History of Szczecin

The History of Szczecin (German: Stettin) dates back to the 8th century. Throughout its history the city has been part of Poland, Denmark, Sweden and Germany. Since the Middle Ages, it is one of the largest and oldest cities in the historic region of Pomerania, and today, is it the largest city in northwestern Poland.

Prehistory

Tacitus located the East Germanic tribe of the Rugians in the area around Szczecin, as did modern historians. The Rugians left during the Great Migrations in the 5th century AD.

Slavonic stronghold, medieval Poland (8th–12th century)

Another stronghold was built in the 8th century-first half of the 9th century at the ford of the Oder River, (at the same location where later was a ducal castle) and a few craftsmen, fishermen and traders settled in the vicinity. Later it became the main centre of a Western Slavic tribe of Ukrani (Wkrzanie) living in the fork of the Oder between the main branch and the Randow River. Several Triglav temples existed nearby.[1] Szczecin became part of the emerging Polish state under its first historic ruler Mieszko I of Poland in 967, part of which it remained for several decades.

After the decline of Wolin in the 12th century, Stetinum became one of the most important and powerful cities of the Baltic Sea south coasts, having some 5,000 inhabitants. In a winter campaign of 1121–1122, the area was subjugated by Boleslaw III of Poland, who invited the Catholic bishop Otto of Bamberg to baptize the citizens (1124). Wartislaw I, Duke of Pomerania is recorded as the local duke during this time. Wartislaw managed to expand his duchy westward, thereby forming the territorial body of the later Duchy of Pomerania, and organized the second visit of Otto in 1128. At this time the first Christian church of St. Peter and Paul was erected. It remained under Polish suzerainty until the fragmentation of Poland following the death of Boleslaw III of Poland and afterwards remained the capital of the separate Duchy of Pomerania, still ruled by the local Slavic Griffin dynasty, of which Wartislaw I was the first historical ancestor, for the centuries to come, until its extincion in 1637. Szczecin did not lose its capital status even during the partitions of Pomerania and always was seat of Pomeranian dukes.

From the late 12th century the city briefly fell under the overlordship of Saxony from 1164, Denmark from 1173, Holy Roman Empire from 1181 and again Denmark from 1185,[2] however, local dukes still maintained very close ties with the fragmented Polish realm, and Władysław III Spindleshanks (future Polish monarch) stayed at the court of Bogusław I, Duke of Pomerania in Szczecin in 1186, on behalf of his father, Duke of Greater Poland Mieszko III the Old, who also periodically was the High Duke of Poland.[3] The ducal mint in Szczecin was founded around 1185.

Capital of the Duchy of Pomerania (12th century–1630)

Duchy of Poland 967–ca. 1008

Duchy of Pomerania 1121–1647

Vassal of Poland 1121/1122–1138

Vassal of Saxony 1164–1173

Vassal of Denmark 1173–1181

Vassal of the Holy Roman Empire 1181–1185

Vassal of Denmark 1185–1235

Vassal of the Holy Roman Empire 1235–1637

Swedish Empire 1648–1720

Kingdom of Prussia 1720–1806

French occupation 1806–1813

Kingdom of Prussia 1813–1871

German Empire 1871–1918

Weimar Republic 1918–1933

Nazi Germany 1933–1945

Soviet occupation 1945

Poland 1945–present

Szczecin was held by Denmark until 1235, when it fell under the suzerainty of the multi-ethnic Holy Roman Empire.[4] In the second half of the 12th century, a group of German tradesmen (from various parts of the Holy Roman Empire) settled in the city around St. Jacob's Church, which was founded by Beringer, a trader from Bamberg, and consecrated in 1187. For centuries the dukes invited German settlers to colonize their land and to found towns and villages (see Ostsiedlung). Duke Barnim of Pomerania granted a local government charter to a local community in 1237, separating the Germans from the Slavic majority community settled around the St. Nicholas Church (in the neighborhoods of Chyzin, Uber-Wiken, and Unter-Wiken). Barnim granted the city Magdeburg rights in 1243. In 1277 the city purchased the nearby villages, present-day districts, Krzekowo and Osów.[5] In 1278 Szczecin, along with several other cities, was exempted by King Eric V of Denmark from customs duties for a fair organized in Zealand, Denmark.[5] This is the first case of the city's connections with the Hanseatic League.[5] Around that time the major ethnic group of the city had become German, while the Slavic population decreased.

In 1273 in Szczecin duke of Poznań and future King of Poland Przemysł II married princess Ludgarda, granddaughter of Barnim I, Duke of Pomerania, in order to strengthen the alliance between the two rulers.[6]

From 1295 to 1464 the city was the capital of a splinter Pomeranian realm known as the Pomerania-Stettin. (Its Dukes were Otto I, Barnim III the Great, Casimir III, Swantibor I, Boguslaw VII, Otto II, Casimir V, Joachim I the Younger, Otto III.) In 1478 it became part (and capital) of the reunited Duchy of Pomerania under duke Bogislaw X, and in 1532 it again became the capital of a splinter eponymous duchy.[7]

In the 13th and 14th centuries the town became the main Pomeranian centre of trade in grains, salt and herrings, receiving various trading privileges from their dukes (known as emporium rights). It was granted special rights and trading posts in Denmark, and belonged to the Hanseatic trading cities union. In 1390 trade privileges were granted to Stettin by the Polish king Władysław II Jagiełło who established new trade routes from Poland to the Pomeranian ports. In the 14th and 15th centuries, Stettin conducted several trade wars with the neighboring cities of Gartz, Greifenberg (Gryfino) and Stargard over a monopoly on grains export. The grain supplying area was not only Pomerania but also Brandenburg and Greater Poland – trade routes along the Oder and Warta rivers. The 16th century saw the decline of the city's trading position because of the competition of the nobility, as well as church institutions in the grains exports, a customs war with Frankfurt (Oder), and the fall of the herring market. Social and religious riots marked the introduction of the Protestant Reformation in 1534.

Around 1532 minting of coins in the city was halted, to be resumed in 1580 under duke John Frederick.[7] Then were minted the first thalers of the Duchy of Pomerania.[7]

In 1570, the Northern Seven Years' War between Denmark and Sweden was ended in the city by the Treaty of Stettin (1570).

From 1606 to 1618 the city was the residence of Duke Philip II, the greatest patron of the arts among all Pomeranian dukes.[7] He founded a rich collection of ancient and early modern coins at the Ducal Castle.[7] In 1625 the city became again capital of the reunited Duchy of Pomerania under Boguslaw XIV.[7]

By the 1630s the city and surrounding area that hadn't been already German had become completely Germanized.

Under Swedish rule (1630–1720)

During the Thirty Years' War, Stettin refused to accept German imperial armies, instead the Pomeranian dukes allied with Sweden. After the Treaty of Stettin (1630) manifested Swedish occupation, Stettin was fortified by the Swedish Empire. After the death of the last Pomeranian duke, Boguslaw XIV, Stettin was awarded to Sweden with the western part of the duchy in the Peace of Westphalia (1648), but remained part of the Holy Roman Empire. The Swedish-Brandenburgian border was settled in the Treaty of Stettin (1653). The King of Sweden became Duke of Pomerania and as such held a seat in the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire. The city was cut off from its main trading area, and was besieged in several wars with Brandenburg which shattered the city's economy, which fell in prolonged economic decline.

In 1654 the last Pomeranian duke Boguslaw XIV was buried in the Ducal Castle.

Major Prussian and German port (1720–1918)

In 1713, Stettin was occupied by the Kingdom of Prussia; the Prussian Army entered the city as neutrals to watch the ceasefire and refused to leave. In 1720 the city was officially awarded by Sweden to Prussia. In the following years Stettin became the capital of the Prussian Province of Pomerania, and the main port of the Prussian state. From 1740 onwards, the Oder waterway to the Baltic Sea and the new Pomeranian port of Swinemünde (Świnoujście) were constructed.

In 1721, a French commune was founded in the city for the Huguenots.[8] The French were subject to separate French law and had a separate French court, which existed until 1809.[8] In the following years, large groups of Huguenots settled in the city, bringing new developments into the city crafts and factories. The French greatly contributed to the city's economic revival, and were treated with reluctance by the German burghers and city authorities.[9] The population increased from 6000 in 1720 to 21,000 in 1816, and 58,000 in 1861.

During the Napoleonic Wars, in 1806 the city surrendered to France without resistance,[10][11][12] and in 1809 also Polish troops were stationed in the city. In 1813 the city was besieged by combined Prussian-Russian-Swedish forces, and the French retreated in December 1813.[13] Afterwards it fell back to Prussia.

The 19th century was an age of large territorial expansion for the city, especially after 1873, when the old fortress was abolished. In 1821, the crafts corporations were abolished, and in steam transport on the Oder began, allowing further development of trade. The port was developing quickly, specialising in exports of agricultural products and coal from the Province of Silesia. Economic development and rapid population growth brought many ethnic Poles from Pomerania and Greater Poland looking for new career opportunities in the Stettin industry. More than 95% of the population consisted of Germans. In 1843, Stettin was connected by the first railway line to the Prussian capital Berlin, and in 1848 by the second railway to Posen (Poznań). New branches of industry were developed, including shipbuilding (at the AG Vulcan Stettin and Oderwerke shipyards) and ironworks using Swedish ores. Before World War I, there were 3,000 Polish inhabitants in the city,[14] including some wealthy industrialists and merchants. Among them was Kazimierz Pruszak, director of the Goleniów (then Gollnow) industrial works, who predicted eventual "return of Szczecin to Poland".[14] The population grew to 236,000 in 1910 and 382,000 in 1939.

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), the Prussians established a prisoner-of-war camp for around 1,700 French troops in the city, of which 600 died.[15] There is a memorial at the site of the former cemetery of the French POWs.[15]

Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany (1918-1945)

In 1918, the city became part of the new Free State of Prussia, part of the Weimar Republic.

After World War I, the economy of Stettin declined again because the seaport was separated from its agricultural supply areas in Posen with the creation of the Second Polish Republic.

In the deeply flawed[16] March 1933 German federal election the Nazi Party received 79,729 votes in the city, i.e. nearly half of the votes cast. The socialists, communists and conservative nationalists have also received noticeable support, receiving 22%, 13% and 11.4% of the votes respectively.[12]

During World War II, the Germans operated over 100 forced labour camps in the city, including multiple Polenlager camps solely for Poles,[17] a Nazi prison with forced labour subcamps in the region,[18] and a Dulag transit camp for prisoners of war.[19] The city was a major centre of weapons industry (including the car production Stoewer). The Polish resistance movement was active in the city and conducted espionage of the Kriegsmarine, infiltrated the local German industry, distributed underground Polish press,[20] and facilitated escapes of Polish and British prisoners of war who fled from German POW camps via the city's port to neutral Sweden.[21] 65% of the city's buildings and almost all of the city centre, seaport, and industry were destroyed during the Allied air raids in 1944, and heavy fighting between the German and Soviet armies (26 April 1945).

Polish diaspora

In the interwar period Polish presence fell to 2,000 people.[14] Between 1925 and 1939 a Polish Consulate existed, which initiated the foundation of a Polish school, where Polish was taught, and a scouts team.[22] The Polish minority remained active despite repressions,[14][23] a number of Poles were members of the Union of Poles in Germany.[14]

Repressions against Poles intensified especially after Adolf Hitler came to power led to closing of the school.[14] Members of Polish community who took part in cultural and political activities were persecuted and even murdered (see Nazi crimes against the Polish nation). In 1938 the head of Stettin's Union of Poles unit Stanisław Borkowski was imprisoned in the Oranienburg concentration camp.[14] In 1939 all Polish organisations in Stettin were disbanded by German authorities. During the war, some teachers from the Golisz and Omieczyński schools were executed.[14]

According to German historian Jan Musekamp, the activities of the Polish pre-war organizations were exaggerated after World War II for propaganda purposes.[24]

Polish People's Republic

After World War II, the Polish-German border was preliminarily moved by the Allies to the west of the Oder-Neisse line, which would have made Stettin remain German. On 28 April 1945 Piotr Zaremba, nominated by Polish authorities as mayor of Szczecin came to the city. In early May the Soviet authorities appointed the German Communists Erich Spiegel and Erich Wiesner as mayors.[25] and forced Zaremba to leave the city twice[26] According to Zaremba initially about 6,500 Germans remained in the city.[27] Polish authors estimate the number of Poles in the city at this time at 200.[28] The German population returned, as the war was over. It was undecided if the city would be in Poland or in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, but eventually Szczecin was handed over to Polish authorities on 5 July 1945 -as agreed by the Soviet-imposed Treaty of Schwerin of 21 September 1945.

The number of inhabitants:

- 1939: 382,000.

- 1945: 260,000 (German population partially expelled, war losses).

Polish authorities were led by Piotr Zaremba. Many Germans had to work in the Soviet military bases that were outside Polish jurisdiction. In the 1950s most of the pre-war inhabitants were expelled from the city in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement, although there was a significant German minority for the next 10 years.

In 1945 there was already a small Polish community consisting of the few pre-war inhabitants and the Polish forced workers during World War II, who survived the war. The city was settled with the new inhabitants from every region of Poland, mainly from Pomerania (Bydgoszcz Voivodeship) and Greater Poland (Poznań Voivodeship), but also including those who lost their homes in the eastern Polish territories that were annexed by the Soviet Union, especially the city of Wilno. This settlement process was coordinated by the city of Poznań. Also Poles repatriated from Harbin, China and Greeks, refugees of the Greek Civil War, settled in Szczecin in the following years.[29][30]

Voivodeship capital in Poland (after 1945)

Old inhabitants and new settlers did a great effort to raise the Szczecin from ruins, rebuild, reconstruct and extend the city's industry, residential areas but also the cultural heritage (e.g. the Pomeranian Dukes' Castle in Szczecin), and it was still harder to do this under the communist regime. Szczecin became a major industrial centre of and a principal seaport not only for Poland (especially the Silesian coal) but also for Czechoslovakia and East Germany.

The people of Szczecin supported and raised medical supplies and donated blood for the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. In December 1956, Szczecin was the site of a mass protest against the Soviets and communist rule and in solidarity with the Hungarian Revolution. Protesters seized and demolished the Soviet consulate.[31] Protesters were later persecuted and imprisoned by the communists.[31] In 2016, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Polish solidarity with the Hungarians, the Hungarian-funded "Boy of Pest" monument was unveiled in Szczecin.[32] Szczecin together with Gdańsk, Gdynia and Upper Silesia was the main centre of the democratic anti-communist movements in first in March 1968 and December 1970. The protesters attacked and burned the Polish United Workers' Party regional headquarters and the Soviet consulate in Szczecin. The riots were pacified by the secret police and the armed forces; see: Coastal cities events. After 10 years in August 1980 the protesters locked themselves in their factories to avoid the bloody riots. The strike was led by Marian Jurczyk, leader of the Szczecin Shipyard workers and it proved successful. On 30 August 1980, the first agreement between the protesters and the communist regime was signed in Szczecin, which paved the way for the creation of the Solidarity movement, which contributed to the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe.[33] Further protests and strikes took place in 1982 and 1988.

From 1946 to 1998 Szczecin was the capital of the Szczecin Voivodeship, but the region's boundaries were redrawn in the administrative reorganizations in 1950 and 1975. Boundaries of the Szczecin City were extended by joining with Dąbie in 1948. Since 1999 it is the capital of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Communist-dominated municipal administration was replaced by a local government in 1990, and the direct election of the city president (mayor) was introduced in 2006.

Demographics

Since the medieval Christianization of the region, the population of Szczecin was largely Catholic. After the Reformation it was predominantly composed of Protestants, and since the end of World War II the majority of the population is once again composed of Catholics.

| Year | Inhabitants | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1720 | 6,081[34] | |

| 1740 | 12,360[34] | |

| 1756 | 13,533[34] | |

| 1763 | 12,483[34] | |

| 1782 | 15,372 | no Jews[34] |

| 1794 | 16,700 | no Jews[34] |

| 1812 | 21,255 | incl. 476 Catholics and five Jews.[34] |

| 1816 | 21,528 | incl. 742 Catholics and 74 Jews.[34] |

| 1831 | 27,399 | incl. 840 Catholics and 250 Jews.[34] |

| 1852 | 48,028 | incl. 724 Catholics, 901 Jews and two Mennonites.[34] |

| 1861 | 58,487 | incl. 1,065 Catholics, 1,438 Jews, six Mennonites, 305 German Catholics and three other citizens.[34] |

| 1885 | 99,475[11] | |

| 1890 | 116,228[11] | |

| 1900 | 210,680[11] | |

| 1905 | 224,119 | together with the military, incl. 209,152 Protestants, 8,635 Catholics and 3,010 Jews.[35] |

| 1910 | 236,113 | incl. 219,020 Protestants and 9,385 Catholics[12] |

| 1925 | 254,466[12] | |

| 1933 | 269,557 | |

| 1939 | 382,000 | |

| 1945 | 260,000 | after expulsion of Germans and war losses |

| 1960 | 269,000 | |

| 1975 | 369,700 | |

| 2000 | 415,748 | |

| 2009 | 408,427 | |

See also

References

- Notes

- Kowalska, Anna B; Łosiński (2004). "Szczecin: origins and history of the early medieval town". In Urbanczyk, Przemysław (ed.). Polish lands at the turn of the first and second millennium. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences. pp. 75–88.

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler Verlag, 1999, p. 34-35 (in German)

- Krasuski, Marcin (2018). "Walka o władzę w Wielkopolsce w I połowie XIII wieku". Officina Historiae (in Polish). No. 1. p. 64. ISSN 2545-0905.

- Thomas Riis, Studien Zur Geschichte Des Ostseeraumes IV. Das Mittelalterliche Dänische Ostseeimperium, 2003, p. 48

- Gustav Kratz, Die Städte der Provinz Pommern. Abriss ihrer Geschichte, zumeist nach Urkunden, Berlin, 1865, p. 383

- Kronika wielkopolska, PWN, Warszawa, 1965, p. 297 (in Polish)

- Genowefa Horoszko, Monety książąt pomorskich z historycznych kolekcji w Muzeum Narodowym w Szczecinie, "Cenne, bezcenne/utracone", Nr 1(74)-4(77), 2013, p. 21 (in Polish)

- Skrycki, Radosław (2011). "Z okresu wojny i pokoju – "francuskie" miejsca w Szczecinie z XVIII i XIX wieku". In Rembacka, Katarzyna (ed.). Szczecin i jego miejsca. Trzecia Konferencja Edukacyjna, 10 XII 2010 r. (in Polish). Szczecin. p. 95. ISBN 978-83-61233-45-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Skrycki, p. 96

- Skrycki, p. 99

- Britannica 1910.

- "Stadtkreis Stettin". Verwaltungsgeschichte.de. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Skrycki, p. 100

- Tadeusz Białecki, "Historia Szczecina" Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1992 Wrocław; pgs. 9, 20-55, 92-95, 258-260, 300-306

- Skrycki, p. 104

- Evans, Richard J. (2004). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Press. p. 399. ISBN 1-59420-004-1.

- "Robotnicy przymusowi w czasie drugiej wojny światowej". Archiwum Państwowe w Szczecinie (in Polish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Gefängnis Stettin". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "German Dulag Camps". Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Chrzanowski, Bogdan (2022). Polskie Państwo Podziemne na Pomorzu w latach 1939–1945 (in Polish). Gdańsk: IPN. pp. 47–48, 57. ISBN 978-83-8229-411-8.

- Chrzanowski, Bogdan. "Organizacja sieci przerzutów drogą morską z Polski do Szwecji w latach okupacji hitlerowskiej (1939–1945)". Stutthof. Zeszyty Muzeum (in Polish). 5: 30. ISSN 0137-5377.

- Musekamp, Jan (2010). Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin (in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-447-06273-2.

- Polonia szczecińska 1890-1939 Anna Poniatowska Bogusław Drewniak, Poznań 1961

- Musekamp, Jan: Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin, p. 74, with reference to: Edward Wlodarczyk: "Próba krytycznego spojrzenia na dzieje Polonii Szczecińskiej do 1939 roku" in Pomerania Ethnica, Szczecin 1998 Quote: "..und so musste die Bedeutung der erwähnten Organisationen im Sinne der Propaganda übertrieben werden."

- Grete Grewolls: Wer war wer in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern? Ein Personenlexikon. Edition Temmen, Bremen 1995, ISBN 3-86108-282-9, pg. 467.

- Szczecin.pl Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Zaremba in the Märkische Oderzeitung Archived 10 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine(in German)

- Eberhard Völker. Pommern und Ostbrandenburger. Langen Müller. p. 133.

- Przemysław Plecan. "Wyjątkowa wystawa o historii w chińskiej Mandżurii i jej finale w Szczecinie". TVP3 Szczecin (in Polish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Kubasiewicz, Izabela (2013). "Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości". In Dworaczek, Kamil; Kamiński, Łukasz (eds.). Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. pp. 117–118.

- "Upamiętnienie wydarzeń z 10 grudnia 1956 r". szczecin.uw.gov.pl (in Polish). 10 December 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- "W Szczecinie odsłonięto pomnik "Chłopca z Pesztu" - symbolu powstania węgierskiego". PolskieRadio24.pl (in Polish). 9 December 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- "Porozumienie szczecińskie: krok ku wolności". PolskieRadio.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Kratz (1865), pg. 405

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. 6th edition, vol. 19, Leipzig and Vienna 1909, p. 9.

Further reading

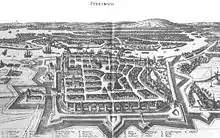

- Matthäus Merian; Martin Zeiler (1652). "Stetin". Topographia Electoratus Brandenburgici et Ducatus Pomeraniae. Topographia Germaniae (in German). Frankfurt.

- "Stettin", Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopædia Britannica Co., 1910, OCLC 14782424,

***Please note that no wikisource link is available to the EB1911 article [Stettin]***