Horseshoe Curve (Pennsylvania)

The Horseshoe Curve is a three-track railroad curve on Norfolk Southern Railway's Pittsburgh Line in Blair County, Pennsylvania. The curve is roughly 2,375 feet (700 m) long and 1,300 feet (400 m) in diameter. Completed in 1854 by the Pennsylvania Railroad as a way to reduce the westbound grade to the summit of the Allegheny Mountains, it replaced the time-consuming Allegheny Portage Railroad, which was the only other route across the mountains for large vehicles. The curve was later owned and used by three Pennsylvania Railroad successors: Penn Central, Conrail, and Norfolk Southern.

Horseshoe Curve | |

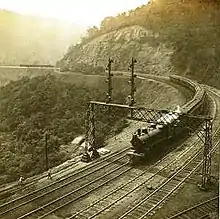

A March 2006 aerial photo of Horseshoe Curve. Trains headed counterclockwise around the curve are ascending. The visitor center and observation park are at the apex of the curve, and a reservoir is in the valley extending from it. | |

| |

| Location | Logan Township, Blair County, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Altoona, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°29′51.5″N 78°29′3″W |

| Built | 1851–1854 |

| Built by | Pennsylvania Railroad |

| Architect | John Edgar Thomson |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000647[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | November 13, 1966 |

Horseshoe Curve has long been a tourist attraction. A trackside observation park was completed in 1879. The park was renovated and a visitor center built in the early 1990s. The Railroaders Memorial Museum in Altoona manages the center, which has exhibits pertaining to the curve. The Horseshoe Curve was added to the National Register of Historic Places and designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It became a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 2004.

Location and design

Horseshoe Curve is 5 miles (8 km) west of Altoona, in Logan Township, Blair County. It sits at railroad milepost 242 on the Pittsburgh Line, which is the Norfolk Southern Railway Pittsburgh Division main line between Pittsburgh and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Horseshoe Curve bends around a dam and lake, the highest of three Altoona Water Authority reservoirs that supply water from the valley to the city.[2] It spans two ravines formed by creeks: Kittanning Run, on the north side of the valley, and Glenwhite Run, on the south.[3][4] The Blair County Veterans Memorial Highway (SR 4008) follows the valley west from Altoona and tunnels under the curve.[5]

Westbound trains climb a maximum grade of 1.85 percent for 12 miles (19 km) from Altoona to Gallitzin.[6] Just west of the Gallitzin Tunnels, trains pass the summit of the Allegheny Mountains, then descend for 25 miles (40 km) to Johnstown on a grade of 1.1 percent or less.[6] The overall grade of the curve was listed by the Pennsylvania Railroad as 1.45 percent; it is listed as 1.34 percent by Norfolk Southern.[3][7] The curve is 2,375 feet (724 m) long and, at its widest, about 1,300 feet (400 m) across.[8][9] For every 100 feet (30 m), the tracks at the Horseshoe Curve bend 9 degrees 15 minutes, with the entire curve totaling 220 degrees.[10][8]

The rise of a westbound train through the curve can be described in several ways. One measurement is from the point where the rails north of the curve start to bow out to a point on the line directly south, across the original Kittanning Reservoir: across this north–south distance of 1,119 feet (340 m), a train rises from 1,601 feet (490 m) above sea level to 1,660 feet (510 m). Another measurement is from the point at which the rails coming west out of Altoona make their first detour north to the curve, to a point across Lake Altoona where the rails are on their one mile straight run south before turning westward to the Gallitzin Tunnels; this measurement encompasses the entire Curve structure, including both reservoirs built in its bounds to protect the curve from flooding: across this north–south distance of 1,006 feet (310 m), a westbound train rises from 1,473 feet (450 m) to 1,706 feet (520 m).[11] This latter rise—133 vertical feet in 1,006 linear feet—is a 13.2% grade, completely unascendable by conventional railroads, which usually stick to grades of 2.2% or less.[12]

Each track consists of 136 pounds per yard (67.5 kg/m), welded rail.[7] Before dieselization and the introduction of dynamic braking and rail oilers, the rails along the curve were transposed—left to right and vice versa—to equalize the wear on each rail from the flanges of passing steam locomotives and rail cars, thereby extending their life.[13]

History

_cph_3b39962_http-_hdl.loc.gov_loc.pnp_cph.3b39962.jpg.webp)

Origin

In 1834 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania built the Allegheny Portage Railroad across the Allegheny Mountains to connect Philadelphia and Pittsburgh,[10] as part of the Main Line of Public Works. The Portage Railroad was a series of canals and inclined planes and remained in use until the mid-19th century. The Pennsylvania Railroad was incorporated in 1847 to build a railroad from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, replacing the cumbersome Portage Railroad.[10]

Using surveys completed in 1842,[14] the state's engineers recommended an 84-mile (135 km) route west from Lewistown that followed the ridges with a maximum grade of 0.852 percent.[15] But the Chief Engineer for the Pennsylvania Railroad, John Edgar Thomson, chose a route on lower, flatter terrain along the Juniata River and accepted a steeper grade west of Altoona. The valley west of Altoona was split into two ravines by a mountain; surveys had already found a route with an acceptable grade east from Gallitzin to the south side of the valley, and the proposed Horseshoe Curve would allow the same grade to continue to Altoona.

Construction

Work on Horseshoe Curve began in 1850.[9] It was done without heavy equipment, only men "with picks and shovels, horses and drags".[10] Engineers built an earth fill over the first ravine encountered while ascending, formed by Kittanning Run, cut the point of the mountain between the ravines, and filled in the second ravine, formed by Glenwhite Run.[9] The 31.1-mile (50.1 km) line between Altoona and Johnstown, including Horseshoe Curve, opened on February 15, 1854. The total cost was $2,495,000 or $80,225 per mile ($49,850 /km).[13]

In 1879, the remaining part of the mountain inside the curve was leveled to allow the construction of a park and observation area—the first built for viewing trains.[16] As demand for train travel increased, a third track was added to the curve in 1898 and a fourth was added two years later.[13][17]

From around the 1860s to just before World War II passengers could ride to the PRR's Kittanning Point station near the curve.[18][19] Two branch railroads connected to the main line at Horseshoe Curve in the early 20th century; the Kittanning Run Railroad and the railroad owned by the Glen White Coal and Lumber Company followed their respective creeks to nearby coal mines.[20] The Pennsylvania Railroad delivered empty hopper cars to the Kittanning Point station which the two railroads returned loaded with coal.[20] In the early 1900s, locomotives could take on fuel and water at a coal trestle on a spur track across from the station.[21]

A reservoir was built at the apex of the Horseshoe Curve in 1887 for the city of Altoona; a second reservoir, below the first, was finished in 1896.[22] The third reservoir, Lake Altoona, was completed by 1913.[23] A macadam road to the curve was opened in 1932 allowing access for visitors, and a gift shop was built in 1940.[18]

Horseshoe Curve was depicted in brochures, calendars and other promotional material; Pennsylvania Railroad stock certificates were printed with a vignette of it.[24] The Pennsylvania pitted the scenery of Horseshoe Curve against rival New York Central Railroad's "Water Level Route" during the 1890s.[18] A raised-relief, scale model of the curve was included as part of the Pennsylvania Railroad's exhibit at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[25] Pennsylvania Railroad conductors were told to announce the Horseshoe Curve to daytime passengers—a tradition that continues aboard Amtrak trains.[17]

World War II and post-war

During World War II, the PRR carried troops and materiel for the Allied war effort, and the curve was under armed guard.[26] The military intelligence arm of Nazi Germany, the Abwehr, plotted to sabotage important industrial assets in the United States in a project code-named Operation Pastorius.[27] In June 1942, four men were brought by submarine and landed on Long Island, planning to destroy such sites as the curve, Hell Gate Bridge, Alcoa aluminum factories and locks on the Ohio River.[28] The would-be saboteurs were quickly apprehended by the Federal Bureau of Investigation after one, George John Dasch, turned himself in. All but Dasch and one other would-be saboteur were executed as spies and saboteurs.[29]

Train count peaked in the 1940s with over 50 passenger trains per day, along with many freight and military trains.[26] Demand for train travel dropped greatly after World War II, as highway and air travel became popular.[30]

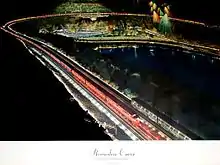

During the 1954 celebration of the centennial of the opening of Horseshoe Curve, a night photo was arranged by Sylvania Electric Products using 6,000 flashbulbs and 31 miles (50 km) of wiring to illuminate the area.[31] The event also commemorated the 75th anniversary of the incandescent light bulb. Pennsylvania steam locomotive 1361 was placed at the park inside the Horseshoe Curve on June 8, 1957.[32] It is one of 425 K4s-class engines: the principal passenger locomotives on the Pennsylvania Railroad that regularly plied the curve.[33] The Horseshoe Curve was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was designated a National Historic Landmark on November 13, 1966.[1][34] The operation of the observation park was transferred to the city of Altoona the same year.[35] The Pennsylvania Railroad was combined with the New York Central Railroad in 1968. The merger created Penn Central, which went bankrupt in 1970 and was taken over by the federal government in 1976, as part of the merger that created Conrail. The second track from the inside at the Horseshoe Curve[36] was removed by Conrail in 1981.[37] The K4s 1361 was removed from the curve for a restoration to working order in September 1985 and was replaced with the ex-Conrail EMD GP9 diesel-electric locomotive 7048 that was repainted into a Pennsylvania Railroad scheme.[18]

Starting in June 1990, the park at the Horseshoe Curve underwent a $5.8 million renovation funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation and by the National Park Service through its "America's Industrial Heritage Project".[38] The renovations were completed in April 1992 with the dedication of a new visitor center.[38] In 1999, Conrail was divided between CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern, with the Horseshoe Curve being acquired by the latter. The Horseshoe Curve was lit up again with fireworks and rail-borne searchlights during its sesquicentennial in 2004 in homage to the 1954 celebrations.[39][40] It was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2004.[41]

Current operations

The curve remains busy as part of Norfolk Southern's Pittsburgh Line: as of 2008, it was passed by 51 scheduled freight trains each day, not including locals and helper engines, which can double the number.[42] Coupled to the rear of long trains, helper engines add power going up and help to brake coming down. For some years before 2020, Norfolk Southern used SD40Es as helpers; since then, 4,300-horsepower (3,200 kW) EMD SD70ACU locomotives are used.[43][44][45] In 2012, Norfolk Southern said annual traffic passing Horseshoe Curve was 111.8 million short tons (101.4 Mt), including locomotives.[7] Amtrak's Pennsylvanian between Pittsburgh and New York City rounds the curve once each way daily. Maximum speeds for trains at Horseshoe Curve are 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) for freight and about 35 miles per hour (56 km/h) for passenger trains. [46]

Trackside attractions

The Railroaders Memorial Museum in Altoona manages a visitor center next to the curve.[47] The 6,800-square-foot (632 m2) center has historical artifacts and memorabilia relating to the curve and a raised-relief map of the Altoona–Johnstown area.[38] Access to the curve is by a 288-foot (88 m) funicular or a 194-step stairway.[18][47] The funicular is single-tracked, with the cars passing each other halfway up the slope; the cars are painted to resemble Pennsylvania Railroad passenger cars.[38] A former "watchman's shanty" is in the park.[48] Horseshoe Curve is popular with railfans; watchers can sometimes see three trains passing at once.[47][49] In August 2012, the former Nickel Plate Road (NKP) steam locomotive No. 765 traversed Horseshoe Curve: the first steam locomotive to do so since 1977, while deadheading to and from Harrisburg as part of Norfolk Southern's 21st Century Steam program.[50] NKP 765 returned to the curve in May 2013 with public excursion trains from Lewistown to Gallitzin.[51]

See also

Notes

- "Horsheshoe Curve". NPSGallery. National Park Service. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- Seidel 2008, p. 18.

- Hollidaysburg Quadrangle (Map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute. United States Geological Survey. 2013.

- Altoona Quadrangle (Map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute. United States Geological Survey. 2013.

- Act of Dec. 4, 1992, P.L. 775, No. 120.

- Borkowski 2008, p. 112.

- Engineering Design and Construction (2012). Pittsburgh Division (PDF). Track Charts. Atlanta, Georgia: Norfolk Southern Railway. p. 026. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Greenwood 1975, sec. 7, p. 1.

- Greenwood 1975, sec. 8, p. 2.

- Howe, Ward Allan (February 14, 1954). "A Century-Old Wonder of Railroading". The New York Times. p. X25.

- "Horseshoe Curve Region". Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- "Grades and Curves". Trains. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- Greenwood 1975, sec. 8, p. 3.

- Brown 2015, p. 43.

- Greenwood 1975, sec. 8, p. 1.

- "Marvel of engineering celebrating milestone". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. June 30, 2004. p. B10.

- Woods, Claire (Spring 2010). "Up and Down 'Round and 'Round and Back Again". Literary Map of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Center of the Book, Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- Cupper, Dan (August 2004). "Horseshoe Fascination". Trains. Kalmbach. 64 (8): 53.

- Seidel 2008, pp. 18–19.

- United States, 63rd Congress (1915). Transportation of Coal: Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Naval Affairs United States Senate. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 367.

- Seidel 2008, pp. 19, 25.

- Knight, Charles W (September 21, 1899). "Flood Water Channel of the Reservoirs of Altoona, Pa". Engineering News and American Railway News. XLII (12): 200.

- "Altoona Has Solved Its Water Problems". Municipal Journal. XXXV (23): 771. December 4, 1913.

- Seidel 2008, p. 43.

- Ely, Theo N; Watkins, J. Elfreth (1893). Catalogue of the exhibit of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company at the World's Columbian Exposition. Chicago: Pennsylvania Railroad. p. 13.

- Seidel 2008, p. 113.

- Cohen 2002, p. 47.

- Cohen 2002, pp. 46–47.

- Cohen 2002, p. 53.

- Michelmore, David L (February 19, 1991). "Railroaders remember glory days, downside". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 7.

- "Horseshoe Centenary". Life. Henry Luce. November 1, 1954. p. 37.

- Staufer & Pennypacker 1962, p. 161.

- Staufer & Pennypacker 1962, p. 159.

- "List of National Historic Landmarks by State" (PDF). National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service. October 2014. p. 83. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- "Horseshoe Curve Park is Approved". The Daily News. Huntingdon and Mount Union, Pennsylvania. May 28, 1957. p. 3.

- For a description and photos of the curve when it still had four tracks, see "Rail Guide to the Horseshoe Curve." (1976, PC Publications).

- "Half century of change". Trains. Kalmbach. 64 (8): 56. August 2004.

- "Renovated Horseshoe Curve museum expecting many tourists this year". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. March 1, 1992. p. F5. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- "Horseshoe Curve's 150th: Fireworks and Flashbulbs". Trains. Kalmbach. 64 (6): 14. June 2004.

- "Horseshoe Curve's bright birthday party". Trains. Kalmbach. 64 (10): 16. October 2004.

- "Horseshoe Curve Designated a Civil Engineering Landmark". ASCE News. American Society of Civil Engineers. 29 (4): 10. April 2004.

- Borkowski 2008, p. 109.

- Borkowski 2008, pp. 112–113.

- Seidel 2008, pp. 31, 108.

- "With a proud legacy, Juniata plays a key role in NS' future" (PDF). BizNS. Norfolk Southern Railway. 3 (6): 5. November–December 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- Pittsburgh Division Timetable (2012 ed.). Norfolk Southern Corp. 2012.

- Wrinn, Jim, ed. (2009). Tourist Trains Guidebook (2nd ed.). Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach. p. 199.

- Treese, Lorett (2003). Railroads of Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 203. ISBN 0-8117-2622-3.

- Barry, Dan (November 3, 2009). "Awesome Train Set, Mr. Buffett". The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- Kibler, William (August 18, 2012). "Steam engine passes through Altoona". Altoona Mirror. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- Kibler, William (March 4, 2013). "Locomotive set for more visits". Altoona Mirror. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

References

- Borkowski, Richard C. Jr. (2008). Norfolk Southern Railway. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3249-8.

- Brown, Jeff L. (January 2015). "Around the Bend: Horseshoe Curve". Civil Engineering. American Society of Civil Engineers: 42–45. ISSN 0885-7024. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- Cohen, Gary (February 2002). "The Keystone Kommandos". The Atlantic Monthly. 289 (2): 46–59. ISSN 1072-7825.

- Greenwood, Richard (August 9, 1975). "Horseshoe Curve" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places—Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- Seidel, David W. (2008). Horseshoe Curve. Images of Rail. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5707-6.

- Staufer, Alvin F.; Pennypacker, Bert (1962). Pennsy Power: Steam and Electric Locomotives of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1900-1957. Research by Martin Flattley. Carollton, Ohio: Alvin F. Staufer. ISBN 978-0-9445-1304-0.