History of rugby league

The history of rugby league as a separate form of rugby football goes back to 1895 in Huddersfield, West Riding of Yorkshire when the Northern Rugby Football Union broke away from England's established Rugby Football Union to administer its own separate competition.[3] Similar schisms occurred later in Australia and New Zealand in 1907. Gradually the rugby played in these breakaway competitions evolved into a distinctly separate sport that took its name from the professional leagues that administered it. Rugby league in England went on to set attendance and player payment records and rugby league in Australia became the most watched sport on television. The game also developed a significant place in the culture of France, New Zealand and several other Pacific Island nations, such as Papua New Guinea, where it has become the national sport.

Rugby union before the schisms

Although many forms of football had been played across the world, it was only during the second half of the 19th century that these games began to be codified. In 1871, English clubs playing the version of football played at Rugby School, which involved much more handling of the ball than in association football, met to form the Rugby Football Union. Many new rugby clubs were formed, and it was in the Northern English counties of Lancashire and Yorkshire that the game really took hold. Here rugby was largely a working class game, whilst the south eastern clubs were largely middle class.

Rugby spread to Australasia, especially the cities of Sydney, Brisbane, Christchurch and Auckland. Here too there was a clear divide between the working and more affluent upper-class players.

The strength of support for rugby grew over the following years, and large paying crowds were attracted to major matches, particular in Yorkshire, where matches in the Yorkshire Cup (T'owd Tin Pot) soon became major events. England teams of the era were dominated by Lancashire and Yorkshire players. However these players were forbidden to earn any of the spoils of this newly-rich game. Predominantly working class teams found it difficult to play to their full potential because in many cases their time to play and to train was limited by the need to earn a wage. A further limit on the playing ability of working class teams was that working class players had to be careful how hard they played. If injured, they had to pay their own medical bills and possibly take time off work, which for a man earning a weekly wage could easily lead to financial hardship.

The schism and the birth of rugby league

In 1892, charges of professionalism were laid against rugby football clubs in Bradford and Leeds, both in Yorkshire, after they compensated players for missing work. This was despite the fact that the English Rugby Football Union (RFU) was allowing other players to be paid, such as the 1888 British Isles team that toured Australia, and the account of Harry Hamill of his payments to represent New South Wales (NSW) against England in 1904.

In 1893 Yorkshire clubs complained that southern clubs were over-represented on the RFU committee and that committee meetings were held in London at times that made it difficult for northern members to attend. By implication they were arguing that this affected the RFU's decisions on the issue of "broken time" payments (as compensation for the loss of income) to the detriment of northern clubs, who made up the majority of English rugby clubs. Payment for broken time was a proposal put forward by Yorkshire clubs that would allow players to receive up to six shillings (30p) (equivalent to £35 in present-day terms)[4] when they missed work because of match commitments. The idea was voted down by the RFU.

In August 1893, Huddersfield signed star players George Boak and John 'Jock' Forsyth from Carlisle-based club, Cummersdale Hornets.[5] The transfer was sudden and both men were summoned to appear before Carlisle Magistrates' Court for leaving their jobs without giving proper notice.[6] Huddersfield was also accused of offering cash inducements for the players to move clubs contrary to the strict rules of the RFU. After an investigation, Huddersfield eventually received a long suspension from playing matches.

The severity of the punishments for "broken time" payments and their widespread application to northern clubs and players contributed to a growing sense of frustration and absence of fair play. Meanwhile, there was an obvious comparison with the professional Football League which had been formed in 1888, comprising 12 association football clubs, six of whom were from Northern England. In this environment, the next logical step was for the northern rugby clubs to form their own professional league.

On 27 August 1895, as a result of an emergency meeting in Manchester, prominent Lancashire clubs Broughton Rangers, Leigh, Oldham, Rochdale Hornets, St. Helens, Tyldesley, Warrington, Widnes and Wigan declared that they would support their Yorkshire colleagues in their proposal to form a Northern Union.

For several years past, the Yorkshire clubs have been endeavouring to secure a sufficient relaxation of the laws to permit the payment to players of actual out of pocket expenses (including loss of wages) incurred whilst playing for their clubs, but every proposition to that effect has been successfully combatted by the Southern clubs, who object to the innovation as being the introduction of the thin end of professionalism pure and simple. And this is really the gist of the whole matter.

New Zealand's Observer Newspaper, 26 October 1895[7]

.jpg.webp)

Two days later, on 29 August 1895, representatives of twenty-two clubs met in the George Hotel, Huddersfield, to form the Northern Rugby Football Union, usually called the Northern Union (NU). This was effectively the birth of rugby league, the name adopted by the sport in 1922.[8] Twenty clubs had agreed to resign from the Rugby Union, but Dewsbury felt unable to comply with the decision. The Cheshire club, Stockport, had telegraphed the meeting requesting admission to the new organisation and was duly accepted with a second Cheshire club, Runcorn, admitted at the next meeting.

The twenty-two clubs and their years of foundation were Batley 1880; Bradford 1863; Brighouse Rangers 1878; Broughton Rangers 1877; Halifax 1873; Huddersfield FC 1864; Hull F.C. 1865; Hunslet 1883; Leeds 1870; Leigh 1878; Liversedge 1877; Manningham 1876; Oldham 1876; Rochdale Hornets 1871; Runcorn 1895; Stockport 1895; St Helens 1873; Tyldesley 1879; Wakefield Trinity 1873; Warrington 1876; Widnes 1875; and Wigan 1872.

The rugby union authorities took drastic action, issuing sanctions against clubs, players and officials involved in the new organisation. This extended even to amateurs who played with or against Northern Union sides. Consequently, northern clubs that existed purely for social and recreational rugby began to affiliate to the Northern Union, whilst retaining amateur status. By 1904 the new body had more clubs affiliated to it than the RFU.

The separate Lancashire and Yorkshire competitions of the NRFU merged in 1901, forming the Northern Rugby Football League. Also in 1901, James Lomas became the first £100 transfer, from Bramley to Salford. The NRFU became the Northern Rugby Football League in the summer of 1922.

Similar schisms in football were threatened by the formations of the British Football Association in 1884 and the Amateur Football Association in 1907, but were averted.

The historic events that led to the 1895 rugby split were the subject of Mick Martin's play Broken Time, the first dramatic treatment of rugby league.[9]

Development of rugby league in Great Britain

The first international rugby league match took place in 1904 between England and an Other nationalities team, mostly made up of Welsh players.[10]

Initially the Northern Union continued to play under existing RFU laws. The first minor change (awarding a penalty for a deliberate knock-on) was introduced during the first season of the game. Other new laws were gradually introduced until, by the arrival of the All Golds in 1907 the major differences between the games had been introduced. These major differences were:

- 13 players per team as opposed to 15 in union (the two "missing" are the flankers)

- The "play the ball" (heeling the ball back after a tackle) rather than a ruck

- The elimination of the line-out

- A slightly different scoring structure, with all goals only being worth 2 points

See: Rugby league gameplay for more on the current game.

During this period the Northern Union began to develop the British game's major tournaments. The league championship, after initially being played as one competition, was split into two sections, the Lancashire and Yorkshire leagues, with only a limited number of inter-county games. This necessitated a play-off structure to determine the overall champions. A nationwide cup, the Challenge Cup was introduced, and soon became the biggest draw in the sport. Finally, in 1905, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cups were introduced, thus completing a structure that was to last until the 1960s. There were therefore four trophies on offer to any one club, and the "Holy Grail" was to win "All Four Cups".

As it became obvious that two codes of rugby were going to co-exist for the foreseeable future, those interested in the game needed to be able to distinguish between them. It became customary to describe those teams affiliated to the NU as 'playing in the league' hence "rugby league" while those which remained affiliated to the RFU (who did not play in a league) as playing "rugby union".

Introduction to New Zealand

In 1905, as New Zealand's rugby union team, the All Blacks, toured Britain, they witnessed first-hand the growing popularity of the Northern Union games. In 1906, All Black George William Smith, while on his way home, met an Australian entrepreneur, J. J. Giltinan to discuss the potential of professional rugby in Australasia.

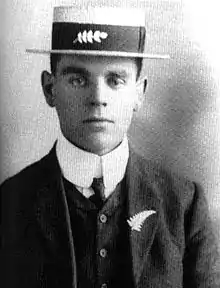

In the meantime, a less-well known New Zealand rugby union player, Albert Henry Baskerville (or Baskiville), was about to recruit a group of players for a professional tour of Great Britain. It is believed that Baskerville first became aware of the profits to be made from such a venture while he was working at the Wellington Post Office in 1906: a colleague had a coughing fit and dropped a British newspaper. Baskerville picked it up and noticed a report about a Northern Union match that over 40,000 people had attended. Baskerville wrote to the NRFU asking if they would host a New Zealand touring party. George Smith learned of Baskerville's activities and they joined forces to recruit a team.

All Golds tour

When the All Golds stopped off in Australia, three games were played at the Sydney Showground, against a professional NSW rugby team. These games were played under rugby union laws, as no copies of the Northern Union laws were available. Baskerville was greatly impressed by Dally Messenger, and persuaded him to join the touring party. For this reason, the All Golds are sometimes known as Australasia, rather than New Zealand, although Messenger was the only Australian in the touring team.

The All Golds arrived in Britain late in 1907 having never even seen a match played under the new Northern Union laws. They undertook a week's intensive coaching in Leeds to bring them up to speed, and after playing a number of touring matches the first true rugby league test was played, with the team going down 8–9 to Wales in Aberdare on 1 January 1908. The All Golds gained revenge however, defeating the full Great Britain side in two of the three Test matches, which were played at Leeds, Chelsea and Cheltenham; a surprising choice of venues given rugby league's northern base. The tour was a great success, and gave a much needed boost to the game in Britain, which was struggling financially against the rise of association football.

Baskerville died from illness on the Australian leg of the tour, but the professional rugby movement lived on, pushing forward in New Zealand despite strong opposition from the rugby union establishment.

Early setbacks for the game in New Zealand

Apart from the blow presented by the sudden and premature death of Baskerville, other difficulties would soon trouble the game in New Zealand. In some ways, the All Golds were too successful for the good of New Zealand rugby league, as many team members soon accepted lucrative contracts with British clubs. Baskerville's game would soon establish a strong following, especially in Auckland, but rugby union's strong grassroots organisation and finances in New Zealand—its "veiled professionalism" in the eyes of many observers at the time—meant that rugby league was unable to become quite as dominant there as in some regions of Australia and England.

...the game is but a recreation, and no recreation should become a business. But a man is perfectly justified in fortifying himself against being out of pocket when following recreative purposes. There can be no valid objection to a player being paid his actual out-of-pocket purposes while on tour—provided, of course, this course is not abused. If the Northern Union game is to be popularised in New Zealand, its promoters must make such provisions as will keep it free from such abuses. It must be entirely free from straight-out bastard professionalism.

Introduction to Australia

New South Wales

In the Australian rugby stronghold of Sydney, issues of class and professionalism were beginning to cause friction. Rumours and claims of "shamateurism" (see Amateur sports) in the New South Wales Rugby Union were circulating. The growing tension was exacerbated by an incident in 1907, when a working class player, Alex Burdon, broke his arm while playing for the New South Wales team, and received no compensation for his time off work.

George Smith cabled a friend in Sydney to enquire whether there might be any support for a tour by his New Zealand professional team. Word reached Giltinan, who took great interest. Giltinan announced that he had invited Baskerville's team to play three matches in Sydney. The Australian press responded by dubbing the travelling New Zealand team "All Golds", a sardonic play on the nickname of the existing amateur New Zealand rugby team, the "All Blacks" and the supposed "mercenary" nature of the new code. The games were a great success; leaving the rugby rebels of Australia with much needed funds which soon proved to be vital for rugby league in Australia.

A meeting was held at Bateman's Crystal Hotel in Sydney on 8 August 1907, to organise professional rugby in Australia. Giltinan, Burdon and the Test cricketer Victor Trumper were among those who attended. The meeting resolved that a "New South Wales Rugby Football League" (NSWRFL) should be formed, to play the Northern Union rules. This was the first time that the words "rugby" and "league" were used in the name of an Australian organising body. Players were soon recruited for the new game; despite the threat of immediate and lifetime expulsion from the New South Wales Rugby Union. The NSWRFL managed to recruit Herbert "Dally" Messenger, the most famous rugby player in Sydney at the time.

The first season of the NSWRFL competition was played in 1908, and has continued to be played every year since (despite changes in administration and name), eventually going national and becoming the world's premier rugby football club competition.

That [the touring New Zealand side] is a professional team makes little difference to the crowd of Sydney people who want to see football. That it plays the Northern Union game is in its favour with the crowd. The Sydney newspapers are, generally speaking, supporters of the Rugby Union game. Nevertheless, their notices have been most favourable. "A brilliant game." "Intense excitement." "The crowd roared itself hoarse." "One of the most exciting games ever seen in Sydney."

In September 1909, when the new "Northern Union" code was still in its infancy in Australia, a match between the Kangaroos and the Wallabies was played before a crowd of around 20,000, with the Rugby League side winning 29–26.[13] That year rugby union and rugby league had similar gate receipts. By 1910 league's had doubled and by 1913 rugby union's receipts were less than 10% of its competitors'. Union had to relinquish leases on major sporting grounds, with most being taken over by rugby league.[14]

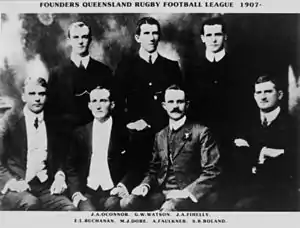

Queensland

The All Golds tour also served to kick start the game in the Australian state of Queensland, the great rival of NSW in rugby. On 16 May 1908, the returning New Zealanders played a hastily assembled Queensland team in Brisbane. Observers of the new game were shocked when Albert Baskerville fell ill in Brisbane and died of pneumonia. Test series between Great Britain and New Zealand are played for the Baskerville Shield, named in his memory.

A Queensland Rugby Football Association was founded, and in early July, informal club games were played in Brisbane. Later that month there were three representative games against NSW, and these acted as selection trials for a national team. The first game was also notable for a Queensland tackle which rendered one NSW player, Ed "Son" Fry, completely naked from the waist down—an event which did not stop him from scoring a try.

The Brisbane Rugby League premiership began in 1909. On 8 May the first match was played in Brisbane between Norths and Souths before a handful of spectators at the Gabba.[15]

By the 1920s the Queensland Rugby League had established itself as a force to rival the NSWRL.

Rugby league's "Ashes"

Also in 1908, the Australian rugby union team returned from a tour of the British Isles, for which the team had received three shillings a day, for out-of-pocket expenses. Thirteen of the players immediately joined rugby league teams. By the northern winter of 1908–09, an Australian touring party was heading for Great Britain, and the test series was dubbed "The Ashes" by the press, in imitation of The Ashes cricket matches, contested by Australia and England.

Later in 1909, when New Zealand toured Australia, the home team's jersey featured a kangaroo for the first time, giving them the enduring nickname of "The Kangaroos".

Pre-war developments

The early years of the 20th century also saw attempts to establish the game in Wales, with several teams being formed in the country. None of these ventures lasted long, however Wales remained a source of playing talent for rugby league. Over the years many hundreds of Welsh rugby union players "moved north" to the major English clubs, attracted by the opportunity to earn money playing rugby. (It was not until rugby union officially allowed professionalism, in the late 20th century that this supply of talent ceased.)

The 1910 Great Britain Lions tour of Australia and New Zealand, the first ever, took place after the 1909–10 Northern Rugby Football Union season and featured a number of Welsh former rugby union internationals. Several Wallabies players changed codes to play against this touring team, which was anticipated to be one of the best sides ever to visit Australasia.

The Rugby League matches continue to command more public interest than the Union.

In Australasia, the game centred around local, regional or statewide leagues, and there were no national competitions in either country until late in the 20th century. In both Australia and New Zealand, club championships were based on one set of home and away matches leading to a play-off, rather than the multiplicity of trophies available to British clubs. Rugby league quickly took over from rugby union as the most popular form of football in New South Wales and Queensland. The rest of the country was already dominated by Australian rules football. The amateur code still held sway in New Zealand, although the emergence of rugby league meant that it was no longer unrivalled in popularity.

Sport in general suffered as a result of the First World War, and rugby league was no exception. In Britain, the government discouraged all professional sports, and the major competitions were abandoned. In Australia, the situation was slightly less serious, and rugby league continued. The rugby union authorities opted to suspend play throughout the war, and this decision is often cited as one of the prime reasons for the traditional dominance of rugby league over rugby union in Australia.

Although the clubs continued to play, many of them were short of players due to the fighting. In 1917, Australia's first rugby league club, the Glebe "Dirty Reds" (founded on 9 January 1908), unleashed controversy when it fielded a player named Dan "Laddo" Davies. Local rivals Annandale protested that Davies lived within their designated recruiting area. Glebe were deducted two competition points and Davies received a lifetime ban. Many Glebe players already believed the NSWRL was biased against them and they went on strike; the league responded by suspending the first grade team until the following April. Davies returned to his native Newcastle, where his previous club, Western Suburbs—not to be confused with the Sydney club of the same name—sought to use him in the local league. They tried repeatedly to have Davies' suspension lifted, but the NSWRL refused. When Western Suburbs fielded him in a match the NSWRL disqualified most of the local officials for a year. Disgruntled Novocastrians formed a breakaway competition, which lasted until 1919. The fortunes of Glebe, both on the field and financially, did not improve greatly after the Davies affair, and it was expelled from the main NSWRL competition in 1929.

In November 1921 in England, the first £1,000 transfer fee took winger Harold Buck from Hunslet to Leeds.

Internationally, the game had settled into a steady pattern of alternating tours, with either Australia or New Zealand visiting Britain once every two years, and Britain reciprocating in the southern hemisphere. The war had intervened, but the schedule was picked up again after hostilities ceased.

An increasing number of Australian and New Zealand players headed for the bigger pay packets on offer in England, many of them destined never to be seen again on the playing fields of their home countries.

In 1933 a proposed hybrid sport of rugby league and Australian rules football was trialled only once.

Inter-war years

For many years, the rugby union authorities had suspected that the French rugby union was abusing the idea of amateurism, and in the early 1930s the French Rugby Union was suspended from playing against the other nations. In 1932 the first rugby league match under floodlights is played between Leeds and Wigan at White City in London.[17] Following development work by both Harry Sunderland (on behalf of the Australian Rugby League) and the Rugby Football League based in England, the Australian and Great British Test teams played an exhibition game at Stade Pershing in Paris in late December 1933. The French Rugby League was formed on 6 April 1934.[18]

Looking round for an alternative, many French players turned to rugby league, which soon became the dominant game in France, particularly in the south west of the country. The arrival of a French team on the international scene allowed more variety in the touring pattern, and also for the introduction of a European Championship.

During the Second World War, the British government took a more benign view of professional sports, viewing them as a vital aid to public morale. Although normal leagues were suspended, a War Emergency League was established, with clubs playing separate Yorkshire and Lancashire sections to reduce the need for travel. This period also saw a temporary relaxation of the regulations prohibiting rugby union players from contact with rugby league. In an extraordinary development a team representing rugby league met a rugby union equivalent in two matches, held to raise money for the Red Cross. Both games were held under rugby union rules; both were won by the rugby league side.

In Australia, the war years produced large crowds, and financially at least, the sport did not suffer the hardships endured during the First World War. Nonetheless, the loss of many young men in fighting undoubtedly weakened the talent pool available.

The defeat of France had serious implications for rugby league in France. The Vichy regime banned rugby league and forced players, clubs and officials to switch codes to union. Assets of the rugby league and its clubs were handed over to union.

The consequences of this action still reverberate; the assets were never returned, and although the ban on rugby league was lifted, it was prevented from calling itself rugby from 1949 to the mid-1980s, having to use the name Jeu à Treize (Game of Thirteen, in reference to the number of players in a rugby league side).

Post-war developments

The rules of the sport had continued to evolve, and until the 1940s there was no world governing body to oversee this and ensure consistency. Negotiations between the respective governing bodies were required to fix rules to be used for tours, though generally the other nations took their lead from the British authorities. For example, the field goal was banned by the New South Wales Rugby League in 1922, however this method of scoring was not officially recognised as being removed from the game until 1950, when the British authorities banned it.[19]

This situation endured until 1948, when at the instigation of the French, the Rugby League International Federation (RLIF) was formed at a meeting on 25 January 1948 in Bordeaux. The 1947–48 Northern Rugby Football League season's Challenge Cup Final was the first rugby league match to be televised.[17] All spectator sports in the United Kingdom experienced a surge in interest in the years following the end of World War II and rugby league boomed.[20] Large crowds came to be expected as the norm for a period of around 20 years. The total crowds for the British season hit a record in 1949–50, when over 69.8 million paying customers attended all matches.[21] On Saturday 10 November 1951 the first televised international rugby league match was broadcast from Station Road, Swinton, where Great Britain met New Zealand in the second Test of that 1951 series.

The surge in public interest in the sport was further demonstrated by the 1954 Challenge Cup Final Replay between Halifax and Warrington, held at Odsal Stadium, Bradford on Wednesday, 5 May 1954. The officially recorded attendance was at 102,569 (a record for a single match of rugby league that stood until 107,999 watched Melbourne Storm defeat St George Illawarra Dragons at Stadium Australia in 1999). It is estimated that a further 20,000 spectators were present, as many got in free after a section of fencing collapsed. Warrington beat Halifax 8–4.

This period also saw growth in crowds in Australia, New Zealand and France. This was a golden age for the French, who led by the incomparable Puig Aubert, travelled to Australia and defeated their host in a three test series in 1951. On their return to France the victorious team were greeted by an estimated 100,000 fans in Marseille. They repeated the feat in France 1952–53 and again in Australia in 1955.

Birth of the World Cup

The French were the driving force behind the staging of the first Rugby League World Cup (also the first tournament to be officially known as the "Rugby World Cup") in 1954. This competition has been held intermittently since then, in a variety of formats. Unlike many other sports the World Cup has never really been the pinnacle of the international game, that honour falling to international test series such as the Ashes.

In 1956, the state government of New South Wales legalised the playing of poker machines ("pokies") in profit clubs, and this rapidly became the major source of income for NSW "leagues clubs", some of which became palatial "homes away from home" for their supporters. The pokie windfall stemmed the steady trickle of Australian players to the better-financed clubs in England, and led to increased recruiting of rugby union and league players from Queensland and overseas by New South Welsh clubs. Within the space of several years, the Sydney-based league had come to dominate the code within Australia. The large profits accrued from gambling have always been controversial; many questioned the morality of such an income stream and felt that it would inevitably lead to financial turmoil and scandal.

1961 saw the first televised game of rugby league in Australia.[22] In the UK live coverage of professional rugby league began in the early 1960s, exposing the game to a national audience.[23] David Attenborough, then controller of BBC2, made the decision to screen rugby league games from a new competition specially designed for evening televising, the BBC2 Television Floodlit Trophy. Although it was widely seen as a gimmick, it proved a success, and rugby league has featured on television ever since, to the point where (like most sports) income from selling broadcasting rights is the single greatest source of revenue for the game. In Australia the 1967 NSWRFL season's grand final became the first football grand final of any code to be televised live in Australia. The Nine Network had paid $5,000 for the broadcasting rights.[24]

This period also saw further alterations to the rules of the sport. In 1964 substitutes were allowed for the first time, but only for players injured before half-time. In 1966 limited tackles were introduced. In 1967 professional matches were first allowed on Sundays. Also this year the number of times a team could retain possession after a play-the-ball was limited to four tackles.[25] The concept of limited tackles had existed in American football since the 1880s, and it was hoped that this would encourage more attacking play, and prevent teams from simply playing to maintain possession of the ball at all costs. Although successful in this respect, it was felt that four tackles did not give sufficient time to develop an attack, with play often being characterised by pure panic. In 1971, the number of tackles allowed was increased to six, and has remained so ever since. That year the value of field goals was reduced as well, from 2 to 1.[25]

In Britain's 1971–72 season, sponsors first entered the game: brewers Joshua Tetley and cigarette brand John Player. In 1976 Sydney club Eastern Suburbs set a precedent with a major sponsor, City Ford appearing on their jersey.

In 1977 Australian forward Graham Olling made headlines when he became the first rugby league player to admit to taking anabolic steroids, which at the time were not illegal in the sport.[26]

In 1980 the first State of Origin match was played in Australia. This pitted teams representative of Queensland and New South Wales against each other. Although matches between the two had taken place for many years, the origin concept (borrowed from Australian rules football) meant that for the first time players were selected based on where they first played the game, rather than where they were currently playing. This had an immediate effect, evening up the competition, which had come to be dominated by New South Wales because of the financial strength of the Sydney clubs, and rousing greater pride in spectators as their players were considered more truly representative of their respective states. State of Origin matches are now some of the biggest and most keenly fought contests in Australian sport.

The 1980s also saw attempts to improve rugby league's popularity outside its traditional geographical boundaries. In Great Britain a new team from London (Fulham) was admitted to the professional ranks. In Australia, the first sides from outside the Sydney metropolitan area entered the top-flight competition in. In 1982 the Illawarra Steelers (based in Wollongong) and the Canberra Raiders (based in the national capital, Canberra) entered the competition. As a result of a lucrative illegal betting market having developed since the Second World War, FootyTAB was founded in 1983 to develop legal betting on rugby league, and was a resounding success.

In 1981 the 'Sin Bin' rule was introduced in rugby league in Australia. Newtown hooker Barry Jensen became the first player sent there. In 1983 the number of points awarded for scoring a try increased from three to four. Also in 1983, the Australian ABC-TV current affairs programme Four Corners, aired an episode entitled "The Big League". The programme was to have repercussions throughout Australian sport, and in the wider community. Reporter Chris Masters (the brother of league identity Roy Masters) described allegations of corruption within the NSWRL, including suggestions that officials were siphoning funds from particular clubs and international matches while players and spectators endured sub-standard facilities. As a result of the programme, a Royal Commission (the Street Royal Commission) was called. It led to the New South Wales chief magistrate Murray Farquhar being jailed, the end of NSWRL president Kevin Humphreys' career and the ABC being sued for libel by NSW State Premier, Neville Wran (who eventually settled out of court). Masters, Four Corners and the commission are widely credited with widespread improvements in the administration of rugby league in Australia.

In the late 1980s, rugby league competitions were launched or continued to expand in Russia, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands.

A further expansion to the NSWRL in 1988 saw the first Queensland teams added to the league: Brisbane Broncos and Gold Coast Giants, as well as another team from outside Sydney, Newcastle Knights. Expansion occurred again in 1995, with the addition to the League of teams from Perth, Townsville and Auckland.

"Thirteen-man rugby league has shown itself to be a faster, more open game of better athletes than the other code. Rugby union is trying to negotiate its own escape from amateurism, with some officials admitting that the game is too slow, the laws too convoluted to attract a larger TV following."

In 1995 Ian Roberts became the first high-profile Australian sports person and first rugby footballer in the world to come out to the public as gay.[28]

The 1990s saw the importance of television income to the sport continue to rise, and a battle for control of television rights led to the infamous Super League war, which saw the game split between rival competitions. This event affected the sport across the world during the middle of decade, and the damage done is only now being undone.

Switch to Summer Rugby and World Cup Expansion

While the Super League war was being fought in Australia, Rupert Murdoch approached the English clubs with a view to forming a Super League, primarily as a way to gain the upper hand during his battle with Kerry Packer for broadcasting rights for the sport in Australia. A large sum of money from News Corporation's UK subsidiary, BSkyB, helped fund the proposal. The new competition got under way in 1996. As part of the deal, rugby league switched from a winter to a summer season. The British, Australian and New Zealand seasons are now played concurrently from March to October, and major international tournaments are now largely played in November. The French, however, have continued to play a winter season.

After the 1997 season in Australia the Super League war came to an end, with News International and the Australian Rugby League agreeing to merge their competitions to create the National Rugby League, which commenced in 1998. The first ever team from Victoria, the Melbourne Storm entered the competition. Several clubs were either forced to merge (e.g. St. George Dragons and Illawarra Steelers became St George Illawarra Dragons), or folded. The omission of South Sydney Rabbitohs, one of the founding members of the original NSWRL, led to mass protests. Although Souths did not participate in the NRL during 2000 and 2001, a Federal Court decision in July 2001 paved the way for them to return to the league in 2002.

In 1995, rugby union went professional, and those who had long derided rugby league as merely a professional version of that game were soon predicting the demise of the sport. The Super League war, the financial problems of the 2000 Rugby League World Cup and the signing of several high-profile rugby league stars by the union game gave ammunition to this claim.

With the professionalism of rugby union, several high-profile league players changed codes, with varying degrees of success. Australian RU administrators appeared to be targeting league internationals when in 2001/02 Kangaroos Wendell Sailor, Mat Rogers and Lote Tuqiri all switched and soon represented the Wallabies. Other high-profile players, such as Jason Robinson, Iestyn Harris and Henry Paul followed. However press claims at the time that the "flood-gates" had opened proved to be more sensational than portentous. By the end of the decade, the flow of league players moving on big-money contracts to union seemed to have stabilised, and in fact in many cases this actually proved to be positive for rugby league, with the money gained from transfer fees being used to fund expansion and additional youth development in Britain and with many of the star crossover players returning to rugby league in Australia.

The game needs to be aware of it and take steps to ensure that it doesn't become a flood. We need to ensure we can pay our senior players as much as we can and we need to make sure our international football is up to scratch.

— Australian national coach Chris Anderson following the news of Wendell Sailor becoming the first current Australian test player to be lured to rugby union in 2001.[29]

In Britain, the ending of discrimination against rugby league resulting from professionalism in rugby union led to an increase in numbers in the amateur game, with many rugby union amateurs keen to try out the other code. In 2004 the Rugby Football League was able to report a return to profitability, a reunified structure and a 94% increase in registered players in just two years.[30]

In 2008, rugby league held its first World Cup since the disastrous 2000 tournament. The 2008 competition was heralded as a great success, turning a significant profit, and was generally seen as a major step forwards in the development of the international game. In addition, the Rugby League European Federation was set up during the decade and as a result the game saw massive advances in both the quality and quantity of international competition. The game in France saw a renaissance, largely as a result of the Catalans Dragons entry into Super League, while large advances were made in other countries such as Wales and New Zealand, who finished the decade as world champions.

In Australia in 2009, rugby league's popularity was confirmed as it had the highest official television ratings figures of any sporting event.[31]

The 2013 Rugby League World Cup was held in Europe, with the final played at England's Old Trafford in front of 74,468, the largest crowd to attend an international fixture.[32]

The 2014 National Rugby League Grand Final was the highest rated television show for the year in Australia.[33]

In 2015, the league went through a structure change with promotion and relegation reintroduced between Super League and the Championship. It also saw rugby league pull 4 of the top 5 highest rated television broadcasts in Australia.[34]

In 2017 rugby league saw its first professional club outside of Europe or Australasia/Oceania when the Canadian side Toronto Wolfpack entered the British Rugby League system in the third division. Toronto won League One in their first season and won promotion to the Championship, the second tier of British Rugby League for 2018. As of October 2018, Toronto's owner stated his intention of setting up a new franchise in Canada, whilst a New York City based team expressed their interest to join Toronto in the British rugby league system.

See also

- Rugby league

- History of rugby union

- Tom Brock Lecture – an annual lecture celebrating the history of rugby league in Australia

- Super League war

- Rugby league in Australia

- Rugby league in New Zealand

- List of defunct rugby league clubs

References

- "Early Days". A History of Bradford City Football Club. bantamspast.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Frost. Bradford City A Complete Record 1903–1988. p. 11.

- Fagan, Sean (2008). League of Legends: 100 Years of Rugby League in Australia. National Museum of Australia. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-876944-64-3.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "- Huddersfield Rugby League Heritage". Huddersfieldrlheritage.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- BBC. "Rugby League's leading man". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- "Our Door Sports". Observer. 26 October 1895. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- Baker, Andrew (20 August 1995). "100 years of rugby league: From the great divide to the Super era". Independent, The. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Collins, Tony. "'Where's George?': League's Forgotten Feature Film". Rugby Reloaded. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Nauright, John & Charles Parrish (2010). Sports around the World. USA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843019.

- "Outside Chat". NZ Truth, Issue 170. New Zealand. 19 September 1908. p. 3. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- "Why they lost the first three games in australia". The Evening Post. Vol. LXXVII, no. 145. 12 June 1909. p. 3. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- "Kangaroos v. Wallabies". West Coast Times. New Zealand. 6 September 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- Ward, Tony (2010). Sport in Australian national identity. UK: Routledge. ISBN 9781317987659.

- Pramberg, Bernie (2 May 2009). "Leo Donovan special guest at BRL celebrations". The Courier-Mail. Australia: Queensland Newspapers. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- "Football". The Sydney Mail. Australia. 13 August 1910. p. 54. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- "The History of Rugby League". Rugby League Information. napit.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Lyle, Beaton (7 April 2009). "75 Years of French Rugby League". rleague.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "The Development of British Rugby League". Wakefieldtrinity-programmes.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Demsteader, Christine (1 October 2000). "Rugby League's home from home". BBC Sport. UK: BBC. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Jon Henderson (2007). Best of British: Hendo's sporting heroes. UK: Yellow Jersey Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780224082488.

- Sean Fagan. "nrl.com". History of Rugby League. NRL. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- Eric Dunning, Kenneth Sheard (2005). Barbarians, Gentlemen And Players: A Sociological Study Of The Development Of Rugby Football. UK: Routledge. p. 194. ISBN 9780714682907.

- Masters, Roy (4 October 2009). "Messenger can watch a better league broadcast in the US than south of the border". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Middleton, David (2008). League of Legends: 100 Years of Rugby League in Australia (PDF). National Museum of Australia. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-876944-64-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2011.

- Curtin, Jennie (11 July 1998). "Simply the Best". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Ian, Thomsen (28 October 1995). "Australia Faces England at Wembley : A Final of Rugby Favorites". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Peter, O'Shea (3 October 1995). "Out of the field". The Advocate. Here Publishing. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- news.bbc.co.uk (7 February 2001). "Aussie coach warns rugby league bosses". BBC Sport Online. BBC. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- "Participation in rugby league booms". Rfl.uk.com. 2 August 2004. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005.

- Newstalk ZB (21 December 2009). "League becomes Australia's top sport". TVNZ. New Zealand: Television New Zealand Limited. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- Fletcher, Paul (1 December 2013). "Rugby League World Cup 2013: A joy that must not be wasted". BBC News. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Colin Vickery (12 November 2014). "Revealed: 2014's top TV shows". News.com.au. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Rawsthorne, Sally (28 November 2015). "Winners and losers in TV ratings war". Dailytelegraph.com.au. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Fagan, Sean (2005). The Rugby Rebellion – The Divide of League and Union. ISBN 978-0-9875002-7-4

- Gate, Robert (1989). Illustrated History of Rugby League. Arthur Barker. ISBN 0-213-16970-3

- Heads, Ian (25 August 2002). The Dogs qualify for my top eight.... The Sun-Herald

Further reading

- Ian Collis, Alan Whiticker (2007). One hundred years of Rugby League. Australia: New Holland.

- Collins, Tony (1998). Rugby's Great Split: Class, Culture and the Origins of Rugby League Football. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39617-4.

- Collins, Tony (2006). Rugby League in Twentieth Century Britain: A Social and Cultural History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39615-8.

- Delaney, Trevor (1984). The Roots of Rugby League. T.R. Delaney. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-9509982-0-6.

- Delaney, Trevor (1993). Rugby Disunion: A Two-part History of the Formation of the Northern Union: Volume 1: Broken-time. T.R. Delaney. p. 152. ISBN 0-9509982-3-0. OL 15344746M.

- Dunning, Eric; Kenneth Sheard (1979). Barbarians, Gentlemen and Players. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 336. ISBN 0-85520-168-1.

- Gate, Robert (1986). Gone North: Welshmen in Rugby League: volume 1. R.E. Gate. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-9511190-0-6.

- Gate, Robert (1989). Rugby League: an illustrated history. Arthur Barker. p. 160. ISBN 0-213-16970-3.

- Ian Heads & David Middleton (2008). A centenary of Rugby League 1908–2008: the definitive story of the game in Australia. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-3830-0.

- Macklin, Keith (1974). The history of Rugby League football. Paul. ISBN 0-09-120780-0.

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey (1990). At the George and Other Essays on Rugby League. Sceptre. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-340-53038-2.

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey (1995). A people's game: the centenary history of rugby league football, 1895–1995. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-62834-0.

External links

- History of Rugby League at NRL.com

- A brief history of rugby league at St. George Dragons website

- The Great Schism at RugbyFootballHistory.com

- Rugby League History and Heritage at The RFL.com

- Rugby League History at rlheritage.co.uk (Archive, 10 February 2011)

- Rugby League from the Hardman Era – Era Of The Biff