Hoplitomeryx

Hoplitomeryx is a genus of extinct deer-like ruminants which lived on the former Gargano Island during the Miocene and the Early Pliocene, now a peninsula on the east coast of South Italy. Hoplitomeryx, also known as "prongdeer", had five horns and sabre-like upper canines similar to a modern musk deer.

| Hoplitomeryx Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

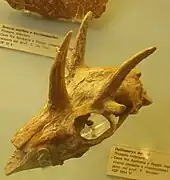

| Cast of the holotype of H. matthei, Naturalis, National Natural History Museum, Leiden, the Netherlands | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | †Hoplitomerycidae |

| Genus: | †Hoplitomeryx Leinders, 1984 |

| Species | |

| |

Its fossilized remains were retrieved from the late 1960s onwards from reworked reddish, massive or crudely stratified silty-sandy clays (terrae rossae), which partially fill the paleo-karstic fissures in the Mesozoic limestone substrate and that are on their turn overlain by Late Pliocene-Early Pleistocene sediments of a subsequently marine, shallow water and terrigenous origin. In this way a buried paleokarst originated.

The fauna from the paleokarst fillings is known as Mikrotia fauna after the endemic murid of the region (initially named "Microtia", with a c, but later corrected, because the genus Microtia was already occupied). Later, after the regression and continentalization of the area, a second karstic cycle started in the late Early Pleistocene, the neokarst, which removed part of the paleokarst fill.

Description

Hoplitomeryx was a deer-like ruminant[1] with a pair of pronged horns above each orbit and one central nasal horn. Hoplitomerycids are not the only horned deer; before the appearance of antlered deer, members of the deer family commonly had horns. Another left-over of this stage is Antilocapra of North America, the only survivor of a once successful group related to Bovidae.

The diagnostic features of Hoplitomeryx are: one central nasal horn and a pair of pronged orbital horns, protruding canines, complete fusion of the navicocuboid with the metatarsal, distally closed metatarsal gully, a non-parallel-sided astragalus,[2] and an elongated patella.[3]

Species

The Hoplitomeryx skeletal material forms a heterogeneous group, containing four size groups from tiny to huge; within the size groups different morphotypes may be present. All size groups share the same typical Hoplitomeryx features. The different size groups are equally distributed over the excavated fissures, and are therefore not to be considered chronotypes. The hypothesis of an archipelago consisting of different islands each with its own morphotype cannot be confirmed so far. The tiny and small specimens show insular dwarfism, but this cannot be said for the medium and huge specimens.

The situation with several co-existing morphotypes on an island is paralleled by Candiacervus (Pleistocene, Crete, Greece). Opinions about its taxonomy differ, and at present two models prevail: one genus for eight morphotypes, or alternatively, two genera for five species. The second model is based upon limb proportions only, but these are invalid taxonomic features for island endemics, as they change under influence of environmental factors that differ from the mainland. Also in Hoplitomeryx the morphotypes differ in limb proportions, but here different ancestors are unlikely, because in that case they all ancestors must have shared the typical hoplitomerycid features. In Candiacervus as well as in Hoplitomeryx, the largest species is as tall as an elk, but gracile and slender.

The large variation is instead explained as an example of adaptive radiation, starting when the Oligocene ancestor colonized the island. The range of empty niches promoted its radiation into several trophic types, yielding a differentiation in Hoplitomeryx. The shared lack of large mammalian predators and the limited amount of food in all niches promoted the development of derived features in all size groups (apomorphies).

Taxonomy

The affinities of Hoplitomeryx have long been contentious, due to its unique morphology not closely resembling any living ruminant group. Originally, they were considered to be relatives of Cervidae (deer). However, analysis of the horn cores show that they more closely resemble those of bovids (bovines, antelopes),[4] an affinitiy also supported by their inner ear anatomy, which resembles those of bovids.[5]

Notes

- (Leinders 1984)

- (Van der Geer 1999)

- (Van der Geer 2004)

- Mazza, Paul Peter Anthony (January 2013). "The systematic position of Hoplitomerycidae (Ruminantia) revisited". Geobios. 46 (1–2): 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.009.

- Mennecart, Bastien; Dziomber, Laura; Aiglstorfer, Manuela; Bibi, Faysal; DeMiguel, Daniel; Fujita, Masaki; Kubo, Mugino O.; Laurens, Flavie; Meng, Jin; Métais, Grégoire; Müller, Bert; Ríos, María; Rössner, Gertrud E.; Sánchez, Israel M.; Schulz, Georg (2022-12-06). "Ruminant inner ear shape records 35 million years of neutral evolution". Nature Communications. 13 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34656-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9726890. PMID 36473836.

References

- De Giuli, C. & Torre, D. 1984a. Species interrelationships and evolution in the Pliocene endemic faunas of Apricena (Gargano Peninsula - Italy). Geobios, Mém. spécial, 8: 379–383.

- De Giuli, C., Masini, F., Torre, D. & Boddi, V. 1986. Endemism and bio-chronological reconstructions: the Gargano case history. Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana,25 (3): 267–276. Modena.

- Dermitzakis, M. & De Vos, J. 1987. Faunal Succession and the Evolution of Mammals in Crete during the Pleistocene. Neues Jahrbuch Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen 173, 3: 377–408.

- De Vos, J. 1979. The endemic Pleistocene deer of Crete. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Series B 82, 1: 59–90.

- De Vos, J. & Van der Geer, A.A.E. 2002. Major patterns and processes in biodiversity: axonomic diversity on islands explained in terms of sympatric speciation. In: Waldren, B. & Ensenyat (eds.). World Islands in Prehistory, International Insular Investigations, V Deia International Conference of Prehistory. Bar International Series, 1095: 395–405.

- Freudenthal, M. 1972: Deinogalerix koenigswaldi nov. gen., nov. spec., a giant insectivore from the Neogene of Italy. Scripta Geologica 14. (includes full text PDF)

- Freudenthal, M. 1976. Rodent stratigraphy of some Miocene fissure fillings in Gargano (prov. Foggia, Italy). Scripta Geologica 37. (includes full text PDF)

- Freudenthal, M. 1985. Cricetidae (Rodentia) from the Neogene of Gargano (Prov. of Foggia, Italy). Scripta Geologica 77. (includes full text PDF)

- Leinders, J.J.M. 1984. Hoplitomerycidae fam. nov. (Ruminantia, Mammalia) from Neogene fissure fillings in Gargano (Italy); part 1: The cranial osteology of Hoplitomeryx gen. nov. and a discussion on the classification of pecoran families. Scripta Geologica 70: 1-51, 9 pl. (includes full text PDF)

- Mazza, P. 1987. Prolagus apricenicus and Prolagus imperialis: two new Ochotonids (Lagomorpha, Mammalia) of the Gargano (Southern Italy). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana, 26 (3): 233–243.

- MAZZA, P. P. A. and RUSTIONI, M. (2011), Five new species of Hoplitomeryx from the Neogene of Abruzzo and Apulia (central and southern Italy) with revision of the genus and of Hoplitomeryx matthei Leinders, 1983. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 163: 1304–1333. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00737.x

- Parra, V., Loreau, M. & Jaeger, J.-J. 1999. Incisor size and community structure in rodents: two tests of the role of competition. Acta Oecologica, 20: 93–101.

- Mazza P.P.A. 2015 Scontrone (central Italy), signs of a 9-million-year-old tragedy. Lethaia, 48: 387–404. doi:10.1111/let.12114

- Mazza, P.P.A., Rossi M.A., Agostini S. (2015) Hoplitomeryx (Late Miocene, Italy), an example of giantism in insular ruminants. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 22: 271–277. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9277-2

- Mazza P. P. A., Rossi M.A., Rustioni M., Agostini S., Masini F. and Savorelli, A. (2016) Observations on the postcranial anatomy of Hoplitomeryx (Mammalia, Ruminantia, Hoplitomericidae) from the Miocene of the Apulia Platform (Italy). Palaeontographica, 307 (1-6): 105–147.

- Van der Geer, A.A.E. 1999. On the astragalus of the Miocene endemic deer Hoplitomeryx from the Gargano (Italy). In: Reumer, J. & De Vos, J. (eds.). Elephants have a snorkel! Papers in honour of P.Y. Sondaar: 325–336. Deinsea 7.

- Van der Geer, A.A.E. 2005. The postcranial of the deer Hoplitomeryx (Mio-Pliocene; Italy): another example of adaptive radiation on Eastern Mediterranean Islands. Monografies de la Societat d'Història Natural de les Balears 12: 325–336.

- Van der Geer, A.A.E. 2005. Island ruminants and the evolution of parallel functional structures. In: Cregut, E. (Ed.): Les ongulés holarctiques du Pliocène et du Pléistocène. Actes Colloque international Avignon, 19-22 septembre. Quaternair, 2005 hors-série 2: 231–240.

- Van der Geer, A.A.E. 2008. The effect of insularity on the Eastern Mediterranean early cervoid Hoplitomeryx: the study of the forelimb. Quaternary International, 182(1)145-159.

- Van der Geer, A., Lyras, G., de Vos, J. & Dermitzakis M. 2010. Evolution of Island Mammals: Adaptation and Extinction of Placental Mammals on Islands. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.