Hollandale, Mississippi

Hollandale is a city in Washington County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 2,323 at the 2020 census.[2]

Hollandale, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| |

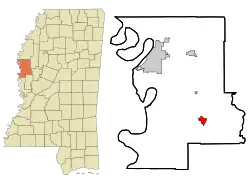

Location of Hollandale, Mississippi | |

Hollandale, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°10′24″N 90°51′19″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Washington |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.22 sq mi (5.74 km2) |

| • Land | 2.22 sq mi (5.74 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 115 ft (35 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,323 |

| • Density | 1,048.29/sq mi (404.83/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 38748 |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-32900 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0671293 |

Deer Creek flows through Hollandale, and the Leroy Percy State Park is west of the city along Mississippi Highway 12. The Hollandale Municipal Airport is northeast of the city.

A 2008 study by the University of North Carolina described Hollandale as "a small community that has been mired in poverty for decades."[3]

History

Hollandale was named for Dr. Holland, the original owner of the town site.[4]

Hollandale was incorporated in 1890, and almost completely destroyed by fire in 1904.[5]

A one-room school house in Hollandale was founded by Emory Peter "E.P." Simmons in 1891. One of the first schools for African-American children in the area, it was used until 1923, when financial support from the Rosenwald Fund enabled the construction of a larger brick school. Simmons worked as an educator and administrator for 52 years, and Simmons High School in Hollandale is named in his honor.[6]

Thomas Roosevelt "T.R." Sanders was a noted community leader. Sanders was principal of Simmons High School for 33 years, and the first superintendent of the Hollandale Colored School District. Sanders developed 'Sanders Estates', the town's first subdivision, and organized an association which provided running water to neighboring Sharkey County. Sanders was the first African-American in Mississippi to receive a master's degree in educational administration.[6][7]

During the Civil Rights Movement, Hollandale was noted for having passed an ordinance forbidding white civil rights workers from living with black citizens.[8]

A marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail dedicated to musician Sam Chatmon is located in Hollandale, as is a marker on the Mississippi Country Music Trail dedicated to Ben Peters.

Hollandale resident Capt. Kermit O. Evans was recognized by the U.S. Congress in 2007 after losing his life in Operation Iraqi Freedom.[9]

The Farm Fresh Catfish processing plant was located in Hollandale until it closed in 2004, laying off 240 workers. The Delta & Pine Land Company of Mississippi, a cotton and soybean producer owned by Monsanto, continues to be a major employer.[3]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 325 | — | |

| 1910 | 481 | 48.0% | |

| 1920 | 799 | 66.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,211 | 51.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,606 | 32.6% | |

| 1950 | 2,346 | 46.1% | |

| 1960 | 2,646 | 12.8% | |

| 1970 | 3,260 | 23.2% | |

| 1980 | 4,336 | 33.0% | |

| 1990 | 3,576 | −17.5% | |

| 2000 | 3,437 | −3.9% | |

| 2010 | 2,702 | −21.4% | |

| 2020 | 2,323 | −14.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 192 | 8.27% |

| Black or African American | 2,068 | 89.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 48 | 2.07% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15 | 0.65% |

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 2,323 people, 802 households, and 513 families residing in the city.

2013 ACS

As of the 2013 American Community Survey, there were 2,695 people living in the city. 87.0% were African American, 12.9% White and 0.1% Native American.

2000 census

As of the census[12] of 2000, there were 3,437 people, 1,104 households, and 803 families living in the city. The population density was 1,536.3 inhabitants per square mile (593.2/km2). There were 1,156 housing units at an average density of 516.7 per square mile (199.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 16.06% White, 83.21% African American, 0.09% Asian, and 0.64% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.76% of the population.

There were 1,104 households, out of which 37.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.9% were married couples living together, 32.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.2% were non-families. 24.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.10 and the average family size was 3.72.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 35.4% under the age of 18, 10.8% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 18.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28 years. For every 100 females, there were 80.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 69.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $20,135, and the median income for a family was $25,313. Males had a median income of $23,194 versus $17,353 for females. The per capita income for the city was $9,251. About 28.4% of families and 38.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 52.7% of those under age 18 and 24.9% of those age 65 or over.

Education

The City of Hollandale is served by the Hollandale School District.

Notable people

- Ruby Andrews, musician.[13]

- Sam Chatmon, musician; moved to Hollandale.[14]

- Andrew DeGraffenreidt, educator and politician; grew up in Hollandale.[15]

- Edward Hill, physician and resident for 27 years; president of American Medical Association.[16]

- Patricia Jessamy, former chief prosecutor for the City of Baltimore, Maryland.[17]

- Martin F. Jue amateur radio products inventor, entrepreneur.[18]

- Ben Peters, Grammy Award-winning musician; grew up in Hollandale.[19]

- Johnny Rembert, professional football player.[20]

- Lavelle White, musician; grew up in Hollandale.[21]

- Ulis Williams, Olympic gold medal winner.[22]

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "United States Census Bureau". Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- Lambe, Will (December 2008). "Small Towns, Big Ideas" (PDF). School of Government, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 158.

- "Blues Locations – Mississippi – Hollandale – Welcome to Earlyblues.com – History Section". Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Landmarks, Legends and Lyrics" (PDF). Greenville and Washington County Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "Death's Elsewhere". Baltimore Sun. September 2, 1998.

- Rucker, Walter C. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313333019.

- Congressional Record, V. 153, PT. 3, February 5, 2007 to February 16, 2007. U.S. Government. 2007. ISBN 9780160869754.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Ruby Andrews". Soulwalking. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "Sam Chatmon - Hollandale". Mississippi Blues Commission. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Congressional Record: Senate: Vol. 155 Part 5. U.S. Government. 2009.

- Peck, Peggy (June 18, 2005). "AMA President-Elect Initially Just Sought Steady Work". CNN.

- "PATRICIA COATS JESSAMY". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Coy, Steve (March 27, 2012). "How I Started MFJ and Its Very Early Days". Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- "Ben Peters - Hollandale". Mississippi Country Music Trail. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "Johnny Rembert". Sports Reference. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Bays, Kenneth (September 2012). "Soulful Sounds" (PDF). Memorial.

- "Ulis Williams". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2013.