Honey hunting

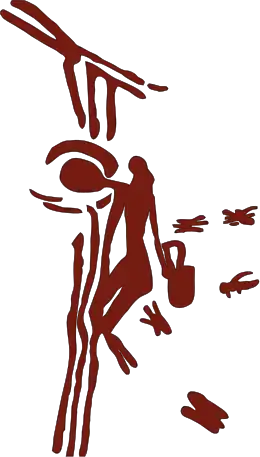

Honey hunting or honey harvesting is the gathering of honey from wild bee colonies. It is one of the most ancient human activities and is still practiced by aboriginal societies in parts of Africa, Asia, Australia and South America. Some of the earliest evidence of gathering honey from wild colonies is from rock painting, dating to around 8,000 BC. In the Middle Ages in Europe, the gathering of honey from wild or semi-wild bee colonies was carried out on a commercial scale.

Gathering honey from wild bee colonies is usually done by subduing the bees with smoke and breaking open the tree or rocks where the colony is located, often resulting in the physical destruction of the colony.

Africa

Honey hunting in Africa is a part of the indigenous cultures in many parts and hunters have hunted for thousands of years.

Asia

Nepal

Honey hunting in Nepal is also commonly known as wild honey hunting, it holds deep cultural significance in Nepal, particularly among the indigenous Gurung and Magar communities. The tradition has been passed down through generations, and honey hunters are regarded with great respect and admiration. Wild Honey is not only valued for its psychoactive effects but is also used in traditional medicine for its purported healing properties.

A documentary by freelance photojournalists Diane Summers and Eric Valli on the Honey hunters of Nepal [1] documents Gurung tribesmen of west-central Nepal entering the jungle in search of wild honey where they use indigenous tools under precarious conditions to collect honey.

Twice a year high in the Himalayan foothills of central Nepal teams of men gather around cliffs that are home to the world's largest honeybee, Apis laboriosa. As they have for generations, the men come to harvest the Himalayan cliff bee's honey.

This was also documented in a BBC2 documentary in August 2008 entitled Jimmy and the Wild Honey Hunters-Sun. An English farmer travelled into the Himalayan foothills on a honey hunting expedition. The world's largest honeybee, A. laboriosa is over twice the size of those in the UK where their larger bodies have adapted to the colder climate for insulation. The documentary involved ascending a 200-foot rope ladder and balancing a basket and a long pole to chisel away at a giant honeycomb of up to 2 million bees and catch it in the basket.

For centuries the Gurung people of the country of Nepal risked their lives to collect wild cliff honey. Photos of Andrew Newey capture this dying tradition.[2]

Bangladesh and India

In the Sunderban forest, shared by Bangladesh and India's West Bengal, estuarine forests are the area of operation of honey hunters.[3] They are known as "Mawals". This is a dangerous occupation as many honeyhunters die in tiger attacks which are common in this area. The harvest ritual, which varies slightly from community to community, begins with a prayer and sacrifice of flowers, fruits, and rice. Then a fire is lit at the base of the cliff to smoke the bees from their honeycombs.

Indonesia

The traditional method of harvesting honey in Riau Province is called Menumbai. This skill is performed by Petalangan people who live in the Sialang tree in the Tanah Ulayat forest area, Pelalawan. Menumbai Pelalawan is a way of taking honey from a beehive using a bucket and rope. To prevent the bees from stinging the body, the taking of the honey is accompanied by the recitation of mantras and rhymes. Menumbai Pelalawan is only done in wild bee hives and only in the afternoon.

Europe

Function

As early as the Stone Age, people collected the honey of wild bees, but this was not done commercially. From the Early Middle Ages it became a trade, known in German-speaking central Europe, for example, as a Zeidler or Zeitler, whose job it was to collect the honey of wild, semi-wild or domestic bees in the forests. Unlike modern beekeepers, they did not keep the bees in man-made wooden beehives. Instead, they cut holes as hives in old trees at a height of about six meters and fitted a board over the entrance. Whether a colony of bees nested there or not depended entirely on the natural environment and that could change every year. The tree tops were also cut off in order to prevent wind damage.

Distribution

Extremely valuable, if not a prerequisite for tree beekeeping, were conifer stands. Important locations for honey hunting in the Middle Ages were in the regions of the Fichtel Mountains and the Nuremberg Imperial Forest. In Bavaria forest beekeeping is recorded as early as the year 959 in the vicinity of Grabenstätt. But even in the area of today's Berlin, there was extensive honey gathering, especially in the then much larger Grunewald.

In the area around Nuremberg there are still numerous references to an earlier flourishing honey hunting tradition such as the castle of Zeidlerschloss in Feucht. Honey was important for Nuremberg's gingerbread production; the Nuremberg Reichswald ("The bee garden of the Holy Roman Empire") provided plenty of it.

References

- Expedition, Go For Nepal Treks &. "A Day with Honey Hunters in Nepal". Go For Nepal Treks & Expedition. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- "The ancient art of honey hunting in Nepal - in pictures". The Guardian. 27 February 2014.

- "A honey-collecting odyssey". 8 June 2003.

https://hikingbees.com/blog/best-honey-hunting-destinations-in-nepal/

Literature and Film

- Honeyland, 2019 documentary set in North Macedonia

- Eva Crane: The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. Duckworth, London, 2000. ISBN 0-7156-2827-5.

- Hermann Geffcken, Monika Herb, Marian Jeliński und Irmgard Jung-Hoffman (Hrsg.): Bienenbäume, Figurenstöcke und Bannkörbe. Fördererkreis d. naturwiss. Museen Berlins, Berlin 1993. ISBN 3-926579-03-X.

- Karl Hasel, Ekkehard Schwartz: Forstgeschichte. Ein Grundriss für Studium und Praxis. 2nd, updated edition. Kessel, Remagen, 2002, ISBN 3-935638-26-4.

- Richard B. Hilf: Der Wald. Wald und Weidwerk in Geschichte und Gegenwart – Erster Teil [reprint]. Aula, Wiebelsheim, 2003, ISBN 3-494-01331-4.

- Klaus Baake: Das Zeidelprivileg von 1350. Munich, 1990.

- Mark Synnott: “The Last Honey Hunter” p. 80. National Geographic. Vol. 232. No. 1. July 2017.