899, did not reference the Civil War.

By 1881, 35 militias were organized throughout the city, financed by private donations and federal money earmarked for the National Guard. These militias were paramilitary outfits, staffed by volunteers who did not report to the police or the sheriff. This exempted them from public oversight. These militias were organized to suppress further workers' strikes, most notably with the Streetcar Strike of 1900. John H. Cavender—who had played a key role in the suppression of the strike in 1877—was appointed by the Police Board to organize a posse comitatus and once again put down the strike.

It is asserted that the police organized an annual parade for the next twenty years where they displayed the weapons used to murder the protesters.[77]

1904 World's Fair

Since the 1850s, St. Louis had hosted annual agricultural and mechanical fairs at Fairground Park to connect with regional manufacturers and growers.[78] However, by the 1880s, the connection to agriculture had declined, and in 1883, a new exposition hall was built at Thirteenth and Olive streets to house industrial exhibits.[78] In 1890, St. Louis attempted to host the World's Columbian Exposition, but the fair was awarded to Chicago, which hosted the exposition in 1893.[78] In 1899, delegates from states that had been part of the Louisiana Purchase met in St. Louis, selecting it as the site of a world's fair celebrating the centennial of the purchase.[79] By the end of 1900, St. Louisans had purchased more than $5 million in stock in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, and the next year, the city of St. Louis issued a bond for another $5 million for the company while the U.S. Congress appropriated the same amount.[79]

Company directors selected the western half of Forest Park as the site of the fair, sparking a real estate boom in the area.[80] To meet anticipated demand by visitors, several hotels were constructed in downtown and the Central West End, and temporary lodging was erected in the fairgrounds itself by E.M. Statler (who used profits from the facility to found Statler Hotels).[81] While the fair was under construction, it became clear that the western half of the park would not suffice for the size of the fair, so company directors leased the campus of Washington University in St. Louis and several other parcels of land, bringing the total fairgrounds to an area of 1,272 acres.[81] Streetcar and rail service to the area was improved, and a new filtration system was implemented to improve the clarity of the St. Louis water supply.[82] Other infrastructure improvements made for the fair included a wooden bridge at Kingshighway crossing the rail yards of Mill Creek Valley, and a street paving program that improved air quality by reducing airborne dust particulates.[83]

The fair itself consisted of an "Ivory City" of twelve temporary exhibition palaces, and one permanent exhibit palace which became the St. Louis Art Museum[83] after the fair. While in operation, the fair celebrated American expansionism and world cultures with exhibits of historical French fur-trading, and Eskimo and Filipino villages.[84] Concurrently, the 1904 Summer Olympics were held in St. Louis, at what would become the campus of Washington University in St. Louis.[1] Historical artifacts relating to St. Louis history were collected and exhibited by the Missouri Historical Society.[1]

Notes

- Arenson (2011), 218.

- Primm (1998), 266.

- Hurley (1997), 152.

- Primm (1998), 267.

- Primm (1998), 277.

- Primm (1998), 278.

- Primm (1998), 306.

- Arenson (2011), 205.

- Arenson (2011), 199.

- Arenson (2011), 206.

- Arenson (2011), 207.

- Primm (1998), 317.

- Primm (1998), 324.

- Primm (1998), 318.

- Primm (1998), 319.

- Primm (1998), 279.

- Primm (1998), 280.

- Primm (1998), 281.

- Primm (1998), 282.

- Primm (1998), 283.

- Primm (1998), 284.

- Primm (1998), 286.

- Primm (1998), 287.

- Primm (1998), 288.

- Primm (1998), 289.

- Primm (1998), 291.

- Primm (1998), 294.

- TRRA (1895), 17.

- TRRA (1895), 21.

- Primm (1998), 295.

- Primm (1998), 297.

- Primm (1998), 299.

- Primm (1998), 300.

- Primm (1998), 303.

- Primm (1998), 304.

- Arenson (2011), 200.

- Arenson (2011), 201.

- Primm (1998), 305.

- Arenson (2011), 210.

- Arenson (2011), 211.

- Arenson (2011), 212.

- Hurley (1997), 148.

- Primm (1998), 327.

- Primm (1998), 328.

- Primm (1998), 195.

- Primm (1998), 196.

- Primm (1998), 329.

- Primm (1998), 330.

- Hurley (1997), 149.

- Hurley (1997), 150.

- Hurley (1997), 151.

- Quoted from x in Hurley (1997), 151.

- Quoted from y in Hurley (1997), 151.

- Hurley (1997), 156.

- Hurley (1997), 158.

- Hurley (1997), 157.

- Primm (1998), 340.

- Primm (1998), 341.

- Primm (1998), 342.

- Primm (1998), 343.

- Primm (1998), 345.

- Primm (1998), 346.

- Primm (1998), 344.

- Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-691-05776-7.

- note: at St. Louis, Missouri, Tesla public demonstration called, "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena", (Journal of the Franklin Institute, Volume 136 By Persifor Frazer, Franklin Institute (Philadelphia, Pa)

- Owsley (2006), 1.

- Owsley (2006), 2.

- Owsley (2006), 7.

- Owsley (2006), 6.

- "A left Hand Like God" by Peter J. Silvester

- Owsley (2006), 5.

- Owsley (2006), 8.

- Timothy Baumann, et al. "Interpreting Uncomfortable History at the Scott Joplin House State Historic Site in St. Louis, Missouri." The public historian 33.2 (2011): 37-66. online

- Feldmann (2009), 8.

- Primm (1998), 424.

- Primm (1998), 425.

- Spencer (2000), 77.

- Primm (1998), 372.

- Primm (1998), 375.

- Primm (1998), 376.

- Primm (1998), 377.

- Primm (1998), 379.

- Primm (1998), 382.

- Arenson (2011), 217.

References

- Primm, James Neal (1998). Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri, 1764–1980. Missouri History Museum Press. ISBN 978-1-883982-25-6.

- Spencer, Thomas (2000). The St. Louis Veiled Prophet Celebration: Power on Parade, 1877-1995. University of Missouri. ISBN 9780826212672.

Further reading

- Guide book and complete pocket map of St. Louis, St. Louis: Printed by Clayton & Babington, 1867, OL 24157645M

- L. U. Reavis (1874). Saint Louis, the Commercial Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley. Tribune Publishing Company.

- "St. Louis", Appleton's Illustrated Hand-Book of American Cities, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1876

- Pictorial guide to St. Louis, St. Louis: C. N. Dry, 1877, OL 24363968M

- Police guide and directory of St. Louis, St. Louis, Mo., 1884, OL 24157692M

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Commercial and architectural St. Louis. Dumont Jones. 1891.

- Notable St. Louisans in 1900: a portrait gallery, St. Louis: Benesch, 1900, OL 7219321M

- Gould's handy guide to St. Louis, Mo., St. Louis: Acme, 1894, OL 23421862M

- "Central Continental Metropolis", Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, vol. 43, pp. 57 volumes, 1897, hdl:2027/inu.32000000494411

- William Hyde and Howard Louis Conard, ed. (1899). Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis. v.3, v.4

- Robert C. Brooks (1901), "St. Louis", Bibliography of Municipal Problems and City Conditions, Municipal Affairs, vol. 5 (2nd ed.), New York: Reform Club, OCLC 1855351

- Lincoln Steffens (1904), "(St. Louis)", The Shame of the Cities, New York: McClure, Phillips