History of the National Hockey League (1967–1992)

The expansion era of the National Hockey League (NHL) began when six new teams were added for the 1967–68 season, ending the Original Six era. The six existing teams were grouped into the newly created East Division, and the expansion teams—the Los Angeles Kings, Minnesota North Stars, Oakland Seals, Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins and St. Louis Blues—formed the West Division.

The NHL added another six teams by 1974 to bring the league to 18 teams. This continued expansion was partially brought about by the creation of the World Hockey Association (WHA), which operated from 1972 until 1979 and sought to compete with the NHL for markets and players. Bobby Hull was the most famous player to defect to the rival league, signing a $2.75 million contract with the Winnipeg Jets. When the WHA ceased operations in 1979, the NHL absorbed four of the league's teams—the Edmonton Oilers, Hartford Whalers, Quebec Nordiques and Winnipeg Jets. This brought the NHL to 21 teams (the Cleveland Barons had ceased operations in 1978), a figure that remained constant until the San Jose Sharks joined as an expansion franchise in 1991.

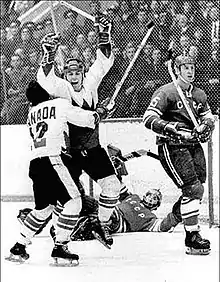

The NHL became involved in international play, starting with the Summit Series in 1972, which pitted the top Canadian players of the NHL against the top players of the Soviet Union. Canada won the eight-game series four wins to three with one tie. The success of the series led to the creation of the Canada Cup, held five times between 1976 and 1991. NHL teams also faced Soviet League teams that toured North America between 1975 and 1991 in what was known as the Super Series. The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 saw many former Soviet-Bloc players stream into the NHL, joining several players who had defected in the 1980s.

This was the highest scoring period in NHL history. It was led in the 1980s by the Edmonton Oilers and Wayne Gretzky, who scored 200 points or more four times, including a current league-record 215 in 1985–86. Gretzky's 92 goals in 1981–82 also remains a league record. No other player in NHL history has scored 200 points, although Mario Lemieux came close in 1988–89 with 199.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the NHL |

|---|

|

| National Hockey League |

|

|

Background

Expansion had been a major topic of discussion among NHL owners since 1963, when William M. Jennings of the New York Rangers proposed adding two new teams on the West Coast to counter fears that the Western Hockey League intended to compete as a major league.[1] After several years of discussion, the NHL announced in February 1966 that it would expand by six teams, doubling the league's size. The Los Angeles Kings, Minnesota North Stars, California Seals, Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins and St. Louis Blues began play in the 1967–68 season.[2] They formed the newly created West Division, and the existing teams were grouped into the East Division. The playoff format was constructed so that an established team would face an expansion team in the Stanley Cup Finals.[3] The Clarence S. Campbell Bowl was created in honour of league president Clarence Campbell, and was awarded to the West Division champion.[4]

The new teams were stocked by the NHL's first expansion draft, as each team selected 20 players from the existing franchises. There was much debate over how many players each existing team could protect: the strongest clubs wished to protect more players, while the weaker clubs hoped that protecting fewer players would help improve the balance of competition. Montreal Canadiens manager Sam Pollock's suggestion to allow each team to protect eleven players to start, then add an additional player to their protected list for each player selected in the draft, was ultimately agreed to as a compromise solution.[1] In addition, an "intra-league draft" was held following the 1968 and 1969 seasons to help accelerate the improvement of the expansion teams. Each team protected two goaltenders and fourteen skaters, leaving their remaining players open to be selected by any other team.[5]

Some teams created instant farm systems by buying existing minor league franchises. The Kings bought the Springfield Indians of the American Hockey League the night before the expansion draft, leading the Flyers to purchase the Quebec Aces.[6] Expansion also changed how the amateur draft was handled. The old system, in which franchises sponsored junior teams and players, was abandoned by 1969 when all junior-aged players were made eligible for the entry draft.[3]

Expansion years

In their inaugural season, the Flyers finished atop the West Division, recording 73 points in 74 games.[7] The California Seals, a pre-season favourite to win the division, changed their name to the Oakland Seals a month into the season. The team disappointed both on the ice and at the gate, finishing last in the NHL with 14 wins.[8] The Blues defeated the Flyers and North Stars to become the first expansion team to play for the Stanley Cup, where they were defeated in four consecutive games by the Canadiens.[7] The Blues reached the finals again in both 1969 and 1970, but were similarly swept in both years, losing to the Canadiens and Boston Bruins, respectively.[9]

On January 13, 1968, North Stars' rookie Bill Masterton became the first and, to date, only player to die as a result of injuries suffered during an NHL game.[10] Early in a game against the Seals, Masterton was checked hard by two players, Ron Harris and Larry Cahan, causing him to flip over backwards and land on his head.[11] He was rushed to hospital with massive head injuries, and died there two days later.[12] The National Hockey League Writers Association presented the league with the Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy later in the season; the trophy is awarded annually to the player who best exemplifies the qualities of perseverance, sportsmanship and dedication to hockey.[7] Following Masterton's death, players slowly began wearing helmets; starting in the 1979–80 season, the league mandated that all players entering the league wear them.[10]

Bobby Orr

.jpg.webp)

In the 1968–69 season, second-year defenceman Bobby Orr scored 21 goals, an NHL record for a defenceman, en route to winning his first of eight consecutive Norris Trophies as the league's top defenceman.[13] At the same time, Orr's teammate, Phil Esposito, became the first player in league history to score 100 points in a season, finishing with 126 points. He was one of three players to break the century mark that year, including Bobby Hull and 41-year-old Gordie Howe.[14]

A gifted scorer, Orr revolutionized defencemen's impact on the offensive side of the game, as blue-liners began to be judged on how well they created goals in addition to how well they prevented them.[15] Orr scored the Stanley-Cup-winning goal in overtime of the fourth game against the Blues in 1970, which gave the Bruins their first championship in 29 years. The goal was highlighted by his famous flight through the air after being tripped up following his shot.[16] Orr twice won the Art Ross Trophy as the NHL's leading scorer, still the only defenceman in NHL history to do so. His plus/minus of +124 in 1970–71 is a league record.[17] Orr signed a five-year contract that paid him $200,000 per season in 1971, the first $1 million contract in league history.[16]

Chronic knee problems plagued Orr throughout his career. In 1972, he tore ligaments in his left knee after a hard hit, leading to the first of six knee operations.[13] He played 12 seasons in the NHL before injuries forced his retirement in 1978. Orr finished with 270 goals and 915 points in 657 games and won the Hart Memorial Trophy as the league's Most Valuable Player three times.[13] The customary three-year post-retirement waiting period for entry into the Hockey Hall of Fame was waived as he was enshrined in 1979.[16]

Buffalo and Vancouver

In Canada, there was widespread outrage over the denial of an expansion team to Vancouver in 1967.[18] Three years later, the NHL added a third Canadian team (and the first in Western Canada) when the Vancouver Canucks, formerly of the Western Hockey League, were admitted as an expansion team for the 1970–71 season, along with the Buffalo Sabres, another team whose owners had bid unsuccessfully for an expansion team in 1967.[19] The Canucks were placed in the East Division, despite being on the west coast, while the Chicago Black Hawks were shifted to the West in an attempt to equalize the divisions' strength.[20]

The league also gave the Sabres and Canucks the first two picks in each round of the 1970 NHL Amateur Draft, offering them a better opportunity to build their rosters than the 1967 expansion teams had.[20] Buffalo's first round pick was Gilbert Perreault, a future Hall of Famer who would play seventeen seasons in Buffalo.

Before the 1971–72 season, Gordie Howe and Jean Beliveau announced their retirements. Beliveau finished his 18-year career with 10 Stanley Cups, 2 Hart Trophies and 1,219 career points; his points total was the second-highest in NHL history. After playing 25 seasons in the NHL, Howe retired as the league's all-time leader in games played, goals, assists and points.[21] Howe was a six-time league scoring champion, and also won six Hart Trophies.[22] Both players had the customary three-year waiting period waived for entry into the Hockey Hall of Fame in acknowledgement of their achievements.[23]

World Hockey Association

In 1972, the NHL faced competition from the newly formed World Hockey Association (WHA). The WHA lured many players away from the NHL, including Derek Sanderson, J. C. Tremblay and Ted Green.[24] The WHA's biggest coup was to lure Bobby Hull from the Black Hawks to play for the Winnipeg Jets. Hull signed a 10-year deal: five years as a player for $250,000 per season, and five more for $100,000 per season in a front-office position. It also included a $1 million signing bonus. The deal totaled $2.7 million, and lent instant credibility to the new league.[25] After Hull signed, several other players quickly followed suit. Bernie Parent, Gerry Cheevers, Johnny McKenzie and Rick Ley jumped to the WHA as the NHL suddenly found itself in a war for talent.[26] By the time the 1972–73 WHA season began, 67 players had switched from the NHL to the WHA.[27] Defections continued following the season, and the WHA scored another major coup when it signed Gordie Howe's sons Mark and Marty. The league then convinced Gordie to come out of retirement to play with them on the Houston Aeros.[24]

The NHL tried to block several of the defections. The Bruins attempted to restrain Cheevers and Sanderson from joining the WHA, though a United States federal court refused to prohibit the signings. The Black Hawks were successful in having a restraining order filed against Hull and the Jets pending the outcome of legal action the Black Hawks were taking against the WHA. The WHA was eager for the court action, intending to challenge the legality of the reserve clause, which bound a player to their NHL team until that team released him.[28] In November 1972, a Philadelphia district court placed an injunction against the NHL, preventing it from enforcing the reserve clause and freeing all players who had restraining orders against them, including Hull, to play with their WHA clubs. The decision effectively ended the NHL's monopoly on major league professional hockey talent.[29]

The NHL also found itself competing with the WHA for markets. Initially, the league had no intention to expand past 14 teams, but the threat the WHA posed changed this. Hoping to keep the WHA out of the newly completed Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Uniondale, New York and the Omni Coliseum in Atlanta, Georgia, the league hastily announced the creation of the New York Islanders and Atlanta Flames as 1972 expansion teams.[30] Following the 1972–73 season, the NHL announced it was further expanding to 18 teams for the 1974–75 season, adding the Kansas City Scouts and Washington Capitals,[31] which marked the end of the league's first major expansion period. In just eight years, the NHL had tripled in size to 18 teams.

Summit Series

Internationally, Canada had long been protesting the Soviet Union's use of "professional amateurs" at the World Championships and the Olympic Games, which were amateur events. Canada withdrew from international competition in 1969[34] and boycotted the 1972 Olympic hockey tournament.[35] As an alternative, NHL Players' Association executive director Alan Eagleson negotiated a deal with Soviet authorities to hold an eight-game series between the Soviet national team and Canada's top professionals.[36]

The tournament was the NHL's response to the defection of players to the WHA. Bobby Hull was barred from playing, as was any other player who signed a contract with the rival league, which was a heavily criticized move. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau sent a telegram to NHL president Clarence Campbell, expressing his "intense interest which I share with millions of Canadians ... that Canada should be represented by its best hockey players, including Bobby Hull".[37] Echoing the feelings of the public, Hull called the decision "crazy", and stated that "I'm a Canadian and I want to play for my country. I don't know why the NHL has to be so petty over this. I want to do this for Canada."[37] The NHL did not relent.

"Here's a shot. Henderson made a wild stab for it and fell. Here's another shot. Right in front. They score! Henderson scores for Canada!"

—Foster Hewitt's account of the "goal heard around the world" as Paul Henderson scored the decisive marker in game eight.[38]

The series was tied at three wins apiece and a tie entering the eighth and deciding game, with millions of Canadians watching "the game of the century".[39] With the game tied at five late in the third, the Soviets were met with a concerted Canadian attack in the final seven minutes.[40] With 34 seconds remaining in the game, Esposito took a shot at Vladislav Tretiak from 12 feet out. Paul Henderson scooped up the rebound and put it past the fallen Soviet goalie to score the goal that won the game, 6–5, and the series.[41] Later, Alexander Yakolev, the former Soviet ambassador to Canada, argued that the Summit Series planted the seeds of glasnost and perestroika in the Soviet Union, as it was one of the first times that the Soviet people had seen so many foreigners who had not come to do harm, but to share in the game.[42]

Legacy

The series forced the NHL and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association to reassess all aspects of how the game was played in North America. Journalist Herb Pinder described the NHL to that point in this way: "The Europeans took our game and evolved it, while we stood still or even went backwards. The Russians had a style, and the Czechs' style was different from that ... There was this hockey world evolving through international competition, and we're back here, stuck, just playing ourselves. It was a business monopoly. And like any monopoly, the NHL got stagnant."[43] Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Canadian hockey encouraged the adoption of new coaching and training methods used in Europe, and emphasized conditioning and skills development.[44]

The NHL took a greater interest in international play. The Canada Cup, a tournament that featured the top professional players in the world, was held first in 1976, and then four more times until 1991. It was succeeded by the World Cup of Hockey in 1996. Beginning in 1975, Soviet club teams began touring North America, playing NHL clubs in exhibition games that were known as the Super Series. The Calgary Flames and Washington Capitals similarly toured the Soviet Union in 1989 in the first "Friendship Series". The Soviet national team defeated an NHL all-star team in a 1979 challenge series, two games to one, and split Rendez-vous '87, a two-game series held in Quebec City.[45]

1970s

Broad Street Bullies

The 1970s were associated with aggressive, and often violent, play. Known as the "Broad Street Bullies", the Philadelphia Flyers are the most famous example of this style.[46] The Flyers established league records for penalty minutes—Dave "the Hammer" Schultz's total of 472 in 1974–75 remains a league record[47]—and ended up in courtrooms multiple times when players went into the stands to challenge fans who got involved. One such incident occurred in Vancouver in December 1972, when a fan reached over the glass to pull the hair of Don Saleski, who had a chokehold on Vancouver's Barry Wilkins. Bobby Taylor and several Flyers teammates followed the fan into the stands. The next time Philadelphia went to Vancouver, several players were brought before the courts on charges that ranged from use of obscene language to common assault. Six players were fined, and Taylor received a 30-day suspended sentence.[48] Despite these incidents, the Flyers won: they captured the 1974 Stanley Cup, becoming the first expansion team to win the league championship, and repeated as champions in 1975.[46]

In 1975, Soviet club teams began to tour North America in the first Super Series. The Canadiens played Central Red Army to a 3–3 draw on New Year's Eve 1975, in a game that is considered one of the finest ever played.[49] Red Army lost only one of four games against the NHL in the first tour, a 4–1 defeat to Philadelphia, who intimidated them as the Flyers did to their NHL opponents. At one point, Red Army threatened to forfeit the game after Ed Van Impe decked Valeri Kharlamov. Red Army was persuaded to complete the game after Alan Eagleson threatened to withhold their appearance fee if the team did not return to the ice.[49] Super Series games continued until 1991, when Soviet players were allowed to enter the NHL after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

End of the two-league era

On February 7, 1976, Maple Leafs star Darryl Sittler set an NHL record, scoring 10 points in one game in an 11–4 victory over the Bruins. His six-goal, four-assist effort broke Maurice Richard's record of eight points in a game.[50] The game came shortly after the Bruins lured Gerry Cheevers back from the WHA, though Cheevers was given an extra night to rest, and rookie Dave Reece was the victim of all 11 Toronto goals. It was his 14th, and final, NHL game.[51]

By 1976, both leagues were dealing with serious financial problems. Talks of a merger between the NHL and the WHA were growing. Bobby Hull declared that a merger was "inevitable", though WHA president Bill MacFarland stated that his league had no interest in joining with the NHL.[52] In 1976, for the first time in four decades, the NHL approved franchise relocations; the Scouts moved after just two years in Kansas City to Denver to become the Colorado Rockies, while the California Golden Seals became the Cleveland Barons.[52] In its wake, the league quietly shelved provisional expansion franchises granted to Seattle and Denver to take place in the 1977 season. Two years later, after failed overtures towards merging the Barons with Washington and Vancouver, they merged with the Minnesota North Stars, reducing the NHL to 17 teams for 1978–79.[53]

The WHA's last triumph was to lure junior prodigy Wayne Gretzky to their league in 1978–79. Nelson Skalbania, owner of the Indianapolis Racers and part owner of the Edmonton Oilers, was convinced to sign Gretzky to play for the Racers.[54] The 17-year-old Gretzky scored 110 points in his first professional season, split between the Racers and the Oilers.[55]

The move towards a merger picked up in 1977 when John Ziegler succeeded Campbell as NHL president.[56] After several years of negotiations, WHA owners thought they had an agreement in March 1979. The motion to merge failed when supporters in the NHL lost by one vote.[57] Word got out that the Montreal Canadiens, owned by Molson Brewery, and the Vancouver Canucks, who served Molson products at their games, had voted against the merger. Fans across Canada quickly organized a boycott of Molson products, while the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion urging the NHL to reconsider. Another vote was held, and both Montreal and Vancouver switched their votes, allowing the motion to pass.[58] The WHA folded following the 1978–79 season, and the Edmonton Oilers, New England Whalers, Quebec Nordiques and Winnipeg Jets joined the NHL as expansion teams.[56]

Twenty-one teams

The merger brought Gordie Howe back to the NHL for one final season in 1979–80. At age 51, Howe played all 80 games for the Whalers, scoring 15 goals to bring his NHL career total to 801. He entered his second retirement as the league's all-time scoring leader with 1,850 points.[22] Howe's final season was also the last for the Atlanta Flames. The team averaged an attendance of only 9,800 fans per game and lost over $2 million in 1979–80.[59] They were sold for a record $16 million, and relocated north to become the Calgary Flames in 1980–81.[60] Two years later, the Rockies were sold for $30 million, and left Denver to become the New Jersey Devils for the 1982–83 season.[61]

The St. Louis Blues nearly relocated to Saskatoon in 1983, as Bill Hunter, an original investor in the WHA, announced an intention to purchase and relocate the team. Hunter quickly convinced 18,000 people to commit to season tickets in a proposed arena for the city.[62] The other team owners rejected the sale and relocation by a 15–3 vote, prompting the Blues' owner, Ralston Purina, to file a $60 million anti-trust lawsuit against the league.[63] Both the league as a whole and the individual teams filed $78 million counter suits against Purina.[64] As part of the conflict, Purina turned the team over to the NHL at the beginning of June 1983 to "operate, sell or dispose of in whatever manner the league desires",[65] while the Blues refused to participate in the 1983 NHL Entry Draft, forfeiting all of their draft picks.[66] By the end of July, the league had sold the team to Harry Ornest, who vowed the team would remain in St. Louis.[67] Ralston Purina and the NHL settled their legal issues in 1985, though terms of the settlements were not released.[68]

In 1980, the New York Islanders won their first of four consecutive Stanley Cups.[69] With the likes of Billy Smith, Mike Bossy, Denis Potvin, and Bryan Trottier, the Islanders dominated both the regular season and the playoffs.[70] In 1981, Bossy became the first player to score 50 goals in 50 games since Maurice Richard in 1945.[69] In 1982–83, the Edmonton Oilers won the regular season championship. The Islanders and Oilers met in the Finals and New York swept Edmonton for their last Stanley Cup.[71] They were the second franchise to win four straight championships, after the Canadiens.[69] The 1984 playoffs would be the site of the infamous Good Friday Massacre between the Quebec Nordiques and the Montreal Canadiens.

The following season, the Oilers and Islanders met again in the playoffs. The Oilers won the rematch in five games, marking the start of another dynasty.[72] Led by Wayne Gretzky and Mark Messier, the Oilers won five Stanley Cup championships between 1984 and 1990. The Oilers won two consecutive Cups in the 1983–84 and 1984–85 seasons, and in the 1986–87 and 1987–88 seasons. They also won a Cup in the 1989–90 season.[73] The Oilers' Cup streaks were interrupted in the 1985–86 and 1988–89 seasons by two other Canadian teams. Edmonton's hopes for a third consecutive title in 1986 were dashed by their provincial rival, the Calgary Flames, after Oilers' rookie Steve Smith accidentally bounced the series-winning goal off goaltender Grant Fuhr and into his own net.[74] Smith's error remains one of the most legendary blunders in hockey history.[75][76][77] The Flames were defeated by the Canadiens in the finals, as rookie goaltender Patrick Roy led Montreal to their 23rd Stanley Cup.[78] The 1989 final was a rematch between the Flames and the Canadiens and was won by Calgary, which captured its only championship in franchise history.[79] The Flames also became the only team to defeat the Montreal Canadiens for the Stanley Cup at the Montreal Forum. The league would move its headquarters from Montreal to New York City in 1989.[80]

The 21-team era ended in 1990, when the league revealed ambitious plans to double league revenues from $400 million within a decade and bring the NHL to 28 franchises during that period.[81] The NHL quickly announced three new teams: the San Jose Sharks, who began play in the 1991–92 season, and the Ottawa Senators and Tampa Bay Lightning, who followed a year later.[82]

The Sharks' creation forestalled a unilateral franchise move by North Stars owners George and Gordon Gund to the San Francisco Bay Area. A settlement with the league granted them the expansion franchise, while they sold the North Stars to Howard Baldwin's group in 1990. Prior to the 1991–92 season, the Sharks and North Stars participated in a unique expansion draft, which saw San Jose select unprotected players from Minnesota (including future All-Star goalie Arturs Irbe) before both teams picked players from the remainder of the league. The Sharks would struggle in their inaugural season, finishing with a league-low 17 wins and 39 points while playing out of the Cow Palace, while the North Stars (who were sold again, to Norman Green, during the 1990–91 season) would make the playoffs for what proved to be the final time before their eventual relocation to Dallas in 1993.

Wayne Gretzky

In the latter part of the 1980s, the Oilers won five Stanley Cup titles in seven years, becoming the only team to score 400 or more goals in a season, which they did four times. With future Hall of Famers Grant Fuhr, Paul Coffey, Jari Kurri, Mark Messier, and Glenn Anderson, they established numerous new scoring records.

The Oilers were led by Wayne Gretzky, who remained with the Oilers when they joined the NHL in 1979. At 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m) and 170 pounds (77 kg), some observers doubted that Gretzky could match his offensive performance from his lone WHA season. "I heard a lot of talk then that I'd never get 110 points like I did in the WHA," said Gretzky.[83] He proved his critics wrong, scoring 137 points in 1979–80 and winning the first of nine Hart Trophies (including 8 consecutive awards from 1980 to 1988) as the NHL's most valuable player.[83] Over the next several seasons, Gretzky established new highs in goals scored in a season, with 92 in the 1981–82 season; in assists, with 163 in the 1985–86; and in total points, with 215 in 1985–86.[84] He also scored 50 goals in 39 games, the fastest any player had reached the total in a single season.[55] Gretzky scored his 1,000th NHL point in his 424th game, breaking Guy Lafleur's old record of 720 games.[85]

Gretzky's teammates set records of their own. Fuhr's 14 assists in the 1983–84 season set a record for most points by a goaltender in a season. In 1985–86, Coffey set a record for the most goals in a season by a defenceman, with 48. Adding 90 assists, Coffey wound up a point short of tying Bobby Orr's record for most points in a season by a blue-liner.[84]

On August 9, 1988, Oilers owner Peter Pocklington, in financial trouble, traded Gretzky, along with Marty McSorley and Mike Krushelnyski, to the Los Angeles Kings in exchange for Jimmy Carson, Martin Gelinas, US$15 million and three first-round draft picks.[86] Gretzky left Edmonton with a tear-filled news conference, and later said that Edmonton was the only place he ever dreaded playing.[87] Gretzky's trade to the Kings popularized ice hockey in the United States, making hockey "cool" in Hollywood, and shocked fans across Canada.[88] The Kings were the most popular Los Angeles sports team, and Gretzky's fame rivaled that of his peers with baseball's Los Angeles Dodgers and basketball's Los Angeles Lakers.[87]

With the Kings, Gretzky broke Gordie Howe's record for career points. On October 15, 1989, against his former Oilers' teammates, and with Howe in attendance, Gretzky tied the record with a first period assist before notching his 1,851st career point with a third period goal. "An award such as this takes a lot of teamwork and help and both teams here today definitely have a part of the 1,851 [points]." said Gretzky.[89]

Fall of the Iron Curtain

While European-born players were a part of the NHL since its founding, it was still rare to see them in the league until 1980.[90] The WHA turned to the previously overlooked European market in search for talent, signing players from Finland and Sweden. Anders Hedberg, Lars-Erik Sjoberg and Ulf Nilsson signed with the Jets in 1974 and thrived in North America, both in the WHA and later the NHL.[91] The Jets won three of the six remaining WHA championships after signing European players, and their success sparked similar signings league-wide.

Borje Salming was the first European star in the NHL. He signed with the Maple Leafs in 1973, and played 16 seasons in the NHL, retiring in 1990. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1996.[90] His fellow Swede, Pelle Lindbergh, was one of the top goaltenders in the world in the early 1980s. He led the Flyers to the 1985 Stanley Cup Finals before dying in a car accident during the 1985–86 season.[92] Finns Jari Kurri and Esa Tikkanen helped lead the Oilers dynasty of the 1980s.[85]

While the WHA opened the door, and players slowly joined the NHL, those behind the Iron Curtain were restricted from following suit. In 1980, Peter Stastny, his wife, and his brother Anton secretly fled Czechoslovakia with the aid of Nordiques owner Marcel Aubut. The Stastnys' defection made international headlines, and contributed to the first wave of Eastern Europeans' entrance into the NHL.[90] Hoping that they would one day be permitted to play in the NHL, teams drafted Soviet players in the 1980s, 27 in all by the 1988 draft.[93] However, defection was the only way such players could join the teams that drafted them. Michal Pivonka defected from Czechoslovakia in 1986, while Russian Alexander Mogilny defected following the 1989 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships in Anchorage, Alaska.[92] Czech teenager Petr Nedved walked into a Calgary police station in January 1989 after playing in the Mac's AAA midget hockey tournament.[94]

Shortly before the end of the 1988–89 regular season, Flames general manager Cliff Fletcher announced that he had reached an agreement with Soviet authorities that allowed Sergei Pryakhin to play in North America. It was the first time a member of the Soviet national team was permitted to play for a non-Soviet team.[95] Shortly after, Soviet players began to flood into the NHL. Teams anticipated that there would be an influx of Soviet players in the 1990s, as 18 Soviets were selected in the 1989 NHL Entry Draft.[93] The entire "KLM" line, the Soviet team's top line, joined the NHL in 1989 as Vladimir Krutov and Igor Larionov played for the Canucks, while Sergei Makarov went to Calgary.[96] Makarov won the Calder Memorial Trophy as rookie of the year in 1990, a selection that caused controversy; he was 32 years old and had played 11 pro seasons in the Soviet League. In the wake of the controversy, the NHL amended its rules: players over the age of 26 were no longer considered for the award.[97] The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the demise of the Iron Curtain paved the way for more Eastern European players to play in North America. Only six European players were selected at the 1979 NHL Entry Draft. That number increased to 32 in 1989, while a record 123 Europeans were drafted in 2000.[98] Europeans made up 22.5% of the NHL in 2013–14, totalling 232 players.[99]

Rules and innovations

The early 1980s saw many tie games. The 1982–83 North Stars and Capitals both finished with 16 ties in 80 games, while 17 of 21 teams tied 10 or more games. The season before, the North Stars recorded 20 ties. As a result of the frequent ties, the NHL reintroduced overtime for the 1983–84 season. The effect was immediate, as only seven teams had ten or more ties. Before its discontinuation during World War II, the NHL played a full 10-minute overtime period. The modern overtime format was set as a five-minute, sudden death period; the game ended when either team scored.[89]

The NHL changed its divisional alignment and playoff formats numerous times as it grew. The league's doubling in 1967 also led to the expansion of the playoffs to eight teams from four the previous year.[100] Expansion to 18 teams in 1974 caused the league to realign into two conferences and four divisions, each named after important figures in league history. The teams were split into the Campbell Conference, consisting of the Patrick and Smythe divisions, and the Prince of Wales Conference, consisting of the Adams and Norris divisions. The playoffs were expanded to 12 teams, and each division winner was granted a bye in the first round of the playoffs.[101] The addition of the four WHA teams in 1979 saw the playoffs expanded to 16 teams.[102]

In 1981, the league realigned all teams by geography, although the historical names of the divisions remained. Eastern teams played in the Adams and Patrick divisions of the Wales Conference, and Western teams played in the Norris and Smythe divisions of the Campbell Conference. In addition, the playoff format was changed to have the top four teams in each division qualify rather than the top 16 teams overall. The first two playoff rounds were played entirely within each division. This format lasted until 1993.[103]

Entry Draft

During the late 1960s, the concept of sponsoring junior players and teams had been dismantled, meaning that for the 1969 NHL Amateur Draft, every player aged 20 or above was eligible to be selected. The Montreal Canadiens, however, exercised a special "cultural option" that allowed them to select two players of French-Canadian heritage, before any other players were selected. These players counted as Montreal's first two choices. After the Canadiens took Rejean Houle and Marc Tardif, the rest of the league voted to end the rule in 1970, just before future star Gilbert Perreault was selected first in the 1970 expansion draft by the Buffalo Sabres.[104]

In 1974, Sabres general manager Punch Imlach decided to play a joke on the league during the draft. He selected Taro Tsujimoto of the "Tokyo Katanas" with his 11th round pick. Other teams were shocked that the Sabres had scouted for players in Japan, and the league made the pick official. Weeks later, Imlach admitted that he made the player up, choosing the name out of a phone book.[104]

The league reformatted the Amateur Draft into the NHL Entry Draft in 1979 and simultaneously lowered the draft age to 19.[105] It was first opened to the public in 1980, when 2,500 fans attended the draft in the Montreal Forum. The public draft has grown such that it is now held annually in NHL arenas and televised internationally.[104]

Timeline

.PNG.webp)

Notes

- The year given refers to the year in which that season began and not the year in which the Stanley Cup Playoffs took place

- The California Golden Seals were known as the California Seals in 1967 and as the Oakland Seals from 1967 to 1970.

- The Cleveland Barons merged with the Minnesota North Stars in 1978.

- "SC" denotes teams that won the Stanley Cup.

See also

References

- Diamond 1991, p. 174

- Pincus 2006, p. 113

- Diamond & Zweig 2003, p. xii

- Clarence S. Campbell Bowl, National Hockey League, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Diamond 1991, p. 183

- Diamond 1991, p. 184

- Diamond 1991, pp. 185–186

- McFarlane 1990, p. 94

- Pincus 2006, pp. 118–119

- Pincus 2006, p. 123

- McFarlane 1990, p. 96

- Players—Bill Masterton, Hockey Hall of Fame, archived from the original on December 4, 2007, retrieved August 9, 2008

- Pincus 2006, pp. 120–121

- Pincus 2006, p. 128

- McCown 2007, p. 195

- The Legends—Bobby Orr, Hockey Hall of Fame, retrieved August 9, 2008

- McFarlane 2004, p. 122

- McKinley 2006, pp. 194–195

- McFarlane 1990, pp. 106–107

- Diamond 1991, p. 199

- McFarlane 1990, p. 109

- The Legends—Gordie Howe, Hockey Hall of Fame, archived from the original on May 13, 2007, retrieved August 9, 2008

- Diamond 1991, p. 204

- Pincus 2006, p. 139

- Willes 2004, p. 33

- McFarlane 1990, p. 112

- McFarlane 1990, p. 113

- McFarlane 1990, p. 132

- McFarlane 1990, p. 133

- Boer 2006, p. 13

- McFarlane 1990, p. 115

- Photographer who captured Henderson's winning goal dead at 79, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, August 22, 2006, retrieved November 21, 2009

- Staples, David (July 28, 2008), "What is the greatest hockey photograph of all time?", Edmonton Journal, retrieved November 21, 2009

- Diamond 1991, p. 206

- Merron, Jeff (February 14, 2002), Russians regroup on other side of the red line, ESPN, retrieved August 29, 2008

- Pincus 2006, pp. 132–133

- McKinley 2006, p. 207

- The Goal Heard Around the World, Hockey Hall of Fame, archived from the original on September 30, 2007, retrieved August 29, 2008

- McKinley 2006, p. 222

- Diamond 1991, p. 208

- McKinley 2006, p. 224

- McKinley 2006, p. 225

- MacSkimming 1996, p. 247

- MacSkimming 1996, p. 245

- MacSkimming 1996, p. 248

- Pincus 2006, p. 134

- Pincus 2006, p. 135

- Diamond 1991, p. 221

- Diamond 1991, p. 231

- The Legends—Darryl Sittler, Hockey Hall of Fame, retrieved August 29, 2008

- Pincus 2006, p. 142

- McFarlane 1990, p. 144

- McFarlane 1990, p. 163

- Willes 2004, p. 219

- The Legends—Wayne Gretzky, Hockey Hall of Fame, archived from the original on September 7, 2005, retrieved August 29, 2008

- Willes 2004, p. 214

- Willes 2004, p. 250

- Willes 2004, p. 251

- McFarlane 1990, p. 183

- Boer 2006, p. 37

- McFarlane 1990, p. 206

- McKinley 2006, p. 245

- McFarlane 1990, p. 210

- "Teams in N.H.L. Join In Suing Ralston Purina", The New York Times, June 26, 1983, retrieved November 12, 2008

- "Blues given to N.H.L.", The New York Times, June 4, 1983, retrieved November 12, 2008

- McFarlane 1990, p. 214

- "Sale of Blues is Complete", The New York Times, July 28, 1983, retrieved November 12, 2008

- "N.H.L. Settles Antitrust Suit", The New York Times, June 28, 1985, retrieved November 12, 2008

- Diamond 1991, p. 245

- Diamond 1991, p. 246

- Diamond 1991, p. 267

- Diamond 1991, p. 271

- Diamond 1991, p. 314

- Steve Smith, Edmonton Oilers Heritage Foundation, archived from the original on March 2, 2012, retrieved January 2, 2009

- Swift, E.M., SI Flashback: Stanley Cup 1986, Sports Illustrated, retrieved January 2, 2009

- Top 10: Game 7's, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved January 2, 2009

- Biggest Stanley Cup playoff chokes, ESPN, retrieved January 2, 2009

- Diamond 1991, p. 289

- Diamond 1991, p. 308

- Todd, Jack (September 17, 2012). "Americans and Bettman have stolen Canada's game". Calgary Herald. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- Finn, Robin (December 6, 1990), "Awarding of new franchises is near", The New York Times, retrieved August 31, 2008

- Finn, Robin (December 7, 1990), "Tampa and Ottawa gain N.H.L. franchises", The New York Times, retrieved August 31, 2008

- Pincus 2006, p. 151

- Knowles, Steve (2007), Edmonton Oilers 2007–08 Media Guide, Edmonton Oilers Hockey Club, p. 249

- Pincus 2006, p. 154

- Diamond 1991, p. 278

- Edmonton's Saddest Hockey Day—The Gretzky Trade, Edmonton Oilers Heritage Foundation, archived from the original on February 1, 2010, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Pincus 2006, p. 168

- Pincus 2006, pp. 164–165

- Pincus 2006, p. 148

- McKinley 2006, p. 230

- Pincus 2006, p. 150

- Duhatschek, Eric (June 18, 1989), "GMs figure Soviets one day will flood market", Calgary Herald, p. E4

- Miller, Mark (February 22, 1999), "Peter's principle", Calgary Sun, p. S4

- Boer 2006, p. 104

- Sweeping Changes, Sports Illustrated, September 27, 2002, retrieved August 8, 2008

- "New rules for rookies", The New York Times, June 20, 1990, archived from the original on October 15, 2007, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Hockey in Europe, National Hockey League, archived from the original on April 5, 2010, retrieved February 25, 2009

- "NHL Totals by Nationality ‑ 2013‑2014 Stats".

- McFarlane 1990, p. 98

- McFarlane 1990, p. 120

- McFarlane 1990, p. 186

- Pincus 2006, p. 162

- Pincus 2006, pp. 110–111

- McFarlane 1990, p. 177

Further reading

- Boer, Peter (2006), The Calgary Flames, Overtime Books, ISBN 1-897277-07-5

- Diamond, Dan (1991), The Official National Hockey League 75th Anniversary Commemorative Book, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-6727-5

- Diamond, Dan; Zweig, Eric (2003), Hockey's Glory Days: The 1950s and '60s, Andrews McMeel Publishing, ISBN 0-7407-3829-1

- MacSkimming, Roy (1996), Cold War, Greystone Books, ISBN 978-0-385-66465-3

- McCown, Bob (2007), McCown's Law: The 100 Greatest Hockey Arguments, Doubleday Canada, ISBN 978-1-55054-473-2

- McFarlane, Brian (1990), 100 Years of Hockey, Summerhill Press, ISBN 0-929091-26-4

- McFarlane, Brian (2004), Best of the Original Six, Fenn Publishing Company, ISBN 1-55168-263-X

- McKinley, Michael (2006), Hockey: A People's History, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-5769-5

- Pincus, Arthur (2006), The Official Illustrated NHL History, Reader's Digest, ISBN 0-88850-800-X

- Willes, Ed (2004), The Rebel League: The Short and Unruly Life of the World Hockey Association, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-8947-3