History of tropical cyclone naming

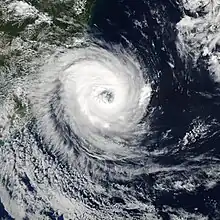

The practice of using names to identify tropical cyclones goes back several centuries, with storms named after places, saints or things they hit before the formal start of naming in each basin. Examples of such names are the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane (also known as the "San Felipe II" hurricane) and the 1938 New England hurricane. The system currently in place provides identification of tropical cyclones in a brief form that is easily understood and recognized by the public. The credit for the first usage of personal names for weather systems is given to the Queensland Government Meteorologist Clement Wragge, who named tropical cyclones and anticyclones between 1887 and 1907. This system of naming fell into disuse for several years after Wragge retired, until it was revived in the latter part of World War II for the Western Pacific. Over the following decades formal naming schemes were introduced for several tropical cyclone basins, including the North and South Atlantic, Eastern, Central, Western and Southern Pacific basins as well as the Australian region and Indian Ocean.

| Part of a series on |

| Tropical cyclones |

|---|

-_Good_pic.jpg.webp) |

|

Outline of tropical cyclones |

However, there has been controversy over the names used at various times, with names being dropped for religious and political reasons. Female names were exclusively used in the basins at various times between 1945 and 2000, and were the subject of several protests. At present tropical cyclones are officially named by one of eleven meteorological services and retain their names throughout their lifetimes. Due to the potential for longevity and multiple concurrent storms, the names reduce the confusion about what storm is being described in forecasts, watches and warnings. Names are assigned in order from predetermined lists once storms have one, three, or ten-minute sustained wind speeds of more than 65 km/h (40 mph), depending on which basin it originates in. Standards vary from basin to basin, with some tropical depressions named in the Western Pacific, while a significant amount of gale-force winds are required in the Southern Hemisphere. The names of significant tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean and Australian region are retired from the naming lists and replaced with another name, at meetings of the World Meteorological Organization's various tropical cyclone committees.

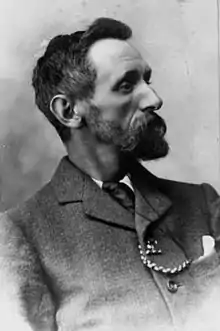

Formal start of naming

The practice of using names to identify tropical cyclones goes back several centuries, with systems named after places, people (like Roman Catholic saints), or things they hit before the formal start of naming in each basin.[1][2][3] Examples include the 1526 San Francisco hurricane (named after Saint Francis of Assisi, whose feast day is observed by Catholics on October 4),[3] the 1834 Padre Ruiz hurricane (named after a then-recently-deceased Catholic priest whose funeral service was being held in the Dominican Republic upon landfall there),[4][5] the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane (named after Lake Okeechobee in the state of Florida, United States, where many of its effects were felt; also named the San Felipe II hurricane in the predominantly-Catholic island of Puerto Rico after a certain Saint Philip with a September 13 feast day),[3] and the 1938 New England hurricane. Credit for the first usage of personal names for weather is generally given to the Queensland Government Meteorologist Clement Wragge, who named tropical cyclones and anticyclones between 1887–1907.[6] Wragge used names drawn from the letters of the Greek alphabet, Greek and Roman mythology and female names, to describe weather systems over Australia, New Zealand and the Antarctic.[2][6] After the new Australian government had failed to create a federal weather bureau and appoint him director, Wragge started naming cyclones after political figures.[7] This system of naming weather systems subsequently fell into disuse for several years after Wragge retired, until it was revived in the latter part of the Second World War.[6] Despite falling into disuse the naming scheme was occasionally mentioned in the press, with an editorial published in the Launceston Examiner newspaper on October 5, 1935 that called for the return of the naming scheme.[1][8] Wragge's naming was also mentioned within Sir Napier Shaw’s “Manual of Meteorology” which likened it to a "child naming waves".[1]

After reading about Clement Wragge, George Stewart was inspired to write a novel, Storm, about a storm affecting California which was named Maria.[7][9] The book was widely read after it was published in 1941 by Random House, especially by United States Army Air Corps and United States Navy (USN) meteorologists during World War II.[1][7] During 1944, United States Army Air Forces forecasters (USAAF) at the newly established Saipan weather center, started to informally name typhoons after their wives and girlfriends.[7][10] This practise became popular amongst meteorologists from the United States Airforce and Navy who found that it reduced confusion during map discussions, and in 1945 the United States Armed Services publicly adopted a list of women's names for typhoons of the Pacific.[7][9] However, they were not able to persuade the United States Weather Bureau (USWB) to start naming Atlantic hurricanes, as the Weather Bureau wanted to be seen as a serious enterprise, and thus felt that it was "not appropriate" to name tropical cyclones while warning the United States public.[1][7][11] They also felt that using women's names was frivolous and that using the names in official communications would have made them look silly.[11] During 1947 the Air Force Hurricane Office in Miami started using the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet to name significant tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean.[1][7] These names were used over the next few years in private/internal communications between weather centres and aircraft, and were not included in public bulletins.[1][7]

During August and September 1950, three tropical cyclones (Hurricanes Baker, Dog and Easy) occurred simultaneously and impacted the United States during August and September 1950, which led to confusion within the media and the public.[1][7][12] As a result, during the next tropical cyclone (Fox), Grady Norton decided to start using the names in public statements and in the seasonal summary.[7][12][13] This practice continued throughout the season, until the system was made official before the start of the next season.[1][9] During 1952, a new International Phonetic Alphabet was introduced, as the old phonetic alphabet was seen as too Anglocentric.[7][14] This led to some confusion with what names were being used, as some observers referred to Hurricane Charlie as "Cocoa."[12][15] Ahead of the following season no agreement could be reached over which phonetic alphabet to use, before it was decided to start using a list of female names to name tropical cyclones.[12][15] During the season the names were used in the press with only a few objections recorded, and as a result public reception to the idea seemed favourable. The same names were reused during 1954 with only one change: Gilda for Gail.[12][15] However, as Hurricanes Carol, Edna, and Hazel affected the populated Northeastern United States, controversy raged with several protests over the use of women’s names as it was felt to be ungentlemanly or insulting to womanhood, or both.[12][15][16] Letters were subsequently received that overwhelmingly supported the practise, with forecasters claiming that 99% of correspondence received in the Miami Weather Bureau supported the use of women’s names for hurricanes.[12][17]

Forecasters subsequently decided to continue with the current practice of naming hurricanes after women, but developed a new set of names ahead of the 1955 season with the names Carol, Edna and Hazel retired for the next ten years.[1][15] However, before the names could be written, a tropical storm was discovered on January 2, 1955 and named Alice.[15] The Representative T. James Tumulty subsequently announced that he intended to introduce legislation that would call on the USWB to abandon its practice of naming hurricanes after women, and suggested that they be named using descriptive terms instead.[18] Until 1960, forecasters decided to develop a new set of names each year.[15] By 1958, the Guam Weather Center had become the Fleet Weather Central/Typhoon Tracking Center on Guam, and had started to name systems as they became tropical storms rather than typhoons.[19] Later that year during the 1958–59 cyclone season, the New Caledonia Meteorological Office started to name tropical cyclones within the Southern Pacific.[6][20] During 1959 the US Pacific Command Commander in Chief and the Joint Chiefs of Staff decided that the various US Navy and Air Force weather units would become one unit based on Guam entitled the Fleet Weather Central/Joint Typhoon Warning Center, which continued naming the systems for the Pacific basin.[19][21]

1960–1990s

In January 1960, a formal naming scheme was introduced for the South-West Indian Ocean by the Mauritius and Madagascan Weather Services. with the first cyclone being named Alix.[22][23][24] Later that year, as meteorology entered a new era with the launching of the world's first meteorological satellite TIROS-1, eight lists of tropical cyclone names were prepared for use in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific basins.[25][26] In the Atlantic it was decided to rotate these lists every four years, while in the Eastern Pacific the names were designed to be used consecutively before being repeated.[25][26] During December 1962, New Caledonia proposed to the third session of the World Meteorological Organisation's Regional Association V, that tropical cyclones in the region should be named using female names.[27] Other members of the association considered using masculine Christian names to the south of the Equator, in order to avoid any confusion with the names used in the Northern Hemisphere.[27] Ultimately the association decided that there was no need for a naming scheme to be introduced to the south of the Equator.[27] However, it had no objections to members naming systems on a national basis provided that the same names were not allocated in neighbouring regions, to different cyclones.[27] During the following year, the Philippine Weather Bureau (later reorganized into PAGASA in 1972) adopted four sets of female Filipino nicknames ending in "ng" from A to Y for use in its self-defined area of responsibility.[28][29][30] Following the international practise of naming tropical cyclones, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology decided at a conference in October 1963 that they would start naming tropical cyclones after women at the start of the 1963–64 cyclone season.[31] The first Western Australian cyclone was subsequently named Bessie on January 6, 1964.[32] In 1965, after two of the Eastern Pacific lists of names had been used, it was decided to start recycling the sets of names on an annual basis like in the Atlantic.[33][34]

At its 1969 national conference, the National Organization for Women passed a motion that called for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) not to name tropical cyclones using only female names.[35] Later that year, during the 1969–70 cyclone season, the New Zealand Meteorological Service (NZMS) office in Fiji started to name tropical cyclones that developed within the South Pacific basin, with the first named Alice on January 4, 1970.[6] Within the Atlantic basin the four lists of names were used until 1971, when the newly established United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration decided to inaugurate a ten-year list of names for the basin.[1] Roxcy Bolton subsequently petitioned the 1971, 1972 and 1973 interdepartmental hurricane conferences to stop the female naming; however, the National Hurricane Center responded by stating that there was a 20:1 positive response to the usage of female names.[1] In February 1975, the NZMS decided to incorporate male names into the naming lists for the South Pacific, from the following season after a request from the Fiji National Council of Women who considered the practice discriminatory.[6] At around the same time the Australian Science Minister ordered that tropical cyclones within the Australian region should carry both men's and women's names, as the minister thought "that both sexes should bear the odium of the devastation caused by cyclones."[6] Male names were subsequently added to the lists for the Southern Pacific and each of the three Australian tropical cyclone warning centres ahead of the 1975–76 season.[6][36][37]

During 1977 the World Meteorological Organization decided to form a hurricane committee, which held its first meeting during May 1978 and took control of the Atlantic hurricane naming lists.[1] During 1978 the Secretary of Commerce Juanita Kreps ordered NOAA administrator Robert White to cease the sole usage of female names for hurricanes.[1] Robert White subsequently passed the order on to the Director of NHC Neil Frank, who attended the first meeting of the hurricane committee and requested that both men’s and women’s names be used for the Atlantic.[1] The committee subsequently decided to accept the proposal and adopted five new lists of male and female names to be used the following year.[38] The lists also contained several Spanish and French names, so that they could reflect the cultures and languages used within the Atlantic Ocean.[39][40] After an agreement was reached between Mexico and the United States, six new sets of male/female names were implemented for the Eastern Pacific basin during 1978.[41] A new list was also drawn up during the year for the Western Pacific and was implemented after Typhoon Bess and the 1979 tropical cyclone conference.[38][42]

As the dual-sex naming of tropical cyclones started in the Northern Hemisphere, the NZMS considered adding ethnic Pacific names to the naming lists rather than the European names that were currently used.[6] As a result of the many languages and cultures in the Pacific there was a lot of discussion surrounding this matter, with one name, "Oni," being dropped as it meant "the end of the world" in one language.[6] One proposal suggested that cyclones be named from the country nearest to which they formed; however, this was dropped when it was realized that a cyclone might be less destructive in its formative stage than later in its development.[6] Eventually it was decided to combine names from all over the South Pacific into a single list at a training course, where each course member provided a list of names that were short, easily pronounced, culturally acceptable throughout the Pacific and did not contain any idiosyncrasies.[6] These names were then collated, edited for suitability, and cross-checked with the group for acceptability.[6] It was intended that the four lists of names should be alphabetical with alternating male and female names while using only ethnic names. However, it was not possible to complete the lists using only ethnic names.[6] As a result, there was a scattering of European names in the final lists, which have been used by the Fiji Meteorological Service and NZMS since the 1980–81 season.[6] During October 1985 the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center had to request an additional list, after the names preselected for that season was used up.[43] As a result, the names Xina, York, Zelda, Xavier, Yolanda, Zeke were subsequently added to the naming lists, while a contingency plan of using the Greek alphabet if all of the names were used up was introduced.[44][45]

New millennium

During the 30th session of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee in November 1997, a proposal was put forward by Hong Kong to give Asian typhoons local names and to stop using the European and American names that had been used since 1945.[46][47] The committee's Training and Research Coordination Group was subsequently tasked to consult with members and work out the details of the scheme in order to present a list of names for approval at the 31st session.[46][47] During August 1998, the group met and decided that each member of the committee would be invited to contribute ten names to the list and that five principles would be followed for the selection of names.[47] It was also agreed that each name would have to be approved by each member and that a single objection would be enough to veto a name.[47] A list of 140 names was subsequently drawn up and submitted to the Typhoon Committee's 32nd session, who after a lengthy discussion approved the list and decided to implement it on January 1, 2000.[47][48][49] It was also decided that the Japan Meteorological Agency would name the systems rather than the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.[47][50]

In 1998, PAGASA conducted "Name a Bagyo Contest", a contest designed to revise the naming scheme for typhoons within the Philippine Area of Responsibility with 140 names submitted in 1999 and the contest prompted PAGASA to begin using the revised naming system with four sets of 25 names and 10 auxiliary names, (replacing its list of female names that used since 1963) rotating every four years, in 2001 and later revised in 2005.[51][52][53][54]

During its annual session in 2000, the WMO/ESCAP Panel on North Indian Tropical Cyclones agreed in principle to start assigning names to cyclonic storms that developed within the North Indian Ocean.[55] As a result of this, the panel requested that each of the eight member countries submit a list of ten names to a rapporteur by the end of 2000.[56] At the 2001 session, the rapporteur reported that of the eight countries involved, only India had refused to submit a list of names, as it had several reservations about assigning names to tropical cyclones.[56] The panel then studied the names and felt that some of the names would not be appealing to the public or the media and thus requested that members submit new lists of names.[56] Over the next couple of years, each country submitted their lists of names and they started to be used during September 2004, when the first tropical cyclone was named Onil by the India Meteorological Department (IMD).[55][57]

At the 22nd hurricane committee in 2000 it was decided that any tropical cyclone that moved from the Atlantic to the Eastern Pacific basin and vice versa would no longer be renamed,[58] provided it remained a tropical cyclone (depression, storm, or hurricane) for its entire crossing of the land mass between the basins. In that case, the National Hurricane Center would be continuously issuing advisories on a regular 6-hour interval without interruption. According to a spokesman for the NHC, "If there is a gap in the advisories, it gets a new name" instead.[59]

Ahead of the 2000–01 season it was decided to start using male names, as well as female names for tropical cyclones developing in the South-West Indian Ocean.[60] During September 2001, RSMC La Reunion proposed that the basin adopt a single circular list of names and that a tropical cyclone have only one name during its lifetime.[61] However, both of these proposals were rejected at the fifteenth session of the RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South-West Indian Ocean during September 2001.[61] During the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season the naming of subtropical cyclones restarted, with names assigned to systems from the main list of names drawn up for that year.[62]

During March 2004, a rare tropical cyclone developed within the Southern Atlantic, about 1,010 km (630 mi) to the east-southeast of Florianópolis in southern Brazil.[63] As the system was threatening the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, a newspaper used the headline "Furacão Catarina," which was presumed to mean "furacão (hurricane) threatening (Santa) Catarina (the state)".[63] However, when the international press started monitoring the system, it was assumed that "Furacão Catarina" meant "Cyclone Catarina" and that it had been formally named in the usual way.[63] During the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season the names pre-assigned for the North Atlantic basin were exhausted and as a result letters of the Greek alphabet were used.[64] There were subsequently a couple of attempts to get rid of the Greek names, as they are seen to be inconsistent with the standard naming convention used for tropical cyclones, generally unknown and confusing to the public.[65] However, none of the attempts succeeded and the Greek alphabet was used again in 2020, when the list of names for the Atlantic Ocean was used up.[65][66][67] After multiple highly catastrophic and damaging Greek-named storms in 2020, however (examples being Zeta, Eta, and Iota) along with the overarching concerns about the confusing and inconsistent nature of the system, the WMO officially discontinued the use of the Greek alphabet to name storms in 2021, instead implementing a supplemental list of regular, replaceable names in both the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific basins in the event either basin experiences a season that exhausts the pre-designated names in the original lists.[68]

Ahead of the 2007 hurricane season, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) and the Hawaii State Civil Defense requested that the hurricane committee retire eleven names from the Eastern Pacific naming lists.[69] However, the committee declined the request and noted that its criteria for the retirement of names was "well defined and very strict."[70] It was felt that while the systems may have had a significant impact on the Hawaiian Islands, none of the impacts were major enough to warrant the retirement of the names.[70] It was also noted that the committee had previously not retired names for systems that had a greater impact than those that had been submitted.[70] The CPHC also introduced a revised set of Hawaiian names for the Central Pacific, after they had worked with the University of Hawaii Hawaiian Studies Department to ensure the correct meaning and appropriate historical and cultural use of the names.[69][71]

On April 22, 2008 the newly established tropical cyclone warning centre in Jakarta, Indonesia named its first system: Durga, before two sets of Indonesian names were established for their area of responsibility ahead of the 2008–09 season.[72][73] At the same time the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, merged their three lists into one national list of names.[74][75] The issue of tropical cyclones being renamed when they moved across 90°E into the South-West Indian Ocean, was subsequently brought up during October 2008 at the 18th session of the RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee.[76] However, it was decided to postpone the matter until the following committee meeting so that various consultations could take place.[76] During the 2009 Tropical Cyclone RSMCs/TCWCs Technical Coordination Meeting, it was reaffirmed that a tropical cyclone name should be retained throughout a system's lifetime, including when moving from one basin to another, to avoid confusion.[77][78] As a result, it was proposed at the following year's RA I tropical cyclone committee, that systems stopped being renamed when they moved into the South-West Indian Ocean from the Australian region.[78] It was subsequently agreed that during an interim period, cyclones that moved into the basin would have a name attached to their existing name, before it was stopped at the start of the 2012–13 season.[78][79] Tropical Cyclone Bruce was subsequently the first tropical cyclone not to be renamed, when it moved into the South-West Indian Ocean during 2013-14.[79] During March 12, 2010, public and private weather services in Southern Brazil, decided to name a tropical storm Anita in order to avoid confusion in future references.[80] A naming list was subsequently set up by the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center with the names Arani, Bapo and Cari subsequently taken from that list during 2011 and 2015.[81][82]

At its twenty-first session in 2015, the RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee reviewed the arrangements for naming tropical storms and decided that the procedure was in need of a "very urgent change".[83] In particular, it was noted that the procedure did not take into account any of the significant improvements in the science surrounding tropical cyclones and that it was biased due to inappropriate links with some national warning systems.[83] The committee subsequently decided that three lists of names would rotate from year to year, with any names used being automatically replaced at the next RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee.[83] During its twenty-third session in 2019, the committee noticed some inconsistency between the operational plan and the WMO technical regulations which defined the roles and responsibilities of tropical cyclone RSMC's.[84] As a result, the committee decided to acknowledge the authority of RSMC La Reunion and gave them the right to name tropical cyclones.[84] During 2020, a new list of names was issued by the panel for tropical cyclones, as the majority of the names in the existing list had been used.

Modern day

| Tropical cyclone naming institutions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | Institution | Area of responsibility | |

| Northern Hemisphere | |||

| North Atlantic Eastern Pacific | United States National Hurricane Center | Equator northward, European and African Atlantic Coasts – 140°W | [85] |

| Central Pacific | United States Central Pacific Hurricane Center | Equator northward, 140°W - 180° | [85] |

| Western Pacific | Japan Meteorological Agency PAGASA | Equator – 60°N, 180 – 100°E 5°N – 21°N, 115°E – 135°E | [86] [87] |

| North Indian Ocean | India Meteorological Department | Equator northward, 100°E – 40°E | [88] |

| Southern Hemisphere | |||

| South-West Indian Ocean | Mauritius Meteorological Services Météo Madagascar Météo France Reunion | Equator – 40°S, 55°E – 90°E Equator – 40°S, African Coast – 55°E Equator – 40°S, African Coast – 90°E | [89] |

| Australian region | Indonesian Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Papua New Guinea National Weather Service Australian Bureau of Meteorology | Equator – 10°S, 90°E – 141°E Equator – 10°S, 141°E – 160°E 10°S – 40°S, 90°E – 160°E | [75] |

| Southern Pacific | Fiji Meteorological Service Meteorological Service of New Zealand | Equator – 25°S, 160°E – 120°W 25°S – 40°S, 160°E – 120°W | [75] |

| South Atlantic | Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center (Unofficial) | Equator – 35°S, Brazilian Coast – 20°W | [81] |

At present tropical cyclones are officially named by one of eleven warning centres and retain their names throughout their lifetimes to provide ease of communication between forecasters and the general public regarding forecasts, watches, and warnings.[7] Due to the potential for longevity and multiple concurrent storms, the names are thought to reduce the confusion about what storm is being described.[7] Names are assigned in order from predetermined lists once storms have one, three, or ten-minute sustained wind speeds of more than 65 km/h (40 mph) depending on which basin it originates in.[85][89][88] However, standards vary from basin to basin, with some tropical depressions named in the Western Pacific, while tropical cyclones have to have gale-force winds occurring near the center before they are named within the Southern Hemisphere.[75][89]

Any member of the World Meteorological Organisation's hurricane, typhoon and tropical cyclone committees can request that the name of a tropical cyclone be retired or withdrawn from the various tropical cyclone naming lists.[75][85][86] A name is retired or withdrawn if a consensus or majority of members agree that the tropical cyclone has acquired a special notoriety, such as causing a large number of deaths and amounts of damage, impacts or for other special reasons.[85] Any tropical cyclone names assigned by the Papua New Guinea National Weather Service are automatically retired regardless of any damage caused.[75] A replacement name is then submitted to the committee concerned and voted upon, but these names can be rejected and replaced for various reasons.[85][86] These reasons include the spelling and pronunciation of the name, its similarity to the name of a recent tropical cyclone or on another list of names, and the length of the name for modern communication channels such as social media.[74][85] PAGASA also retires the names of significant tropical cyclones, when they have caused at least ₱1 billion in damage and/or have caused at least 300 deaths.[90] There are no names retired within the North Indian Ocean or the South-West Indian Ocean, as names are only used once in each basin before being replaced.[88][89]

See also

References

- Dorst, Neal M (October 23, 2012). "They Called the Wind Mahina: The History of Naming Cyclones". United States Hurricane Research Division. Slides 8–72.

- Adamson, Peter (September 2003). "Clement Lindley Wragge and the naming of weather disturbances". Weather. 58 (9): 359–363. Bibcode:2003Wthr...58..359A. doi:10.1256/wea.13.03.

- Mújica-Baker, Frank. Huracanes y tormentas que han afectado a Puerto Rico (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el Manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. pp. 3–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Neely, Wayne (2016). The Greatest and Deadliest Hurricanes of the Caribbean and the Americas: The Stories Behind the Great Storms of the North Atlantic. iUniverse. p. 285. ISBN 9781532011504. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Longshore, David (2010). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones, New Edition (revised ed.). Infobase Publishing. p. 342. ISBN 9781438118796. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Smith, Ray (1990). "What's in a Name?" (PDF). Weather and Climate. 10 (1): 24–26. doi:10.2307/44279572. JSTOR 44279572. S2CID 201717866. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016.

- Landsea, Christopher W; Dorst, Neal M (June 1, 2014). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

- Barnard, G. M (October 5, 1935). "Letters to the Editor: Quite Weatherly". The Examiner. Launceston, Tasmania. p. 15. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- Cry, George (July 1958). Bristow, Gerald C (ed.). "Naming hurricanes and typhoons". Mariners Weather Log. 2 (4): 109. hdl:2027/uc1.b3876059. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- 70th anniversary of women's names used for typhoons. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Warrilow, Chrissy (September 7, 2014). "Why Hurricanes are Named". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- Witten, Don (2010). "What's in a Name? A Hurricane by Any Name Can Be a Killer". Weatherwise. 34 (4): 71. doi:10.1080/00431672.1981.9931969.

- Norton, Grady (January 1951). "Hurricanes of the 1950 Season" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 79 (1): 8–15. Bibcode:1951MWRv...79....8N. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-79.1.8. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- "What's in a name? – The Phonetic Alphabet goes International" (PDF). Topics of the Weather Bureau. 11 (3): 36. March 1952. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Padgett, Gary (2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary July 2007". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- "Decide Next Month On Use Of Girl's Names For Hurricanes". The Times News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. December 22, 1954. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "Girl's Names For Storms Are Criticized In North". Miami Daily News. October 20, 1954. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "Favors Law To Stop Girls' Names For Hurricanes". Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. March 20, 1955. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Anstett, Richard (April 30, 1998). "JTWC Formation, 1958–1959". History of the Joint Typhoon Warning Center up to 1998. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- Kerr, Ian S (March 1, 1976). "Tropical Storms and Hurricanes in the Southwest Pacific: November 1939 to May 1969" (PDF). pp. 23–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- Fleet Weather Central; Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Annual Typhoon Report: 1959 (PDF) (Report). p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Tropical Cyclone Warning System and General Information". Mauritius Meteorological Services. 2012. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- W.B., Issues 36–38. South Africa Weather Bureau. 1960.

- RSMC La Reunion Tropical Cyclone Centre. South-West Indian Ocean Cyclone Season: 2000–01 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Seasonal Summary). Météo-France. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- Kohler, Joseph P, ed. (March 1960). "New Procedure for naming Tropical Cyclones in the North Atlantic". Mariners Weather Log. 4 (2): 34. hdl:2027/uc1.b3876059. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- Kohler, Joseph P, ed. (July 1960). "On The Editors Desk: First Weather Satellite/Names for North Pacific Tropical Cyclones". Mariners Weather Log. 4 (4): 105–107. hdl:2027/uc1.b3876059. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- Regional Association V (South-West Pacific) Abridged Final Report of the Third Session Noumea, November 5 - 17, 1962 (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 31–32. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- Tropical Cyclones of 1963. Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration. p. 45.

- "Naming of Tropical Cyclones". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original on December 3, 1998.

- Dioquino, Rose-an Jessica (October 7, 2011). "From Rosing to Pedring: A storm by any other name". GMA News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- "In Queensland this week". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory. October 10, 1963. p. 2. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- "Tropical Cyclones Frequently Asked Questions". 14. When did the naming of cyclones begin?. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone summary: November 2007". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- Samenow, Jason (June 6, 2014). "Himicanes and hericanes: In 1970s, some argued male-named hurricanes would not be respected". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- DeAngellis, Richard M (March 1976). Wison, Elwyn E (ed.). Hurricane Alley: Australian Tropical Cyclone Names. Mariners Weather Log (Report). Vol. 20. pp. 82–83. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- "Sex-Shift in Australia: A Cyclone Named 'Alan'". New York Times. Reuters. September 30, 1975. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- The Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (May 1978). National Hurricane Operational Plan: 1978 (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- McAdie, Colin J; Landsea, Christopher W; Neumann, Charles J; David, Joan E; Blake, Eric S; Hammer, Gregory R (August 20, 2009). Tropical Cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean, 1851 – 2006 (PDF) (Sixth ed.). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- Padgett, Gary (January 1, 2008). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone summary: August 2007". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Big Blows to get his and her names". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Daytona Beach, Florida. May 12, 1978. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- Naval Oceanography Command Center; Joint Typhoon Warning Center. "Chapter III: Summary of Tropical Cyclones" (PDF). Annual Typhoon Report: 1979 (Report). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2014.

- Kirkman, Don (October 15, 1985). "Hurricanes hitting Southwest? They do". The Lewiston Journal. Lewiston, Maine. p. 25.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary: February 2002". Australian Severe Weather. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- Carnahan, Robert L. National Hurricane Operations Plan 1987 (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2015.

- Lomarda, Nanette C, ed. (September 1998). "The ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Newsletter" (PDF). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Zhou, Xiao; Lei, Xiaotu (2012). "Summary of retired typhoons within the Western North Pacific Ocean". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 1 (1): 23–32. doi:10.6057/2012TCRR01.03. ISSN 2225-6032.

- "Northwest Pacific Basin Names". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Lomarda, Nanette C, ed. (July 1999). "The ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Newsletter" (PDF). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1998). "Appendix B — Tropical Cyclone Names" (PDF). 1998 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. pp. 199–200. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Fernandez, Ruby A. (August 10, 2007). "Typhoon names? No shortage here". The Philippine Star. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- "How Are Tropical Cyclones Named". Panahon.TV. January 4, 2019. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- Eugenio, Ara (October 30, 2020). "Why Does PAGASA Name Typhoons After People?". Reportr. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- "How Pagasa names storms". Yahoo! News Southeast Asia. August 1, 2013. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- RSMC — Tropical Cyclones New Delhi (January 2015). Report on Cyclonic Disturbances over North Indian Ocean during 2014 (PDF) (Report). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones (April 15, 2004). WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones Thirty-First Session (PDF) (Final Report). pp. 8, 54, 55, 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- WMO/ESCAP panel on Tropical Cyclones (April 15, 2004). WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones: Thirty-Second Session (PDF) (Final Report). p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee (2000). RA IV Hurricane Committee 24th Session (PDF) (Final Report). p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 19, 2003. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Kaye, Ken (June 29, 2013). "Some quirky tropical storms at times hit both Atlantic, Pacific oceans". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- RSMC La Reunion Tropical Cyclone Centre (August 31, 2015). "How are the names chosen?". Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (2001). RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee: Fifteenth session (PDF) (Final Report). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2005. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Guishard, Mark P (March 14, 2006). "Boundary Layer Winds in Fabian's Eyewall" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary: March 2004". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Beven, John L; Avila, Lixion A; Blake, Eric S; Brown, Daniel P; Franklin, James L; Knabb, Richard D; Pasch, Richard J; Rhome, Jamie R; Stewart, Stacy R (March 1, 2008). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005". Monthly Weather Review. 136 (3): 1109–1173. Bibcode:2008MWRv..136.1109B. doi:10.1175/2007MWR2074.1.

- Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology (March 10, 2010). New action items: 64th IHC action items: Replace Backup Tropical Cyclone "Greek Alphabet" Name List with Secondary Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Name List (PDF) (Report). pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee (2006). RA IV Hurricane Committee 28th Session (PDF) (Report). pp. 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "With #Alpha, 2020 Atlantic tropical storm names go Greek". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Freedman, Andrew. "Weather panel ends use of Greek names for Atlantic hurricanes, retires deadly 2020 storms". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- 61st IHC action items (PDF) (Report). November 29, 2007. pp. 5–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee (February 1, 2008). RA IV Hurricane Committee 29th Session (PDF) (Final Report). pp. 7, 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center (May 21, 2007). "NOAA announces Central Pacific hurricane season outlook" (Press release). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Paterson, Linda (October 1, 2008). Tropical Cyclone Durga (PDF) (Report). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (2008). RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee Twelfth Session (PDF) (Final Report). pp. 6, 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. November 10, 2014. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (2023). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2023 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (April 15, 2004). RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee: Eighteenth session (PDF) (Final Report). p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- Sixth Tropical Cyclone RSMCs/TCWCs Technical Coordination Meeting (PDF) (Report). October 19, 2012. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee. RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee Nineteenth Session (PDF) (Final Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- Caroff, Philippe. FAQ B: Nom des cyclones tropicaux Sujet B4) Qu'arrive-t-il au nom d'un cyclone lorsqu'il change de zone de responsabilité?. Meteo France La Réunion. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Padgett, Gary. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks March 2010". Australian Severe Weather. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- "NORMAS DA AUTORIDADE MARÍTIMA PARA AS ATIVIDADES DE METEOROLOGIA MARÍTIMA NORMAM-19 1a REVISÃO" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy. 2018. p. C-1-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Masters, Jeff (March 11, 2015). "Subtropical Storm Cari Forms Near Brazil; South Pacific's Cyclone Pam a Cat 4". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (July 1, 2016). RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee Twenty-First Session (Final Report). p. 8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (November 25, 2020). RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee Twenty-Third Session (PDF) (Final Report). p. 15-16. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee (May 9, 2023). Hurricane Operational Plan for North America, Central America and the Caribbean 2023 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- WMO/ESCAP Typhoon Committee (2023). Typhoon Committee Operational Manual: Meteorological Component 2023 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization.

- "Why and how storms get their names". GMA News. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea: 2019 (PDF) (Report) (2019 ed.). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (2021). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-West Indian Ocean (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization.

- "PAGASA replaces names of 2014 destructive typhoons" (Press release). Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. February 5, 2015. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

External links

- AskBOM: How do tropical cyclones get their names? on YouTube

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology Archived 2009-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- India Meteorological Department

- Indonesian Meteorological Department

- Japan Meteorological Agency

- Mauritius Meteorological Services

- Météo-France –La Reunion

- Meteorological Service of New Zealand Limited

- United States Central Pacific Hurricane Center

- United States National Hurricane Center