House of Priests

The building that is referred to as the Priests' House, or House of Priests, at Dura-Europos near the village of Salhiyah in eastern present-day Syria, is one of three buildings that was excavated in block H2. It is hypothesized to be the home of priests from the Temple of Atargatis based on its proximity to the two neighboring temples and graffiti found in the third Excavation season.[1]

Discovery

The House of Priests was excavated between 1929 and 1930 under French archeologist and Egyptologist Maurice Pillet, who was then Field Director of the excavation at Dura-Europos on the Syrian Euphrates, during the third expedition to the site.[2] Pillet's two assistants, André Naudy and Henry T. Rowell, took over the direction of the campaign after he fell ill and left the site in January 1930.[3] The excavations of block H2 were disturbed by heavy rains in January and February 1930, especially since the temples and the house were on a low level which left them susceptible to flooding. To remedy this, the team built an embankment southwest of the block to prevent flooding and subsequently rebuilt it three times.[4]

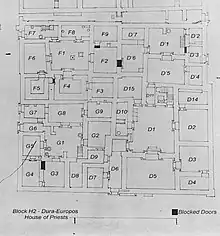

The house is located on the southeastern corner of block H2, which it shares with the Temple of Atargatis and the Temple of Artemis. This closeness to the two temples along with evidence of a joint upper level lead to its classification as a place of residence for the priests of the Temple of Atargatis.[1]

Architectural structure

The house is 440.5 m2 and has a total of 15 rooms with one entrance at H2-D6. There is no evidence of when the house was constructed.[5]

At the time of discovery the four courtyards, H2-D1, H2-G1, H2-F1, and H2-D'5, provided reason to believe that the unit contained four homes, but upon further excavation, all of the houses had connecting doorways except for H2-F, which was formerly connected but was later blocked off and separated.[6] These connections, along with two separate external doors in the larger home, imply that the residents were able to convene without having to exit the home, which implies that they had relationships between households.[6]

Among the other evidence that is referenced when referring to this building as the House of Priests is the character of the building. It is large, including two stories, multiple courtyards, and a fresco that was believed to depict a funerary scene. Also, there was formerly a door connecting the house to the Temple of Atargatis that had been barricaded, and walls that are thought to have supported a passage on an upper floor.[1] The small walls between the temple and the house have also been speculated to have constructed to keep out animals, though this would be an unlikely function in a place so sacred and small.[7] The passage between the temple and the house is believed to have been constructed after an earthquake in A.D. 160, replacing some of the footprint of the house.[8] While the doors that border the external streets are on the same level, the passages within the block are 0.70 m. to 1 m. above the levels of the floors and the street.[7]

The graffiti discovered in the vestibule of the house includes animals, people, and architectural forms such as the city gate and walls.[1] Also, a fresco stele on the southeast wall of room H2-O was discovered in somewhat poor condition but is believed to depict a funerary repast scene.[1] The relief is 0.55 m. x 0.40 m. and is 0.60 m. above the floor. The stele depicts three figures, one lying on a bed, one presenting an offering, and one more barely decipherable figure as well as a possible thymiateria.[1] This imagery is seen throughout Dura-Europos and Graeco-Roman antiquity, most notably in the temple of the Palmyrene gods.[9]

The house is ornate, and similar in size to those of wealthy families, yet no precious art was found in it, further alluding to its function as a dwelling of notable, but not aristocratic, people. At the time of discovery, only one external door of the House was found, which signifies that the residents were of a class that is intentionally separated from the exterior world.[6] Also, there was an oven and a kneading trough discovered in room H2-D10, implying the existence of a bakery room within the building.[1] H2-G7 has a door from a somewhat isolated room to the street, as does H2-G6 right next to it, which poses the possibility of a shop that is connected to the house.[10]

Findings

Among the finds at the House of Priests was one of four versions of a painted plaster relief depicting the Greek goddess Aphrodite in a niche. The relief, dated from 113 B.C.–A.D. 256 and measuring 11 7/8 in. × 12 in. × 3 1/4 in., depicts the goddess standing nude under an arch and was found in two fragments, split horizontally into two halves.[11] She holds a mirror in her left hand and fixes her hair with her right, similar in form to Praxiteles' Aphrodite of Arles.[12] Other similar reliefs were found, one with nearly the same dimensions and depicting the same figure and scene, one fragment of the bottom portion of the relief with similar dimensions, and one inconclusive relief that has since been lost but maintains the clearest outline of the figure's right hip.[13] The primary evidence that these reliefs were made from the same mold is that they all depict details of the anklets around the figure's legs and the columns framing the figure.[13] Additionally, the mold was likely worn down, as all figures are somewhat indistinct.[13]

One of the other versions of this relief was found in block G5-C2 in a building that was believed to be a brothel.[14] The significance of this relief is contested, as Greek religion was not thought to be surviving at Dura-Europos, evidenced by a lack of architecturally Greek temples.[15] However, Aphrodite and Hercules were the two most depicted Greco-Roman deities and Aphrodite is hypothesized to have been worshipped domestically.[16] Further, figural nudity was rarely depicted in Parthian art and the voluptuousness of the figure alludes to Greek influence, so the relief has been classified as a depiction of Aphrodite.[17]

Thirty nine lamps were found in room O of the house as well as a stele measuring 0.55 m. x 0.40m.

Evidence of local production was found in the House. A steatite mould with a similar lead patera were discovered, implying that mould was used in production.[18]

References

- Baur, P. V. C. (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 25–39.

- McFadyen, Lesley; Hicks, Dan. Archaeology and Photography: Time, Objectivity and Archive (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000213287.

- Baur, P. V. C. (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. pp. xiiv.

- Baur, P. V. C (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. p. 3.

- Baur, P. V. C. (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. p. 34.

- Baird, Jennifer A. (2014). The inner lives of ancient houses : an archaeology of Dura-Europos (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-19-968765-7. OCLC 873746891.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Baur, P. V. C. (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. p. 27.

- Downey, Susan B. (1977). The stone and plaster sculpture. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California. p. 164. ISBN 0-917956-04-4. OCLC 4389924.

- Baur, P. V. C. (1932). The Excavations at Dura-Europos (Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work November 1929-March 1930 ed.). Yale University Press. p. 26.

- Baird, Jennifer A. (2014). The inner lives of ancient houses : an archaeology of Dura-Europos (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-968765-7. OCLC 873746891.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Relief of Aphrodite in a niche". artgallery.yale.edu. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- Downey, Susan B. (1977). The stone and plaster sculpture. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California. p. 166. ISBN 0-917956-04-4. OCLC 4389924.

- Downey, Susan B. (1977). The stone and plaster sculpture. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California. pp. 41–2. ISBN 0-917956-04-4. OCLC 4389924.

- Baird, Jennifer A. (2014). The inner lives of ancient houses : an archaeology of Dura-Europos (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-19-968765-7. OCLC 873746891.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rostovtzeff, Michael (1938). Dura-Europos and its Art. Oxford University. p. 61.

- Downey, Susan B. (1977). The stone and plaster sculpture. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California. p. 164. ISBN 0-917956-04-4. OCLC 4389924.

- Downey, Susan B. (1977). The stone and plaster sculpture. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California. pp. 153–4. ISBN 0-917956-04-4. OCLC 4389924.

- Baird, Jennifer A. (2014). The inner lives of ancient houses : an archaeology of Dura-Europos (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. pp. 185–6. ISBN 978-0-19-968765-7. OCLC 873746891.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)