South Papua

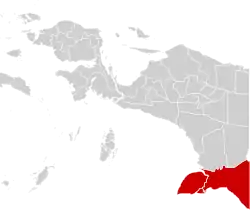

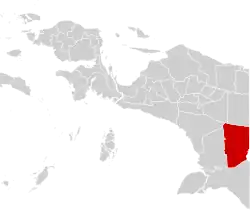

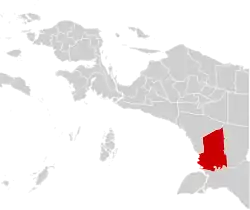

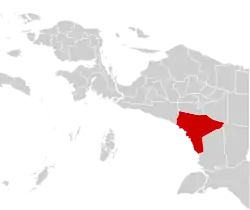

South Papua, officially the South Papua Province (Indonesian: Provinsi Papua Selatan),[4] is an Indonesian province located in the southern portion of Papua, following the borders of Papuan customary region of Anim Ha.[5][6] Formally established on 11 November 2022 and including the four most southern regencies that were previously part of the province of Papua and before 11 December 2002 were all part of a larger Merauke Regency, it covers an area of 117,849.16 km2 . It had a population of 522,215 according to the official estimates for mid 2022,[2] making it the least populous province in Indonesia.

South Papua

Papua Selatan | |

|---|---|

| Province of South Papua | |

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): | |

| |

OpenStreetMap | |

| Capital | Salor, Merauke Regency |

| Government | |

| • Body | South Papua Provincial Government |

| • Acting Governor | Apolo Safanpo |

| • Vice Governor | Vacant |

| Area | |

| • Total | 117,849.16 km2 (45,501.82 sq mi) |

| Population ([2]) | |

| • Total | 522,215 |

| • Density | 4.4/km2 (11/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official language | Indonesian |

| • Native languages of South Papua | Asmat, Boazi, Citak, Kolopom, Korowai, Marind, Mombum, Muyu, Wambon, Yaqay, and others |

| • Also spoken | Javanese, Papuan Malay, and others |

| Demographics | |

| • Religions |

|

| • Ethnic groups | Asmat, Kombai, Korowai, Marind, Marori, Sawi, Wambon (natives), Javanese (migrant), and others |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Indonesia Eastern Time) |

| Website | papuaselatan |

It shares land borders with the sovereign state of Papua New Guinea to the east, as well as the Indonesian provinces of Highland Papua and Central Papua to the north and northwest, respectively. South Papua also faces the Arafura Sea in the west and south, which is maritime border with Australia. The province comprises the Papuan customary region of Anim Ha.[7] Merauke is the economic centre of South Papua, while its capital is Salor located in Kurik district, Merauke Regency, around 60 km from Merauke.[8]

History

The wetland region of South Papua, prior to the arrival of Europeans, was home to several indigenous tribes. These tribes included the Asmat, Marind, and Wambon, who still maintain their ancestral traditions in the area. The Marind tribe, also known as the Malind, lived in groups along the rivers in the Merauke region, and their way of life centered around hunting, gathering, and farming. However, the Marind tribe was also notorious for their practice of headhunting. They would travel in boats along the rivers and coasts to distant settlements, where they would behead the inhabitants. The heads of their victims would then be taken back to their villages to be preserved and celebrated.[9][10][11]

In the 19th century, European powers began to colonize the island of New Guinea. The island was divided along a straight line, with the western portion falling under the jurisdiction of the Dutch New Guinea region and the eastern portion becoming British New Guinea. Marind people often crossed the border to engage in headhunting activities. In 1902, the Dutch established a military base at the eastern tip of South Papua, near the Maro River, to strengthen the border and eliminate this tradition. This base was named Merauke, after its location. The Dutch also established a Catholic mission in Merauke in an effort to spread their religion and to further discourage the practice of headhunting. During the Dutch colonial period, the Javanese people were brought to Merauke to cultivate rice fields. This influx of laborers further contributed to the growth of the town and the development of the surrounding region. Eventually, it became the capital of Afdeeling Zuid Nieuw Guinea, or the South New Guinea Province.[9][11]

In addition to the Maro River, the Dutch also became aware of another, larger river known as the Digul River. In the 1920s, the Dutch government sent an expedition to explore the interior of Papua. The idea emerged to use the remote region as a detention camp, and a suitable location was identified at the headwaters of the Digul River or Boven Digoel. A camp called Tanah Merah was established, it was a dense forested area surrounded by the harsh Digul River, making it difficult for prisoners to escape. Additionally, the region was plagued by malaria, which further discouraged attempts at escape. Over the years, several notable figures were detained at the camp, including Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir. After the Dutch left in the 1960s, Tanah Merah became more populated and eventually became the capital of the Boven Digoel Regency.[11][12][13]

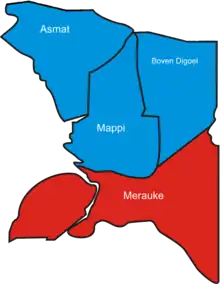

In the 1960s, Indonesian forces took control of all of Dutch New Guinea, including the former Zuid Nieuw Guinea. Following the takeover, the territory was reorganized, and the former Zuid Nieuw Guinea became the Merauke Regency, with its capital located in Merauke. In 2002, the Merauke Regency was further divided into four separate regencies: Merauke, Mappi, Asmat, and Boven Digoel. These regencies were established to better serve the needs of the local populations and provide more effective governance across the region. More recently, on 25 July 2022, the former territory of the Merauke Regency was officially re-united with other regions in southern Papua to form the new province of South Papua, following the signing of Law No. 14/2022. The name "South Papua" was chosen instead of "Anim Ha" due to the latter term's historical origins during Dutch rule and its potential to be demeaning to other tribes in southern Papua. In contrast, "South Papua" was selected as an inclusive and unifying name that avoids any negative connotations and reflects the diverse and vibrant cultural heritage of the region.[4] The public reception towards South Papua was far more positive compared to the other new provinces of Central Papua and Highlands Papua,[14] with local residents spreading a giant Indonesian flag in front of the regent office of Merauke after the province's establishment.[15]

Politics

Administrative division

South Papua is divided into four regencies (kabupaten), the least amount compared to other Indonesian provinces. Before 11 December 2002 all four of the current regencies comprised a single Merauke Regency, which was split into the present four regencies on that date. The table below gives the areas of all the regencies,[16] together with their populations at the 2020 Census[17] and according to the official estimates as at mid 2022.[2]

| Kode Wilayah |

Name of Regency |

Seat | Regent | Area in km2 |

Pop'n Census 2020 |

Pop'n Estimate mid 2022 |

HDI | No. of districts |

No. of villages |

Coat of arms |

Location map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93.01 | Merauke Regency | Merauke | Romanus Mbaraka | 45,013.35 | 230,932 | 232,357 | 0.701 (High) | 20 | 190 |  pus |

|

| 93.02 | Boven Digoel Regency | Tanah Merah | Hengky Yaluwo | 23,558.27 | 64,285 | 65,193 | 0.615 (Medium) | 20 | 112 |  pus |

|

| 93.03 | Mappi Regency | Kepi | Krisostomus Yohanes Agawemu |

24,262.23 | 108,295 | 111,141 | 0.582 (Medium) | 15 | 164 |  pus |

|

| 93.04 | Asmat Regency | Agats | Elisa Kambu | 25,015.31 | 110,105 | 113,524 | 0.506 (Low) | 19 | 221 |  pus |

|

Totals |

117,849.16 | 513,617 | 522,215 | 74 | 687 |  | |||||

Culture

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 160,727 | — |

| 1980 | 172,662 | +7.4% |

| 1990 | 243,722 | +41.2% |

| 2000 | 291,680 | +19.7% |

| 2010 | 409,735 | +40.5% |

| 2020 | 513,617 | +25.4% |

| 2022 | 522,215 | +1.7% |

| Source: Statistics Indonesia 202and earlier. South Papua part of Papua Province until 2022 | ||

The native Papuan people has a distinct culture and traditions that cannot be found in other parts of Indonesia. Coastal Papuans are usually more willing to accept modern influence into their daily lives, which in turn diminishes their original culture and traditions. Meanwhile, most inland Papuans still preserves their original culture and traditions, although their way of life over the past century are tied to the encroachment of modernity and globalization.[18] Each Papuan tribe usually practices their own tradition and culture, which may differ greatly from one tribe to another.

One of the most well-known Papuan tradition is the stone burning tradition (Indonesian: Tradisi Bakar Batu), which is practiced by most Papuan tribes in the province. The stone burning tradition is an important tradition for all indigenous Papuans. For them, is a form of gratitude and a gathering place between residents of the village. This tradition is usually held when there are births, traditional marriages, the coronation of tribal chiefs, and the gathering of soldiers. It is usually carried out by indigenous Papuan people who live in the interior, such as in the Baliem Valley, Paniai, Nabire, Pegunungan Bintang, and others. other. The name of this tradition varies in each region. In Paniai, the stone burning tradition is called Gapiia. Meanwhile, in Wamena it is called Kit Oba Isogoa, while in Jayawijaya it is called Barapen. It is called the stone burning tradition because the stone is actually burned until it is hot. The function of the hot stone is to cook meat, Sweet potatoes, and vegetables on the basis of banana leaves which will be eaten by all residents at the ongoing event.[19][20] In some remote Papuan communities who are Muslim or when welcoming Muslim guests, pork can be replaced with chicken or beef or mutton or can be cooked separately with pork. This is, for example, practiced by the Walesi community in Jayawijaya Regency to welcome the holy month of Ramadan.[21]

Hunting as practiced by Marind people usually begin by traditional controlled burn of peatbog and swamps, it was then left for three days to a week for new shoots to grow, which will invite game animals such as deer, pigs, saham (kangaroos). Hunting party consisting of usually of 7-8 people, then go to the burned locations while bringing food and drink, ranging from tubers, sago, to drinking water, for several days. Temporary hut called bivak would be constructed from barks from Bus, a type of eucalyptus trees to form the walls and the roof made from Lontar leaves.[22] As with many coastal communities from Moluccas to Papua, Sasi is practiced, which are markers usually constructed from wood and janur to mark the prohibition of harvesting either from land or sea for a period of time with the goal to preserve natural resources and for sustainable harvest.[23] To open and close sasi regions such as forest, usually the Marind-Kanume mark with two arrows shot to the west and to the east to respect three clans that inhabited the area as well as other rituals which can take up to forty days. Violators of the prohibition would be punished with payment of Wati leaves and pigs. Failure of payments, will result in referral to local security officers to be put on trial.[24]

Architecture

The Korowai people from the Mappi Regency in southern Papua is one of the indigenous tribes in Papua that still adheres to the traditions of their ancestors, one of which is to build houses on top of trees.[25][26] The Korowai people is one of the indigenous tribes in the interior of Papua that still maintains firmly the traditions of their ancestors, one of which is to build a house on a tall tree called Rumah Tinggi (lit. 'high house'). Some of the Korowai people's tree houses can even reach a height of 50 m above the ground. The Korowai people builds houses on top of trees to avoid wild animals and evil spirits. The Korowai people still believes in the myth of Laleo, a cruel demon who often attacks suddenly. Laleo is depicted as an undead that roams at night. According to the Korowai people, the higher the house, the safer it will be from Laleo's attacks. The rumah tinggi is built on big and sturdy trees as the foundation for its foundation. The tops of the trees are then deforested and used as houses. All materials come from nature, logs and boards are used for the roof and floor, while the walls are made of sago bark and wide leaves. The building process for a rumah tinggi usually takes seven days and lasts up to three years.[26]

Cuisine

The native Papuan food usually consists of roasted boar with Tubers such as sweet potato. The staple food of Papua and eastern Indonesia in general is sago, as the counterpart of central and western Indonesian cuisines that favour rice as their staple food.[27] Sago is either processed as a pancake or sago congee called papeda, usually eaten with yellow soup made from tuna, red snapper or other fishes spiced with turmeric, lime, and other spices. On some coasts and lowlands on Papua, sago is the main ingredient to all the foods. Sagu bakar, sagu lempeng, and sagu bola, has become dishes that is well known to all Papua, especially on the custom folk culinary tradition on Mappi, Asmat and Mimika. Papeda is one of the sago foods that is rarely found.[28] As Papua is considered as a non-Muslim majority regions, pork is readily available everywhere. In Papua, pig roast which consists of pork and yams are roasted in heated stones placed in a hole dug in the ground and covered with leaves; this cooking method is called bakar batu (burning the stone), and it is an important cultural and social event among Papuan people.[29] The Marind people used this cooking method or using burning bomi thermite mound made by Macrotermes sp to cook a pizza-like dish called "Sagu Sef", which is made from dough from sago and coconut with sago grub and deer meat. Spices used can include shallot, garlic, coriander, pepper, and salt, which then mixed and covered with banana leaves, to cook it evenly hot stones or bomi would be put on top of the dish.[30]

In the coastal regions, seafood is the main food for the local people. One of the famous sea foods from Papua is fish wrap (Indonesian: Ikan Bungkus). Wrapped fish in other areas is called Pepes ikan. Wrapped fish from Papua is known to be very fragrant. This is because there are additional bay leaves so that the mixture of spices is more fragrant and soaks into the fish meat. The basic ingredient of Papuan wrapped fish is sea fish, the most commonly used fish is milkfish. Milkfish is suitable for "wrap" because it has meat that does not crumble after processing. The spices are sliced or cut into pieces, namely, red and bird's eye chilies, bay leaves, tomatoes, galangal, and lemongrass stalks. While other spices are turmeric, garlic and red, red chilies, coriander, and hazelnut. The spices are first crushed and then mixed or smeared on the fish. The wrapping is in banana leaves.[31] Udang selingkuh is a type of prawn dish native to Wamena and the surrounding area. Udang selingkuhis usually served grilled with minimal seasoning, which is only salt. The slightly sweet natural taste of this animal makes it quite salty. The serving of Udang selingkuh is usually accompanied by warm rice and papaya or kale. It is usually also served with the colo-colo sambal combination which has a spicy-sweet taste.[32]

Common Papuan snacks are usually made out of sago. Kue bagea (also called sago cake) is a cake originating from Ternate in North Maluku, although it can also be found in Papua.[33] It has a round shape and creamy color. Bagea has a hard consistency that can be softened in tea or water, to make it easier to chew.[34] It is prepared using sago,[35] a plant-based starch derived from the sago palm or sago cycad. Sagu Lempeng is a typical Papuan snacks that is made in the form of processed sago in the form of plates. Sagu Lempeng are also a favorite for travelers. But it is very difficult to find in places to eat because this bread is a family consumption and is usually eaten immediately after cooking. Making sago plates is as easy as making other breads. Sago is processed by baking it by printing rectangles or rectangles with iron which is ripe like white bread. Initially tasteless, but recently it has begun to vary with sugar to get a sweet taste. It has a tough texture and can be enjoyed by mixing it or dipping it in water to make it softer.[36] Sago porridge is a type of porridge that are found in Papua. This porridge is usually eaten with yellow soup made of mackerel or tuna then seasoned with turmeric and lime. Sago porridge is sometimes also consumed with boiled tubers, such as those from cassava or sweet potato. Vegetable papaya flowers and sautéed kale are often served as side dishes to accompany the sago porridge.[37] In the inland regions, Sago worms are usually served as a type of snack dish.[38][39] Sago worms come from sago trunks which are cut and left to rot. The rotting stems cause the worms to come out. The shape of the sago worms varies, ranging from the smallest to the largest size of an adult's thumb. These sago caterpillars are usually eaten alive or cooked beforehand, such as stir-frying, cooking, frying and then skewered. But over time, the people of Papua used to process these sago caterpillars into sago caterpillar satay. To make satay from this sago caterpillar, the method is no different from making satay in general, namely on skewers with a skewer and grilled over hot coals.[40]

Religion

This province has a large Roman Catholic majority among its native Papuan populace (with a large Protestant minority), in contrast with the neighbouring provinces, where Protestants form a majority and Catholics form significant large minorities among its predominantly Christian populace. But other religions such as Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and Animism/Polytheism are also present in this province, albeit in small pockets.

Religion in South Papua (2022)

See also

References

- Setyaningrum, Puspasari (2022-07-02). "Profil Provinsi Papua Selatan". KOMPAS.com. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2023, Provinsi Papua Selatan Dalam Angka 2023 (Katalog-BPS 1102001.93)

- "Visualisasi Data Kependudukan - Kementerian Dalam Negeri 2022" (visual). www.dukcapil.kemendagri.go.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Aditra, Irsul Panca (2022-04-07). Agriesta, Dheri (ed.). "RUU Pemekaran Provinsi di Papua Disetujui, Ketua Tim PPS Tolak Usulan Nama Provinsi Anim Ha". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- Santoso, Bangun; Ardiansyah, Novian (2022-06-30). "DPR Sahkan RUU DOB, Papua Kini Punya 3 Provinsi Baru: Papua Selatan, Papua Tengah Dan Papua Pegunungan". suara.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- Utama, Felldy (2022-06-30). "Usai RUU DOB Papua Disahkan, Ini Perintah Mendagri Buat Bupati Papua Selatan : Okezone Nasional". Nasional Okezone (in Indonesian). iNews. Jakarta: Okezone. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- Putra, Erik Purnama, ed. (2022-05-10). "Ketua Adat Anim Ha Dukung Pembentukan Provinsi Baru di Papua". Republika Online (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- Jimar, Syarif (2023-02-02). Abaa, Gratianus Silas Anderson (ed.). "Melihat Kota Terpadu Mandiri Salor, Pusat Pemerintahan Provinsi Papua Selatan". Tribun-papua.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Daeli, Onesius Otenieli (2018). "Spiritualitas dan Transformasi". Melintas. Fakultas Filsafat UNPAR. 34 (1): 96–110. doi:10.26593/mel.v34i1.3087.96-110. S2CID 151288950.

- Sinaga, Jaya; Fenetiruma, Raymond; Pelu, Handika (2021). "Pengangkatan Anak Adat dalam Suku Malind di Kabupaten Merauke". Jurnal Restorative Justice (in Indonesian). Fakultas Hukum Universitas Musamus. 5 (1).

- J.P.D.Groen (2022-01-25). "Pengayauan Marind". kombai.nl (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- "Sejarah Boven Digoel" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kabupaten Boven Digoel. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- J.P.D. Groen (2020-12-08). "Belanda Masuk Kali Digul". kombai.nl (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- Utama, Felldy (2022-06-30). "Tak Ada Konflik Merauke Jadi Ibu Kota Provinsi Papua Selatan, Bupati: Sudah Sepakat Dari Awal : Okezone Nasional". Okezone (in Indonesian). iNews. Jakarta: Okezone. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- Manupapami, Fuci (2022-06-30). Hartik, Andi (ed.). "Warga di Merauke Bentangkan Bendera Raksasa Sambut Pengesahan RUU Provinsi Papua Selatan". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Merauke: Kompas Cyber Media. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- "Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri Nomor 137 Tahun 2017 tentang Kode dan Data Wilayah Administrasi Pemerintahan" (in Indonesian). Kementerian Dalam Negeri Republik Indonesia. 29 December 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- "Jati Diri Papua Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Kompas Cyber Media. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Umami, Okta Tri (5 May 2018). "8 Budaya dan Tradisi Papua yang Paling Unik dan Menarik". keluyuran.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Muslim, Abu (October 2019). "The Harmony Taste Of Bakar Batu Tradition On Papua Land". Heritage of Nusantara: International Journal of Religious Literature and Heritage. Balai Litbang Agama Makassar. 8: 100. doi:10.31291/hn.v8i1.545.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Siagian, Wilpret. "Bakar Batu, Tradisi Muslim Papua Sambut Bulan Suci Ramadan". detiknews (in Indonesian). Jayapura: detikcom. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Kobun, Frans L (2020-06-29). "I Papua". Tanah Papua No.1 News Portal. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- Adiningsih, Yulia (2021-06-13). "Tradisi Sasi, Cara Unik Papua Menjaga Laut Panjang Umur". gaya hidup (in Indonesian). Jakarta: CNN Indonesia. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- Syah, Abdel (2018-06-01). "Ritual Sasi Suku Marin Kanume di Merauke". kumparan (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- Kustiani, Rini (16 November 2020). "Mengenal Suku Korowai Papua, Tinggal di Pohon dan Gigi Anjing yang Berharga". Tempo (in Indonesian). Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Susanto, Dalhar; Puti Angelia, Dini; Aditya Giovanni Suhanto, Kevin (1 November 2018). "Rumah Tinggi of Korowai Tribe, Papua: Material and Technology Transformation of Traditional House". E3S Web of Conferences. 67: 04023. Bibcode:2018E3SWC..6704023S. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/20186704023.

- Santoso, Agung Budi. Gultom, Hasiolan Eko Purwanto (ed.). "Papeda, Makanan Sehat Khas Papua". Tribunnews.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Papeda Makanan Khas Maluku dan Papua". Makanan Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Pesta Bakar Batu". Wisata Papua (in Indonesian). 9 November 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Nasrulhak, Akfa (2019-06-03). "Suku Marind Anim Merauke Punya Pizza Khas Lho, Cobain Deh". detikTravel (in Indonesian). Jakarta: detikcom. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "Ikan Bungkus, Pepes Ikan dari Papua yang Harum". MerahPutih. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Riani, Asnida (19 August 2019). "Udang Selingkuh yang Hanya Ada di Papua". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Liputan6.com. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Resep Kue Bagea Ambon". resepkue.net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "Finding Raja Ampat Culinary | Discover Indonesia". goindonesia.blendong.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Ambon yang Selalu Manise". Jalanjalanyuk.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Sagu Lempeng, Rotinya Masyarakat Papua yang Tak Tergantikan". MerahPutih. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Khairunnisa, Syifa Nuri (5 December 2019). Pertiwi F., Ni Luh Made (ed.). "4 Makanan Papua dari Sagu Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Kompas Cyber Media. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Farhan, Afif. "Mengapa Orang Papua Makan Ulat Sagu?". detikTravel (in Indonesian). Jayapura: detikcom. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Alfarizi, Moh Khory (24 December 2019). Prima, Erwin (ed.). "Ulat Sagu Jadi Kuliner Favorit Sejak Masa Prasejarah di Papua". Tempo (in Indonesian). Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Fitria, Riska. "5 Fakta Ulat Sagu, Kuliner Ekstrem yang Kaya Nutrisi". detikfood (in Indonesian). Jakarta: detikcom. Retrieved 4 March 2021.