Riau

Riau is a province of Indonesia. It is located on the central eastern coast of Sumatra along the Strait of Malacca. The province shares land borders with North Sumatra to the northwest, West Sumatra to the west, and Jambi to the south, and a maritime border with the Riau Islands and the country of Malaysia to the east. It is the second-largest province in the island of Sumatra after South Sumatra, and is slightly larger than Jordan. According to the 2020 census, Riau had a population of 6,394,087 across a land area of 89,935.90 square kilometres;[6] the official estimate as at mid 2022 was 6,614,384.[1] The province comprises ten regencies and two cities, with Pekanbaru serving as the capital and largest city.

Riau | |

|---|---|

| Province of Riau | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): | |

Location of Riau in Indonesia | |

OpenStreetMap | |

| Coordinates: 0.54°N 101.45°E | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Region | Sumatra |

| Province status | 10 August 1957 |

| Capital and largest city | Pekanbaru |

| Government | |

| • Body | Riau Provincial Government |

| • Governor | Syamsuar |

| • Vice Governor | Edy Nasution |

| Area | |

| • Total | 89,935.90 km2 (34,724.45 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 5th |

| Highest elevation (Mount Mandiangin) | 1,284 m (4,213 ft) |

| Population (mid 2022 estimate)[1] | |

| • Total | 6,614,384 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 74/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 24th |

| Demographics[2] | |

| • Ethnic groups | 45% Riau Malay 25% Javanese 12% Batak 8% Minangkabau 4% Banjarese 1.95% Buginese 1.85% Chinese 1.42% Sundanese 1.30% Nias 2.11 Others |

| • Religion | 87.05% Islam 10.83% Christianity - 9.76% Protestant - 1.07% Catholic 2.05% Buddhism 0.03% Confucianism 0.016% Folk religion 0.011% Hinduism[3] |

| • Languages | Indonesian (official), Riau Malay (dominant), Minangkabau, Hokkien |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | ID-RI |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022[4] |

| - Total | Rp 991.6 trillion (5th) US$ 66.8 billion US$ 208.4 billion (PPP) |

| - Per capita | Rp 149.9 million (4th) US$ 10,096 US$ 31,504 (PPP) |

| - Growth | |

| HDI | |

| Website | riau.go.id |

Historically, Riau has been a part of various monarchies before the arrival of European colonial powers. Muara Takus temple in Kampar Regency, believed to be a remnant of the Buddhist empire of Srivijaya c. 11th-12th century. Following the spread of Islam in the 14th century, the region was then under control of Malay sultanates of Siak Sri Indrapura, Indragiri, and Johor. The sultanates later became protectorate of the Dutch and were reduced to puppet states of the Dutch East Indies. After the establishment of Indonesia in 1945, Riau belonged to the republic's provinces of Sumatra (1945–1948) and Central Sumatra (1948–1957). On 10 August 1957, the province of Riau was inaugurated and it included the Riau Islands until 2004.

Although Riau is predominantly considered the land of Malays, it is a highly diverse province. In addition to Malays constituting one-third of the population, other major ethnic groups include Javanese, Minangkabau, Batak, and Chinese. The local Riau dialect of Malay language is considered as the lingua franca in the province, but Indonesian, the standardized form of Malay is used as the official language and also as the second language of many people. Other than that, different languages such as Minangkabau, Hokkien and varieties of Batak languages are also spoken.

Riau is one of the wealthiest provinces in Indonesia and is rich in natural resources, particularly petroleum, natural gas, rubber, palm oil and fibre plantations. Extensive logging and plantation development in has led to a massive decline in forest cover Riau, and associated fires have contributed to haze across the larger region.

Etymology

There are three possible origins of the word riau which became the name of this province. First, from the Portuguese word, "rio" which means river.[7][8] In 1514, there was a Portuguese military expedition that traced the Siak River, in order to find the location of a kingdom they believed existed in the area, and at the same time to pursue followers of Sultan Mahmud Shah who fled after the fall of the Malacca Sultanate.[9]

The second version claims that riau comes from the word riahi which means sea water. The word is allegedly derived from the figure of Sinbad al-Bahar in the book of the One Thousand and One Nights.[8]

Another version is that riau is derived from the Malay word riuh, which means crowded, frenzied working people. This word is believed used to reflect the nature of the Malay people in present-day Bintan. The name is likely to have become famous since Raja Kecil moved the Malay kingdom center from Johor to Ulu Riau in 1719.[8] This name was used as one of the four main sultanates that formed the kingdoms of Riau, Lingga, Johor and Pahang. However, as the consequences of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 between the Netherlands and United Kingdom, the Johor-Pahang sultanates fell under British influence, while the Riau-Lingga sultanates fell under Dutch influence.[10][11]

History

Prehistoric era

Riau is thought to have been inhabited since between 40,000 and 10,000 BC, with the discovery of tools from the Pleistocene era in the Sengingi River area in Kuantan Singingi Regency in August 2009. Stone tools found include: an axle, a drawstring, and shale and core stone axes. The research team also found some wood fossils estimated to be older than the stone tools. It is suspected the tool users were Pithecanthropus erectus (reclassified as Homo erectus) similar to those found in Sangiran, Central Java. These tools proved the existence of prehistoric settlement in Riau. Earlier settlement was assumed to be possible in the area since the discovery of the Muara Takus Temple in Kampar in 1860.[12][13]

Early historic era

The Malay kingdoms in Riau were at first based on the Buddhist Srivijaya Empire. This is evidenced by the Muara Takus Temple which was thought to be the center of the Srivijaya government in Riau. Its architecturally resembles temples that can be found in India. In addition, French historian George Cœdès also discovered the similarity of the Srivijaya governmental structure and the Malay sultanates of the 15th century.[14] The earliest text that deals with the Malay world is Sulalatus Salatin (Malay Annals) by Tun Sri Lanang, in 1612.[15] According to the annals, Bukit Seguntang in modern-day Palembang in South Sumatra is where Sang Sapurba came to the world and his descendants would scatter throughout the Malay world. His descendants such as Sang Mutiara would become king in Tanjungpura and Sang Nila Utama would become king in Bintan before finally moving to Singapura.[16] Before the arrival of Islam to the archipelago, many parts of the Riau region were under the Srivijaya Empire between the 7th to the 14th century which was greatly influenced by the Hindu-Buddhist tradition.[17] Islam was introduced to the region when the Maharaja of Srivijaya sent a letter to Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz of the Umayyad Caliphate in Egypt containing a request to send a messenger to introduce Islamic law to him.[18]

Islamic sultanates

In the 12th century, the entry of Islam into the archipelago was carried through the Samudera Pasai Sultanate in Aceh which was the first Islamic sultanate in the archipelago.[19] The process of the spread of Islam occurred through trade, marriage and missionary activities of Muslim clerics. These factors led to the spread and growth of Islamic influence throughout the Malay world. The strong acceptance of Islam by Malay people is the aspect of equality, which contrasted the caste system in Hinduism, where lower class caste people were less than members of a higher castes.[20]

The golden age of Islam in the region was when Malacca became an Islamic sultanate. Many elements of Islamic law, including political and administrative sciences were incorporated into Malacca law, especially the Udang-Undang Melaka (Law of Melaka). The ruler of Malacca received the title 'Sultan' and was responsible for Islam in his kingdom. In the 15th century, Islam spread and developed throughout the Melaka region including the entire Malay Peninsula, Riau Islands, Bintan, Lingga, Jambi, Bengkalis, Siak, Rokan, Indragiri, Kampar, and Kuantan. Malacca is considered a catalyst in the expansion of Islam into other areas such as Palembang, Sumatra, Patani in southern Thailand, North Kalimantan, Brunei and Mindanao.[15]

According to the journals of the Portuguese explorer Tomé Pires between 1513 and 1515, Siak an area that lies between Arcat and Indragiri a port city under a Minangkabau king,[21] became a Malacca vassal before being conquered by the Portuguese. Since the fall of Malacca to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the Johor Sultanate has claimed Siak as part of its sovereign territory. This continued until the arrival of Sultan Abdul Jalil Rahmat Shah or Raja Kecil who later founded the Siak Sultanate.[22] In the Syair Perang Siak, it is told that Raja Kecil was asked to become the ruler of Siak for the consensus of the people in Bengkalis. This aims to release Siak from the influence of the Johor Sultanate.[23] While according to the Hikayat Siak, Raja Kecil was also called the true inheritor of the throne of the Sultan of Johor who lost the power struggle.[24] Based on the correspondence of the Sultan Indermasyah with the Dutch Governor-General in Malacca at that time, it was mentioned that Sultan Abdul Jalil was his brother who was sent for business affairs with the VOC.[25] Sultan Abdul Jalil then wrote a letter addressed to the Dutch, calling himself the Raja Kecil of Pagaruyung, that he would take revenge for the death of the Sultan of Johor.[26]

In 1718, Raja Kecil succeeded in conquering the Johor Sultanate, at the same time crowning himself as the Sultan of Johor with the title Yang Dipertuan Besar Johor.[22] But in 1722, a rebellion led by Raja Sulaiman, the son of the former Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah IV, demanded the right to the throne of Johor. With the help of Bugis mercenaries, Raja Sulaiman then succeeded in seizing the throne of Johor, and established himself as the ruler of Johor in Peninsular Malaysia, crowning himself as Sultan Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah of Johor, while Raja Kecil moved to Bintan and in 1723 established a new government center on the bank of the Siak River with the name Siak Sri Inderapura.[23] While the center of the Johor government which had been around the estuary of the Johor River was abandoned. Whereas the claim of Raja Kecil as the legitimate heir to the throne of Johor, was recognized by the Orang Laut community. The Orang Laut is a Malay sub-group that resides in the Riau Islands region that stretches from east Sumatra to the South China Sea, and this loyalty continued until the collapse of the Siak Sultanate.[27]

By the late 18th century, the Siak Sultanate had become the dominant power on the eastern coast of Sumatra. In 1780, the Siak Sultanate conquered the Sultanate of Langkat, and made the area its protectorate, alongside the Deli and Serdang Sultanates.[28][29] Under the ties of a cooperation agreement with the VOC, in 1784 the Siak Sultanate helped the VOC attack and subdue the Selangor Sultanate.[30] Previously they had collaborated to quell the Raja Haji Fisabilillah rebellion on Penyengat Island.

The Siak Sultanate took advantage of the trade supervision through the Straits of Malacca, as well as the ability to control pirates in the region. The progress of Siak's economy can be seen from the Dutch records which stated that in 1783 there were around 171 merchant ships making a voyage from Siak to Malacca.[31][32] Siak is a trading triangle between the Netherlands in Malacca and the United Kingdom on Penang.[33] But on the other hand, the glory of Siak caused jealousy of the descendants of Yang Dipertuan Muda, especially after the loss of their power in the Riau Islands. The attitude of dislike and hostility towards the Sultan of Siak was, seen in the Tuhfat al-Nafis, where in the description of the story they describe the Sultan of Siak as "a person who is greedy for the wealth of the world".[34]

The dominance of the Siak Sultanate towards the eastern coast of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula was quite significant. They were able to replace the influence of Johor before on the control of the trade route in the Strait of Malacca. In addition, the Siak Sultanate also emerged as a key holder of the Minangkabau highland, through three main rivers, of Siak, Kampar, and Kuantan, which had previously been the key to the glory of Malacca. However, the progress of Siak's economy faded caused by the turmoil in the Minangkabau interior known as the Padri War.[35]

Colonial rule

The expansion of Dutch colonialization into the eastern part of Sumatra caused the influence of the Siak Sultanate to wane, leading to the independence of the Deli Sultanate, the Asahan Sultanate, the Langkat Sultanate, and the Inderagiri Sultanate.[36] Likewise in Johor, where a sultan of the descendants of Tumenggung Johor was crowned, under British protection in Singapore.[37][38] While the Dutch restored the position of the Yang Dipertuan Muda on Penyengat Island, and later established the Riau-Lingga Sultanate on Lingga Island. In addition, the Netherlands also reduced the territory of Siak, by establishing the Residency of Riouw (Dutch: Residentie Riouw) which was part of the Dutch East Indies government based in Tanjung Pinang.[39][40][41]

British control of the Straits of Malacca, prompted the Sultan of Siak in 1840 to accept the offer of a new treaty to replace the agreement they had made earlier in 1819. This agreement made the Siak Sultanate area smaller and sandwiched it between other small kingdoms which were protected by Britain.[42] Likewise, the Dutch made the sultanate a protectorate of the Dutch East Indies,[43] after forcing the Sultan of Siak to sign an agreement on 1 February 1858.[35][44] From the agreement, the sultanate lost its sovereignty, then in the appointment of a new sultan, the sultanate must get approval from the Netherlands. Furthermore, under regional supervision, the Dutch established a military post in Bengkalis and banned the Sultan of Siak from making agreements with foreign parties without the approval of the Dutch East Indies government.[35]

Changes in the political map over the control of the Malacca Strait, the internal disputes of Siak and competition with Britain and the Netherlands, weakened the influence of the Siak Sultanate over the territories it had once conquered.[45] A tug of war between the interests of foreign forces caused the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaties of 1870–71 between the British and the Dutch, put Siak in a weak bargaining position.[46] Then based on the agreement on 26 July 1873, the Dutch East Indies government forced the Sultan of Siak to hand over the Bengkalis area to the Riouw Residency.[47] But in the midst of this pressure, the Siak Sultanate still remained until Indonesia's independence, even though during the Japanese occupation most of the military power of the Siak Sultanate was no longer significant.[48]

At about the same time, the Indragiri Sultanate also began to be influenced by the Dutch, but only came under the control of Batavia in 1938. Dutch control of Siak later became the beginning of the outbreak of the Aceh War.

On the coast, the Dutch moved quickly to abolish the sultanates that did not submit to the government in Batavia. The Dutch appointed a resident in Tanjung Pinang to supervise coastal areas, and the Dutch succeeded in toppling the Sultan of Riau-Lingga, Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Syah in February 1911.[49]

Japanese occupation

During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, Riau was one of the primary strategic targets. The Japanese army occupied Rengat on 31 March 1942.[50] All of Riau was quickly occupied by the Japanese. A relic of the Japanese occupation is the 220 km railway line that connects Muaro Sijunjung in West Sumatra and Pekanbaru, also known as the Pekanbaru Death Railway which is now abandoned. Hundreds of thousands of Riau people were forced to work by the Japanese to complete the project.[51][52][53] Japan led the construction of the railroad using forced labor and prisoners of war. The construction took 15 months through mountains, swamps and fast-flowing rivers.[54] As many as 6,500 Dutch (mostly Indo-Europeans) and British prisoners of wars and more than 100,000 romusha Indonesians (mostly Javanese) were mobilized by the Japanese military. When the project was completed in August 1945, almost one third of European prisoners of war and more than half of Indonesian workers died. The railroad was intended as a medium for transporting coal and soldiers from Pekanbaru to Muaro Sijunjung on the west of Sumatra. Construction of the railroad was completed on 15 August 1945, before the Japanese surrendered. The railroad was used only once to transport prisoners of war out of the area. The line was then abandoned.[55]

Independence and contemporary era

At the beginning of Indonesia's independence, the former Riau Residency was merged and incorporated into the Sumatra Province based in Bukittinggi. Along with the crackdown on PRRI sympathizers, Sumatra was divided into three provinces, North Sumatra, Central Sumatra, and South Sumatra. Central Sumatra became a stronghold of the PRRI, this caused the central government to breakup Central Sumatra in order to weaken the PRRI movement,[56] in 1957, based on Emergency Law Number 19 of 1957,[57] Central Sumatra was divided into three provinces, Riau, Jambi and West Sumatra. The newly formed Riau province was composed of the former territory of the Siak Sri Sultanate of Inderapura and the Riau Residency as well as the Kampar.

As Riau was one of the areas influenced by the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia, the central government conducted Operation Tegas to quell the rebellion, under the leadership of Kaharuddin Nasution, who later became governor of the province, succeeded in quelling the remnants of PRRI sympathizers.[58]

Afterwards, the central government began to consider moving the provincial capital from Tanjung Pinang to Pekanbaru, which is more centrally located. The government established Pekanbaru as the new provincial capital on 20 January 1959 through Kepmendagri No. December 52 / I / 44–25.[59]

After the fall of the Old Order, Riau became one of the pillars of the New Order's economic development.[60] In 1944, geologist Richard H. Hopper, Toru Oki and their team discovered the largest oil well in Southeast Asia, in Minas, Siak. This well was originally named Minas No. 1. Minas is famous for its Sumatra Light Crude (SLC) oil which is good quality as it has low sulfur content.[61] In the early 1950s, new oil wells were found in Minas, Duri, Bengkalis, Pantaicermin, and Petapahan. Petroleum extraction in Riau began in the Siak Block in September 1963, with the signing of a work contract with PT California Texas Indonesia (now Chevron Pacific Indonesia).[62] This province contributed 70% of Indonesia's oil production in the 1970s.[63]

Riau was also the main destination for the transmigration program launched by the Suharto administration. Many families from Java moved to the newly opened oil palm plantations in Riau, forming a separate community.[64]

In 1999, Saleh Djasit was elected as the second native Riaunese (besides Arifin Achmad) and first elected by the Provincial House of Representatives as governor. His administration saw the separation of the Riau Archipelago to become Riau Islands Province in 2002, leaving Riau with just the mainland territories. In 2003, former Regent of Indragiri Hilir, Rusli Zainal, was elected governor, and was re-elected through direct elections by the people in 2008. Starting on 19 February 2014, Riau Province was officially led by the governor, Annas Maamun, leading for 7 months, Annas Maamun was removed after he was arrested by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in a case of land use change in Kuantan Singingi Regency.

Geography

Geographically, Riau is located at position 02 ° 25 'LU-01 ° 15 ° LS and 100 ° 03'-104 ° 00' BT. The area is quite extensive and is located in the central part of Sumatra. Riau is directly adjacent to North Sumatra and the Straits of Malacca in the north, Jambi to the south, West Sumatra to the west and the Riau Islands in the east. The province shares maritime borders with Singapore and Malaysia.

In general, the geography of Riau consists of mountains, lowlands, and islands. The mountain area lies in the western part, namely the Bukit Barisan Mountains, near the border of West Sumatra. The elevation decreases towards the east, making most of the central and eastern part of the province covered with lowlands. Off the eastern coast lies the Strait of Malacca where several island lies.

Climate

In general, Riau Province has a wet tropical climate that is influenced by two seasons, namely the rainy and dry seasons. The average rainfall received by Riau Province is between 2,000 – 3,000 mm / year with an average annual rainfall of 160 days. The areas that received the most rain were Rokan Hulu Regency and Pekanbaru City. Meanwhile, the area that received the least rainfall was Siak Regency.

The average air temperature of Riau is 25.9 °C with maximum temperatures reaching 34.4 °C and minimum temperatures reach 20.1 °C. The highest temperature occurs in urban areas on the coast. On the contrary, the lowest temperature covers the high mountains and mountains. Air humidity can reach an average of 75%. Slightly different for the island region in the eastern region is also influenced by the characteristics of the sea climate.

| Climate data for Pekanbaru | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36 (97) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

40 (104) |

37 (99) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

40 (104) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

18 (64) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

13 (55) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

13 (55) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 240 (9.4) |

199 (7.8) |

262 (10.3) |

257 (10.1) |

203 (8.0) |

133 (5.2) |

123 (4.8) |

177 (7.0) |

224 (8.8) |

280 (11.0) |

312 (12.3) |

286 (11.3) |

2,696 (106) |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org (average temps and precip)[65] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase (extremes)[66] | |||||||||||||

As in most other province of Indonesia, Riau has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) bordering on a tropical monsoon climate. The climate is very much dictated by the surrounding sea and the prevailing wind system. It has high average temperature and high average rainfall.

Ecology

Forest cover in Riau has declined from 78% in 1982 to only 33% in 2005.[67] This has been further reduced an average of 160,000 hectares on average per year, leaving 22%, or 2.45 million hectares left as of 2009.[68] Fires associated with deforestation have contributed to serious haze over the province and cities to the East, such as Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia[69][70][71]

Giam Siak Kecil – Bukit Batu Biosphere Reserve, Indonesia, is a peatland area in Sumatra featuring sustainable timber production and two wildlife reserves, which are home to the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran elephant, Malayan tapir, and Malayan sun bear. Research activities in the biosphere include the monitoring of flagship species and in-depth study on peatland ecology. Initial studies indicate a real potential for sustainable economic development using native flora and fauna for the economic benefit of local inhabitants.

Cagar Biosfer Giam Siak Kecil Bukit Batu (CB-GSK-BB) is one of seven Biosphere Reserves in Indonesia. They are located in two areas of Riau Province, Bengkalis and Siak. CB-GSK-BB is a trial presented by Riau at the 21st Session of the International Coordinating Council of Man and the Biosphere (UNESCO) in Jeju, South Korea, on 26 May 2009. CB-GSK-BB is one of 22 proposed locations in 17 countries accepted as reserves for the year. A Biosphere Reserve is the only internationally recognised concept of environmental conservation and cultivation. Thus the supervision and development of CB-GSK-BB is a worldwide concern at a regional level.

CB-GSK-BB is a unique type of Peat Swamp Forest in the Kampar Peninsula Peat Forest (with a small area of swamp). Another peculiarity is that the CB-GSK-BB was initiated by private parties in co-operation with the government through BBKSDA (The Center for the Conservation of Natural Resources), including the notorious conglomerate involved in forest destruction, Sinar Mas Group, owning the largest paper and pulp company in Indonesia.

Government

The Province of Riau is led by a governor who is elected directly with his representative for a 5-year term. In addition to being a regional government, the Governor also acts as a representative or extension of the central government in the province, whose authority is regulated in Law No. 32 of 2004 and Government Regulation number 19 of 2010.

While the relationship between the provincial government and the regency and city governments is not a sub-ordinate, each of these regional governments governs and manages government affairs according to the principle of autonomy and co-administration.

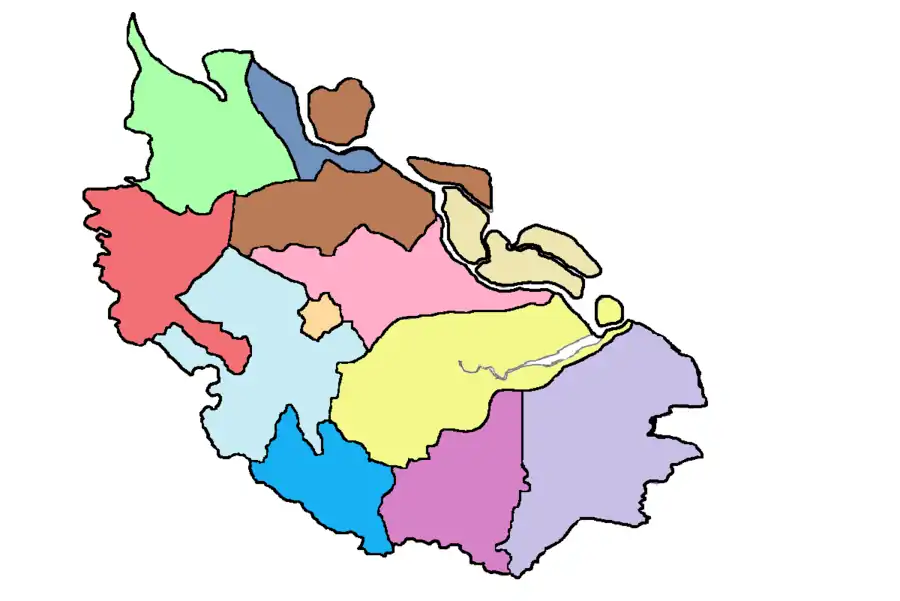

Administrative divisions

When the province of Riau was created on 10 August 1957 from the splitting of the former province of Central Sumatra, it consisted of five regencies - Bengkalis, Bintan (covering the offshore archipelagoes now comprising the Riau Islands Province), Indragiri Hilir, Indragiri Hulu and Kampar - together with the independent city of Pekanbaru. On 4 October 1999 four of these regencies were divided up in a wholesale reorganisation: Bengkalis Regency was split up into Rokan Hilir Regency, Siak Regency and a new city of Dumai, as well as a smaller Bengkalis Regency; a new Kuantan Singingi Regency was cut out of the Indragiri Hulu Regency, while Rokan Hulu Regency and Pelalawan Regency were cut out of Kampar Regency. Finally, on the same date, the Bintan Regency was split, with a new city of Batam and new regencies of Karimun and Natuna being split off; a further city of Tanjung Pinang was cut out of the residual part of Bintan Regency on 21 June 2001; however on 24 September 2002 the five Riau Islands administrations were split off from Riau Province to form a separate Riau Islands Province. Subsequently on 19 December 2008 a new Meranti Islands Regency was cut off the remaining Bengkalis Regency.

Riau Province is subdivided into ten regencies (kabupaten) and two autonomous cities (kota), listed below with their areas and their populations at the 2010[72] and 2020[6] Censuses, and according to the official estimates as at mid 2022.[1]

| Kode Wilayah | Name of City or Regency | Area in km2 | Pop'n census 2010 | Pop'n census 2020 | Pop'n estimate mid 2022 | Capital | HDI[73] 2014 estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.01 | Kampar Regency | 10,352.80 | 688,204 | 841,332 | 878,210 | Bangkinang | 0.707 (High) |

| 14.02 | Indragiri Hulu Regency | 7,871.85 | 363,442 | 444,548 | 464,076 | Rengat | 0.671 (Medium) |

| 14.03 | Bengkalis Regency | 8,616.36 | 498,336 | 565,570 | 582,973 | Bengkalis | 0.708 (High) |

| 14.04 | Indragiri Hilir Regency | 13,521.26 | 661,779 | 654,909 | 660,747 | Tembilahan | 0.638 (Medium) |

| 14.05 | Pelalawan Regency | 13,262.11 | 301,829 | 390,050 | 410,988 | Pangkalan Kerinci | 0.686 (Medium) |

| 14.06 | Rokan Hulu Regency | 7,658.15 | 474,843 | 561,380 | 582,679 | Pasir Pangaraian | 0.670 (Medium) |

| 14.07 | Rokan Hilir Regency | 9,068.46 | 553,216 | 637,160 | 658,407 | Bagansiapiapi | 0.662 (Medium) |

| 14.08 | Siak Regency | 7,805.54 | 376,742 | 457,940 | 477,550 | Siak Sri Indrapura | 0.714 (High) |

| 14.09 | Kuantan Singingi Regency | 5,457.86 | 292,116 | 334,940 | 345,850 | Teluk Kuantan | 0.674 (Medium) |

| 14.10 | Meranti Islands Regency | 3,623.56 | 176,290 | 206,120 | 213,532 | Selat Panjang | 0.629 (Medium) |

| 14.71 | Pekanbaru City | 638.33 | 897,767 | 983,360 | 1,007,540 | Pekanbaru | 0.784 (High) |

| 14.72 | Dumai City | 2,059.61 | 253,803 | 316,782 | 331,832 | Dumai | 0.718 (High) |

Demographics

The total population of Riau spread over ten regencies and two cities as at mid 2022 reached 6,614,384 people consisting of 3,383,451 male inhabitants and 3,230,933 female inhabitants.[1] Based from the population per regency/city, the largest population was in Pekanbaru City with 506,231 male population and 501,309 female, while the smallest population was in the Kepulauan Meranti Regency where about 110,100 people were male and 103,400 were female. When viewed from the two regencies/cities which have the largest and smallest population in Riau Province, the comparison of many male population is more dominant than the female population.[74]

Ethnic groups

Riau is considered a very ethnically diverse province. As of 2010, the ethnic groups in Riau consist of Malays (43%), Javanese (25%), Minangkabau (8%), Batak (12%), Banjar (4%), Chinese (2%), and Bugis (2%).[2] The Malays are the largest ethnic group with a composition of 45% of the entire population of Riau. They generally come from coastal areas in Rokan Hilir, Dumai, Bengkalis, Pulau Meranti, up to Pelalawan, Siak, Inderagiri Hulu and Inderagiri Hilir. Riau was once the seat of great Malay sultanates, such as the Sultanate of Siak Sri Indrapura, the Pelalawan Sultanate and the Indragiri Sultanate.

There is also a sizable population Minangkabau people living in Riau, mostly in the areas bordering West Sumatra, such as Rokan Hulu, Kampar, Kuantan Singingi, and part of Inderagiri Hulu. Pekanbaru, the capital of Riau, has a Minangkabau majority, since it was once one of the Minangkabau rantau (migration) area. Many Minang in Pekanbaru have lived there for generations and has since assimilated into the Malay community.[75] Most Minang in Riau generally work as merchants and live in urban areas such as Pekanbaru, Bangkinang, Duri, and Dumai.

There are many other ethnic groups migrating from other province of Indonesia, such as the Batak Mandailing people who mostly lives in areas bordering North Sumatra such as Rokan Hulu.[76] Most of the Mandailing people now identify themselves as Malay rather than as Minangkabau or Batak. In the 19th century, the Banjarese of South Kalimantan and the Bugis of South Sulawesi also began arriving in Riau to seek better lives. Most of them settled in the Indragiri Hilir areas, especially around Tembilahan.[77][78] The opening of Caltex oil mining company in the 1940s in Rumbai, encouraged people from throughout the country to migrate to Riau.

There are sizeable Javanese and Sundanese population in Riau. Javanese forms the second-largest ethnic group in the province, forming 25.05% of the total population. Most of them migrated to Riau due to the transmigration program dating from the Dutch East Indies and continued during the Soeharto administration. The majority of them lives in transmigration communities spread throughout the region.

Likewise, the Chinese people are generally similar to the Minangkabau as many of them also work as merchants. Many Riau Chinese lives in the capital Pekanbaru, and many can also found in coastal areas in the east such as Bagansiapiapi, Selatpanjang, Rupat and Bengkalis. Most of the Chinese people in Riau are Hoklo people, whose ancestors migrated from Quanzhou in modern-day Fujian from the early 19th-century to the mid 20th-century. Some of the Riau Chinese has migrated to other parts of Indonesia, such as Medan and Jakarta, to seek better life opportunities, while some have also migrated to other countries such as Singapore and Taiwan.[79]

There are also some groups of indigenous people who live in rural areas and riverbanks, such as the Sakai people (Indonesia), Akit, Talang Mamak and Orang Laut. Some of them still leading the nomadic and Hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the remote interior of Riau, while most settled into major cities and towns in with the rise of industrialisation.[80]

Language

The people of Riau generally uses the local dialect of Malay and Indonesian, the official language of Indonesia. Malay is commonly used in coastal areas such as Rokan Hilir, Bengkalis, Dumai, Pelalawan, Siak, Indragiri Hulu, Indragiri Hilir and around the islands off the coast of Riau.[81]

The dialect of Malay spoken in Riau is considered by linguists to have one of the least complex grammars among the languages of the world, apart from creoles, possessing neither noun declensions, temporal distinctions, subject/object distinctions, nor singular/plural distinction. For example, the phrase Ayam makan (lit. 'chicken eat') can mean, in context, anything from 'the chicken is eating', to 'I ate some chicken', 'the chicken that is eating' and 'when we were eating chicken'. A possible reason for this is that Riau Malay has been used as a lingua franca for communication between different people in this area during its history, and extensive foreign-language speaker use of this kind tends to simplify the grammar of a language used.[82] The traditional script in Riau is Jawi (locally known in Indonesia as "Arab-Melayu"), an Arabic-based writing in the Malay language.[83] It is sometimes supposed that Riau Malay is the basis for the modern national language, Indonesian. However, it is instead based on Classical Malay, the court language of Johor-Riau Sultanate, based primarily from the one used in the Riau archipelago and the state of Johor, Malaysia, which is distinct from the local mainland Riau dialect.[84] Non-mainstream varieties in Riau include Sakai people (Indonesia), Orang Asli, Orang Akit, and Orang Laut.[85]

Riau Malay can be divided into two sub-dialects, namely the inland dialect and the coastal dialect.[86] The inland dialect has phonological features that are similar to Minangkabau, while coastal dialect has phonological features that are close to Malay in the regions of Selangor, Johor and Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia (because other Malaysian regions have very different dialects).[86] In addition to various other characteristics, the two subdialects are marked with words which in Indonesian are words that end with vowels /a/; the inland dialect is pronounced with vowel /o/, while in coastal dialect is pronounced with the weak vowel /e/ . Some examples include: /bila/, /tiga/ and /kata/ in Indonesian (if, three and word in English respectively) will be pronounced in inland dialect as /bilo/, /tigo/ and /kato/ respectively. While in the coastal dialect it will be pronounced as /bile/, /tige/ and /kate/ respectively.[86]

The Minangkabau language is widely used the Minangkabau people in Riau, especially in the areas bordering West Sumatra such as Kampar, Kuantan Singingi and Rokan Hulu, which are culturally allied to Minang as well as migrants from West Sumatra.[87] It is also currently being the lingua franca of Pekanbaru, the capital city in addition to Indonesian. The pronunciation of Riau Minangkabau is similar to the Payakumbuh-Batusangkar dialect, even differs from that of other dialects varieties of West Sumatra. Historically, Minangkabau language used in the Pagaruyung highlands is now spoken in the lower Siak River basin following the waves of migration from West Sumatra.

In addition, Hokkien is also still widely used among the Chinese community, especially those living in Pekanbaru, Selatpanjang, Bengkalis, and Bagansiapiapi. The Hokkien spoken in Riau is known as Riau Hokkien, which is mutually intelligible to the Hokkien spoken by the Malaysian Chinese in Johor, southern Malaysia and Singapore. They are both derived from the Quanzhou dialect of Hokkien that originated from the city of Quanzhou in Fujian. Riau Hokkien is slightly mutually unintelligible with Medan Hokkien spoken in Medan since the latter is derived from the Zhangzhou dialect of Hokkien that originated from Zhangzhou, also in Fujian. Presently, Riau Hokkien has incorporated many words from the local language such as Malay and Indonesian.

Javanese is spoken by the Javanese people who migrated to the province. While several varieties of Batak is spoken by Batak immigrants from North Sumatra.

Religion

Religion in Riau[88]

Based on the composition of the population of Riau which is full of diversity with different socio-cultural, linguistic and religious backgrounds, it is basically an asset for the Riau region itself. The religions embraced by the inhabitants of this province are very diverse, including Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

As of 2015, Islam is the dominant religion in the province, forming 86.87% of the total population. Islam is generally adhered by the ethnic Malays, Javanese, Minangkabau, Banjars, Bugis, Sundanese and some Batak sub-group. Protestantism forms the second-largest religion, forming as many as 9.74%, while Catholics forms as many as 1.02%, Most of the people who adhered to Protestantism and Catholicism are from Batak ethnic groups (specifically Batak Toba, Karo and Simalungun), Nias, Chinese and residents from Eastern Indonesia. Then there is Buddhism which forms around 2.28% of the total population and Confucianism which forms around 0.07% of the total population. Most of the Buddhist and Confucianism are of ethnic Chinese origin. Lastly, about 0.01% of the total population embrace Hinduism, mostly are Balinese and Indonesians of Indian descent.

Culture

As Riau is the homeland of the Malays, the customs and cultures of Riau is mostly based on Malay customs and cultures.

Every Malay family lives in their own house, except for new couples who usually prefer to stay at the wife's house until they have their first child. Therefore, their sedentary patterns can be said to be neat. The nuclear family they called genitals generally built a house in the neighborhood where the wife lived. The principle of lineage or kinship is more likely to be parental or bilateral.

Kinship is done with a typical local nicknames. The first child is called long or sulung, the second child is ngah/ongah, below him is called cik, the youngest is called cu/ucu. Usually the nickname is added by mentioning the physical characteristics of the person, for example, if the person is dark-skinned and is a cik or a third child, he will be called cik itam. Another example is when the particular person is a first-born and has a short characteristic. he/she will be called ngah undah. But sometimes when greeting people who are unknown or new to them, they can simply greet them with abang, akak, dek, or nak.[89]

In the past, Malays also lived in groups according to their ancestral origin, which they called tribes. This group of descendants uses a patrilineal kinship line. But the Riau Malays who lived on the mainland Sumatra partially embraced matrilineal tribalism. There are also those who referthe tribe as a hinduk or a cikal bakal. Each tribe is led by a leader. If the tribe lives in a village, then the head will be referred to as Datuk Penghulu Kampung or Kepala Kampung.[90] Each leader is also assisted by several figures such as batin, jenang, tua-tua dan monti. Religious field leaders in the village are known as imam dan khotib.

Traditional dress

In Malay culture, clothes and textiles are very important and it signify beauty and power. The Hikayat-Hikayat Melayu mentioned the importance of textile in Malay culture.[91] The history of the Malay woven industry can be traced back to the 13th century when trade routes in the East are rapidly expanding under the role of the Song dynasty. The description of locally-made textiles and the development of the embroidery industry in the Malay Peninsula is expressed in several Chinese and Indian records.[91] Among the famous Malay textiles that still exist today are Songket and Batik.

The earliest Malay traditional dress was concise, the woman wearing a sarong that covered the lower body to the chest while the man dressed in short, sleeveless or shorts, with shorts down to the knee level. However, when trade with the outside world flourishes, the way in which the Malay dress begins to gain external influence and becomes more sophisticated. The 15th-century is the peak of the power of the Malacca Sultanate. As told in the Malay Annals, this is where traditional Baju Melayu clothing is created. The strong Islamic influence has transformed the way of dressing the Malays later on features that are matching with Islamic laws. The classic Malay general attire for men consists of shirts, small sacks, sarongs worn at the waist, and a tanjak or tengkolok worn on the head. It is common for a Malay warrior to have a keris tucked into the front fold of sarong. The Malay version of the early women's clothing is also more loose and long. However, it was subsequently renewed and popularized by Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor in the late 19th century, into the form of Baju Kurung used today.

However, Riau also has some traditional dress that cannot be found in other parts of the Malay world. The Riau traditional dress is not only used for certain occasions. But some of these traditional clothes are functioned as everyday clothes, one of which is daily clothing for children. The children's daily wear used is divided into two types, namely clothes for boys and clothes for girls. For boys' clothes in the customs of the Riau people, they are called baju monyet (Monkey clothes). This outfit is combined with the type of trousers that are responsible, and complete with a kopiah or rectangular shaped cloth as a head covering. While for everyday clothes for girls is Baju Kurung with floral motifs. This outfit is combined with a wide skirt with a hijab or tudong. The daily clothes of Riau people are commonly used for reciting or for studying.

For the people of Riau who are adults, they wear distinctive clothing and are also very close to religious and cultural values. For males, they use clothing called Baju Kurung Cekak Musang. Namely, clothes like Muslim clothing are combined with loose trousers. This shirt is used together with sarong and kopiah.

For Malay women, they can wear 3 different types of clothing, namely the Baju Kebaya Pendek, Baju Kurung Laboh, and Baju Kurung Tulang Belut. The different clothes are used in conjunction with a shawl cloth that is used as a head covering. In addition, women's clothing can also be combined with a hijab or tudong.

Traditional house

In traditional Malay societies, the house is an intimate building that can be used as a family dwelling, a place of worship, a heritage site, and a shelter for anyone in need. Therefore, traditional Malay houses are generally large. In addition to the large size, the Malay house is also always in the form of a rumah panggung or stage house, facing the sunrise. The types of Malay houses include residential houses, offices, place of worship and warehouses. The naming of the houses is tailored to the function of each building. In general, there are five types of Riau Malay traditional houses, namely the Balai Salaso Jatuh, Rumah Melayu Atap Lontik, Rumah Adat Salaso Jatuh Kembar, Rumah Melayu Lipat Kajang and Rumah Melayu Atap Limas Potong.

The Balai Salaso Jatuh is usually used for consensus decision-making and other activities. It is rarely used for private homes. In accordance with the functions of the Balai Salaso Jatuh, this building has other local names such as balai panobatan, balirung sari, balai karapatan, etc. Presently, the function of this building has been replaced by a house or a mosque. The building has an alignment, and has a lower floor than the middle room. In addition, Balai Salaso Jatuh is also decorated with various carvings in the form of plants or animals. Each carving in this building has its own designation.

Rumah Melayu Atap Lontik or Lontiok House can usually be found in Kampar Regency.[92] It is called so because this house has a decoration on the front wall of the house in the form of a boat.[92] When viewed from a distance, this house will look like boat houses that are usually made by the local residents. Besides being referred to as lancing and pancalang, this traditional house is also called lontik, since this house has a roof paring that is soaring upwards. This house is heavily influenced on the architecture of the Minangkabau Rumah Gadang, since Kampar Regency is directly adjacent to the province of West Sumatra. A unique feature of this traditional house is that it has five stairsteps. The reason they chose the number five was because this is based on the Five Pillars of Islam.[93] The shape of the pillars in this house also varies, there are rectangles, hexagons, heptagon, octagon and triangles. Each type of pole contained in this traditional house has meaning believed by the people of Riau. A rectangular pole can be interpreted as four corners of the wind, just like an octagon, and the hexagon symbolizes the number of pillars of Islam.

Rumah Salaso Jatuh Kembar was declared an icon and symbol of the province of Riau. The architecture of this house is similar to the Balai Salaso Jatuh, but this house tends to be used for private homes.

Rumah Melayu Lipat Kajang can usually found in the Riau Islands and the coastal part of Riau. It is called Lipat Kajangbecause the roof of this house has a shape resembling the shape of a boat. The top of this building is curved upwards and is often referred to lipat kejang or pohon jeramban by the locals. This traditional house is rarely or even no longer used by Riau residents. One reason for the loss of this culture is because of the increasing influence of western architecture, and people consider their building forms to be simpler and easier to build.[94]

Rumah Melayu Atap Limas Potong is a Malay traditional house that can usually be found in mainland Riau, but rarely in the Riau Islands. This house has a roof that is shaped like a cut pyramid. Like other Riau traditional houses, this house is also included in the rumah panggung group. The stage of this house has a height of about 1.5 meters above the ground. The size of the house depends on the ability and desires of the owner.[95]

Traditional dance

Most of Riau traditional dances are influenced by Malay cultures, but there are also some dances that are only unique to Riau.

Mak Yong is a traditional theater art of Malay society that is often performed as a drama in an international forum. In the past, mak yong was held by villagers in the rice fields which had finished harvesting rice. The mak yong is performed by a group of professional dancers and musicians who combine

various elements of religious ceremonies, plays, dance, music with vocal or instrumental, and simple texts. The male and female main characters were both performed by female dancers. Other figures that appear in the story are comedians, gods, jinn, courtiers, and animals. mak yong performance is accompanied by musical instruments such as rebab, gendang, and tetawak In Indonesia, the mak yong was developed in Lingga, which was once the center of the Johor-Riau Sultanate. The difference with the mak yong performed in the Kelantan-Pattani region is that they usually does not use masks, as mak yong in Riau uses masks for some of the King's female characters, princesses, criminals, demons, and spirits. At the end of the last century, mak yong not only became a daily show, but also as performance for the sultan.[96]

The tari zapin is a Malay traditional dance originated from the Siak Regency that is entertaining and are full of religious and educational messages. This tari zapin has rules and regulations that cannot be changed. Tari zapin is usually accompanied by traditional Riau musical instruments namely marwas and gambus. This tari zapin shows footwork quickly following the pounding of punches on a small drum called marwas . The rhythmic harmony of the instrument is increasingly melodious with stringed instruments. Because of the influence of the Arabs, this dance does indeed feel educative without losing the entertainment side. There is an insert of a religious message in the song lyrics. Usually the dance is told about the daily lives of Malay people. Initially, tari zapin was only danced by male dancers but along with developments, female dancers were also shown. Sometimes, there are both male and female dancers performing. There is a form of tari zapin performed in Pulau Rupat Utara in Bengkalis called tari zapin api. The identifying characteristic of tari zapin api is the incorporation of fire and strong focus on the mystical elements. The dance form was historically dormant and extinct for nearly 40 years before its revival in 2013.[97]

Tarian makan sirih is accompanied by distinctive Malay music accompanied by a song titled Makan Sirih. As for the costumes performed by dancers, they usually wore traditional Malay attire, such as pants, clothes, and kopiah for men. Whereas the female dancers wear the clothes that are usually worn by the bride, namely traditional clothes called the Baju Kurung teluk belanga. At the head, there is a crown equipped with flower-shaped decorations. Meanwhile, the lower part of the dancers' bodies was wrapped in brightly colored songket cloth. Tarian makan sirih is performed by both men and women. The dancers are obliged to understand special terms in Malay dance, such as igal (emphasizing hand and body movements), liuk (movement of bowing or swinging body), lenggang (walking while moving hands), titi batang (walking in a line as if climbing the stem), gentam (dancing while stomping on the feet), cicing (dancing while jogging), legar (dancing while walking around 180 degrees), and so on. During the performance, one of the dancers in the offering dance will bring a box containing betels. The box would then be opened and the guests who are considered the greatest are given the first opportunity to take it as a form of respect, then followed by other guests. Therefore, many people call this dance as tarian makan sirih.[98]

Traditional music

There are several musical instruments in Riau that is used for ceremonial events.

The traditional Malay accordion is almost the same as the accordion founded by Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann from (Germany). accordion includes a musical instrument that is quite difficult to play even though it looks easy. accordion produces diatonic scales that are very in accordance with the song lyrics in the form of rhymes. The accordion player holds the instrument with both hands, then plays the chord buttons with the fingers of the left hand, while the fingers of the right hand play the melody of the song that is being performed. Usually players who have been trained are very easy to change hands. When played, the accordion is pulled and pushed to adjust the air movement inside the instrument, the movement of the air coming out (to the tongue of the accordion) will produce sound. The sound can be adjusted using the player's fingers.

Gambus is a type of traditional Riau musical instrument that is played by picking. Formerly, Gambus was used for events related to spiritual matters. At this time Gambus switched functions to be an accompaniment for the tari zapin. Gambus Riau is played by individuals as entertainment for fishermen on boats who are looking for fish.

Kompang is a type of traditional Riau musical instrument that is quite well known among Malays, Kompang is included in the group of traditional musical instruments which are played by being beaten. In general, kompang uses materials derived from the skin of livestock. Making kompang is more similar to making dhol or other musical instrument or other leather drum that uses animal skin such as buffalo, cattle, and others. Kompang a uses female goat ski on the part that is hit, but now uses a cow which is believed to be more elastic. To produce a loud sound, there is a technique to make the paired skin become very tight and not easily separated from the nail (which can be dangerous when played).

Rebana ubi is a type of Tambourine that is played by being hit by hand. Rebana ubi is included in the drum group as well as percussion instruments. Rebana ubi has a larger size than ordinary tambourines because Rebana ubi has the smallest diameter of 70 cm and a height of 1 meter. Rebana ubi can be hung horizontally or left on the floor to be played. In ancient times, Rebana ubiwas believed to be a tool to spread the news such as the wedding ceremony of local residents or the danger that came (such as strong winds). Rebana ubi is placed in the highlands and beaten with a certain rhythm depending on the information the player wants to convey.

Traditional weapons

Klewang is a traditional weapon from Riau. klewang is a kind of machete with the tip of an enlarged blade. In the past, klewang was used by royal soldiers when in war. However, in the present, it is more widely used by farmers in their activities in rice fields or as agricultural tools. Because of this function, klewang has remained sustainable compared to other types of traditional Riau weapons.

Beladau is a skewer type weapon found in the culture of Riau society. This weapon is a sharp dagger on one side. what makes this beladau different from the dagger in general is that beladau tends to have curvature at the base of the handle, so the handle is easier to hold and push when used. In accordance with its length of only 24 cm, this traditional Riau weapon is often used as a means of self-protection from melee attacks.

Pedang jenawi is a weapon that was often used by Malay royal warlords when facing their enemies. Its size is quite long, which is about 1 meter making it used in close-range warfare. At a glance, pedang jenawi looks like a typical Japanese katana. Therefore, many historians and cultural experts argue that this weapon originated from ancient Japanese culture which experienced acculturation with Malay culture. Apart from these opinions, what is clear at this time is that pedang jenawi has been regarded as the identity of the Riau Malay community.

Kris is a heritage weapon that has been used for centuries. Not only in Riau, keris is generally used by nobles in Southeast Asia. Kris is a symbol of honor and self-defense. This weapon is used to stab at close range. The position of the kris in history as a symbol of honor is undeniable, that in the kingdom it was clearly seen as a form of self-protection, as well as pride. Even in modern history, the function continues to develop as an object of history, and can also be a determinant of history based on the period of manufacture and the type of material used. Up to now in Riau Malay customs and culture, always cooperating with kris in every dress as a complementary weapon from generation to generation. However, what is different in the form of kris from adat in Java is, if the use of kris in Java is tucked in the back of the waist, in Riau and the Malay people, in general, the use of kris is in front.

Economics

Riau GDP share by sector (2022)[99]

The economy of Riau expands faster (8.66% in 2006) than the Indonesian average (6.04% in 2006), and is largely a resource-based economy, including crude oil (600,000 bpd), palm oil, rubber trees and other forest products. Local government income benefits from a greater share of tax revenue (mainly from crude oil) due to the decentralisation law of 2004.[100] The province has natural resources, both riches contained in the bowels of the earth, in the form of oil and gas, as well as gold, as well as forest products and plantations. Along with the implementation of regional autonomy, gradually began to apply the system for results or financial balance between central and local. The new rules provide expressly limits the obligations of investors, resource utilization, and revenue-sharing with the surrounding environment.

Riau's economy in the first quarter of 2017 grew by 2.82 per cent, improving compared to the same period in the previous year which grew 2.74 per cent (year-over-year). This growth was supported by growth in almost all businesses, except mining and excavation which contracted 6.72 per cent. The highest growth occurred in the Corporate Services Business Field at 9.56 per cent, followed by the processing Industry of 7.30 per cent, and government administration, defense and obligatory social security of 6.97 per cent. Riau's economy in the first quarter of 2017 contracted by 4.88 per cent compared to the fourth quarter of 2016. This contraction was influenced by seasonal factors in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Business Field (−5.04 per cent). In addition, contractions occur due to a decrease in several business fields, including: Mining and Excavation (−3.50 per cent); Processing Industry (−5.41 per cent); Large Trade and Retail, Car and Motorcycle Repair (−2.46 per cent); and Construction (−8.94 per cent).[101]

Energy and natural resources

The energy and mineral resources sector is one sector that plays a major role in the development of the province. The leading commodities in the energy and mineral resources sector in Riau include electricity and mining.[103]

Electricity is an important commodity for human life at this time. Without electricity, almost certainly many construction sectors will be paralyzed. Most of the electricity in Riau Province is still supplied by the Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN).

From 2013 to 2015, the electricity capacity produced was 114 Kva/Kwh in hydropower, 94.6 Kva/Kwh in diesel power and 131.2 Kva/Kwh in the gas power. The amount of this electricity capacity does not increase or shrink as well as the number of power generating units. Throughout Riau Province there are 1 unit of hydroelectric power plants, 65 units of diesel power plants and 6 units of gas power plants.[103]

Farming

The agricultural sector is also one of the factors that play a role in the economic development of Riau. The main commodities of agriculture are rice, corn and soybeans. In addition, other agricultural products which are commodities of Riau Province are peanuts, green beans, cassava and sweet potatoes. In 2015, rice production in Riau reached 393,917 tons of milled dry grain. The production was calculated to increase by 2.2 per cent compared to production in 2014. The increase in production was influenced by the increase in the harvested area of 107,546 hectares which increased by around 1,509 hectares (1.42%) compared to the previous year. In addition, rice productivity also increased by around 0.26 quintal / hectare or around 0.71%.[103]

While the increase occurred in corn production, which amounted to 30,870 tons of dry shelled rice, this production increased by around 7.75 per cent or 2,219 tons of dry shelled rice. This increase can be affected because of an increase in the area of maize production by 368 hectares (3.1%) compared to the production area in 2014 of 12,057 hectares. The increase also occurred in corn productivity in 2015 amounting to 1.09 quintal / hectare from 2014 or around 4.59%.[103]

Soybean production also decreased in 2015 by 187 tons of dry beans (8.02%) from soybean production in 2014. The decrease in production was influenced by the harvested area of 1,516 hectares which decreased by around 514 hectares (25.32%). However, soybean productivity increased by 2.66 quintal / hectare or 23.15% compared to the previous year.

In 2015, peanut production was lower than in previous years. This production fell by 8.39 per cent compared to 2014 and 16.65 per cent compared to 2013. The decline in production was influenced by the declining area of peanut farming compared to 2013 and 2014, each of 18.41 per cent and 9.23 per cent .[103]

In 2015, green beans production was lower than in previous years. This production fell by 7.28 per cent compared to 2014 and 3.39 per cent compared to 2013. The decline in production was influenced by the decline in the area of green beans compared to 2013 and 2014, respectively 1.53 per cent and 3.67 per cent.[103]

In addition, cassava production also experienced a decline in 2015 of 11.89 per cent compared to 2014. Actually, cassava production had increased in 2014 by 14.08 per cent. This decrease in production was also influenced by the decline in cassava farming area by 11.61 compared to 2014.

In the last three years, sweet potato production in 2015 was the lowest. This yield fell by 5.36 per cent in 2014 and again fell by 18.05 per cent. As before, the decline in production was also influenced by the declining area of sweet potato farming by 4.96 per cent in 2014 and 18.83 per cent in 2015.[103]

Fishing

One of Riau's leading commodities is the fisheries sector. The geographical condition of Riau where 17.40% of the total area is an oceanic area and there are 15 rivers making the fisheries sector well developed. In addition, the vast extent of untapped land is a great potential for inland aquaculture to develop. In addition, the market demand for fishery products has increasingly made the catchment sector not enough so that fish farming activities such as cages, ponds, public fisheries and ponds are well developed.[103]

Riau fisheries production mostly comes from marine fisheries. In 2015, the data showed that marine fisheries were 106,233.1 tons or decreased 1 per cent from the previous year. In addition, the number of fishery households decreased to 14,610 households, an increase of 0.98 per cent. In addition, there was also a decline in the number of fishing vessels as many as 123 units.

The land fishery product processing industry can be divided into four types, namely floating nets, ponds, public fisheries and ponds. In 2015, fish production from floating nets was 5,378.56 tons or decreased by 82.52 per cent. This decrease was caused by a decrease in the number of floating nets as many as 157,638 units. Fish production in public fisheries also decreased by 3.9 per cent due to a decrease in the number of households. Fish pond production increased by 5,425.2 tons or 10.8 per cent. Temporary data on fish pond production showed a drastic decrease of 82.23 per cent even though the number of fish ponds increased by 89.15 hectares compared to 2014.[103]

Stockbreeding

Along with increasing public consumption needs for livestock products, both in terms of consumption of livestock meat and other livestock products, such as milk and eggs, the Riau provincial government through the Agriculture and Livestock Service Office continues to try to meet these needs. In addition to the commitment of Riau province to increase food self-sufficiency in 2020, the number of animal populations continues to be increased to meet consumption needs. This is reflected in the increase in some aspects of livestock in Riau in the last 3 years.[103]

Agriculture and plantation

Plantation growing is rubber and oil palm plantations, either run by the state or by the people. There is also a citrus and coconut plantations. For oil palm plantation area currently Riau province has a land area of 1:34 million hectares. In addition there have been about 116 palm oil mills (PKS) which operates with the production of coconut palm oil (CPO) 3.3868 million tons per year.

Industry

In this province there are several international companies engaged in the oil and gas as well as the processing of forest products and oil. In addition there is also a copra and rubber processing industry. Several major companies including Chevron Pacific Indonesia a subsidiary of Chevron Corporation, PT. Indah Kiat Pulp & Paper Tbk in Perawang, and PT. Riau Andalan Pulp & Paper in Pangkalan Kerinci Riau provincial mining. Minerals are petroleum, gas, and coal.

Finance and banking

In the field of banking in the province is growing rapidly, this marked the number of private banks and rural banks, in addition to local government-owned banks such as Bank of Riau Kepri.

Transportation

Sultan Syarif Kasim II International Airport in Pekanbaru is the largest airport in the province. It serves as the gateway to Pekanbaru and Riau in a whole. The airport serves flights to other major cities in Indonesia such as Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung and Medan. Moreover, the airport also serves international flights to cities neighbouring countries such as Singapore, Malacca and Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. Furthermore, the airport also was used for hajj embarkation to Jeddah and Medina in Saudi Arabia. On 16 July 2012, a Rp 2 trillion ($212 million) new terminal has been opened to accommodate 1.5 million passengers a year.[104] The new terminal spanning 17,000 square meters and a more spacious aircraft apron which can accommodate 10 wide-body aircraft, twice the capacity of the old apron. The new terminal is designed with a mix of Malay and modern architecture. The physical form of the building is inspired from the typical flying fauna form of Riau, Serindit birds. To meet the technical requirements of a world-class airport, the airport runway is extended from 2,200 meters to 2,600 meters and then to 3,000 meters.[105] There are other smaller airports in Riau which mostly serves regional or charter flights, such as Pinang Kampai Airport in Dumai, Tuanku Tambusai Airport in Pasir Pangaraian, Japura Airport in Rengat, Sei Pakning Airport in Tembilahan, Sei Pakning Airport in Sungai Pakning and Sultan Syarief Haroen II Airport in Pangkalan Kerinci.

- Transportation in Riau

Tanjung Buton Ferry Harbor in Siak Regency

Tanjung Buton Ferry Harbor in Siak Regency Siak Bridge

Siak Bridge Road conditions in Bangkinang

Road conditions in Bangkinang

The Trans-Sumatran Highway runs along the length of the province. Riau serves as a junction of the highway, with North Sumatra to the north, Jambi to the south and West Sumatra to the west. Most of the roads have been paved, but there are some sections that is in poor condition. Road damage was allegedly due to the large number of trucks carrying palm oil crops passing from Riau to North Sumatra or vice versa.[106] As part of the Trans-Sumatra Toll Road program, the government is currently constructing the 131,48 km long Pekanbaru–Dumai Toll Road, which would connect Pekanbaru, the provincial capital and the port city of Dumai on the Strait of Malacca.[107] The first section between Pekanbaru and Minas is expected to begin operation in December 2019 and the whole toll road is expected to begin operation in 2020.[107][108] Another toll road connecting Pekanbaru and Padang in West Sumatra is also under the planning stage. Construction is expected to start on the Riau side due to land clearing issue on the West Sumatran side.[109] The project would also include the construction of the construction of an 8.95 km tunnel in the Payakumbuh area that will penetrate the Bukit Barisan Mountains, which would be the longest tunnel in Indonesia.[110]

The Port of Dumai is the largest port in the province. It serves both passengers and cargo. The port serves ferries to Batam and Tanjung Pinang in the Riau Islands, as well as international destinations such as Singapore, Johor and Malacca in Malaysia. River transportation is also important in Riau, as the province is crossed by many large rivers.

After the Pekanbaru Railway was abandoned at the end of World War II, there is currently no active railway line in Riau. However, there has been a proposal of reactivating the Pekanbaru-West Sumatra railway to connect Pekanbaru and Padang on the western coast of Sumatra, as well as building the Pekanbaru-Duri-Rantau Prapat railway which would connect Riau and the existing railway line in North Sumatra, as well as building the Pekanbaru-Jambi-Betung-Palembang railway which would connect Riau with Jambi and th existing railway line in South Sumatra. Overall, this railway system would form the Trans-Sumatra Railway.[111]

Tourism

The prime tourist attractions of Riau can be divided into natural environment, as well as the culture and history of the Riau Malay people.

Tourist attractions in Riau are diverse, ranging from marine tourism, because of the location of Riau which is directly facing the Strait of Malacca. The province has a long history and is present throughout the province, thus making its historical and cultural tourism diverse and well-known. Each of the regencies in Riau has a tourist attraction within.

The Indragiri Hilir Regency has a long history before the Dutch colonial period, with a series of power shifts starting from the Keritang Kingdom (c. 6th century AD), Kemuning Kingdom, Batin Enam Suku Kingdom to the Indragiri Kingdom. The Indragiri Hilir Regency also has a number of tourist attractions, and among them is Solop Beach which is a mainstay tourist attraction in Riau. As Indragiri Hilir was once the seat of the Indragiri Sultanate, there are many remnants from the sultanate than can be still found throughout the region, such as the Indragiri Kings Cemetery in Rengat and traditional houses with typical Malay architecture. Moreover, Indragiri Hilir is also known for its many waterfalls. Similar to Indragiri Hilir, the Indragiri Hulu Regency is filled of many tourism spots, such as waterfalls and remnants of ancient Malay kingdoms. Furthermore, Indragiri Hulu also serves as the gateway to the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park.

The location of Kampar Regency which is directly adjacent with the province of West Sumatra allows its culture to be greatly influenced by the culture of the Minangkabau people. Kampar Regency also has some famous and historical attractions, such as the Muara Takus Buddhist Temple.[112] There are also many spectacular waterfalls spread throughout Kampar. Moreover, there are also tombs of Malay and Minangkabau kings in Kampar. The city of Bangkinang has many tourist attractions that have nuances of nature, history, religion and culinary that cannot be found in any parts of Indonesia.

The Kepulauan Meranti Regency has a variety of marine tourism destinations. Therefore, making it one of the biggest contributors to tourist attractions in Riau that attract both domestic and international tourists each year. The capital Selat Panjang has a Chinese-majority population, making it one of the few cities to have this characteristic. This explains why the culture of Selat Panjang as well as the whole of Kepulauan Meranti is highly influenced by both Chinese and Malay culture. Moreover, there are several Chinese temples that can be found in Selat Panjang and the surrounding area, including the Hoo Ann Kiong Temple, which is the oldest Chinese Taoist temple in Selat Panjang.[113]

Kuantan Singingi Regency, commonly known as Kuansing, is a rantau (migration) area for the Minangkabau people from West Sumatra. Therefore, the culture and customs of Kuansing is highly influenced by Minangkabau culture. On the other hand, Kuansing also contains many tourist destinations. Kuansing is known for its cultural festival that usually happens during the Eid al-Fitr and other holidays such as the Baganduang Boat Festival (Indonesian: Festival Perahu Baganduang). The Baganduang Boat Festival was first held as a festival in 1996.[114] These boats are then decorated with flags, coconut leaves, umbrellas, long cloths, pumpkins, photos of the president and vice president, and other objects that have traditional symbols. For example, rice symbolizes agricultural fertility and buffalo horns that symbolize livestock. In the festival, guests were presented with a variety of entertainment, including Rarak Calempong, Panjek Pinang, and Potang Tolugh. The process of making a baganduang boat is usually blessed with a Malay ceremony. Another festival in Kuansing is the Pacu Jalur Festival. Pacu Jalur is the largest annual festival for the people of the Kuantan Singingi Regency, especially in the capital, Taluk Kuantan, which is along the bank of the Kuantan River. Originally, the festival was held to commemorate the Islamic holidays such as the Mawlid, or the commemoration of the New Year's Eve. But after the Indonesian independence, Pacu Jalur is now usually held to celebrate the Independence Day of the Republic of Indonesia.[115] Pacu Jalur is a long rowing boat race, similar to the Dragon Boat race in neighboring Malaysia and Singapore, which is a boat or canoe made of wood that can reach 25 to 40 meters in length. In the Taluk Kuantan area, the native people called the longboat used in the festival as Jalur. The boat rower team ranges from 50 to 60 people.[116]

Pelalawan Regency has a long history, even as the name Pelalawan was taken from the name of the former Pelalawan Kingdom. And the Pelalawan Kingdom was once victorious in 1725 and was very famous with its Sultan Syed Abdurrahman Fachrudin. Apart from its history, Pelalawan also stores quite a lot of tourist attractions besides its history. Remnants of the old Pelalawan Kingdom can still be seen throughout the regency, such as Sayap Pelalawan palace where the former Sultan of Pelalawan reside. Inside the Pelalawan Wing Palace there are many relics, such as keris weapons, spears, and various other relics placed in the palace central room.[117] Another remnants is tomb of the sultans of Pelalawan. Most of the tourist who frequented the tomb are usually pilgrims and certain days the tomb is quite crowded with pilgrims.[118] Moreover, Pelalawan serves as the gateway to the Tesso Nilo National Park.

Rokan Hilir Regency as one of the regencies in Riau which is directly facing the Strait of Malacca, was once the largest fish producer in Indonesia. Since the Dutch colonial era, Rokan Hilir with its capital Bagansiapiapi has already become more advanced than other region especially in terms of trade. The tourism industry in Rokan Hilir is also quite well known both on a national and international scale. Rokan Hilir is known for its tourist spots and festival such as the Junk burning festival. Known in the local Riau Hokkien as Go Gek Cap Lak,[lower-alpha 1] the Junk burning festival is an annual ritual of the community in Bagansiapiapi which has been well known overseas and is included in the Indonesian tourism tourist. Every year this ritual can attract tourists from Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan to Mainland China. Now this annual event is heavily promoted by the government of Rokan Hilir Regency as a source of tourism.[119] The initial history of the festival was started by Chinese people who lived in Bagansiapiapi to commemorate their ancestors and also as a gesture of gratitude to the God Kie Ong Ya.[120] Other than that, Bagansiapiapi and the surrounding area has many Chinese temples that can be visited.

The Rokan Hulu Regency has the nickname Negeri Seribu Suluk. The district is bordered by two provinces, namely North Sumatra and West Sumatra. It is certain that the acculturation of culture in Rokan Hulu Regency has become more diverse, starting from customs and traditions. Rokan Hulu contains many lakes, waterfalls and caves that is spread throughout the region. One of the historical assets that is still standing firmly in Rokan Hulu, is the Palace of Rokan Hulu. This palace, which is already 200 years old, is a relic of the Nagari Tuo Sultanate. Although there are some parts of the repair but the architecture is still intact and also the carvings on the wood are still clearly visible.[121]

Siak Regency is the number two richest district in Riau after Bengkalis Regency. The main export of Siak Regency is petroleum which finally can deliver it to become the second richest regency in the province. On the other hand, the regency is currently boosting the tourism sector to attract more visitors. As Siak was once the house of the Sultanate of Siak Sri Indrapura, the regency contains remnants of the sultanate that is still well-preserved, such as the Siak Sri Indrapura Palace. The palace complex has an area of about 32,000 square meters consisting of 4 palaces namely Istana Siak, Istana Lima, Istana Padjang, and Istana Baru. Each of the palace including Siak Palace itself has an area of 1,000 square meters.[122] The palace contains royal ceremonial objects, such as a gold-plated crown set with diamonds, a golden throne and personal objects of Sultan Syarif Qasyim and his wife, such as the Komet, a multi-centennial musical instrument which is said to have been made only two copies in the world.[123] Presently, the komet is still functioning and is used to play works by composers such as Beethoven, Mozart and Strauss. Siak is also home to the tomb of Sultan Syarif Kasim II, the last Sultan of Siak.

Dumai is a city located in Riau whose location is very strategic especially for international trade because of its location in the Strait of Malacca. In addition, Dumai is the largest city in Indonesia at this time. Dumai is home to many beaches and mangrove forests.