Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was Holy Roman Emperor from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of the Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

| Otto III | |

|---|---|

Otto III from the Gospels of Otto III | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 21 May 996 – 23 January 1002 |

| Predecessor | Otto II |

| Successor | Henry II |

| King of Italy | |

| Reign | 12 April 996 – 23 January 1002 |

| Predecessor | Otto II |

| Successor | Arduin of Ivrea |

| King of Germany | |

| Reign | 25 December 983 – 23 January 1002 |

| Coronation | 983 |

| Predecessor | Otto II |

| Successor | Henry II |

| Regent |

|

| Born | June/July 980 Klever Reichswald near Kessel, Kingdom of Germany |

| Died | 23 January 1002 (aged 21) Faleria, Papal States |

| Burial | |

| House | Ottonian |

| Father | Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Theophanu |

Otto III was crowned as King of Germany in 983 at the age of three, shortly after his father's death in Southern Italy while campaigning against the Byzantine Empire and the Emirate of Sicily. Though the nominal ruler of Germany, Otto III's minor status ensured his various regents held power over the Empire. His cousin Henry II, Duke of Bavaria, initially claimed regency over the young king and attempted to seize the throne for himself in 984. When his rebellion failed to gain the support of Germany's aristocracy, Henry II was forced to abandon his claims to the throne and to allow Otto III's mother Theophanu to serve as regent until her death in 991. Otto III was then still a child, so his grandmother, Adelaide of Italy, served as regent until 994.

In 996, Otto III marched to Italy to claim the titles of King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor, which had been left unclaimed since the death of Otto II in 983. Otto III also sought to reestablish Imperial control over the city of Rome, which had revolted under the leadership of Crescentius II, and through it the papacy. Crowned as emperor, Otto III put down the Roman rebellion and installed his cousin as Pope Gregory V, the first Pope of German descent. After the Emperor had pardoned him and left the city, Crescentius II again rebelled, deposing Gregory V and installing John XVI as Pope. Otto III returned to the city in 998, reinstalled Gregory V, and executed both Crescentius II and John XVI. When Gregory V died in 999, Otto III installed Sylvester II as the new pope. Otto III's actions throughout his life further strengthened imperial control over the Catholic Church.

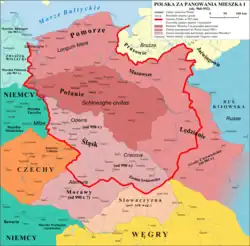

From the beginning of his reign, Otto III faced opposition from the Slavs along the eastern frontier. Following the death of his father in 983, the Slavs rebelled against imperial control, forcing the Empire to abandon its territories east of the Elbe river. Otto III fought to regain the Empire's lost territories throughout his reign with only limited success. While in the east, Otto III strengthened the Empire's relations with Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary. Through his affairs in Eastern Europe in 1000, he was able to extend the influence of Christianity by supporting mission work in Poland and through the crowning of Stephen I as the first Christian king of Hungary.

Returning to Rome in 1001, Otto faced a rebellion by the Roman aristocracy, which forced him to flee the city. While marching to reclaim the city in 1002, Otto suffered a sudden fever and died in Castle Paterno in Faleria at the age of 21. With no clear heir to succeed him, his early death threw the Empire into political crisis.

Otto was a charismatic figure associated with several legends and notable figures of his time. Opinions on Otto III and his reign vary considerably. Recognized in his own day as a brilliant, energetic, pious leader, Otto was portrayed by nineteenth century historians as a whimsical, overidealistic dreamer who failed in his duty towards Germany. Modern historians generally see him in a positive light, but several facets of the emperor remain enigmatic and debates on the true intentions behind his Imperial Renovation (renovatio imperii Romanorum) program continue.

Early life

Otto III was born in June or July 980 somewhere between Aachen and Nijmegen, in modern-day North Rhine-Westphalia. The only son of Emperor Otto II and Empress Theophanu, Otto III was the youngest of the couple's four children. Immediately prior to Otto III's birth, his father had completed military campaigns in France against King Lothar.

On 14 July 982, Otto II's army suffered a crushing defeat against the Muslim Emirate of Sicily at the Battle of Stilo. Otto II had been campaigning in Southern Italy with hopes of annexing the whole of Italy into the Holy Roman Empire. Otto II himself escaped the battle unharmed but many important imperial officials were among the battle's casualties. Following the defeat and at the insistence of the Empire's nobles, Otto II called an assembly of the Imperial Diet in Verona at Pentecost, 983, where he proposed to the assembly to have the three-year-old Otto III elected as king of Germany and Italy, becoming Otto II's undoubted heir apparent. This was the first time a German ruler had been elected on Italian soil. After the assembly was concluded, Otto III traveled across the Alps in order to be crowned at Aachen, the traditional location of the coronation of the German kings. Otto II stayed behind to address military action against the Muslims. While still in central Italy, however, Otto II suddenly died on 7 December 983, and was buried in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Otto III was crowned as king on Christmas Day 983, three weeks after his father's death, by Willigis, the Archbishop of Mainz, and by John X, the Archbishop of Ravenna.[1] News of Otto II's death first reached Germany shortly after his son's coronation.[1] The unresolved problems in southern Italy and the Slavic uprising on the Empire's eastern border made the Empire's political situation extremely unstable. With a minor on the throne, the Empire was thrown into confusion and Otto III's mother Theophanu assumed the role of regent for her young son.[2]

Child King

Regency of Henry II

Otto III's cousin Henry II had been deposed as Duke of Bavaria by Otto II in 976 following his failed rebellion and imprisoned within the Bishopric of Utrecht. Following Otto II's death, Henry was released from prison. As Otto III's nearest male Ottonian relative, Henry II claimed the regency over his infant cousin.[2] Archbishop of Cologne Warin granted Henry II the regency without substantial opposition. Only Otto III's mother Theophanu objected, along with his grandmother, the Dowager Empress Adelaide of Italy, and his aunt, Abbess Matilda of Quedlinburg. Adelaide and Matilda, however, were both in Italy and unable to press their objections.

As regent, Henry II took actions aimed less at guardianship of his infant cousin and more at claiming the throne for himself. According to Gerbert of Aurillac, Henry II adopted a Byzantine-style joint-kingship. Towards the end of 984, Henry II sought to form alliances between himself and other important figures in the Ottonian world, chief among them his cousin King Lothar of France. In exchange for Lothar's agreement to make Henry II king of Germany, Henry II agreed to relinquish Lotharingia to Lothar.[3] The two agreed to join their armies on 1 February 985, in order to take the city of Breisach, but at the last minute, Henry's resolve weakened. Nevertheless, Lothair continued to campaign into German lands and succeeded in overrunning the Verdun by March 985.[4]

Henry II took the young Otto III and traveled to Saxony. There, Henry II invited all the great nobles of the kingdom to celebrate Palm Sunday at Magdeburg for 985. He then campaigned openly for his claim to the German throne, with limited success. Among those who supported his claims were Duke Mieszko I of Poland and Duke Boleslaus II of Bohemia.[3] Henry II was also supported by Archbishop Egbert of Trier, Archbishop Gisilher of Magdeburg, and Bishop Dietrich I of Metz.[3]

Those who opposed Henry II's claims fled to Quedlinburg in Saxony to conspire against him. When he became aware of this conspiracy, he moved his army towards Quedlinburg in hopes of crushing his opposition. Henry II sent Folcmar, the Bishop of Utrecht, ahead of him in order to attempt a peace negotiation between him and the conspirators. The negotiations failed when the conspirators refused to swear allegiance to anyone other than Otto III, with Bernard I, Duke of Saxony, maintaining allegiance to the child king. In response to his failure to gain control over Saxony, Henry II promised to hold future peace negotiations and then headed for the Duchy of Bavaria. With his long-standing familial ties in the region, many bishops and counts recognized him as the rightful heir to the throne. Henry III, Duke of Bavaria, who had been installed as Duke by Otto II, refused to recognize Henry II and remained loyal to Otto III.

With his successes and failures in Saxony and Bavaria, Henry II's claims depended on gaining support in the Duchy of Franconia, which was a direct possession of the German kings. The Franconian nobles, led by Archbishop Willigis of Mainz (the Primate of Germany) and Conrad I, Duke of Swabia, refused to abandon Otto III.[2] Fearing outright civil war, Henry II relinquished Otto III to the joint-regency of his mother and grandmother on 29 June 985.[3] In return for his submission, Henry II was restored as the Duke of Bavaria, replacing Henry III who became the new Duke of Carinthia.[5]

Regency of Theophanu

The regency of Theophanu, from 984 until her death in 991, was largely spared internal revolt. She struggled throughout to reinstate the Diocese of Merseburg, which her husband Otto II had absorbed into the Archdiocese of Magdeburg in 981. Theophanu also retained Otto II's court chaplains, in particular Count Bernward of Hildesheim and Archbishop Willigis, who, as the Archbishop of Mainz, was ex officio the secular Archchancellor of Germany. Though Theophanu was regent, Willigis was given considerable leeway in administering the kingdom. One of the Empress's greatest achievements was her success in maintaining German supremacy over Bohemia, as Boleslaus II, Duke of Bohemia, was forced to accept the authority of Otto III.[5]

In 986 the five-year-old Otto III celebrated Easter at Quedlinburg. The four major dukes of Germany (Henry II of Bavaria, Conrad I of Swabia, Henry III of Carinthia, and Bernard I of Saxony) also paid tribute to the child king. Imitating similar ceremonies carried out under Otto I in 936 and Otto II in 961, the dukes served Otto III as his ceremonial steward, chamberlain, cupbearer, and marshal, respectively. This service symbolized the loyalty of the dukes to Otto III and their willingness to serve him. Most significant was the submission of Henry II, who demonstrated his loyalty to his cousin despite his failed rebellion two years earlier. The next year, from the age of six onward, Otto III would receive education and training from Bernward of Hildesheim and Gerbert d'Aurillac.

During the regency of Theophanu, the Great Gandersheim Conflict broke out, concerning control of Gandersheim Abbey and its estates. Both the Archbishop of Mainz and the Bishop of Hildesheim claimed authority over the abbey, including the authority to anoint the abbey's nuns. The conflict began in 989 when Otto III's older sister Sophia became a nun in the abbey. Sophia refused to accept the authority of the Bishop of Hildesheim, instead recognizing only that of the Archbishop of Mainz. The conflict escalated until it was brought before the royal court of Otto III and Theophanu. The royal intervention eased the tensions between the parties by providing that both bishops would anoint Sophia, while anointing the remaining nuns of the abbey would be left to the Bishop of Hildesheim alone.

In 989 Theophanu and Otto III made a royal expedition to Italy to visit the grave of Otto II in Rome. After crossing the Alps and reaching Pavia in northern Italy, the Empress had her longtime confidant John Philagathos appointed as Archbishop of Piacenza. After a year in Italy, the royal court returned to Germany, where Theophanu died in Nijmegen on 15 June 991, at the age of 31. She was buried in the Church of St. Pantaleon in Cologne.

Because Otto III was still a child (only eleven when his mother died), his grandmother, the Dowager Empress Adelaide of Italy, became regent, together with Archbishop Willigis of Mainz, until he became old enough to rule on his own in 994.[6]

Independent reign

As Otto III grew in age, the authority of his grandmother gradually waned until 994 when Otto III reached the age of 14. At an assembly of the Imperial Diet held in Solingen in September 994, Otto III was granted the ability to fully govern the kingdom without the need of a regent. With this, Adelaide retired to a nunnery she had founded at Selz in Alsace. Although she never became a nun, she spent the rest of her days there in the service of the Church and in acts of charity. As Otto III was still unmarried, from 995 until 997 his older sister Sophia accompanied him and acted as his consort.

One of Otto III's first actions as an independent ruler was to appoint Heribert of Cologne as his chancellor over Italy, a position he would hold until Otto's death in 1002. Otto III followed in his grandfather Otto I's footsteps in the beginning of his reign,[7] by appointing a new pope, Gregory V, and leaving Rome. Gregory V was expelled and Otto III returned to Rome in 998 where he stayed permanently until his death.[7] In the summer of 995, Otto sent the Archbishop of Piacenza, John Philagathos, to Constantinople as his representative to arrange a marriage between himself and a Byzantine princess following the example of his father, Otto II, who solidified his claim to the throne by marrying the Byzantine Theophanu. For a while the discussions were about Zoe Porphyrogenita.

War against the Slavs

The Lutici federation of West Slavic Polabian tribes had remained quiet during the early years of Otto III's reign, even during Henry II's failed rebellion. In 983, following Otto II's defeat at the battle of Stilo, the Slavs revolted against Imperial control, forcing the Empire to abandon its territories east of the Elbe River in the Northern March and the Billung March.[8] With the process of Christianization halted, the Slavs left the Empire in peace, and with Henry II's rebellion put down, Theophanu launched multiple campaigns to re-conquer the lost eastern territories, beginning in 985. Even though he was only six at the time, Otto III personally participated in these campaigns. During the expedition of 986 against the Slavs, Otto III received the homage of Duke Mieszko I of Poland, who provided the Imperial army with military assistance and gave Otto III a camel.[5] Although the Lutici were subdued for a time in 987, they continued to occupy the young king's attention.

In September 991, when Otto III was eleven, Slavonic raiders captured the city of Brandenburg. In 992 this invasion, as well as an incursion of Viking raiders, forced Otto III to lead his army against the invaders, and he suffered a crushing defeat in this campaign.[9] The next year, Germany suffered an outbreak of famine and pestilence. In 994 and 995, Otto III led fruitless campaigns against the northern Slavs and the Vikings,[9] but he did successfully re-conquer Brandenburg in 993, and in 995 he subdued the Obotrite Slavs.[9]

In the fall of 995, after Otto III reached his majority, he again took to the field against the Lutici, this time aided by the Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave.[10] Then in 997 he had to deal with a new Lutician attack on Arneburg on the Elbe, which they managed to retake for a short while.[10]

Reign as emperor

.jpg.webp)

Roman instability

Prior to his sudden death in December 983, Otto II had installed Pietro Canepanova as pope. Calling himself Pope John XIV, Canepanova was a non-Roman from Lombardy who had served as Otto II's chancellor in Italy. After Otto II's death, John XIV intervened in the dispute between Henry II of Bavaria and Theophanu over the regency, issuing an edict ordering Henry to turn Otto over to his mother.

During that turmoil, the Roman aristocracy saw an opportunity to remove the non-Roman John XIV and install a pope from among themselves. The Antipope Boniface VII, who had spent nine years in exile in the Byzantine Empire, joined forces with Byzantine nobles in southern Italy and marched on Rome in April 984 in order to claim the papal throne for himself. With the aid of the sons of Crescentius the Elder — Crescentius II and John Crescentius — Boniface VII was able to imprison John XIV in the Tomb of Hadrian. Four months later, on 20 August 984, John XIV died in his prison, either starved or poisoned, probably on the orders of Boniface.[11]

With Otto's regency seated in Germany, Crescentius II took the title of Patricius Romanorum (Patrician of the Romans) and became the effective ruler of Rome, although he did not act entirely independently of central authority, presenting himself as a lieutenant of the king. When Boniface VII died in 985, Pope John XV was chosen to succeed him. Although the details of the election are unknown, it is likely that Crescentius II played a key role in the process. For a number of years, Crescentius II exercised authority over the city, severely limiting the autonomy of the pope in the process. When the Empress Theophanu was in Rome between 989 and 991, Crescentius II nominally subordinated himself to her, though he maintained his position as ruler of the city.[12]

First expedition into Italy

2.JPG.webp)

After taking the crown in 994, Otto III faced first a Slavic rebellion, which he put down, and then an attempt by Crescentius II to seize power in Italy.

When Otto III turned his attention to Italy,[10] he not only intended to be crowned Emperor but also to come to the aid of Pope John XV, who had been forced to flee Rome. Otto set out for Italy from Ratisbon in March 996. In Verona, he became the patron of Otto Orseolo, the son of Venetian Doge Pietro II Orseolo. He then pledged to support Otto Orseolo as the next Doge of Venice, leading to a period of good relations between the Holy Roman Empire and the Republic of Venice after years of conflict under Otto II.

Reaching Pavia for Easter, 996, Otto III was declared King of Italy and crowned with the Iron Crown of the Lombards.[12] The king failed, however, to reach Rome before Pope John XV died of fever.[13] While Otto III was in Pavia, Crescentius II, fearing the king's march on Rome, reconciled with Otto III and agreed to accept his nominee as pope.[12]

While in Ravenna, Otto III nominated his cousin and court chaplain Bruno, who was then only twenty-three years old, and sent him to Rome with Archbishop Willigis to secure the city. In early May 996, Bruno was consecrated as Gregory V, the first pope of German nationality.[14] Despite submitting to Otto III, Crescentius shut himself in his family's stronghold, the Tomb of Hadrian, out of fear of retribution.[15]

The new supreme pontiff crowned Otto III as emperor on 21 May 996, in Rome at St. Peter's Basilica. The Emperor and Pope then held a synod at St. Peter's on 25 May to serve as the Empire's highest judicial court. The Roman nobles who had rebelled against Pope John XV were summoned before the synod to give an account of their actions. A number of the rebels, including Crescentius II, were banished for their crimes. Pope Gregory V, however, wished to inaugurate his papal reign with acts of mercy and pleaded for clemency from the Emperor, who issued pardons to those he convicted. In particular, while Crescentius II was pardoned by Otto III, he was deprived of his title of Patricius but was permitted to live out his life in retirement at Rome.[16]

Following the synod, Otto III appointed Gerbert of Aurillac, the Archbishop of Reims, to be his tutor.[10] Counseled by Gerbert and Bishop Adalbert of Prague,[17] Otto III set out to reorganize the Empire. Influenced by the ruin of ancient Rome and perhaps by his Byzantine mother,[16] Otto III dreamed of restoring the glory and power of the Roman Empire, with himself at the head of a theocratic state.[10] He also introduced some Byzantine court customs.[18] To shore up his power in Italy, Otto III sought the support of existing Italian religious communities. For instance, he granted royal immunity to the Abbey of San Salvatore, a rich monastery along the shores of the Lago di Bientina in Tuscany.

Through the election of Gregory V, Otto III exercised greater control over the Church than his grandfather Otto I had decades earlier. The Emperor quickly demonstrated his intention to withdraw Imperial support for the privileges of the Holy See laid out by Otto I. Under the Diploma Ottonianum issued by Otto I, the Emperor could only veto papal candidates. Otto III, however, had nominated and successfully installed his own candidate. The Emperor also refused to acknowledge the Donation of Constantine, which Otto III declared a forgery.[18] Under a decree supposedly issued by Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, the Pope was granted secular authority over western Europe. These actions resulted in increased tensions between the Roman nobility and the Church, who had traditionally reserved the right to name the pope from among their own members.[18]

After his coronation, Otto III returned to Germany in December 996, staying along the Lower Rhine (especially in Aachen) until April 997. His specific activities during this time are not known. In summer 997, Otto III campaigned against the Elbe Slavs in order to secure Saxony's eastern border.

Second expedition into Italy

When Otto III left Italy for Germany, the situation in Rome remained uncertain. In September 996, a few months after receiving a pardon from Otto III, Crescentius II met with the Archbishop of Piacenza, John Philagathos, a former adviser to the late Empress Theophanu, to devise a plan to depose the newly installed Pope Gregory V. In 997, with the active support of Byzantine Emperor Basil II, Crescentius II led a revolt against Gregory V, deposed him, and installed John Philagathos as Pope John XVI, an antipope, in April 997.[19] Gregory fled to Pavia in northern Italy, held a synod, and excommunicated John. The new bishop of Piacenza, Siegfried, came north to meet Otto at Eschwege in July.[20] Otto detached the city from the county of Piacenza and granted it to the bishop in perpetuity.[21]

Putting down the Slavic forces in eastern Saxony, Otto III began his second expedition into Italy in December 997. Accompanied by his sister Sophia into Italy, Otto III named his aunt Matilda, Abbess of Quedlinburg, as his regent in Germany,[22] becoming the first non-duke or bishop to serve in that capacity. Otto III peacefully retook Rome in February 998 when the Roman aristocracy agreed to a peace settlement. With Otto III in control of the city, Gregory V was reinstated as pope.[23] John XVI fled, but the Emperor's troops pursued and captured him, cut off his nose and ears, cut out his tongue, broke his fingers, blinded him, and then brought him before Otto III and Gregory V for judgement. At the intercession of Saint Nilus the Younger, one of his countrymen, Otto III spared John XVI's life and sent him to a monastery in Germany, where he would die in 1001.

Crescentius II retreated again to the Tomb of Hadrian, the traditional stronghold of the Crescentii, and was then besieged by Otto III's imperial army. Towards the end of April, the stronghold was breached, and Crescentius II was taken prisoner and executed by decapitation. His body was put on public display at Monte Mario.

Reign from Rome

Otto III made Rome the administrative capital of his Empire and revived elaborate Roman customs and Byzantine court ceremonies. During his time in Italy, the Emperor and the Pope attempted to reform the Church, and confiscated church property was returned to the respective religious institutions. Additionally, after the death of the Bishop of Halberstadt in November 996, who had been one of the masterminds behind the abolition of the bishopric of Merseburg, Otto III and Pope Gregory V began the process of reviving the Diocese. Otto I had established the Diocese in 968 following his victory over the Hungarians in order to Christianize the Polabian Slavs but it had been effectively destroyed in 983 with the Great Slav Rising following the death of Otto II that year.

Otto III arranged for his imperial palace to be built on the Palatine Hill[18] and planned to restore the ancient Roman Senate to its position of prominence. He revived the city's ancient governmental system, including appointing a City Patrician, a City Prefect, and a body of judges whom he commanded to recognize only Roman law.[24] In order to strengthen his title to the Roman Empire and to announce his position as the protector of Christendom, Otto III took for himself the titles "the Servant of Jesus Christ," "the Servant of the Apostles",[18] "Consul of the Senate and People of Rome," and "Emperor of the World".

Between 998 and 1000, Otto III made several pilgrimages. In 999, he made a pilgrimage from Gargano to Benevento, where he met with the hermit monk Romuald and the Abbot Nilus the Younger (at that time a highly venerated religious figure) in order to atone for executing Crescentius II after promising his safety.[23] During this particular pilgrimage, his cousin Pope Gregory V died in Rome after a brief illness. Upon learning of Gregory V's death, Otto III installed his long-time tutor Gerbert of Aurillac as Pope Sylvester II.[23] The use of this papal name was not without cause: it recalled the first pope of this name, who had allegedly created the "Christian Empire" together with Emperor Constantine the Great.[10] This was part of Otto III's campaign to further link himself with both the Roman Empire and the Church.

Like his grandfather before him, Otto III strongly aspired to be the successor of Charlemagne. In 1000, he visited Charlemagne's tomb in Aachen, removing relics from it and transporting them to Rome. Otto III also carried back parts of the body of Bishop Adalbert of Prague, which he placed in the church of San Bartolomeo all'Isola he had built on the Tiber Island in Rome. Otto III also added the skin of Saint Bartholomew to the relics housed there.

Affairs in Eastern Europe

Polish relations

.jpg.webp)

Around 960, the Polish Piast dynasty under Mieszko I had extended the Duchy of Poland beyond the Oder River in an effort to conquer the Polabian Slavs, who lived along the Elbe River. This brought the Polans into Germany's sphere of influence and into conflict with Otto I's Kingdom of Germany, who also desired to conquer the Polabian Slavs. Otto I sent his trusted lieutenant, the Saxon Margrave Gero, to address the Polan threat, while Otto I traveled to Italy to be crowned as emperor. Gero defeated Mieszko I in 963 and forced him to recognize Otto I as his overlord.[25] In return for submitting tribute to the newly crowned Emperor, Otto I granted Mieszko I the title of amicus imperatoris ("Friend of the Emperor") and acknowledged his position as dux Poloniae ("Duke of Poland").

Mieszko I remained a powerful ally of Otto I for the remainder of his life. He strengthened his alliance with the Empire by marrying Oda, the daughter of the Saxon Margrave Dietrich of Haldensleben, in 978 and by marrying his son Bolesław I to a daughter of Margrave Rikdag of Meissen. Mieszko I, then a pagan, would marry the Christian daughter of Boleslaus I, Dobrawa, in 965 and would convert to Christianity in 966, bringing Poland closer to the Christian states of Bohemia and the Empire. Following the death of Otto I in 973, Mieszko I sided with Henry II, Duke of Bavaria, against Otto II during Henry's failed revolt in 977. After the revolt was put down, Mieszko I swore loyalty to Otto II.[26] When Otto II died suddenly in 983 and was succeeded by the three-year old Otto III, Mieszko I again supported Henry II in his bid for the German throne.[3] When Henry's revolt failed, Mieszko I swore loyalty to Otto III.

Mieszko I's son Bolesław I succeeded him as Duke in 992, and Poland continued its alliance with the Empire. Polish forces joined the Empire's campaigns to put down the Great Slav Rising, led by the Polabian Lutici tribes during the 980s and 990s.

Bohemian relations

Germany and the Duchy of Bohemia came into significant contact with one another in 929, when German King Henry I had invaded the Duchy to force Duke Wenceslaus I to pay regular tribute to Germany. When Wenceslaus I was assassinated in 935, his brother Boleslaus I succeeded him as Duke and refused to continue paying the annual tribute to Germany. This action caused Henry I's son and successor Otto I to launch an invasion of Bohemia. Following the initial invasion, the conflict deteriorated into a series of border raids that lasted until 950 when Otto I and Boleslaus I signed a peace treaty. Boleslaus I agreed to resume paying tribute and to recognize Otto I as his overlord. The Duchy was then incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire as a constituent state.

Bohemia would be a major factor in the many battles along the Empire's eastern border. Boleslaus I helped Otto I crush an uprising of Slavs along the Lower Elbe in 953, and they joined forces again to defeat the Hungarians at the battle of Lechfeld in 955. In 973 Otto I established the bishopric of Prague, subordinated to the archbishopric of Mainz, in order to Christianize the Czech territory. To strengthen the Bohemian-Polish alliance, Boleslaus I's daughter Dobrawa was married to the pagan Mieszko I of Poland in 965. The marriage helped bring Christianity to Poland. He died in 972 and was succeeded as Duke by his oldest son Boleslaus II.

After initially siding with Henry II against Otto II during Henry's failed revolt in 977, Boleslaus II swore loyalty to Otto II.[27] When Otto II died suddenly in 983 and was succeeded by the three-year old Otto III, Boleslaus II again supported Henry II in his bid for the German throne.[3] As in 977, Henry's bid failed, and Boleslaus II swore loyalty to Otto III.

Hungarian relations

Otto I's defeat of the Hungarians at Lechfeld in 955 ended the decades-long Hungarian invasions of Europe. The Hungarian Grand Prince Fajsz was deposed following the defeat and was succeeded by Taksony, who adopted the policy of isolation from the West. He was succeeded by his son Géza in 972, who sent envoys to Otto I in 973.[28] Géza was baptised in 972, and Christianity spread among the Hungarians during his reign.[29]

Géza expanded his rule over the territories west of the Danube and the Garam, but significant parts of the Carpathian Basin still remained under the rule of local tribal leaders.[30] In 997, Géza died and was succeeded by Stephen (originally called Vajk). Stephen was baptized by Bishop Adalbert of Prague and married Gisela, daughter of Henry II and distant niece of Otto III.[31] Stephen had to face the rebellion of his relative, Koppány, who claimed Géza's inheritance based on the Hungarian tradition of agnatic seniority.[32] Stephen defeated Koppány using some Western tactics and a small number of Swabian knights.

When Otto III traveled to Poland in 1000, he brought with him a crown from Pope Sylvester II. With Otto III's approval, Stephen was crowned as the first Christian king of Hungary on Christmas Day, 1000.[33]

Congress of Gniezno

In 996, Duke Bolesław I of Poland sent the longtime Bishop of Prague, Adalbert, to Christianize the Old Prussians. He was martyred by the Prussians for his efforts in 997.[34] Bolesław I, who had bought Adalbert's body from the Old Prussians for its weight in gold, had Adalbert laid to rest in the cathedral at Gniezno, which eventually became the ecclesiastical center of Poland. Otto III and Bolesław I worked together to canonize Adalbert, making him the first Slavic bishop to become a saint.[35] In December 999, Otto III left Italy to make a pilgrimage from Rome to Gniezno in Poland to pray at the grave of Adalbert.[35]

Otto III's pilgrimage allowed the Emperor to extend the influence of Christianity in Eastern Europe and to strengthen relations with Poland and Hungary by naming them federati ("allies").[36] On the pilgrimage to Gniezno, the Emperor was received by Bolesław I at the Polish border on the Bobr River near Małomice. Between 7 and 15 March 1000, Otto III invested Bolesław I with the titles frater et cooperator Imperii ("Brother and Partner of the Empire") and populi Romani amicus et socius ("Friend and ally of Rome").[36] Otto III gave Bolesław a replica of his Holy Lance (part of the Imperial Regalia) and Bolesław presented the Emperor with a relic, an arm of Saint Adalbert in exchange.

On the same foreign visit, Otto III raised Gniezno to the rank of an archbishopric and installed Radzim Gaudenty, a brother of Saint Adalbert, as its first archbishop.[35] Otto III also established three new subordinate dioceses under the Archbishop of Gniezno: the Bishopric of Kraków (assigned to Bishop Poppo), the Bishopric of Wrocław (assigned to Bishop Jan), and the Bishopric of Kołobrzeg in Pomerania (assigned to Bishop Reinbern).[35]

Bolesław I subsequently accompanied Otto III on his way back to Germany. Both proceeded to the grave of Charlemagne at Aachen Cathedral, where Bolesław received Charlemagne's throne as a gift. Both arranged the betrothal of Bolesław's son Mieszko II Lambert with the Emperor's niece Richeza of Lotharingia.

Final years

Return to Rome

The Emperor spent the remainder of 1000 in Italy without any notable activities. In 1001, the people of the Italian city of Tibur revolted against Imperial authority. Otto III besieged the city and put down the revolt with ease, sparing its inhabitants. This action angered the people of Rome, who viewed Tibur as a rival and wanted the city destroyed.[37] In a change of policy towards the papacy, Otto III bestowed the governance of the city upon Pope Sylvester II as part of the Papal States but under the overlordship of the Holy Roman Empire. Previously, Otto III had revoked the Pope's rights as secular ruler by denying the Donation of Constantine and by amending the Diploma Ottonianum.

In the weeks after Otto's actions at Tibur, the Roman people rebelled against their Emperor, led by Count Gregory I of Tusculum. The rebellious citizens besieged the Emperor in his palace on the Palatine Hill and drove him from the city.[23] Accompanied by Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim and the German chronicler Thangmar, he returned to the city to conduct peace negotiations with the rebellious Romans. Though both sides agreed to a peaceful settlement, with the Romans respecting Otto's rule over the city, feelings of mistrust remained. The Emperor's advisors urged him to wait outside the city until military reinforcements could arrive to ensure his safety.

Emperor Otto, accompanied by Pope Sylvester II, traveled to Ravenna to do penance in the monastery of Sant'Apollinare in Classe and to summon his army. While in Ravenna, he received ambassadors from Duke Bolesław I of Poland and approved the plans of King Stephen of Hungary to establish the Archdiocese of Esztergom in order to convert Hungary to Christianity. The Emperor also strengthened relations with the Venetian Doge, Pietro II Orseolo. Since 996, Otto had been godfather to Pietro II's son, Otto Orseolo, and in 1001 he arranged for Pietro II's daughter to be baptized.

Death

After summoning his army in late 1001, Otto headed south to Rome to ensure his rule over the city. During the travel south, however, he suffered a sudden and severe fever. He died in a castle near Civita Castellana on 24 January 1002.[38] He was 21 years old and had reigned as an independent ruler for just under six years, having nominally reigned for nearly nineteen. The Byzantine princess Zoe, second daughter of the Emperor Constantine VIII, had just disembarked in Apulia on her way to marry him.[39] Otto III's death has been attributed to various causes. Medieval sources speak of malaria, which he had caught in the unhealthy marshes that surrounded Ravenna.[23] Following his death, the Roman people suggested that Stefania, the widow of Crescentius II, had made Otto fall in love with her and then poisoned him.

The Emperor's body was carried back to Germany by his soldiers, as his route was lined with Italians who hurled abuses at his remains.[33] He was buried in Aachen Cathedral alongside the body of Charlemagne.[40]

Succession crisis

Otto III, having never married, died without issue, leaving the Empire without a clear successor.[41] As the funeral procession moved through the Duchy of Bavaria in February 1002, Otto III's cousin duke Henry IV of Bavaria (son of Henry the Quarrelsome, representing the Bavarian-Liudolfing line) asked the bishops and nobles to elect him as the new king of Germany.[41] With the exception of the Bishop of Augsburg and Willigis (Archbishop and Elector of Mainz),[41] Henry II received no support for his claims. To emphasise Henry's claim to the throne the Bishop of Augsburg even buried Otto's intestines in the Cathedral of Augsburg in order to show that Henry cared for the well-being of Otto's body. At Otto III's funeral on Easter 1002, in Aachen, the German nobles repeated their opposition to Henry II. Several rival candidates for the throne – Count Ezzo of Lotharingia, Margrave Eckard I of Meissen,[41] and Duke Herman II of Swabia (a Conradine)[41] — strongly contested the succession of Henry II.[41] On 6 or 7 June 1002 in Mainz, the duke of Bavaria was elected King of the Romans as Henry II by his Bavarian, Frankish and upper Lotharingian supporters, and anointed and crowned king by Willigis.[41] In the meantime, Ekkehard had already been killed in a feud unconnected to the succession dispute.[41] Henry then launched an indecisive campaign against Herman of Swabia, but was recognised by the Thuringians, Saxons and lower Lotharingians in subsequent months, either by homage or renewed election.[42] On 1 October 1002 in Bruchsal, Herman finally submitted to Henry II, and the war of succession was over.[43]

Without an Emperor on the throne, Italy began to break away from German control. On 15 February 1002, the Lombard Margrave of Ivrea Arduin, an opponent of the Ottonian dynasty, was elected King of Italy in Pavia.[43]

Character

Otto's mental gifts were considerable, and were carefully cultivated by Bernward, later bishop of Hildesheim, and Gerbert of Aurillac, archbishop of Reims.[6] He spoke three languages and was so learned that contemporaries called him mirabilia mundi or "the wonder of the world" (later, Frederick II would often be referred to as stupor mundi, also translated into English as "the wonder of the world."[22] The two emperors are often compared on account of their intellectual power, ambitions and connection to the Italian culture).[44] Enamoured as he was of Greek and Roman culture, a speech was attributed to him in Thangmar's Vita Bernwardi saying he preferred Romans to his German subjects though the speech's authenticity is disputed.[45]

Accounts of his reign

Between 1012 and 1018 Thietmar of Merseburg wrote a Chronicon, or Chronicle, of eight books dealing with the period between 908 and 1018. For the earlier part he used Widukind's Res gestae Saxonicae, the Annales Quedlinburgenses and other sources; the latter part is the result of personal knowledge. The chronicle is nevertheless an excellent authority for the history of Saxony during the reigns of the emperors Otto III and Henry II. No kind of information is excluded, but the fullest details refer to the bishopric of Merseburg and to the wars against the Wends and the Poles.

Family

| German royal dynasties | |

|---|---|

| Ottonian dynasty | |

Chronology | |

| Henry I | 919 – 936 |

| Otto I | 936 – 973 |

| Otto II | 973 – 983 |

| Otto III | 983 – 1002 |

| Henry II | 1002 – 1024 |

Family | |

| Ottonian dynasty family tree Family tree of the German monarchs Category:Ottonian dynasty | |

Succession | |

| Preceded by Conradine dynasty | |

| Followed by Salian dynasty | |

Otto III was a member of the Ottonian dynasty of kings and emperors who ruled the Holy Roman Empire (previously Germany) from 919 to 1024. In relation to the other members of his dynasty, Otto III was the great-grandson of Henry the Fowler, grandson of Otto I, son of Otto II, and a second-cousin to Henry II.

Otto III never married and never fathered any children due to his early death. At the time of his death, the Byzantine princess Zoë Porphyrogenita, second daughter of Emperor Constantine VIII, was traveling to Italy to marry him.[39]

References

- Duckett, pg. 106

- Comyn, pg. 121

- Duckett, pg. 107

- Duckett, pgs. 107-108

- Duckett, pg. 108

- Comyn, pg. 122

- Wickham, C. (2011). Rethinking Otto III -- or Not. History Today, 61(2), 72

- Reuter, pg. 256

- Duckett, pg. 109

- Reuter, pg. 257

- Eleanor Shipley Duckett, Death and Life in the Tenth Century (University of Michigan Press, 1967), p. 110

- Duckett, pg. 111

- Comyn, pg. 123

- Duckett, pg. 111; Reuter, pg. 258

- Comyn, pg. 124

- Duckett, pg. 112

- Duckett, pg. 113

- Reuter, pg. 258

- Duckett, pg. 124

- Moehs 1972, pp. 57–58.

- Longhena et al. 1935.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Comyn, pg. 125

- Bryce 1904, p. 146.

- Reuter, 164. Howorth, 226.

- Duckett, pg. 101

- Comyn, pg. 117

- Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 25, 28.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 28.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 30.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 32.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 35.

- Comyn, pg. 126

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Janine Boßmann, Otto III. Und der Akt von Gnesen, 2007, pp.9-10, ISBN 3-638-85343-8, ISBN 978-3-638-85343-9

- Andreas Lawaty, Hubert Orłowski, Deutsche und Polen: Geschichte, Kultur, Politik, 2003, p.24, ISBN 3-406-49436-6, ISBN 978-3-406-49436-9

- "Otto III | Holy Roman emperor | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- Thietmar of Merseburg, Chronicon, IV, 49: «Qui facie clarus ac fide precipuus VIIII Kal. Febr. Romani corona imperii exivit ab hoc seculo».

- Norwich, John Julius (1993), Byzantium: The Apogee, pg. 253

- Bryce 1904, p. 147.

- Reuter 1995, p. 260.

- Reuter 1995, p. 260–261.

- Reuter 1995, p. 261.

- Bryce 1904, p. 207.

- Althoff, Gerd (2003). Otto III (PDF). Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 0271022329. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Althoff, Gerd. Otto III. Penn State Press, 2002. ISBN 0-271-02232-9

- Bryce, James (1904). The Holy Roman Empire (new ed.). London: Macmillan & Co.

- Comyn, Robert. History of the Western Empire, from its Restoration by Charlemagne to the Accession of Charles V, Vol. I. 1851

- Duckett, Eleanor (1968). Death and Life in the Tenth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói ("Rulers of the Árpád dynasty"). I.P.C. KÖNYVEK Kft. ISBN 963-7930-97-3.

- Longhena, Mario; Levi Spinazzola, Alda; Pettorelli, Arturo; Parigi, Luigi; De Marinis, Tammaro; Carotti, Natale (1935). "Piacenza". Enciclopedia Italiana. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Moehs, Teta E. (1972). Gregorius V, 996–999: A Biographical Study. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann.

- Reuter, Timothy (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, c.900–c.1024. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 891. ISBN 9780521364478. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Reuter, Timothy, ed. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. III: c. 900–c. 1024, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Otto III.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 374–375.