History of tracheal intubation

Tracheal intubation (usually simply referred to as intubation), an invasive medical procedure, is the placement of a flexible plastic catheter into the trachea. For millennia, tracheotomy was considered the most reliable (and most risky) method of tracheal intubation. By the late 19th century, advances in the sciences of anatomy and physiology, as well as the beginnings of an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, had reduced the morbidity and mortality of this operation to a more acceptable rate. Also in the late 19th century, advances in endoscopic instrumentation had improved to such a degree that direct laryngoscopy had finally become a viable means to secure the airway by the non-surgical orotracheal route. Nasotracheal intubation was not widely practiced until the early 20th century. The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia, critical care medicine, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, pulmonology and surgery.

Tracheotomy

The earliest known depiction of a tracheotomy is found on two Egyptian tablets dating back to circa 3600 BC.[1] The 110-page Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical papyrus that dates to around 1550 BC, also refers to the tracheotomy.[1][2] Tracheotomy was described in an ancient Indian scripture, the Rigveda: the text mentions "the bountiful one who, without a ligature, can cause the windpipe to re-unite when the cervical cartilages are cut across, provided they are not entirely severed."[2][3][4] The Sushruta Samhita (c. 400 BC) is another text from the Indian subcontinent on ayurvedic medicine and surgery that mentions tracheotomy.[5]

The Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BC) condemned the practice of tracheotomy. Warning against the unacceptable risk of death from inadvertent laceration of the carotid artery during tracheotomy, Hippocrates also cautioned that "The most difficult fistulas are those that occur in the cartilaginous areas."[6] Homerus of Byzantium is said to have written of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) saving a soldier from asphyxiation by making an incision with the tip of his sword in the man's trachea.[7]

Despite the concerns of Hippocrates, Galen of Pergamon (129–199) and Aretaeus of Cappadocia (both of whom lived in Rome in the 2nd century AD) credit Asclepiades of Bithynia (c. 124–40 BC) as being the first physician to perform a non-emergency tracheotomy.[8][9] However, Aretaeus warned against the performance of tracheotomy because he believed that incisions made into the tracheal cartilage were prone to secondary wound infections and therefore would not heal. He wrote that "The lips of the wound do not coalesce, for they are both cartilaginous and not of a nature to unite".[10][11] Antyllus, another Greek surgeon who lived in Rome in the 2nd century AD, was reported to have performed tracheotomy when treating oral diseases. He refined the technique to be more similar to that used in modern times, recommending that a transverse incision be made between the third and fourth tracheal rings for the treatment of life-threatening airway obstruction.[10] Antyllus wrote that tracheotomy was not effective however in cases of severe laryngotracheobronchitis because the pathology was distal to the operative site. Antyllus' original writings were lost, but they were preserved by Oribasius (c. 320–400) and Paul of Aegina (c. 625–690), both of whom were Greek physicians as well as historians.[10] Galen clarified the anatomy of the trachea and was the first to demonstrate that the larynx generates the voice.[12][13] Galen may have understood the importance of artificial ventilation, because in one of his experiments he used bellows to inflate the lungs of a dead animal.[14][15]

During the Middle Ages, scientific discoveries were few and far between in much of Europe. However, the scientific culture flourished in other parts of the world. In 1000, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936-1013), an Arab who lived in Al-Andalus, published the 30-volume Kitab al-Tasrif, the first illustrated work on surgery. He never performed a tracheotomy, but he did treat a slave girl who had cut her own throat in a suicide attempt. Al-Zahrawi (known to Europeans as Albucasis) sewed up the wound and the girl recovered, thereby proving that an incision in the larynx could heal. Circa 1020, Ibn Sīnā (980–1037) described the use of tracheal intubation in The Canon of Medicine to facilitate breathing.[16] In the 12th century medical textbook Al-Taisir, Ibn Zuhr (1091–1161) of Al-Andalus (also known as Avenzoar) provided an anatomically correct description of the tracheotomy operation.[17][18]

The Renaissance saw significant advances in anatomy and surgery, and surgeons became increasingly open to surgery on the trachea. Despite this, the mortality rate failed to improve.[10] From 1500 through 1832 there are only 28 known descriptions of successful tracheotomy in the literature.[10] The first detailed descriptions on tracheal intubation and subsequent artificial respiration of animals were from Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) of Brussels. In his landmark book published in 1543, De humani corporis fabrica, he described an experiment in which he passed a reed into the trachea of a dying animal whose thorax had been opened and maintained ventilation by blowing into the reed intermittently.[15][19] Vesalius wrote that the technique could be life-saving. Antonio Musa Brassavola (1490–1554) of Ferrara treated a patient with peritonsillar abscess by tracheotomy after the patient had been refused by barber surgeons. The patient apparently made a complete recovery and Brassavola published his account in 1546. This operation has been identified as the first recorded successful tracheostomy, despite many ancient references to the trachea and possibly to its opening.[10]

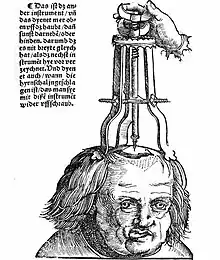

Towards the end of the 16th century, anatomist and surgeon Hieronymus Fabricius (1533–1619) described a useful technique for tracheotomy in his writings, although he had never actually performed the operation himself. He advised using a vertical incision and was the first to introduce the idea of a tracheostomy tube. This was a straight, short cannula that incorporated wings to prevent the tube from advancing too far into the trachea. Fabricius' description of the tracheotomy procedure is similar to that used today. Julius Casserius (1561–1616) succeeded Fabricius as professor of anatomy at the University of Padua and published his own writings regarding technique and equipment for tracheotomy, recommending a curved silver tube with several holes in it. Marco Aurelio Severino (1580–1656), a skillful surgeon and anatomist, performed multiple successful tracheotomies during a diphtheria epidemic in Naples in 1610, using the vertical incision technique recommended by Fabricius. He also developed his own version of a trocar.[20]

In 1620 the French surgeon Nicholas Habicot (1550–1624), surgeon of the Duke of Nemours and anatomist, published a report of four successful "bronchotomies" he had performed.[21] One of these is the first recorded case of a tracheotomy for the removal of a foreign body, in this instance a blood clot in the larynx of a stabbing victim. He also described the first known tracheotomy performed on a pediatric patient. A 14-year-old boy swallowed a bag containing 9 gold coins in an attempt to prevent its theft by a highwayman. The object became lodged in his esophagus, obstructing his trachea. Habicot suggested that the operation might also be effective for patients with inflammation of the larynx. He developed equipment for this surgical procedure that are similar in many ways to modern designs.

Sanctorius (1561–1636) is believed to be the first to use a trocar in the operation. He recommended leaving the cannula in place for a few days following the operation.[22] Early tracheostomy devices are illustrated in Habicot's Question Chirurgicale[21] and Julius Casserius' posthumous Tabulae anatomicae in 1627.[23] Thomas Fienus (1567–1631), Professor of Medicine at the University of Louvain, was the first to use the word "tracheotomy" in 1649, but this term was not commonly used until a century later.[24] Georg Detharding (1671–1747), professor of anatomy at the University of Rostock, treated a drowning victim with tracheostomy in 1714.[25][26][27]

Fearful of complications, most surgeons delayed the potentially life-saving tracheotomy until a patient was moribund, despite the knowledge that irreversible organ damage would have already occurred by that time. This began to change in the early 19th century, when the tracheotomy finally began to be recognized as a legitimate means of treating severe airway obstruction. In 1832, French physician Pierre Bretonneau (1778–1862) employed tracheotomy as a last resort to treat a case of diphtheria.[28] In 1852, Bretonneau's student Armand Trousseau (1801–1867) presented a series of 169 tracheotomies (158 of which were for croup and 11 for "chronic maladies of the larynx").[29] In 1871, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924) published a paper describing the first successful elective human tracheotomy performed to administer general anesthesia.[30][31][32][33] After the death of German Emperor Frederick III from laryngeal cancer in 1888, Sir Morell Mackenzie (1837–1892) and the other treating physicians collectively wrote a book discussing the then-current indications for tracheotomy and when the operation is absolutely necessary.[34]

In the early 20th century, physicians began to use the tracheotomy in the treatment of patients affected by paralytic poliomyelitis who required mechanical ventilation. The currently used surgical tracheotomy technique was described in 1909 by Chevalier Jackson (1865–1958), a professor of laryngology at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.[35] However, surgeons continued to debate various aspects of the tracheotomy well into the 20th century. Many techniques were employed, along with many different surgical instruments and tracheal tubes. Surgeons could not seem to reach a consensus on where or how the tracheal incision should be made, arguing whether the "high tracheotomy" or the "low tracheotomy" was more beneficial. Ironically, the newly developed inhalational anesthetic agents and techniques of general anesthesia actually seemed to increase the risks, with many patients with fatal postoperative complications. Jackson emphasised the importance of postoperative care, which dramatically reduced the mortality rate. By 1965, the surgical anatomy was thoroughly and widely understood, antibiotics were widely available and useful for treating postoperative infections and other major complications of tracheotomy had also become more manageable.

Endoscopy

While all these surgical advances were taking place, many important developments were also taking place in the science of optics. Many new optical instruments with medical applications were invented during the 19th century. In 1805, a German army surgeon named Philipp von Bozzini (1773–1809) invented a device he called the lichtleiter (or light-guiding instrument). This instrument, the ancestor of the modern endoscope, was used to examine the urethra, the human urinary bladder, rectum, oropharynx and nasopharynx.[36][37][38][39] The instrument consisted of a candle within a metal chimney; a mirror on the inside reflected light from the candle through attachments into the relevant body cavity.[40] The practice of gastric endoscopy in humans was pioneered by United States Army surgeon William Beaumont (1785–1853) in 1822 with the cooperation of his patient Alexis St. Martin (1794–1880), a victim of an accidental gunshot wound to the stomach.[41] In 1853, Antonin Jean Desormeaux (1815–1882) of Paris modified Bozzini's lichtleiter such that a mirror would reflect light from a kerosene lamp through a long metal channel.[40] Referring to this instrument as an endoscope (he is credited with coining this term), Desormeaux employed it to examine the urinary bladder. However, like Bozzini's lichtleiter, Desormeaux's endoscope was of limited utility due to its propensity to become very hot during use.[40] In 1868, Adolph Kussmaul (1822–1902) of Germany performed the first esophagogastroduodenoscopy (a diagnostic procedure in which an endoscope is used to visualize the esophagus, stomach and duodenum) on a living human. The subject was a sword-swallower, who swallowed a metal tube with a length of 47 centimeters and a diameter of 13 millimeters.[42][43][44][45] On 2 October 1877, Berlin urologist Maximilian Carl-Friedrich Nitze (1848–1906) and Viennese instrument maker Josef Leiter (1830–1892) introduced the first practical cystourethroscope with an electric light source.[46] The instrument's biggest drawback was the tungsten filament incandescent light bulb (invented by Alexander Lodygin, 1847–1923), which became very hot and required a complicated water cooling system.[40] In 1881, Polish physician Jan Mikulicz-Radecki (1850–1905) created the first rigid gastroscope for practical applications.[47][48][49]

In 1932, Rudolph Schindler (1888–1968) of Germany introduced the first semi-flexible gastroscope.[50] This device had numerous lenses positioned throughout the tube and a miniature light bulb at the distal tip. The tube of this device was 75 centimeters long and 11 millimeters in diameter, and the distal portion was capable of a certain degree of flexion. Between 1945 and 1952, optical engineers (particularly Karl Storz (1911–1996) of the Karl Storz GmbH company of Germany, Harold Hopkins (1918–1995) of England and Mutsuo Sugiura of the Japanese Olympus Corporation) built upon this early work, leading to the development of the first "gastrocamera".[51][52] In 1964, Fernando Alves Martins (born 17 June 1927) of Portugal applied optical fiber technology to one of these early gastrocameras to produce the first gastrocamera with a flexible fiberscope.[53][54] Initially used in esophagogastroduodenoscopy, newer devices were developed in the late 1960s for use in bronchoscopy, rhinoscopy and laryngoscopy. The concept of using a fiberoptic endoscope for tracheal intubation was introduced by Peter Murphy, an English anesthetist, in 1967.[55] By the mid-1980s, the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope had become an indispensable instrument within the pulmonology and anesthesia communities.[56]

Laryngoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation

From Angelo Mariani and Joseph Uzanne (1894). Figures contemporaines tirées de l'Album Mariani, Volume I. Paris:Ernest Flammarion.

In 1854, a Spanish vocal pedagogist named Manuel García (1805–1906) became the first man to view the functioning glottis in a living human. García developed a tool that used two mirrors for which the Sun served as an external light source.[57] Using this device, he was able to observe the function of his own glottic apparatus and the uppermost portion of his trachea. He presented his observations at the Royal Society of London in 1855.[57][58]

In 1858, Eugène Bouchut (1818–1891), a pediatrician from Paris, developed a new technique for non-surgical orotracheal intubation to bypass laryngeal obstruction resulting from a diphtheria-related pseudomembrane. His method involved introducing a small straight metal tube into the larynx, securing it by means of a silk thread and leaving it there for a few days until the pseudomembrane and airway obstruction had resolved sufficiently.[59] Bouchut presented this experimental technique along with the results he had achieved in the first seven cases at the French Academy of Sciences conference on 18 September 1858.[60] The members of the academy rejected Bouchut's ideas, largely as a result of highly critical and negative remarks made by the influential Armand Trousseau.[61] Undaunted, Bouchut later introduced a set of tubes ("Bouchut's tubes") for intubation of the trachea, as an alternative to tracheotomy in cases of diphtheria.

In March 1878, Wilhelm Hack of Freiburg published a paper describing the use of non-surgical orotracheal intubation in the removal of vocal cord polyps.[62] In November of that year, he published another study, this time on the use of orotracheal intubation to secure the airway of a patient with acute glottic edema, progressively introducing sizes 3 through 11 of "Schrotter's graduated triangular vulcanite bougies" into the larynx.[63][64] In 1880, the Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848–1924) reported on his use of orotracheal intubation as an alternative to tracheotomy to allow a patient with glottic edema to breathe, as well as in the setting of general anesthesia with chloroform.[64][65][66] All previous observations of the glottis and larynx (including those of García, Hack and Macewen) had been performed under indirect vision (using mirrors) until 23 April 1895, when Alfred Kirstein (1863–1922) of Germany first described direct visualization of the vocal cords. Kirstein performed the first direct laryngoscopy in Berlin, using an esophagoscope he had modified for this purpose; he called this device an autoscope.[67] The death in 1888 of Emperor Frederick III[34] may have motivated Kirstein to develop the autoscope.[68]

Until 1913, oral and maxillofacial surgery was performed by mask inhalation anesthesia, topical application of local anesthetics to the mucosa, rectal anesthesia, or intravenous anesthesia. While otherwise effective, these techniques did not protect the airway from obstruction and also exposed patients to the risk of pulmonary aspiration of blood and mucus into the tracheobronchial tree. In 1913, Chevalier Jackson was the first to report a high rate of success for the use of direct laryngoscopy as a means to intubate the trachea.[69] Jackson introduced a new laryngoscope blade that had a light source at the distal tip, rather than the proximal light source used by Kirstein.[70] This new blade incorporated a component that the operator could slide out to allow room for passage of an endotracheal tube or bronchoscope.[71]

That same year, Henry H. Janeway (1873–1921) published results he had achieved using a laryngoscope he had recently developed.[72] While practicing at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, Janeway was of the opinion that direct intratracheal insufflation of volatile anesthetics would provide improved conditions for otolaryngologic surgery. With this in mind, he developed a laryngoscope designed for the sole purpose of tracheal intubation. Similar to Jackson's device, Janeway's instrument incorporated a distal light source. Unique however was the inclusion of batteries within the handle, a central notch in the blade for maintaining the tracheal tube in the midline of the oropharynx during intubation and a slight curve to the distal tip of the blade to help guide the tube through the glottis. The success of this design led to its subsequent use in other types of surgery. Janeway was thus instrumental in popularizing the widespread use of direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation in the practice of anesthesiology.[68]

After World War I, further advances were made in the field of intratracheal anesthesia. Among these were those made by Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill (1888–1986). Working at the Queen's Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries in Sidcup with plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies (1882–1960) and anesthetist E. Stanley Rowbotham (1890–1979), Magill developed the technique of awake blind nasotracheal intubation.[73][74][75][76][77][78] Magill devised a new type of angulated forceps (the Magill forceps) that are still used today to facilitate nasotracheal intubation in a manner that is little changed from Magill's original technique.[79] Other devices invented by Magill include the Magill laryngoscope blade,[80] as well as several apparati for the administration of volatile anesthetic agents.[81][82][83] The Magill curve of an endotracheal tube is also named for Magill.

Sir Robert Macintosh (1897–1989) also achieved significant advances in techniques for tracheal intubation when he introduced his new curved laryngoscope blade in 1943.[84] The Macintosh blade remains to this day the most widely used laryngoscope blade for orotracheal intubation.[85] In 1949, Macintosh published a case report describing the novel use of a gum elastic urinary catheter as an endotracheal tube introducer to facilitate difficult tracheal intubation.[86] Inspired by Macintosh's report, P. Hex Venn (who was at that time the anesthetic advisor to the British firm Eschmann Brothers & Walsh, Ltd.) set about developing an endotracheal tube introducer based on this concept. Venn's design was accepted in March 1973, and what became known as the Eschmann endotracheal tube introducer went into production later that year.[87] The material of Venn's design was different from that of a gum elastic bougie in that it had two layers: a core of tube woven from polyester threads and an outer resin layer. This provided more stiffness but maintained the flexibility and the slippery surface. Other differences were the length (the new introducer was 60 cm (24 in), which is much longer than the gum elastic bougie) and the presence of a 35° curved tip that let it be steered around obstacles.[88][89] The concept of using a stylet for replacing or exchanging orotracheal tubes was introduced by Finucane and Kupshik in 1978, using a central venous catheter.[90]

21st century

The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia, critical care medicine, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, pulmonology and surgery. The "digital revolution" of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes that use digital technology such as the CMOS active pixel sensor (CMOS APS) to generate a view of the glottis so that the trachea may be intubated. The Glidescope video laryngoscope is one example of such a device.[91][92]

References

- General

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (2004). ATLS: Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors (7th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: American College of Surgeons. ISBN 978-1-880696-31-6. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Barash, PG; Cullen, BF; Stoelting, RK, eds. (2009). Clinical Anesthesia (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-8763-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Benumof, JL, ed. (2007). Benumof's Airway Management: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-02233-0. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Classen, M, ed. (2002). Gastroenterological endoscopy (1st ed.). Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-1-58890-013-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Doherty, GM, ed. (2010). Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-163515-8. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Levitan, RM (2004). The Airway Cam Guide to Intubation and Practical Emergency Airway Management (1st ed.). Wayne, PA: Airway Cam Technologies. ISBN 978-1-929018-12-3. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Miller, RD, ed. (2000). Anesthesia, Volume 1 (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-07995-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Vilardell, Francisco (2006). Digestive endoscopy in the second millennium: from the lichtleiter to echoendoscopy. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-3-13-139671-6. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Specific

- Pahor, Ahmes L. (2007). "Ear, Nose and Throat in Ancient Egypt". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 106 (8): 677–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100120560. PMID 1402355. S2CID 35712860.

- Frost, EA (1976). "Tracing the tracheostomy". Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 85 (5 Pt.1): 618–24. doi:10.1177/000348947608500509. PMID 791052. S2CID 34938843.

- Stock, CR (1987). "What is past is prologue: a short history of the development of tracheostomy". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 66 (4): 166–9. PMID 3556136.

- Pahor, Ahmes L. (2007). "Ear, Nose and Throat in Ancient Egypt". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 106 (9): 773–9. doi:10.1017/S0022215100120869. PMID 1431512. S2CID 44250683.

- Sushruta (1907). "Introduction". In Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna (ed.). Sushruta Samhita, Volume1: Sutrasthanam. Calcutta: Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna. pp. iv. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Jones, W. H. S. (2009). "Hippocrates in English". The Classical Review. 2 (2): 88–9. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00158688. S2CID 162403363.

- Szmuk, Peter; Ezri, Tiberiu; Evron, Shmuel; Roth, Yehudah; Katz, Jeffrey (2007). "A brief history of tracheostomy and tracheal intubation, from the Bronze Age to the Space Age". Intensive Care Medicine. 34 (2): 222–8. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0931-5. PMID 17999050. S2CID 23486235.

- Gumpert, CG (1794). "Cap. VIII: de morborum cognitione et curatione secundum Asclepiadis doctrinam". Asclepiadis Bithyniae Fragmenta (in Latin). Weimar: Industrie-Comptoir. pp. 133–84. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Yapijakis, C (2009). "Hippocrates of Kos, the father of clinical medicine, and Asclepiades of Bithynia, the father of molecular medicine. Review". In Vivo. 23 (4): 507–14. PMID 19567383. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Goodall, EW (1934). "The story of tracheostomy". British Journal of Children's Diseases. 31: 167–76, 253–72.

- Grillo, H (2003). "Development of tracheal surgery: a historical review. Part 1: techniques of tracheal surgery". Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 75 (2): 610–9. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04108-5. PMID 12607695.

- Galeni Pergameni, C (1956). Galen on anatomical procedures: De anatomicis administrationibus. Edited and translated by Singer CJ. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press/Wellcome Historical Medical Museum. pp. 195–207. See also: "Galen on Anatomical Procedures: De Anatomicis Administrationibus". JAMA. 162 (6): 616. 1956. doi:10.1001/jama.1956.02970230088033.

- "Galen on Anatomical Procedures". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 49 (10): 833. 1956. doi:10.1177/003591575604901017. PMC 1889206.

- Galeni Pergameni, C (1528). "De usu partium corporis humani, libri VII, cap. IV". In Nicolao Regio Calabro (ed.). De usu partium corporis humani, libri VII (in Latin). Paris: Simonis Colinaei. p. 339. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Baker, A. Barrington (1971). "Artificial respiration, the history of an idea". Medical History. 15 (4): 336–51. doi:10.1017/s0025727300016896. PMC 1034194. PMID 4944603.

- Skinner, P (2008). "Unani-tibbi". In Laurie J. Fundukian (ed.). The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine (3rd ed.). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Cengage. ISBN 978-1-4144-4872-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Abdel-Halim, RE (2005). "Contributions of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) to the progress of surgery: a study and translations from his book Al-Taisir". Saudi Med J. 26 (9): 1333–9. PMID 16155644. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Shehata, M (2003). "The Ear, Nose and Throat in Islamic Medicine" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2 (3): 2–5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Vesalius, A (1543). "Cap. XIX-De vivorum sectione nonniulla". De humani corporis fabrica, Libri VII (in Latin). Basel: Johannes Oporinus. pp. 658–63. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- "Nova et Vetera". BMJ. 1 (5179): 1129–30. 1960. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5179.1129. PMC 1966956.

- Habicot, N (1620). Question chirurgicale par laquelle il est démonstré que le chirurgien doit assurément practiquer l'operation de la bronchotomie, vulgairement dicte laryngotomie, ou perforation de la fluste ou du polmon (in French). Paris: Corrozet. p. 108.

- Sanctorii S (1646). Sanctorii Sanctorii Commentaria in primum fen, primi libri canonis Avicennæ (in Latin). Venetiis: Apud Marcum Antonium Brogiollum. p. 1120. OL 15197097M. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Casserius (Giulio Casserio), J; Bucretius, D (1632). Tabulae anatomicae LXXIIX ... Daniel Bucretius ... XX. que deerant supplevit & omnium explicationes addidit (in Latin). Francofurti: Impensis & coelo Matthaei Meriani. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Cawthorne, T; Hewlett, AB; Ranger, D (1959). "Discussion: Tracheostomy To-Day". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 52 (6): 403–5. doi:10.1177/003591575905200602. PMC 1871130. PMID 13667911.

- Detharding, G (1745). "De methodo subveniendi submersis per laryngotomiam (1714)". In Von Ernst Ludwig Rathlef; Gabriel Wilhelm Goetten; Johann Christoph Strodtmann (eds.). Geschichte jetzlebender Gelehrten, als eine Fortsetzung des Jetzlebenden (in Latin). Zelle: Berlegts Joachim Undreas Deek. p. 20. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Wischhusen, HG; Schumacher, GH (1977). "Curriculum vitae of the professor of anatomy, botany and higher mathematics Georg Detharding (1671–1747) at the University of Rostock". Anat Anz (in German). 142 (1–2): 133–40. PMID 339777.

- Price, JL (1962). "The Evolution of Breathing Machines". Medical History. 6 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1017/s0025727300026867. PMC 1034674. PMID 14488739.

- Trousseau, A (1833). "Mémoire sur un cas de tracheotomie pratiquée dans la période extrème de croup". Journal des Connaissances Médico-chirurgicales (in French). 1 (5): 41.

- Trousseau, A (1852). "Nouvelles recherches sur la trachéotomie pratiquée dans la période extrême du croup". Annales de Médecine Belge et étrangère (in French). 1: 279–88. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Trendelenburg, F (1871). "Beiträge zu den Operationen an den Luftwegen" [Contributions to airways surgery]. Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie (in German). 12: 112–33.

- Hargrave, R (1934). "Endotracheal Anaesthesia in Surgery of the Head and Neck". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (6): 633–7. PMC 403396. PMID 20319535.

- Bain, J A; Spoerel, W E (1964). "Observation on the use of cuffed tracheqstomy tubes (with particular reference to the james tube)". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 11 (6): 598–608. doi:10.1007/BF03004104. PMID 14232175.

- Wawersik, Juergen (1991). "History of Anesthesia in Germany". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 3 (3): 235–44. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(91)90167-L. PMID 1878238.

- Mackenzie, M (1888). The case of Emperor Frederick III.: full official reports by the German physicians and by Sir Morell Mackenzie. New York: Edgar S. Werner. p. 276. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Jackson, Chevalier (1909). "Tracheotomy". The Laryngoscope. 19 (4): 285–90. doi:10.1288/00005537-190904000-00003. S2CID 221922284.

- Bozzini, P (1806). "Lichtleiter, eine Erfindung zur Anschauung innerer Theile und Krankheiten nebst der Abbildung". J Practischen Heilkunde Berlin (in German). 24: 107–24.

- Bozzini, P (1810). "Lichtleiter, eine Erfindung zur Anschauung innerer Theile und Krankheiten nebst der Abbildung". Heidelbergische Jahrbücher der Litteratur (in German). Vol. 3. Heidelberg: bey Wöhr und Zimmer. p. 207. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Bush, R; Leonhardt, H; Bush, I; Landes, R (1974). "Dr. Bozzini's Lichtleiter: A translation of his original article (1806)". Urology. 3 (1): 119–23. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(74)80080-4. PMID 4591409.

- Pearlman, SJ (1949). "Bozzini's classical treatise on endoscopy: a translation". Quart Bull Northwest Univ Med School. 23: 332–54.

- Engel, R (2007). "Development of the Modern Cystoscope: An Illustrated History". Medscape Urology. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Beaumont, W; Combe, A (1838). Experiments and observations on the gastric juice, and the physiology of digestion (reprint ed.). Edinburgh: MacLachlan & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-486-69213-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Killian, Gustvan (1911). "The history of bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy". The Laryngoscope. 21 (9): 891–7. doi:10.1288/00005537-191109000-00001. S2CID 73388145.

- Modlin, I. M.; Kidd, M; Lye, KD (2004). "From the Lumen to the Laparoscope". Archives of Surgery. 139 (10): 1110–26. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.10.1110. PMID 15492154.

- Elewaut, A; Cremer, M (2002). "The History of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy—The European Perspective". In Meinhard Classen; et al. (eds.). Gastroenterological endoscopy (1st ed.). Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-58890-013-5. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Vilardell, F (2006). "Rigid gastroscopes". Digestive Endoscopy in the Second Millennium: From the Lichtleiter to Echoendoscopy. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 32–5. ISBN 978-3-13-139671-6. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Mouton, Wolfgang G.; Bessell, Justin R.; Maddern, Guy J. (1998). "Looking Back to the Advent of Modern Endoscopy: 150th Birthday of Maximilian Nitze". World Journal of Surgery. 22 (12): 1256–8. doi:10.1007/s002689900555. PMID 9841754. S2CID 3000907.

- Mikulicz-Radecki, J (1881). "Über Gastroskopie und Ösophagoskopie". Wiener Medizinische Presse (in German). 22: 1405–8, 1437–43, 1473–5, 1505–7, 1537–41, 1573–7, 1629–31.

- Schramm, H; Mikulicz-Radecki, J (1881). "Gastroskopia i ezofagoskopia" [Gastroscopy and oesophagoscopy]. Przegla̧d Lekarski (in Polish). 20: 610.

- Kielan, Wojciech; Lazarkiewicz, Bogdan; Grzebieniak, Zygmunt; Skalski, Adam; Zukrowski, Piotr (2005). "Jan Mikulicz-Radecki: one of the creators of world surgery". The Keio Journal of Medicine. 54 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2302/kjm.54.1. PMID 15832074.

- Schäfer, P K; Sauerbruch, T (2004). "Rudolf Schindler (1888–1968) – 'Vater' der Gastroskopie" [Rudolf Schindler (1888–1968) – 'Father' of Gastroscopy]. Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie (in German). 42 (6): 550–6. doi:10.1055/s-2004-813178. PMID 15190453.

- US 2641977, Tatsuro Uji, Mutsuo Sugiura and Shoji Fukami, "Camera for taking photographs of inner wall of cavity of human or animal bodies", issued June 16, 1953

- "History of endoscopes. Volume 2: Birth of gastrocameras". Olympus Corporation. 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- "History of endoscopes. Volume 3: Birth of fiberscopes". Olympus Corporation. 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Martins, FA (2009). "O Endoscópio". Fernando Alves Martins: A vida e a obra de um homem discreto. Inventor, compositor, curioso, um homem à frente do seu tempo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Murphy, Peter (1967). "A fibre?optic endoscope used for nasal intubation". Anaesthesia. 22 (3): 489–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1967.tb02771.x. PMID 4951601. S2CID 33586314.

- Wheeler M and Ovassapian A, "Fiberoptic endoscopy-aided technique", Chapter 18, p. 423 in Benumof (2007)

- Garcia, Manuel (1854). "Observations on the Human Voice". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 7 (60): 399–410. Bibcode:1854RSPS....7..399G. doi:10.1098/rspl.1854.0094. PMC 5180321. PMID 30163547.

- Radomski, T (2005). "Manuel García (1805–1906):A bicentenary reflection" (PDF). Australian Voice. 11: 25–41. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Bouchut, E (1858). "D'une nouvelle méthode de traitement du croup par le tubage du larynx" [On a new method of treatment for croup by larynx intubation]. Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale de Médecine (in French). 23: 1160–2. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Sperati, G; Felisati, D (2007). "Bouchut, O'Dwyer and laryngeal intubation in patients with croup". Acta Otorhinolaryngolica Italica. 27 (6): 320–3. PMC 2640059. PMID 18320839.

- Trousseau, A (1858). "Du tubage de la glotte et de la trachéotomie" [On intubation of the glottis and tracheotomy]. Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale de Médecine (in French). 23.

- Hack, W (1878). "Über einen fall endolaryngealer exstirpation eines polypen der vorderen commissur während der inspirationspause". Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (in German): 135–7. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Hack, W (1878). "Über die mechanische Behandlung der Larynxstenosen" [On the mechanical treatment of laryngeal stenosis]. Sammlung Klinischer Vorträge (in German). 152: 52–75.

- MacEwen, W. (1880). "Clinical Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy". BMJ. 2 (1022): 163–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1022.163. PMC 2241109. PMID 20749636.

- MacEwen, W. (1880). "General Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy". BMJ. 2 (1021): 122–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1021.122. PMC 2241154. PMID 20749630.

- MacMillan, Malcolm (2010). "William Macewen [1848–1924]". Journal of Neurology. 257 (5): 858–9. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5524-5. PMID 20306068.

- Hirsch, N. P.; Smith, G. B.; Hirsch, P. O. (1986). "Alfred Kirstein". Anaesthesia. 41 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12702.x. PMID 3511764. S2CID 12259652.

- Burkle, Christopher M.; Zepeda, Fernando A.; Bacon, Douglas R.; Rose, Steven H. (2004). "A Historical Perspective on Use of the Laryngoscope as a Tool in Anesthesiology". Anesthesiology. 100 (4): 1003–6. doi:10.1097/00000542-200404000-00034. PMID 15087639. S2CID 36279277.

- Jackson, C (1913). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 17: 507–9. Abstract reprinted in Jackson, Chevalier (1996). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Pediatric Anesthesia. Wiley. 6 (3): 230. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.1996.tb00434.x. ISSN 1155-5645. S2CID 72582327.

- Zeitels, S (1998). "Chevalier Jackson's contributions to direct laryngoscopy". Journal of Voice. 12 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(98)80069-6. PMID 9619973.

- Jackson, C (1922). "I: Instrumentarium" (PDF). A manual of peroral endoscopy and laryngeal surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 17–52. ISBN 978-1-4326-6305-6. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Janeway, Henry H. (1913). "Intra-Tracheal Anesthesia from the Standpoint of the Nose, Throat and Oral Surgeon with a Description of a New Instrument for Catheterizing the Trachea". The Laryngoscope. 23 (11): 1082–90. doi:10.1288/00005537-191311000-00009. S2CID 71549386.

- Rowbotham, ES; Magill, I (1921). "Anæsthetics in the Plastic Surgery of the Face and Jaws". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 14 (Sect Anaesth): 17–27. doi:10.1177/003591572101401402. PMC 2152821. PMID 19981941.

- Magill, I (1923). "The provision for expiration in endotracheal insufflations anaesthesia". The Lancet. 202 (5211): 68–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)37756-5.

- Magill, I (1928). "Endotracheal Anæsthesia". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 22 (2): 85–8. PMC 2101959. PMID 19986772.

- Magill, I (1930). "General Council of Medical Education and Registration". British Medical Journal. 2 (1243): 817–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1243.817-a. PMC 2451624. PMID 20775829.

- Thomas, K. Bryn (1978). "Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill, KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA". Anaesthesia. 33 (7): 628–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1978.tb08426.x. PMID 356665. S2CID 28730699.

- McLachlan, G (2008). "Sir Ivan Magill KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA, (1888–1986)". The Ulster Medical Journal. 77 (3): 146–52. PMC 2604469. PMID 18956794.

- "British Medical Journal". BMJ. 2 (3122): 670. 1871. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.571.670. PMC 2338485. PMID 20770050.

- Magill, I (1926). "An improved laryngoscope for anaesthetists". The Lancet. 207 (5349): 500. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)17109-6.

- Magill, W (1921). "A Portable Apparatus for Tracheal Insufflation Anaesthesia". The Lancet. 197 (5096): 918. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)55592-5.

- Magill, I (1921). "Warming ether vapour for Inhalation". The Lancet. 197 (5102): 1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)24908-3.

- Magill, I (1923). "An apparatus for the administration of nitrous oxide, oxygen, and ether". The Lancet. 202 (5214): 228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)22460-X.

- MacIntosh, R (1943). "A New Laryngoscope". The Lancet. 241 (6233): 205. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)89390-3.

- Scott, Jeanette; Baker, Paul A. (2009). "How did the Macintosh laryngoscope become so popular?". Pediatric Anesthesia. 19: 24–9. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03026.x. PMID 19572841. S2CID 6345531.

- "Reports of Societies". BMJ. 1 (4591): 26–28. 1949. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4591.26-b. S2CID 220027204.

- Venn, P. Hex (1993). "The gum elastic bougie". Anaesthesia. 48 (3): 274–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06936.X. S2CID 56666422.

- Viswanathan, S; Campbell, C; Wood, DG; Riopelle, JM; Naraghi, M (1992). "The Eschmann Tracheal Tube Introducer. (Gum elastic bougie)". Anesthesiology Review. 19 (6): 29–34. PMID 10148170.

- Henderson, J. J. (2003). "Development of the 'gum-elastic bougie'". Anaesthesia. 58 (1): 103–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.296828.x. PMID 12492697. S2CID 34113322.

- Finucane, BT; Kupshik, HL (1978). "A flexible stilette for replacing damaged tracheal tubes". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 25 (2): 153–4. doi:10.1007/BF03005076. PMID 638831.

- Agro, F.; Barzoi, G; Montecchia, F (2003). "Tracheal intubation using a Macintosh laryngoscope or a GlideScope(R) in 15 patients with cervical spine immobilization". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 90 (5): 705–6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg560. PMID 12697606.

- Cooper, Richard M.; Pacey, John A.; Bishop, Michael J.; McCluskey, Stuart A. (2005). "Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 52 (2): 191–8. doi:10.1007/BF03027728. PMID 15684262. S2CID 24151531.

External links

- Videos of direct laryngoscopy recorded with the Airway Cam (TM) imaging system

- Examples of some devices for facilitation of tracheal intubation

- Diagram of performance of the Sellick maneuver

- The CRIC Cricothyrotomy System from Pyng Medical Corporation

- The Rüsch QuickTrach from Teleflex Medical Corporation

- The Portex Cricothyroidotomy Kit (PCK)

- The Melker Emergency Cricothyrotomy Catheter Tray