Horse tongue

The horse tongue, like that of most mammals, is pink in color and plays an important role in taste perception. With its long, narrow shape typical of herbivorous animals, it enables the horse to grasp its vegetable food, with the help of its lips and teeth. This tongue is sensitive to pressure and temperature, and is involved in licking and chewing behaviors. Although the mare licks its foal for a long time immediately after birth, there is little research into the gustatory sensitivity of horses and the social use these animals make of their tongues.

.jpg.webp)

The practice of equestrianism by human beings involves potential contact of the horse tongue with a bit, and so precautions must be taken to avoid possible injury to this sensitive, richly vascularized organ. In the event of compression due to unsuitable tacking or handing, the horse tongue turns white or blue, which can ultimately compromise the animal's general health. In equestrian sport, there is a controversial practice of tying up the tongue of racehorses.

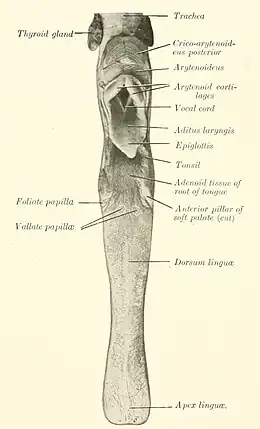

Anatomy

Like all herbivorous mammals, the horse has a narrow, elongated tongue.[1] Psychologist and ethologist Michel-Antoine Leblanc estimates its length at an average of around 40 cm, its width at between 6 and 7 cm, and its weight at an average of 1.2 kg.[2] A horse tongue comprises more than a dozen muscles.[3] It is attached to the rest of the tissues by the frenulum, which enables the horse to chew.[3] The whole is richly vascularized.[4]

The tongue is thick and keratinized.[5] Its medio-dorsal structure, the dorsal lingual cartilage, contains scattered skeletal muscle cells and is rich in white adipose tissue.[5] The epithelium covering the ventral surface of the tongue is thin and keratinized.[5] The lingual muscle nucleus is made up of transverse, longitudinal and perpendicular bundles of skeletal muscle cells.[5]

The Caspian horse, unlike other horse breeds whose tongues have been studied, has no hyaline cartilage.[5]

Taste buds

The horse tongue is covered with taste buds scattered over the entire back surface,[5][6] mainly on the first two-thirds of the tongue.[7] Most of these taste buds have no gustatory function, only mechanical and/or tactile.[6] Taste buds are therefore in the minority.[6] Filiform taste buds are present on the dorsal and lateral parts of the tongue, but not on the ventral part.[8] Their appearance is short and thin, with a general finger-like shape and terminations of variable form.[8] Their very fine keratinized thread protrudes from the surface and is curved backwards.[5]

Fungiform taste buds are scattered among the filiform ones, with a few taste buds, and covered by a keratinized squamous epithelium.[5] Two very large circumvallate taste buds are present on the dorsum of the tongue, near its root.[5] Foliate taste buds are found near the palatoglossus muscle, with a few taste buds papillae.[5]

In 2000, researchers C. J. Pfeiffer, M. Levin and M. A. F. Lopes discovered that the horse tongue is characterized by a highly localized grouping of epidermal cells with an exceptionally high content of PAS-negative trichohyalin cytoplasmic granules at the top of the dermal ridges and under the base of the filiform taste buds.[8] These researchers hypothesized that these granule cells enhance structural strength, in relation to mechanical taste buds.[8]

Comparative anatomy of these taste buds suggests that the fine structure of the tongue in horses shows a more primitive pattern than in goats and cattle: filiform taste buds in horses have a long, thin outer shape, whereas in goats and cattle the outer shape is thick; horses have two large circumvallate taste buds, whereas goats and cattle have 15 or more in the posterior area of the lingual prominence.[9]

Glands

Groups of minor salivary glands are present between the muscle fibers and the lamina propria.[5] Most lingual glands are mucous and most gustatory glands are serous.[5]

Physiology

The mechanical functions of the horse tongue remain moderate, due to its prehensile and neigh functions.[8] The front part of the tongue, in conjunction with the incisors and lips, can grasp vegetable food.[3] In particular, the tongue enables the horse to bring food in grain form to its molars.[10] Horses can also partially clean their teeth with their tongue, dislodging stuck food.[3] The horse's tongue is sensitive to pressure, pain and temperature.[3]

Taste perception

The tongue enables the horse to experience the sense of taste.[3] As with all mammals, its sense of taste also relies on olfaction, enabling it to perceive what Michel-Antoine Leblanc calls "flaveurs".[1]

The horse is reputed to have a highly sensitive sense of taste,[8] although there is little research on this subject.[11] However, it has been established that the presence of taste buds enables the horse to sense the taste of what it touches with its tongue.[11] Like many other mammals, horses are sensitive to bitter, salty, sweet, acidic and umami tastes,[1] and to their concentration, which can trigger gustatory reactions.[11] There is no evidence that sensitivity to acid, bitter, sweet and salty tastes is distributed in specific areas of the tongue.[6] With its tongue, the horse is therefore able to taste various types of food, and spit out those that are not to its liking.[11]

Sensitivity to flavors plays a role in enabling the horse to satisfy its needs.[6] Like other animals, horses are sensitive to sweet taste, and particularly to soluble carbohydrates, which are an energy resource needed by their brains.[6] They are also very sensitive to salty tastes, probably due to their vital need to replenish their sodium reserves.[6] There is evidence that horses may specifically seek out salty foods in case of deficiency.[6] According to Leblanc, horses avoid strong acidity in order to preserve their teeth, and have an aversion to strong bitterness, which enables them to avoid ingesting toxins.[6] There is, however, a very wide range of taste sensitivities among individuals of this species.[6] Ronald Randa and his colleagues have tested foal's sensitivity to four basic flavors, without revealing any general trends in sensitivity and preference among these flavors.[12] Horses generally have a selective plant diet motivated by individual taste preferences.[13] It would also be possible to induce aversions to toxic foods in horses by taste association.[14] Finally, horses that have experienced negative biological effects following ingestion of a particular food could develop a rejection of specific flavors.[1]

Tongue usages

According to ethologists Gerry and Julia Karen Neugebauer, horses use their tongues for licking, chewing, submissive behavior, yawning and drinking.[15] Unlike cattle, they do not generally use their tongues for mutual grooming.[16] During close exploration, horses examine a new object, sniff it, and if the smell pleases them, may touch and taste it using their lips, vibrissae, teeth and tongue.[17]

.jpg.webp)

If a horse sticks its tongue out to the side, this behavior indicates discomfort of varying degrees.[18] With its mouth open, it may roll or stick out its tongue.[19]

Licking

Licking is a normal part of a horse's behavior, whether in the wild or in captivity, with other horses or people.[15] The primary function of licking is to enable the absorption of minerals.[15] To lick, the horse opens its mouth and sticks out its tongue to touch either an object, a fellow horse or a person it knows.[15]

Horses that groom each other can lick each other, for example to absorb water that has settled on the coat.[15] If a horse licks a human being, this behavior may indicate an expectation of food or a lack of mineral salts.[15]

Systematic licking of objects in the horse's immediate environment, such as stable walls, feed troughs or metal bars, is possible before or after feeding; according to the Neugebauers, this behavior may reflect a lack of food or stimulation, and become a behavioral disorder.[20] Systematic licking is in fact the mark of a stereotypy, or stable vice;[21] it differs from normal licking in its repetition and is difficult to eradicate.[22]

In addition to smell, taste may also play a role in the relationship between a foal and its mother, according to Belgian researcher Franck Ödberg.[11] Indeed, the mare licks its foal by giving it a long grooming just after birth, which provides the mare with a gustatory experience of its foal's coat and seems to strengthen the bond between foal and mother.[11] During the breeding season, stallions lick their mares' urine.[15]

Chewing

Chewing is a combination of licking and mastication, during which the mouth is open and the tongue clearly visible, causing the horse to secrete saliva.[21] This behavior can have many reasons and meanings, including submission, relaxation or well-being, but also discomfort.[21] In its natural state, a horse chews when waiting for its turn to drink, when standing up and expressing relaxation after a rest, but also to soothe and show submission to a fellow horse.[21] When relaxed, the horse may chew with light chewing movements.[23] However, the horse may also yawn, chew and shake its head during ambivalent behaviors resulting from behavioral disorders.[24]

This behavior is difficult to interpret in the domestic state, when interacting with humans, due to its wide range of possible meanings, from submission to discomfort to relaxation.[25] Indeed, a horse may chew if its rider approaches it, if it sends contradictory signals, if it feels discomfort linked to its riding equipment,[21] or even after a desired learning experience, with its mouth closed and eyes squinted.[26]

Snapping

.jpg.webp)

Snapping is a submissive signal in which the horse snaps its jaws and shows its tongue, with slight chewing movements.[27] It is often displayed by foals and young horses towards adult horses.[27] The posture taken by the young horse evokes that of suckling its mother, producing suckling noises in rhythm with the clicking of its tongue on the roof of the mouth.[27] This behavior is interpreted by Neugebauer ethologists as self-soothing and a call to play.[28]

This behavior is not normally present in adult horses that have grown up surrounded by their congeners; on the other hand, it can persist and be manifested to human beings by a domestic horse that has not previously learned all the social behaviors of its own species.[28]

Diseases and tics

The horse tongue can be affected by various illnesses, and can be mobilized during tics or stereotypies.

Tics

Certain behaviors involving the tongue have no precise function, and as such are akin to tics or stereotypies, testifying to unsuitable living conditions and a need for care.[26][29] Among these tics is the one where the horse sticks its tongue out of its mouth and twirls it, while wearing a detached facial expression, expressing a lack of stimulation in its environment.[29] There's also a tongue-pulling or hanging tic, with or without a bit in the mouth, which may express a hard hand from the rider.[26][29] These tics can also occur in horses with a bit in the mouth, and generally result in a strong commercial devaluation of the animal.[22] In the case of tics with the bit, their existence does not a priori betray a physical health problem, such as an injury.[22]

In a study of 52 horses subject to tics, five were found to express lip and/or tongue stereotypies.[30]

Diseases affecting the tongue

An infection of a horse tongue by the bacterium Actinobacillus lignieresii, which most commonly affects cattle, was described in 1984.[31]

The tongue can also develop tumors.[32] In exceptional cases, a vascular hamartoma, usually a benign growth, may develop.[33] A case of rhabdomyosarcoma, on the tongue of a five-year-old Quarter Horse mare, was studied in 1993.[34] In 2014, a first case of adenocarcinoma, a malignant tumor that affected a third of the dorsal part of the tongue of an elderly horse, was cited in the scientific literature.[35]

A 5-year-old mare was examined with a soft mass on the dorsal left side of the tongue, then developed numerous similar, coalescing masses along this dorsal left side, all the way to the tip of its tongue. This proliferation of perineal cells remains a matter of conjecture as to its neoplastic nature.[36]

Human intervention on the horse tongue

Grabbing a horse tongue is a well-known method of immobilizing the animal,[3][37] but care must be taken to avoid rough handling.[37]

Some authors suggest stretching the horse tongue to the side, arguing that this helps to desensitize the tongue,[38] while others, on the contrary, recommend never pulling the horse tongue to the side, because of the sensory problems this causes.[39]

The horse tongue is highly sensitive, and therefore vulnerable to injury.[3][40] The main cause of lingual injuries in horses is man-made, and comes from wearing a bit.[3] A horse tongue may also hang over the bit for a variety of reasons, particularly if the rider's hand is too hard or if the bit is not adapted to the horse's mouthpiece, thus preventing the rider from controlling the horse.[41] The horse may then let its tongue hang out to the side.[41] This behavior is to be distinguished from tongue stereotypies, as its origin is not the same.[42] To avoid this problem, there are "snaffle" bits and anti-tongue breakers to be added to the mouthpiece.[43]

Tongue injuries and compressions caused by biting

The main cause of tongue injuries in horses is the use of the bit during riding, whether due to the actions of the rider's hands or to unsuitable equipment.[3] A minority of tongue injuries can result from contact with sharp molars, necessitating intervention by an equine dentist.[44]

When the vascularity of a horse tongue is compromised by its tack, the tongue changes color.[4]

Dr. Jacques Laurent identifies three possible forms of vascularization changes in the horse's tongue:

- arterial compression alone, which gives the tongue a white color ;

- venous compression, which turns the tongue blue and swollen; and

- a mixed form, which is also the most frequent.[4]

Jacques Laurent believes that, over time, compromised vascularization of the horse tongue leads to lingual amyotrophy and impaired epi-critical and deep sensitivity.[4]

Swedish dressage horse rider Patrik Kittel is controversial for repeatedly riding a horse whose tongue has turned blue: Akeem Foldager in 2014[45][46][47] and Watermill Scandic in 2009[47] (a scandal for which he was cleared by the Fédération Équestre Internationale),[48] then again in 2014.[49]

Tongue-tying

In equestrian sport, it's common practice to tie a racehorse's tongue in order to gain better control over the horse,[50][51][52] but also because of the widespread belief that this makes breathing easier.[51][52] The tongue tie is made with a nylon stocking, an elastic band or a piece of leather.[53] First, the horse tongue is grasped to place the tie, which is then fastened around the lower jaw.[53] While some countries, such as Germany, prohibit the practice altogether, Australia allows it in racing.[53] Around 20 % of Australian racehorses are affected.[53]

Tongue-tying causes injury to horses: more than half of users report a change in the color of the horse's tongue, 8.6 % have seen cuts on the tongue, and 2.9 % report that the horse's nerves have been irreparably damaged.[52] There is no evidence that tying up the tongue of a racehorse with no health problems can make breathing easier, either at rest or under racing conditions.[51][54][55]

A benefit is proven only in animals suffering from respiratory obstructions, such as dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP).[51][54] Tongue attachment leads to a reduction in the depth of the thyroid cartilage and basihyoid bone, compared with the unharnessed position, demonstrating a significant effect on the positions of the basihyoid and thyroid cartilage in the horse, and thus with an effect on the structure of the upper respiratory tract.[50] However, there is no evidence that tongue attachment can alter upper respiratory tract mechanics after sternothyrohyoid myectomy (cutting of certain muscles) in clinically normal horses.[56]

A statistical analysis of racehorses in the UK suggests that racehorses with tongue-ties perform better than those without.[57]

See also

References

- Leblanc (2019, p. 121)

- Leblanc (2019, p. 121-122)

- Clark, Aimi (2016). "14 facts you need to know about your horse's tongue". Horse & Hound. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Laurent, Jacques (2014). "Comment se constitue le phénomène de la « langue bleue ?". Cheval Savoir (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Rezaian, M. (2006). "Absence of Hyaline Cartilage in the Tongue of 'Caspian Miniature Horse'". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 35 (4): 241–246. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0264.2005.00673.x. ISSN 1439-0264. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Leblanc (2019, p. 122)

- Fraser (2010, p. 23)

- Pfeiffer, Levin & Lopes (2000, p. 37)

- Kobayashi, K.; Jackowiak, H.; Frackowiak, H.; Yoshimura, K. (2005). "Comparative morphological study on the tongue and lingual papillae of horses (Perissodactyla) and selected ruminantia (Artiodactyla)". Italian journal of anatomy and embryology = Archivio italiano di anatomia ed embriologia. 110 (2): 55–63. ISSN 2038-5129. PMID 16101021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Fraser (2010, p. 48)

- Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 86)

- Leblanc (2019, p. 123)

- Leblanc (2019, p. 124)

- Leblanc (2019, p. 125)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 202)

- Fraser (2010, p. 3)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 133)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 135)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 188)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 202-203)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 203)

- Fraser (2010, p. 197)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 117)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 88-89)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 203-204)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 204)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 256)

- Neugebauer & Neugebauer (2012, p. 257)

- Zeitler-Feicht (2003, p. 141)

- Mills, D. S.; Levine, Emily; Landsberg, Gary (2005). Current Issues and Research in Veterinary Behavioral Medicine: Papers Presented at the Fifth Veterinary Behavior Meeting. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-409-5.

- Baum, K. H.; Shin, S. J.; Rebhun, W. C.; Patten, V. H. (1984). "Isolation of Actinobacillus lignieresii from enlarged tongue of a horse". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 185 (7): 792–793. ISSN 1943-569X. PMID 6490508. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Schneider, A.; Tessier, C.; Gorgas, D.; Kircher, P. (2010). "Magnetic resonance imaging features of a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumour with 'ancient' changes in the tongue of a horse". Equine Veterinary Education. 22 (7): 346–351. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3292.2010.00088.x. ISSN 2042-3292. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Brunson, Brandon L.; Taintor, Jennifer; Newton, Joseph; Schumacher, John (2006). "Vascular hamartoma in the tongue of a horse". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 26 (6): 275–277. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2006.04.010. ISSN 0737-0806. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Hanson, P. D; Frisbie, D. D.; Dubielzig, R. R.; Markel, M. D. (1993). "Rhabdomyosarcoma of the tongue in a horse". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 202 (8): 1281–1284. ISSN 1943-569X. PMID 8496087. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Laus, Fulvio; Rossi, Giacomo; Paggi, Emanuele; Bordicchia, Matteo (2014). "Adenocarcinoma Involving the Tongue and the Epiglottis in a Horse". Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 76 (3): 467–470. doi:10.1292/jvms.13-0417. PMC 4013378. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Vashisht, K.; Rock, R. W.; Summers, B. A. (2007). "Multiple Masses in a Horse's Tongue Resulting from an Atypical Perineurial Cell Proliferative Disorder". Veterinary Pathology. 44 (3): 398–402. doi:10.1354/vp.44-3-398. ISSN 0300-9858. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Fraser (2010, p. 186)

- Boudard, Jean-Michel (2020). Le stretching pour votre cheval (in French). Vog Vigot Maloine. p. 115. ISBN 978-2-7114-5194-4.

- Honnay, Melissa (2015). Apprendre le cheval pour mieux le comprendre (in French). Editions Edilivre. ISBN 978-2-332-86389-8.

- Kitchener, Nicole (2019). "Everything You Need to Know About the Equine Tongue". Horse Canada. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Zeitler-Feicht (2003, p. 187)

- Zeitler-Feicht (2003, p. 142)

- Ancelet, Catherine (2006). Les fondamentaux de l'équitation : galops 1 à 4 : programme officiel (in French). Paris: Amphora. p. 336. ISBN 2-85180-707-2. OCLC 421687899.

- Fraser (2010, p. 226)

- Tsaag Valren, Amélie; Bataille, Lætitia. "Maltraitance : la langue bleue d'Akeem Foldager". Cheval Savoir (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Heath, Sophia (2015). "Andreas Helgstrand guilty of 'improper use of bit and bridle'". Horse & Hound. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Heath, Sophia (2014). "'Blue tongue' leads to social media outrage". Horse & Hound. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "Patrick Kittel escapes disciplinary action by FEI over 'blue tongue'". Horse & Hound. 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Tsaag Valren, Amélie (2014). "Aux JEM : une nouvelle affaire de langue bleue". Cheval Savoir (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Chalmers, H. J.; Farberman, A.; Bermingham, A.; Sears, W. (2013). "The use of a tongue tie alters laryngohyoid position in the standing horse". Equine Veterinary Journal. 45 (6): 711–714. doi:10.1111/evj.12056. ISSN 2042-3306. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Franklin, S. H.; Naylor, J. R. J.; Lane, J. G. "The effect of a tongue-tie in horses with dorsal displacement of the soft palate". Equine Veterinary Journal. 34 (34): 430–433. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.2002.tb05461.x. ISSN 2042-3306. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Weller et al. (2021, p. 622)

- McGreevy, Paul; Franklin, Samantha (2018). "Over 20% of Australian horses race with their tongues tied to their lower jaw". The Conversation. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Cornelisse, Cornelis J.; HolcombeS, Susan J.; Derksen, Frederik J.; Berney, Cathy (2001). "Effect of a tongue-tie on upper airway mechanics in horses during exercise". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 62 (5): 775–778. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.775. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Cornelisse, Cornelis J.; Rosenstein, Diana S.; Derksen, Frederik J.; Holcombe, Susan J. (2001). "Computed tomographic study of the effect of a tongue-tie on hyoid apparatus position and nasopharyngeal dimensions in anesthetized horses". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 62 (12): 1865–1869. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1865. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Beard, Warren L.; Holcombe, Susan J.; Hinchcliff, Kenneth W. (2001). "Effect of a tongue-tie on upper airway mechanics during exercise following sternothyrohyoid myectomy in clinically normal horses". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 62 (5): 779–782. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.779. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Barakzai, S. Z.; Finnegan, C.; Boden, L. A. (2009). "Effect of 'tongue tie' use on racing performance of Thoroughbreds in the United Kingdom". Equine Veterinary Journal. 41 (8): 812–816. doi:10.2746/042516409X434134. ISSN 2042-3306. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

Bibliography

- Fraser, Andrew Ferguson (2010). The Behaviour and Welfare of the Horse. CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-629-7.

- Leblanc, Michel-Antoine (2019). Comment pensent les chevaux ? (in French). Éditions Vigot-Maloine. ISBN 978-2-7114-2568-6.

- Leblanc, Michel-Antoine; Bouissou, Marie-France (2021). Cheval, qui es-tu ? (in French). Paris: Vigot frères. ISBN 978-2-7114-2625-6.

- Neugebauer, Gerry M.; Neugebauer, Julia Karen (2012). Le comportement du cheval (in French). Delachaux et Niestlé. ISBN 978-2-603-01847-7.

- Zeitler-Feicht, Margit (2003). Horse Behaviour Explained: Origins, Treatment and Prevention of Problems. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-2113-8.

- Gargiulo, A. M.; Pedini, V.; Ceccarelli, P.; Lorvik, S. (1995). A lectin histochemical study of gustatory (von Ebner's) glands of the horse tongue. Vol. 24. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0264.1995.tb00022.x. ISSN 0340-2096. PMID 8588703. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Pfeiffer, C. J.; Levin, M.; Lopes, M. a. F. (2000). Ultrastructure of the Horse Tongue: Further Observations on the Lingual Integumentary Architecture. Vol. 29. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2000.00232.x. ISSN 1439-0264. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Weller, Dominic; Franklin, Samantha; White, Peter; Shea, Glenn (2021). The Reported Use of Tongue-Ties and Nosebands in Thoroughbred and Standardbred Horse Racing—A Pilot Study. Vol. 11. Animals. doi:10.3390/ani11030622. Retrieved 29 October 2021.