Hobson's choice

A Hobson's choice is a free choice in which only one thing is actually offered. The term is often used to describe an illusion that multiple choices are available. The best known Hobson's choice is "I'll give you a choice: take it or leave it", wherein "leaving it" is strongly undesirable.

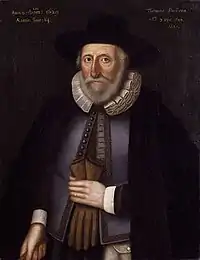

The phrase is said to have originated with Thomas Hobson (1544–1631), a livery stable owner in Cambridge, England, who offered customers the choice of either taking the horse in his stall nearest to the door or taking none at all.

Origins

According to a plaque underneath a painting of Hobson donated to Cambridge Guildhall, Hobson had an extensive stable of some 40 horses. This gave the appearance to his customers that, upon entry, they would have their choice of mounts, when in fact there was only one: Hobson required his customers to take the horse in the stall closest to the door. This was to prevent the best horses from always being chosen, which would have caused those horses to become overused.[1] Hobson's stable was located on land that is now owned by St Catharine's College, Cambridge.[2]

Early appearances in writing

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first known written usage of this phrase is in The rustick's alarm to the Rabbies, written by Samuel Fisher in 1660:[3]

If in this Case there be no other (as the Proverb is) then Hobson's choice...which is, chuse whether you will have this or none.

It also appears in Joseph Addison's paper The Spectator (No. 509 of 14 October 1712);[4] and in Thomas Ward's 1688 poem "England's Reformation", not published until after Ward's death. Ward wrote:

Where to elect there is but one,

'Tis Hobson's choice—take that, or none.[5]

Modern use

The term "Hobson's choice" is often used to mean an illusion of choice, but it is not a choice between two equivalent options, which is a Morton's fork, nor is it a choice between two undesirable options, which is a dilemma. Hobson's choice is one between something or nothing.

John Stuart Mill, in his book Considerations on Representative Government, refers to Hobson's choice:

When the individuals composing the majority would no longer be reduced to Hobson's choice, of either voting for the person brought forward by their local leaders, or not voting at all.[6]

In another of his books, The Subjection of Women, Mill discusses marriage:

Those who attempt to force women into marriage by closing all other doors against them, lay themselves open to a similar retort. If they mean what they say, their opinion must evidently be, that men do not render the married condition so desirable to women, as to induce them to accept it for its own recommendations. It is not a sign of one's thinking the boon one offers very attractive, when one allows only Hobson's choice, 'that or none'.... And if men are determined that the law of marriage shall be a law of despotism, they are quite right in point of mere policy, in leaving to women only Hobson's choice. But, in that case, all that has been done in the modern world to relax the chain on the minds of women, has been a mistake. They should have never been allowed to receive a literary education.[7]

A Hobson's choice is different from:

- Dilemma: a choice between two or more options, none of which are attractive.

- False dilemma: only certain choices are considered, when in fact there are others.

- Catch-22: a logical paradox arising from a situation in which an individual needs something that can only be acquired by not being in that very situation.

- Morton's fork, and a double bind: choices yield equivalent and, often, undesirable results.

- Blackmail and extortion: the choice between paying money (or some non-monetary good or deed) or risk suffering an unpleasant action.

A common error is to use the phrase "Hobbesian choice" instead of "Hobson's choice", confusing the philosopher Thomas Hobbes with the relatively obscure Thomas Hobson.[8][9][10] (It is possible the confusion is between "Hobson's choice" and a "Hobbesian trap", which refers to the situation in which a state attacks another out of fear.)[11][12][13][14]

Common law

In Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha (1983), Justice Byron White dissented and classified the majority's decision to strike down the "one-house veto" as unconstitutional as leaving Congress with a Hobson's choice. Congress may choose between "refrain[ing] from delegating the necessary authority, leaving itself with a hopeless task of writing laws with the requisite specificity to cover endless special circumstances across the entire policy landscape, or in the alternative, to abdicate its lawmaking function to the executive branch and independent agency".

In Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 U.S. 617 (1978),[15] the majority opinion ruled that a New Jersey law which prohibited the importation of solid or liquid waste from other states into New Jersey was unconstitutional based on the Commerce Clause. The majority reasoned that New Jersey cannot discriminate between the intrastate waste and the interstate waste without due justification. In dissent, Justice Rehnquist stated:

[According to the Court,] New Jersey must either prohibit all landfill operations, leaving itself to cast about for a presently nonexistent solution to the serious problem of disposing of the waste generated within its own borders, or it must accept waste from every portion of the United States, thereby multiplying the health and safety problems which would result if it dealt only with such wastes generated within the State. Because past precedents establish that the Commerce Clause does not present appellees with such a Hobson's choice, I dissent.

In Monell v. Department of Social Services of the City of New York, 436 U.S. 658 (1978),[16] the judgement of the court was that

[T]here was ample support for Blair's view that the Sherman Amendment, by putting municipalities to the Hobson's choice of keeping the peace or paying civil damages, attempted to impose obligations to municipalities by indirection that could not be imposed directly, thereby threatening to "destroy the government of the states".

In the South African Constitutional Case MEC for Education, Kwa-Zulu Natal and Others v Pillay, 2008 (1) SA 474 (CC)[17] Chief Justice Langa for the majority of the Court (in Paragraph 62 of the judgement) writes that:

The traditional basis for invalidating laws that prohibit the exercise of an obligatory religious practice is that it confronts the adherents with a Hobson's choice between observance of their faith and adherence to the law. There is however more to the protection of religious and cultural practices than saving believers from hard choices. As stated above, religious and cultural practices are protected because they are central to human identity and hence to human dignity which is in turn central to equality. Are voluntary practices any less a part of a person's identity or do they affect human dignity any less seriously because they are not mandatory?

In Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis (2018), Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented and added in one of the footnotes that the petitioners "faced a Hobson’s choice: accept arbitration on their employer’s terms or give up their jobs".

In Trump et al v. Mazars USA, LLP, US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia No. 19-5142, 49 (D.C. Cir. 11 October 2019) ("[w]orse still, the dissent’s novel approach would now impose upon the courts the job of ordering the cessation of the legislative function and putting Congress to the Hobson’s Choice of impeachment or nothing.").

In Meriwether v. Hartop,[18] the court addressed the university's offer, "Don’t use any pronouns or sex-based terms at all." It wrote, "The effect of this Hobson’s Choice is that Meriwether must adhere to the university’s orthodoxy (or face punishment). This is coercion, at the very least of the indirect sort."

See also

References

- Barrett, Grant (15 April 2009). "What's a "Hobson's Choice"? (minicast)". A Way with Words, a fun radio show and podcast about language. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Thomas Hobson: Hobson's Choice and Hobson's Conduit". CreatingMyCambridge.

- See Samuel Fisher. "Rusticus ad academicos in exercitationibus expostulatoriis, apologeticis quatuor the rustick's alarm to the rabbies or The country correcting the university and clergy, and ... contesting for the truth ... : in four apologeticall and expostulatory exercitations : wherein is contained, as well a general account to all enquirers, as a general answer to all opposers of the most truly catholike and most truly Christ-like Chistians called Quakers, and of the true divinity of their doctrine : by way of entire entercourse held in special with four of the clergies chieftanes, viz, John Owen ... Tho. Danson ... John Tombes ... Rich. Baxter ." Europeana. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- See The Spectator with Notes and General Index, the Twelve Volumes Comprised in Two. Philadelphia: J.J. Woodward. 1832. p. 272. Retrieved 4 August 2014. via Google Books

- Ward, Thomas (1853). English Reformation, A Poem. New York: D.& J. Sadlier & Co. p. 373. Retrieved 8 August 2014. via Internet Archive

- See Mill, John Stuart (1861). Considerations on Representative Government (1 ed.). London: Parker, Son, & Bourn. p. 145. Retrieved 23 June 2014. via Google Books

- Mill, John Stuart (1869). The Subjection of Women (1869 first ed.). London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer. pp. 51–2. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Hobbes, Thomas (1982) [1651]. Leviathan, or the Matter, Form, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil. New York: Viking Press.

- Martinich, A. P. (1999). Hobbes: A Biography. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49583-7.

- Martin, Gary (1965). "Hobson's Choice". The Phrase Finder. 93 (17): 940. PMC 1928986. PMID 20328396. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "The Hobbesian Trap" (PDF). 21 September 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Sunday Lexico-Neuroticism". boaltalk.blogspot.com. 27 July 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- Levy, Jacob (10 June 2003). "The Volokh Conspiracy". volokh.com. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Editor: "Amazingly, some writers have confused the obscure Thomas Hobson with his famous contemporary, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes. The resulting malapropism is beautifully grotesque". Garner, Bryan (1995). A Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 404–405.

- "City of Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 U.S. 617 (1978)".

- "Monell v. Department of Soc. Svcs. - 436 U.S. 658 (1978)". justicia.com. US Supreme Court. 6 June 1978. 436 U.S. 658. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "MEC for Education: Kwazulu-Natal and Others v Pillay (CCT 51/06) [2007] ZACC 21; 2008 (1) SA 474 (CC); 2008 (2) BCLR 99 (CC) (5 October 2007)". saflii.org.

- Meriwether v. Hartop, US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit No. 20-3289 (26 March 2021).

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 553.