History of Texas A&M University–Commerce

The history of Texas A&M University–Commerce began in 1889 when William L. Mayo founded a private teachers' college named East Texas Normal College in Cooper, Texas. After the original campus was destroyed in a fire in July 1894, the college relocated to Commerce. In 1917, the State of Texas purchased and transformed it into a state college, and renamed it East Texas State Normal College. Mayo died of a sudden heart attack the same day the Texas Legislature voted to buy the college, and he never heard the news. In 1923, it was renamed East Texas State Teachers College to define its purpose "more clearly", and in 1935 it began its graduate education program. From the 1920s through the 1960s, the college grew consistently, in terms of student enrollment, number of faculty, and size of the physical plant.

.jpg.webp)

The school was renamed East Texas State College in 1957, after the Legislature recognized its broadening scope beyond teacher education. It integrated in 1964 when ordered to do so by the Board of Regents. It was renamed East Texas State University in 1965, after the establishment of the institution's first doctoral program in 1962. While the student body shrank in size in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it became increasingly diverse as older non-traditional students, ethnic and racial minorities, and international students all grew in numbers. The economic downturn in Texas in the mid-1980s seriously threatened the university, leading to proposals to close it entirely before a bus trip with 450 supporters trekked to the State Capitol in a show of support that ultimately secured its continued existence. The university was renamed Texas A&M University–Commerce and admitted into the Texas A&M University System in 1996. Since 2000, growth in student enrollment has again become consistent.

The university is a charter member of the Lone Star Conference (LSC), and has won NAIA national championships in football and men's basketball. Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Sam Rayburn is perhaps its most famous alumnus.

East Texas Normal College (1889–1917)

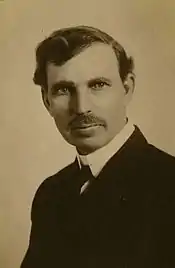

East Texas Normal College (ETNC) was founded in Cooper by Kentucky native William L. Mayo as a private teachers' college based on Normal principles.[1][2] Mayo served as the president of the institution from its foundation until his death in 1917.[3] ETNC relocated from Cooper to Commerce after its original campus was destroyed in a fire in July 1894.[1][4][5][6] One of Commerce's chief advantages was that it was well connected by rail, boasting regular service on the St. Louis Southwestern Railway of Texas ("Cotton Belt") to Dallas, Sherman, and Texarkana and on the Texas Midland Railroad to Paris, Ennis, and Houston.[6]

ETNC resumed operation in Commerce in September 1894 with just 35 students in a small rented store, although shortly thereafter it built a two-story classroom and administration building known as College Hall.[3][6][7][8] The college grew slowly but steadily during the 1890s, reaching 132 students in 1896 and 212 in 1897.[7] By 1907, ETNC had established a reputation as "the best attended summer institute for teachers in the state".[9] After moving to Commerce, the ETNC campus burned twice more, in 1907 and again in 1911.[10][11]

The early curriculum taught by ETNC reflected Mayo's own personal beliefs about education, focusing on participation and hands-on learning instead of memorization or rote learning.[12] All of the college's most popular degrees (B.S., B. Lit., and B. Ped.) required just three years of study, while only the demanding A.B. required a full four years and a rigorous "classic course".[13] Extracurricular activities for students at ETNC consisted primarily of student clubs known as "literary societies",[14] various programs organized by the college itself,[15] and athletics in the form of both intramural sports (including baseball and basketball) as well as an intercollegiate football team (despite Mayo's strong initial opposition to the concept).[15]

_2.jpg.webp)

ETNC's relative success during this period led to rivalry with other nearby colleges such as T. Henry Bridges' Henry College in Campbell,[16][17] a 1904 attempt by Denison to entice Mayo to relocate the college there for a considerable amount of financial aid,[18] and praise from perhaps its most famous alumnus, future Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Sam Rayburn.[19][20][21]

After Mayo lobbied the State of Texas to purchase ETNC and transform it into a state teachers' college,[1][3] the 35th Texas Legislature voted to buy it, despite significant opposition.[3][22] On March 14, 1917, a telegram arrived in Commerce confirming that the House of Representatives in Austin had passed the requisite bill to ensure the state purchase of ETNC by a margin of 79 to 41, and Mayo died of a sudden heart attack.[nb 1][1][23][24] Despite Mayo's unexpected death, the state purchased the college after Governor James "Pa" Ferguson signed the bill into law on April 4.[25]

By 1917, ETNC had educated more than 30,000 students, including more public school teachers than any other college or university in Texas during the same period.[3]

East Texas State Normal College (1917–1923)

.jpg.webp)

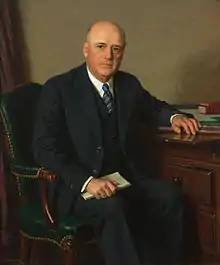

East Texas Normal College (ETNC) was renamed East Texas State Normal College (ETSNC) in 1917 after it was acquired by the State of Texas and transformed into a public college.[4][5][26] Against the backdrop of significant institutional debt, a pressing need for repairs to campus facilities, and American entry into World War I,[27] the Board of Regents selected Randolph B. Binnion, the Assistant State Superintendent of Public Instruction, as the college's second president in July 1917.[28] Among Binnion's first accomplishments in office were enlarging the faculty and repairing the physical plant: in his first year, he more than doubled the number of professors on campus by hiring 18 new faculty members,[29] and under his watch the Administration Building, Science Hall, and Willard Hall were all renovated or remodeled.[30] Despite having an enrollment of just 234 when it reopened as a public school in 1917,[30][31] by 1922 ETSNC was the second best attended normal college in the state, surpassed only by North Texas State Normal College in Denton.[32]

In the late 1910s, state normal colleges in Texas were not permitted to have on-campus dormitories, so the burden of accommodating students fell largely to Commerce citizens who were willing to host boarders.[33] In 1920, ETSNC and the other state normal colleges pressured the board of regents to permit dormitories, largely to accommodate growth at the schools.[34]

.jpg.webp)

Although Binnion generally adhered to the same principles regarding teacher education that Mayo did, ETSNC's conversion into a state school brought inevitable and extensive changes, including the reorganization of the college into four separate program "divisions".[35] The retirement of the "sub-college" program that dated back to Mayo, along with new state requirements more generally, resulted in students who had not finished high school having more difficulty gaining admittance to ETSNC, which disproportionately affected rural students.[36]

The late 1910s and early 1920s were an era of marked conservatism at ETSNC, as all prospective faculty members were asked whether they danced or belonged to a church,[37] while the school viewed itself as a surrogate parent for students in line with the principle of in loco parentis.[38] Nonetheless, student life developed during this period, which saw the formation of student government[38] in addition to ample opportunities for students to attend lectures and concerts as well as participate in extracurricular organizations.[39] ETSNC also became known for its low costs as its reputation for quality grew, exemplified by the fact that the Cleveland, Ohio, school board offered to hire its "entire output of teachers" in 1920.[40]

By the time ETSNC became a state institution in 1917, blue and gold had been adopted as its school colors, and in 1919 its teams began using the nickname "Lions".[41] During the late 1910s and 1920s, ETSNC fielded teams in football, men's basketball, women's basketball, and baseball, while the school gained admission into the Texas Intercollegiate Athletic Association in 1922.[42]

East Texas State Teachers College (1923–1957)

.jpg.webp)

East Texas State Normal College (ETSNC) was renamed East Texas State Teachers College (ETSTC) in 1923,[3][4][23][26][43] to define its purpose "more clearly".[43] In 1924, President Randolph B. Binnion resigned the presidency to become provost at George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee, and the board of regents selected ETSTC Dean of the Faculty and professor of mathematics Samuel H. Whitley as his successor.[44] In 1925, the college became a true four-year institution when its "sub-college" program was transferred to its training school.[45]

The ETSTC period was marked by growth in its faculty, student enrollment, and physical plant: ETSTC grew from 65 faculty in 1925 to 132 in 1957,[46][47] from approximately 1,000 students in 1925 to over 3,000 in 1958–59,[48][49] and from six buildings valued at roughly $500,000 in the early 1920s to a physical plant valued at over $4 million in 1949.[50][51] Under Whitley's tenure, in the late 1920s, the college built a new president's home and its first dedicated library.[52]

While in the early 1920s ETSTC's faculty generally lacked advanced degrees and was relatively poorly compensated,[53][54][55] by 1927 a majority of the faculty held degrees higher than bachelor's degrees,[53] and by 1957 59 of its 132 faculty members held doctorates.[47] All ETSTC presidents exerted a marked conservative influence on the campus; during his presidency, for instance, Whitley disapproved of smoking and refused to hire married women.[56]

During Whitley's presidency, the high school-level "sub-college" program was eliminated (in 1931),[57] there was a shift from Mayo's old quarter system to semesters,[57] and ETSTC began its graduate education program in 1935,[3][4][23] offering master's degrees in education, English, and history at its inception.[58] The ETSTC era also included the Great Depression, which caused a steep drop in enrollment[59] and witnessed federal student aid provided principally by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the National Youth Administration (NYA).[60][61][62] During World War II, the campus hosted the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC),[63][64] the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP),[63] and the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP),[65] while 63 former students were killed in the conflict.[66]

The post-World War II era at ETSTC was marked by a return to growth, in terms of the faculty,[47][67] student enrollment,[49][68] and physical plant alike.[50] New dormitories and athletics buildings, including Memorial Stadium and the Field House, were built during this period.[51][69] In October 1946, Whitley died suddenly of a heart attack while on a hunting trip;[70] his replacement was veteran East Texas State dean A. C. Ferguson, who at 69 years of age was a year away from mandatory retirement and could only serve as an interim president.[71]

In 1947, after Ferguson retired, Sam Houston State Teachers College dean James Gilliam Gee was named the fifth president of ETSTC, and he would lead with an involved, engaged, and at times impulsive style.[72][73] Gee's presidency included two major controversies: his feud with Sam Rayburn, the congressman representing Hunt County and an alumnus of the college,[74] and his support of a doctrinaire general studies program that alienated numerous faculty and resulted in the demotion of two "dissident" department heads.[75][76][77][78] Gee also was able to block integration from occurring at East Texas State for much of his presidency;[79][80] the college would not integrate until forced to do so by the Board of Regents in 1964.[79]

The 1920s and 1930s have been referred to as the "truly golden age" of student clubs at East Texas State.[39] The ETSTC era was also a banner period for athletics, as the school joined the Lone Star Conference (LSC) as a founding member in 1931.[81][82] During the "Golden Fifties" both the football and men's basketball teams won multiple conference championships,[80][83] and the basketball team won the NAIA national basketball tournament in 1954–55.[80][84]

East Texas State College (1957–1965)

.jpg.webp)

East Texas State Teachers College (ETSTC) was renamed East Texas State College (ETSC) in 1957,[3][4][23][26] after the Texas Legislature recognized the broadening scope of the institution beyond teacher education.[3][4][23] The ETSC era witnessed substantial growth in student enrollment, from approximately 3,100 students in 1958–59 to 6,810 in fall 1965.[49][68] It also saw a significant development of the college's physical plant under President Gee: a new library,[49] student center,[85] and multiple dormitories were built,[86] and by 1966 the value of the school's buildings exceeded $22 million.[87] Academic developments during this period were also significant, including the establishment of an honors program in 1961,[78] the authorization to grant doctorates in English and education from 1962,[23][67][88] and a continued increase in the percentage of ETSC professors holding Ph.D.s, growing from roughly 45% in 1957 to 58% in 1966.[47]

ETSC integrated on June 6, 1964 when ordered to do so by the Board of Regents, and Velma Waters became the first African American undergraduate student at the college, while Charles Garwin became the first African American graduate student as well as the first to graduate (in January 1966).[79] Students were still subject to the principle of in loco parentis and its related curfews, dress codes, and strict enforcement of regulations,[89] although they also enjoyed events such as Kappa Delta Pi's spelling bee, a Mexican-themed "Down South Week", and an antebellum-themed "Old South Week".[90] 1959 alone witnessed the lifting of a long-standing ban on national fraternities and sororities and the establishment of a Forum Arts Program that brought "distinguished speakers and cultural attractions" to campus.[91]

East Texas State University (1965–1996)

.jpg.webp)

East Texas State College (ETSC) was renamed East Texas State University (ETSU) on March 30, 1965, when Governor John Connally signed House Bill 333,[88][92][93] after the establishment of the institution's first doctoral program in 1962.[3][4] After President James G. Gee retired in 1966, he was replaced by D. Whitney Halladay, a native Californian and the dean of students at the University of Arkansas.[94] By 1972, Halladay's building campaign, which followed on the heels of Gee's highly successful expansion of the physical plant, had constructed the Administration/Business Administration Building, three major dormitories, the Journalism/Graphic Arts Building, a new president's house, and the Student Affairs Building,[3][95] as well as pedestrian malls.[96]

In spring 1972, President Halladay resigned suddenly after his wife's suicide. Vice President for Administration F. H. "Bub" McDowell was named the next president of the university, despite his lack of a doctoral degree or administrative experience at any school other than East Texas State.[97] In January 1982, after reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70, McDowell stepped down from his post,[98] and Georgia Southern College vice president for academic affairs Charles J. Austin was named his successor.[99] After Austin accepted the position of head of the Department of Health Care and Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's medical school in 1986,[100] Arkansas native and ETSU vice president for academic affairs Jerry D. Morris was named the next university president on January 1, 1987.[101][102]

The ETSU period witnessed substantial swings in student enrollment, which grew from 8,890 in 1968 to 9,981 in 1975 before falling to 6,342 in 1986 and partially recovering to 8,000 in 1992.[103][104][105] The university's physical plant expanded steadily throughout the period, from 87 buildings on 150 acres (61 ha) valued at $19 million in 1965 to a campus spanning 1,883 acres (762 ha) worth approximately $150 million by the 1990s.[3]

Major structural changes to the university during the ETSU era included the creation of a separate ETSU board of regents in 1969[103] and the approval to open a branch campus in Texarkana in April 1971.[106] While at times accused of cronyism and wasteful spending,[96][97][107] the university administration pursued innovative programs that provided counseling and tutoring to disabled and minority students as well as supported disadvantaged local minority high school students while also joining consortia such as the Federation of North Texas Area Universities.[108][109][110] The administration first lowered ETSU's academic standards for admission before then raising them in successive efforts to end its enrollment crisis.[99][110] The most serious threat to face ETSU stemmed from the economic downturn in Texas in the mid-1980s,[111] which led to proposals to close the school entirely before a bus trip with 450 supporters trekked to the State Capitol in a show of support that ultimately secured the school's continued existence.[112][113]

.jpg.webp)

As the student body shrank in size in the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, it became increasingly diverse as older non-traditional students, ethnic and racial minorities, and international students all grew in numbers.[114] Through the African-American Student Society at East Texas (ASSET), the university's African American students advocated their demands for equal treatment in housing, course offerings in African American history and literature, and the employment of African American faculty members;[115] ultimately, the latter demand resulted in the first African American faculty member (David Talbot) and administrator (Ivory Moore) being hired in 1968 and 1972, respectively.[116][117] Similarly, the proportion of female faculty members grew from 20% in 1975 to almost 26% in 1990, while the first woman to hold a high-level academic office (Donna Arlton) was promoted in 1987.[105]

In 1975, campus FM radio station KETR was created, and it was joined by local cable television channel KETV in 1979.[118] ETSU's football team won the NAIA national championship in 1972,[119][120] while Lion football players such as Autry Beamon, Harvey Martin, Dwight White, and Wade Wilson went on to star in the National Football League (NFL).[120][121][122][123][124] The men's tennis team won the 1972 and 1978 NAIA national championships,[125] while future Olympian John Carlos competed for the men's track team in 1966–67.[123][126][127] After the passage of Title IX in 1972, ETSU fielded women's teams in basketball, tennis, track, and volleyball,[128] with the volleyball team achieving the most success during the period.[128][129]

Texas A&M University–Commerce (1996–present)

.jpg.webp)

In 1996, East Texas State University (ETSU) was admitted into the Texas A&M University System (TAMUS) and renamed Texas A&M University–Commerce (A&M–Commerce), during the tenure of President Jerry D. Morris.[23][130] In 1998, graduate school dean Keith D. McFarland was named his successor as the 10th president in the history of A&M–Commerce.[131] In July 2008, Dan R. Jones succeeded McFarland as the 11th president of the university, after serving as provost and vice president at Texas A&M International University (TAMIU) in Laredo.[132][133][134] On April 29, 2016, Jones died unexpectedly, in what university police later reported was a suicide.[135][136] On May 6, TAMIU president Ray M. Keck was named interim president of A&M–Commerce,[137] and he was officially named its permanent president on November 10.[138]

The A&M–Commerce era has been marked by continued growth in student enrollment, from 7,400 in 2000 to 10,000 in 2010 before exceeding 13,000 in 2015.[132][139][140] Additionally, the university's physical plant has been augmented by numerous new buildings since 1996, most notably the Morris Recreation Center (opened in 2003), the Keith D. McFarland Science Building (2006), the Rayburn Student Center (2009), and the Music Building (2011).[141][142][143][144] In 2016, the university's Carnegie Classification was upgraded to "Doctoral University-Higher Research Activity" (R2),[145] due in part to an Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) Summer Faculty Fellowship and Fulbright Scholarships awarded to its faculty.[146][147][148][149]

.jpg.webp)

A&M–Commerce has become increasingly diverse during this period, most notably in terms of Hispanic students, who have grown from approximately 7% of the student body in 2008 to about 18% in 2015,[150] which allowed the university to be designated an "emerging" Hispanic-serving institution (HSI) in 2014.[151] A&M–Commerce has also created an Honors College, an equine program, and a nursing program since 1996.[152][153][154] Additionally, it has increasingly collaborated with area junior colleges such as Eastfield College, Navarro College, Paris Junior College, and Tyler Junior College.[23][155][156][157][159]

The university's football team and men's basketball team have set numerous records and won multiple Lone Star Conference (LSC) titles since 1996.[160][161][162] Its relatively new programs in women's soccer and softball have also become highly competitive, likewise winning conference championships and qualifying for national NCAA Division II tournaments.[163][164][165][166][167][168]

Notes

- Harper, Jr., Cecil (July 6, 2015). "Mayo, William Leonidas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 3

- Young, Nancy Beck (June 15, 2010). "Texas A&M University–Commerce". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- "History & Traditions". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- Board of Regents of the Texas State Teachers Colleges (1919). Fourth Biennial Report of the Texas State Normal Schools for the Year Ending August 31, 1917, and August 31, 1918. Austin, Texas: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co. p. 4.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 4

- Reynolds 1993, p. 6

- Sawyer 1979, pp. 4

- Reynolds 1993, p. 8

- Reynolds 1993, p. 17

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 18–19

- Reynolds 1993, p. 10

- Reynolds 1993, p. 13

- Reynolds 1993, p. 21

- Reynolds 1993, p. 23

- Reynolds 1993, p. 14

- Sawyer 1979, pp. 8

- Reynolds 1993, p. 16

- "RAYBURN, Samuel Taliaferro". United States House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- Dunham, Richard (January 6, 2010). "Today in Texas history: Sam Rayburn is born". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- Sawyer 1979, pp. 7

- Reynolds 1993, p. 26

- Babb, Milton (2010). Historic Hunt County: An Illustrated History. San Antonio, Texas: HPN Books. p. 64. ISBN 1935377167.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 27

- Reynolds 1993, p. 28

- Songe, Alice H. (1978). American Universities and Colleges: A Dictionary of Name Changes. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. p. 61. ISBN 0810811375.

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 29–31

- Reynolds 1993, p. 32

- Reynolds 1993, p. 33

- Reynolds 1993, p. 34

- Reynolds 1993, p. 36

- Sawyer 1979, p. 32

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 36–37

- Reynolds 1993, p. 37

- Reynolds 1993, p. 44

- Reynolds 1993, p. 45

- Sawyer 1979, p. 25

- Reynolds 1993, p. 53

- Reynolds 1993, p. 55

- Sawyer 1979, p. 27

- Reynolds 1993, p. 49

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 51–53

- Reynolds 1993, p. 46

- Reynolds 1993, p. 60

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 46–47

- Sawyer 1979, p. 42

- Reynolds 1993, p. 118

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 63–64

- Reynolds 1993, p. 109

- Sawyer 1979, p. 40

- Reynolds 1993, p. 108

- Reynolds 1993, p. 66

- Reynolds 1993, p. 70

- Reynolds 1993, p. 69

- Sawyer 1979, p. 55

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 70–72

- Reynolds 1993, p. 72

- Reynolds 1993, p. 73

- Reynolds 1993, p. 74

- Reynolds 1993, p. 75

- Sawyer 1979, p. 80

- Sawyer 1979, p. 62

- Reynolds 1993, p. 95

- Sawyer 1979, p. 83

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 96–97

- Reynolds 1993, p. 97

- Reynolds 1993, p. 117

- Reynolds 1993, p. 99

- Reynolds 1993, p. 106

- Reynolds 1993, p. 98

- Reynolds 1993, p. 103

- Reynolds 1993, p. 105

- Reynolds 1993, p. 104

- Reynolds 1993, p. 122

- Reynolds 1993, p. 119

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 119–120

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 120–121

- Reynolds 1993, p. 121

- Reynolds 1993, p. 139

- Reynolds 1993, p. 137

- Reynolds 1993, p. 89

- Blevins, Dave (2012). College Football Awards: All National and Conference Winners Through 2010. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 242. ISBN 0786448679.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 136

- "1955 National Champs to be honored on Saturday". KETR. February 19, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 111–112

- Reynolds 1993, p. 111

- Reynolds 1993, p. 112

- Sawyer 1979, p. 94

- Reynolds 1993, p. 127

- Reynolds 1993, p. 132

- Reynolds 1993, p. 133

- Reynolds 1993, p. 140

- General and Special Laws of the State of Texas, Volume 1. Austin, Texas: Secretary of State of Texas. 1965. p. 136.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 141

- Reynolds 1993, p. 145

- Reynolds 1993, p. 147

- Reynolds 1993, p. 176

- Reynolds 1993, p. 181

- Reynolds 1993, p. 182

- Reynolds 1993, p. 188

- Reynolds 1993, p. 189

- Harvey, Scott. "Memorial service set for President Emeritus Morris". KETR. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 142

- Reynolds 1993, p. 168

- Reynolds 1993, p. 192

- Reynolds 1993, p. 149

- West, Richard (June 1974). "The Texas Monthly Reporter". Texas Monthly. ISSN 0148-7736. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 177

- Peterson's Graduate Programs in the Humanities, Arts & Social Sciences, Book 2. Peterson's Guides. 1995. p. 1375. ISBN 1560793813.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 178

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 186–187

- Reynolds 1993, p. 187

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 187–188

- Reynolds 1993, p. 170

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 170–172

- Reynolds 1993, p. 172

- Evans, Rachel (October 16, 2013). "Ivory Moore portrait unveiled at A&M-Commerce". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 167

- Reynolds 1993, p. 159

- Merrill, Durwood; Dent, Jim (1998). You're Out and You're Ugly, Too!: Confessions Of An Umpire With An Attitude. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 67. ISBN 0312182376.

- Dempsey, John Mark (September 6, 2013). "The five (or six) greatest Lions". KETR. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Harvey, Scott (June 25, 2012). "LSC Hall of Honor chooses former ETSU Defensive Back Autry Beamon". KETR. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 175

- "Lion football to hold camp in AT&T Stadium with SEC power Arkansas staff as guest coaches". The Commerce Journal. May 19, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, pp. 159–160

- Hale, George (September 2, 2016). "Olympian and former ETSU student-athlete reflects on protest, then and now". KETR. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- Slinkard, Caleb (November 11, 2011). "Famous athlete, activist John Carlos visits A&M-Commerce". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Reynolds 1993, p. 161

- "University announces five Hall of Fame inductees". The Commerce Journal. October 4, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Strickland, Jay (July 2, 2014). "Morris memorial McFarland". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Harvey, Scott (August 9, 2012). "A&M-Commerce Science Building to Bear McFarland's Name". KETR. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Haslett, Mark (April 29, 2016). "Dr. Dan Jones, Texas A&M University-Commerce president, dies". KETR. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Markon, John (April 29, 2016). "A&M-Commerce announces death of President Dr. Dan Jones". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- "Hunt County Alumni To Host Reception for Jones". Texas A&M University–Commerce. November 6, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Haslett, Mark (July 6, 2016). "University Police Report: Jones Death Was Suicide". KETR. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Seltzer, Rick (July 8, 2016). "A President's Suicide". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- Rodriguez, Mary Grace (May 6, 2016). "Texas A&M University System Names Dr. Ray M. Keck as Interim President At Texas A&M University-Commerce". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Rodriguez, Mary Grace (November 10, 2016). "Keck Named Permanent President". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Haslett, Mark (March 22, 2013). "McFarland honored at science building naming". KETR. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Fox, Anne (September 4, 2015). "Texas A&M University-Commerce reaches highest enrollment ever". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Miller, Andi (May 7, 2012). "Creating Wellness". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Harvey, Scott (August 13, 2012). "A&M-Commerce to add Rockwall to Instructional Sites". KETR. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Anderson, Torie Michelle (September 8, 2014). "A&M-Commerce Named a 'Fastest-Growing College'". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Harvey, Scott (October 17, 2011). "Performances to highlight Music Building dedication". KETR. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Wray, Sara (March 4, 2016). "University Gets New Ranking by the Carnegie Classification 2015 Update". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Wray, Sara (March 25, 2016). "Dr. Sakoglu Awarded With U.S. Air Force Research Lab Summer Faculty Fellowship". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Sopha, Sydni (December 19, 2011). "History Professor Awarded Fulbright". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Duckworth, Taelor (May 8, 2013). "Doctoral Candidate Receives Fulbright Scholarship". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Morrow, Kathleen (February 19, 2015). "Prestigious Fulbright Scholarship awarded to Dr. Carlos Bertulani". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Knight, Jerrod (November 6, 2015). "Jones, Fuentes Discuss Hispanic Enrollment Growth". KETR. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Anderson, Torie Michelle (May 8, 2014). "A&M-Commerce Ranks in Hispanic Outlook's Top 100". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- Gessner, Julia (May 9, 2016). "Honors College Students Move On to Prestigious Graduate Programs". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Walker, Sydni (September 11, 2013). "New Equine Arena Dedicated at A&M-Commerce". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "University Announces New Bachelor of Science in Nursing Degree". KETR. October 26, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "A&M-Commerce Wins Grant for Community College Scholarships". Texas A&M University–Commerce. July 29, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Harvey, Scott (May 30, 2012). "Agreement between PJC and A&M-C to benefit aspiring engineers". KETR. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Anderson, Torie Michelle (December 16, 2013). "A&M-Commerce Partners with Tyler Junior College". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Gessner, Julia (December 18, 2015). "Eastfield College Articulation Agreement Signing". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Miller, Andi (September 5, 2014). "Lions Open Season in Record-Breaking Fashion". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Champion, Rand (December 11, 2012). "Head Basketball Coach's Drive to Surpass A&M-Commerce Record". KETR. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Gessner, Julia (March 9, 2015). "Lions Win Fourth LSC Tournament Championship, Williams Named MVP". Texas A&M University–Commerce. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- "Lions soccer team returns to LSC tournament". KETR. November 5, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Chandler, Chris (November 13, 2014). "Lions celebrate third LSC tournament victory". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- "Lions earn sixth seed in NCAA South-Central Regional". KETR. November 12, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Hamrick, Joseph (May 20, 2013). "Softball to be newest sports addition to A&M-Commerce". The Commerce Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Welch, Cooper (July 17, 2013). "Bruister to be first A&M-Commerce softball coach". KETR. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "A&M-Commerce finishes historical regular season; three named to all-LSC team". The Commerce Journal. May 5, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

References

- Reynolds, Donald E. (1993). Professor Mayo's College: A History of East Texas State University. Commerce, Texas: East Texas State University Press. ISBN 0963709208.

- Sawyer, William E. (1979). History of East Texas State University. Wolfe City, Texas: Henington Publishing Company.