Hö'elün

Hö'elün (Mongolian: ᠥᠭᠡᠯᠦᠨ, Ö’elün Üjin (lit. 'Lady Ö’elün'), fl. 1162–1210) was a Mongolian noblewoman and the mother of Temüjin, better known as Genghis Khan. She played a major role in his rise to power, as described in the The Secret History of the Mongols.

Born into the Olkhonud clan of the Qonggirad tribe, Hö'elün was originally married to Chiledu, a Merkit aristocrat; she was however captured shortly after her wedding by Yesügei, an important member of the Mongols, who abducted her to be his primary wife. She and Yesügei had four sons and one daughter: Temüjin, Qasar, Hachiun, Temüge, and Temülen. After Yesügei was fatally poisoned and the Mongols abandoned her family, Hö'elün shepherded all her children through poverty to adulthood—her resilience and organisational skills have been remarked upon by historians. She continued to play an important role after Temüjin's marriage to Börte—together, the two women managed his camp and provided him with advice. Hö'elün married Münglig, an old retainer of Yesügei, in thanks for his support after a damaging defeat in 1187; however, her personal life suffered greatly after Temüjin's 1206 coronation as Genghis Khan. Her date of death is unknown.

Biography

Early life and initial marriages

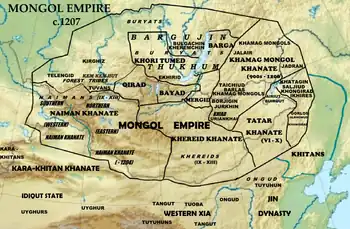

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, a mid-13th century epic poem which retold the formation of the Mongol Empire, Hö'elün was born into the Olkhonud clan of the Qonggirad tribe. The Qonggirad lived along the Greater Khingan mountain range south of the Ergüne river, in modern-day Inner Mongolia, with the Olkhonud living near the source of the Khalkha River.[1] When she grew up to be an "unusually beautiful" young woman, her parents arranged a marriage for her to Chiledu, the brother of the chief of the Merkit tribe; they were wed in a formal ceremony in Olkhonud lands when Hö'elün was around fifteen years old.[2] As the couple were travelling back to Chiledu's homelands, they were ambushed by Mongols who were out hawking. They had noticed Hö'elün's beauty and good health—the 17th-century Altan Tobchi chronicle notes that they had ascertained her fertility from the colour of the ground she had urinated on—and their leader, an aristocratic ba'atur named Yesügei, decided to take Hö'elün as his own wife.[3] Knowing that her outnumbered husband would certainly be killed, Hö'elün urged Chiledu to flee, giving him her blouse so he could remember her scent.[4]

The practice of bride kidnapping was not uncommon on the steppe. However, according to the historian Anne Broadbridge, it caused "long-term social weaknesses" among the tribes, as can be seen from later events in Hö'elün's life.[5] Though Chiledu never attempted to retrieve the bride he had spent time and money negotiating for, possibly because of Yesügei's renown as a leader, the Merkit did not forget their grudge, which later spiralled into a blood feud.[6] Hö'elün was also isolated from her Olkhonud family, whom Yesügei probably never even met; she would be unable to ask them to help her and Yesügei's children in later, harder years.[7] The event was omitted from most official chronicles and only appears in full in the Secret History.[8] Yesügei had previously married another woman, usually named Sochigel by historians, who had already given birth to a son named Behter.[9] Hö'elün however became Yesügei's primary wife, for reasons that are not entirely clear. Broadbridge speculates that her upbringing, which had previously made her eligible to be the valued wife of a chief's brother, placed her higher in Yesügei's eyes than a woman of lower status.[10]

Hö'elün gave birth to her and Yesugei's first son at a place the Secret History records as Delüün Boldog on the Onon River; this has been variously identified at either Dadal in Khentii Province or in southern Agin-Buryat Okrug, in modern-day Russia.[11] The date is similarly controversial, as historians favour different dates: 1155, 1162 or 1167.[12] The historian Paul Ratchnevsky notes that the date may not have been recorded at all.[13] The boy was named Temüjin, a word of uncertain meaning.[14] Several legends surround Temüjin's birth. The most prominent is that of a blood clot he clutched in his hand as he was born, an Asian folklorish motif which indicated the child would be a warrior.[15] Others claimed that Hö'elün was impregnated by a ray of light which announced the child's destiny, a legend which echoed that of the mythical ancestor Alan Gua.[16] Yesügei and Hö'elün had three younger sons after Temüjin: Qasar, Hachiun, and Temüge, as well as one daughter, Temülen. The siblings grew up at Yesügei's main camp on the banks of the Onon, where they learned how to ride a horse and shoot a bow; their companions included Behter and his younger full-brother Belgutei, the seven sons of Yesügei's trusted retainer Münglig, and other children of the tribe.[17]

When Temüjin was eight years old, Yesügei decided to betroth him to a suitable girl; he took his heir to the pastures of the prestigious Onggirat tribe, which Hö'elün had been born into, and arranged a marriage between Temüjin and Börte, the daughter of an Onggirat chieftain named Dei Sechen.[18] Accepting this condition, Yesügei requested a meal from a band of Tatars he encountered while riding homewards alone, relying on the steppe tradition of hospitality to strangers. However, the Tatars recognised their old enemy, and slipped poison into his food. Yesügei gradually sickened but managed to return home; close to death, he requested Münglig to retrieve Temüjin from the Onggirat. He died soon after.[19]

Life as matriarch and advisor

Yesügei's death shattered the unity of his people. As Temüjin was only around ten, and Behter around two years older, neither was considered old enough to rule. Led by the widows of Ambaghai, a previous Mongol khan, a Tayichiud faction excluded Hö'elün from the ancestor worship ceremonies which followed a ruler's death and soon abandoned the camp. The Secret History relates that the entire Borjigin clan followed, despite Hö'elün's attempts to shame them into staying with her family.[20] On the other hand, the later Persian historian Rashid al-Din and the Shengwu qinzheng lu, another Chinese chronicle, imply that Yesügei's brothers stood by the widow. It is possible that Hö'elün may have refused to join in levirate marriage with one, or that the author of the Secret History dramatised the situation.[21] All the sources agree that most of Yesügei's people renounced his family in favour of the Tayichiuds and that Hö'elün's family were reduced to a much harsher life.[22] Taking up a traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they collected roots and nuts, hunted for small animals, and caught fish; as the senior widow, Hö'elün was responsible for maintaining the family's wellbeing and internal harmony.[23]

Tensions developed as the children grew older. Both Temüjin and Behter had claims to be their father's heir: although Temüjin was the child of Yesügei's chief wife, Behter was at least two years his senior. There was even the possibility that, as permitted under levirate law, Behter could marry Hö'elün upon attaining his majority and become Temüjin's stepfather.[24] With the friction exacerbated by regular disputes over the division of hunting spoils, Temüjin and his younger brother Qasar ambushed and killed Behter. This taboo act was omitted from the official chronicles but not from the Secret History, which recounts that Hö'elün angrily reprimanded her sons.[25]

When Temüjin married Börte at around the age of fifteen, Hö'elün was gifted a black sable coat, which was immediately used to secure an alliance with Toghrul, khan of the Keraites.[26] Hö'elün would have conceded some responsibilities in the division of labour to her new daughter-in-law—together, they managed the economy and resources of Temüjin's camp, allowing him a foundation from which he could pursue his military campaigns.[27] She was present when Börte and Sochigel were abducted by the Merkits in revenge for Hö'elün's own abduction many years earlier; Börte was retrieved within a year.[28] Hö'elün's advice was highly valued by Temüjin—during his break with Jamuqa, he turned first to her and Börte when uncertain.[29] She also reportedly raised numerous foundlings as half-siblings for her children, although chronological problems seem to indicate that the most famous, Shigi Qutuqu, was in fact raised by Börte.[30]

After Jamuqa defeated Temüjin at Dalan Balzhut in 1187, many of his followers were repulsed by his cruel treatment of Temüjin's followers. These included Münglig and his sons; their earlier abandonment of the family was ignored and they were welcomed to such an extent that Hö'elün was given to Münglig in her third and final marriage.[31] During the difficult following years, when the locations and activities of Temüjin's family are near-completely unknown, it is likely that Hö'elün arranged marriages for her youngest son Temüge and daughter Temülen, in Yesügei's place.[32] Temüjin's 1206 coronation and entitlement as Genghis Khan preceded turmoil in Hö'elün's personal life, as she felt that her rewards undervalued her efforts on behalf of her son; she also likely felt that her husband had been over-compensated.[33] One of Münglig's sons, the shaman Kokechu, also mounted a challenge for Genghis' throne; he managed to divide Genghis from his brothers Qasar and Temüge, whom Hö'elün vigorously defended, before she and Börte convinced Genghis that Kokechu had to be assassinated.[34] The Secret History claims that Hö'elün, worn out by her efforts, died soon after; although some have criticised this as poetical melodrama, nothing more is known of her.[35]

References

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 15; Atwood 2004, p. 456; May 2018, p. 20.

- Broadbridge 2018, pp. 44–45.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 14–15; Broadbridge 2018, p. 45.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 45; May 2018, p. 21.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 47; May 2018.

- Broadbridge 2018, pp. 46–47; May 2018, pp. 21–22.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 45.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 15.

- Broadbridge 2018, pp. 45–46; Ratchnevsky 1991.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 46.

- Atwood 2004, p. 97.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 17–18; Pelliot 1959, pp. 284–287; Morgan 1986, p. 55.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 19.

- Pelliot 1959, pp. 289–291; Man 2004, pp. 67–68; Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 17.

- Brose 2014, § "The Young Temüjin"; Pelliot 1959, p. 288.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 17.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 15–19.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 20–21; Broadbridge 2018, p. 49.

- Ratchnevsky 1991; Broadbridge 2018, pp. 50–51.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 22; May 2018, p. 25; de Rachewiltz 2015, § 71–73.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 22–3; Atwood 2004, pp. 97–98.

- Brose 2014, § "The Young Temüjin"; Atwood 2004, p. 98.

- Broadbridge 2018, pp. 54–55; May 2018, p. 25.

- May 2018, pp. 25–26.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 23–4; de Rachewiltz 2015, §76–78.

- Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 31; Broadbridge 2018, p. 57.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 58.

- May 2018, pp. 29–30; Broadbridge 2018, pp. 58–59.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 64.

- Ratchnevsky 1993, pp. 76–77.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 65.

- Broadbridge 2018, pp. 65–66.

- Broadbridge 2018, p. 69.

- Biran 2012, pp. 44–45; Broadbridge 2018, pp. 69–70.

- Atwood 2004, p. 416; Broadbridge 2018, p. 71.

Sources

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Biran, Michal (2012). Genghis Khan. Makers of the Muslim World. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-204-5.

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1086-3662-9.

- Brose, Michael C. (2014). "Chinggis (Genghis) Khan". In Brown, Kerry (ed.). The Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography. Great Barrington: Berkshire Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-933782-66-9.

- May, Timothy (2018). The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748642373. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctv1kz4g68.11.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection. London: Bantam Press. OCLC 1193945768.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-17563-6.

- Pelliot, Paul (1959). Notes on Marco Polo (PDF). Vol. I. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. OCLC 1741887. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century (Shorter Version; edited by John C. Street). Translated by de Rachewiltz, Igor. 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Translated by Thomas Haining. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-06-31-16785-3.

- Ratchnevsky, Paul (1993). "Sigi Qutuqu (c. 1180–c. 1260)". In de Rachewiltz, Igor (ed.). In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yüan Period (1200-1300). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447033398.