Honeycomb

A honeycomb is a mass of hexagonal prismatic cells built from wax by honey bees in their nests to contain their brood (eggs, larvae, and pupae) and stores of honey and pollen.

.jpg.webp)

Beekeepers may remove the entire honeycomb to harvest honey. Honey bees consume about 8.4 lb (3.8 kg) of honey to secrete 1 lb (450 g) of wax,[1] and so beekeepers may return the wax to the hive after harvesting the honey to improve honey outputs. The structure of the comb may be left basically intact when honey is extracted from it by uncapping and spinning in a centrifugal machine, more specifically a honey extractor. If the honeycomb is too worn out, the wax can be reused in a number of ways, including making sheets of comb foundation with hexagonal pattern. Such foundation sheets allow the bees to build the comb with less effort, and the hexagonal pattern of worker-sized cell bases discourages the bees from building the larger drone cells. Fresh, new comb is sometimes sold and used intact as comb honey, especially if the honey is being spread on bread rather than used in cooking or as a sweetener.

Broodcomb becomes dark over time, due to empty cocoons and shed larval skins embedded in the cells, alongside being walked over constantly by other bees, resulting in what is referred to as a 'travel stain'[2] by beekeepers when seen on frames of comb honey. Honeycomb in the "supers" that are not used for brood (e.g. by the placement of a queen excluder) stays light-colored.

Numerous wasps, especially Polistinae and Vespinae, construct hexagonal prism-packed combs made of paper instead of wax; in some species (such as Brachygastra mellifica), honey is stored in the nest, thus technically forming a paper honeycomb. However, the term "honeycomb" is not often used for such structures.

Geometry

The axes of honeycomb cells are always nearly horizontal, with the open end higher than the back end. The open end of a cell is typically referred to as the top of the cell, while the opposite end is called the bottom. The cells slope slightly upwards, between 9 and 14°, towards the open ends.

Two possible explanations exist as to why honeycomb is composed of hexagons rather than any other shape. First, the hexagonal tiling creates a partition with equal-sized cells, while minimizing the total perimeter of the cells. Known in geometry as the honeycomb conjecture, this was given by Jan Brożek and mathematically proven much later by Thomas Hales. Thus, a hexagonal structure uses the least material to create a lattice of cells within a given volume. A second reason, given by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, is that the shape simply results from the process of individual bees putting cells together: somewhat analogous to the boundary shapes created in a field of soap bubbles. In support of this, he notes that queen cells, which are constructed singly, are irregular and lumpy with no apparent attempt at efficiency.[3]

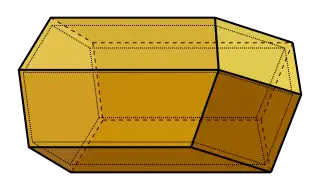

The closed ends of the honeycomb cells are also an example of geometric efficiency, though three-dimensional.[4] The ends are trihedral (i.e., composed of three planes) sections of rhombic dodecahedra, with the dihedral angles of all adjacent surfaces measuring 120°, the angle that minimizes surface area for a given volume. (The angle formed by the edges at the pyramidal apex, known as the tetrahedral angle, is approximately 109° 28' 16" (= arccos(−1/3))

The shape of the cells is such that two opposing honeycomb layers nest into each other, with each facet of the closed ends being shared by opposing cells.[4]

Individual cells do not show this geometric perfection: in a regular comb, deviations of a few percent from the "perfect" hexagonal shape occur.[4] In transition zones between the larger cells of drone comb and the smaller cells of worker comb, or when the bees encounter obstacles, the shapes are often distorted. Cells are also angled up about 13° from horizontal to prevent honey from dripping out.[5]

In 1965, László Fejes Tóth discovered that the trihedral pyramidal shape (which is composed of three rhombi) used by the honeybee is not the theoretically optimal three-dimensional geometry. A cell end composed of two hexagons and two smaller rhombi would actually be .035% (or about one part per 2850) more efficient. This difference is too minute to measure on an actual honeycomb, and irrelevant to the hive economy in terms of efficient use of wax, considering wild comb varies considerably from any mathematical notion of "ideal" geometry.[6][7]

Role of wax temperature

Bees use their antennae, mandibles and legs to manipulate the wax during comb construction, while actively warming the wax.[8] During the construction of hexagonal cells, wax temperature is between 33.6–37.6 °C (92.5–99.7 °F), well below the 40 °C (104 °F) temperature at which wax is assumed to be liquid for initiating new comb construction.[8] The body temperature of bees is a factor for regulating an ideal wax temperature for building the comb.[9]

Gallery

A Western honey bee on a honeycomb

A Western honey bee on a honeycomb The bees begin to build the comb from the top of each section. When a cell is filled with honey, the bees seal it with wax.

The bees begin to build the comb from the top of each section. When a cell is filled with honey, the bees seal it with wax. Natural honeycombs on a building

Natural honeycombs on a building Honeycomb with eggs and larvae

Honeycomb with eggs and larvae Closeup of an abandoned Apis florea nest in Thailand. The hexagonal grid of wax cells on either side of the nest are slightly offset from each other. This increases the strength of the comb and reduces the amount of wax required to produce a robust structure.

Closeup of an abandoned Apis florea nest in Thailand. The hexagonal grid of wax cells on either side of the nest are slightly offset from each other. This increases the strength of the comb and reduces the amount of wax required to produce a robust structure. Honeycomb

Honeycomb The lower part of the natural comb of Apis dorsata has a number of unoccupied cells

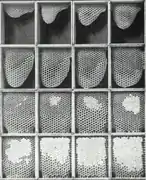

The lower part of the natural comb of Apis dorsata has a number of unoccupied cells "Artificial honeycomb" foundation plate in which bees have already completed some cells

"Artificial honeycomb" foundation plate in which bees have already completed some cells Honeycomb section containing transition from worker to drone (larger) cells – here bees make irregular and five-cornered cells (marked with red dots)

Honeycomb section containing transition from worker to drone (larger) cells – here bees make irregular and five-cornered cells (marked with red dots) Western honeybees and honeycomb

Western honeybees and honeycomb Honeycombs made by machine with beeswax and with the whole structure of the hexagonal cell already built

Honeycombs made by machine with beeswax and with the whole structure of the hexagonal cell already built Coat of arms of the town of Viļāni, Latvia

Coat of arms of the town of Viļāni, Latvia

References

- Graham, Joe. The Hive and the Honey Bee. Hamilton/IL: Dadant & Sons; 1992; ISBN.

- "Glossary of Bee Terms". Montgomery County Beekeepers Association. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

dark discoloration on the surface of comb honey left on the hive for some time, caused by bees tracking propolis over the surface.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1942). On Growth and Form. Dover Publications. ISBN.

- Nazzi, F (2016). "The hexagonal shape of the honeycomb cells depends on the construction behavior of bees". Scientific Reports. 6: 28341. Bibcode:2016NatSR...628341N. doi:10.1038/srep28341. PMC 4913256. PMID 27320492.

- Frisch, Karl von (1974). Animal Architecture. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 9780151072514.

- Bessiere, Gustavo (1987). Il Calcolo Differenziale e Integrale—Reso Facile ed Attraente.IL (in Italian) (VII ed.). Milan: Hoepli. ISBN 9788820310110.

- Gianni A. Sarcone. "The solved angular puzzle of the honeycombs' cells". 2004.

- Bauer, D; Bienefeld, K (2013). "Hexagonal comb cells of honeybees are not produced via a liquid equilibrium process". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (1): 45–9. Bibcode:2013NW....100...45B. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0992-3. PMID 23149932. S2CID 11552726.

- Pirk, C. W.; Hepburn, H. R.; Radloff, S. E.; Tautz, J (2004). "Honeybee combs: Construction through a liquid equilibrium process?". Naturwissenschaften. 91 (7): 350–3. Bibcode:2004NW.....91..350P. doi:10.1007/s00114-004-0539-3. PMID 15257392. S2CID 31547154.