How to Be Both

How to Be Both is a 2014 novel by Scottish author Ali Smith, first published by Hamish Hamilton.[1] It was shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize[2] and the 2015 Folio Prize.[3] It won the 2014 Goldsmiths Prize,[4][5] the Novel Award in the 2014 Costa Book Awards and the 2015 Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction.[6]

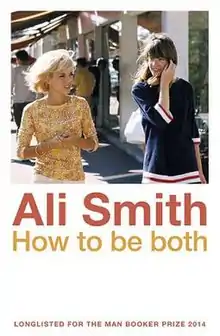

First Edition cover, featuring photograph of Sylvie Vartan and Françoise Hardy by Jean-Marie Périer. The photograph is mentioned in the novel, George being likened to the image of Sylvie Vartan. | |

| Author | Ali Smith |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Hamish Hamilton |

Publication date | August 2014 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 372 |

| ISBN | 978-0375424106 |

| Preceded by | Artful |

| Followed by | Autumn |

Plot introduction

The story is told from two perspectives: those of George, a pedantic 16-year-old girl living in contemporary Cambridge, and Francesco del Cossa, an Italian renaissance artist responsible for painting a series of frescoes in the 'Hall of the Months' at the Palazzo Schifanoia (translated as the 'Palace of Not Being Bored' in the novel) in Ferrara, Italy. Two versions of the book were published simultaneously, one in which George's story appears first, the other in which Francesco's comes first.[7]

George

Struggling to come to terms with the sudden death of her mother (Dr Carol Martineau Economist Journalist Internet Guerilla Interventionist – according to her obituary), George attends counselling sessions at her school. She also has to look after her younger brother, Henry, and cope with her alcoholic father. She recalls travelling with her mother to see the frescos in Ferrara and asking her about the elusive painter Francesco del Cossa. Her mother believed herself to be being monitored by the security services as a result of her subversive activities and George has inherited this belief, and becomes obsessed with Lisa Goliard a friend of her mother's with a suspicious claim to being an artist. George also becomes obsessed with Francesco and travels frequently to London to view his portrait of St. Vincent Ferrer.

Francesco

Francesco finds his disembodied self in front of his portrait of St. Vincent Ferrer as it is being examined by what appears to be a boy. He muses on how he came to find himself in this situation, thinking back to the events in his own past life, and as he does so he becomes attached to the (apparent) boy; but people—and genders—are never what they seem to be. Or maybe they are both.

Reception

Reviews were positive :

- Elizabeth Day in The Observer concludes that "The Francesco passages are littered with poetic fragments that pull the chronology forward and back and so out-of-shape that sometimes, it is difficult to know what is happening...Personally, I preferred George's narrative and could have happily read an entire novel which consisted of a more conventional plotting of her story. I admired the Francesco passages rather than feeling engrossed by them and occasionally it felt as if Smith's ideas were so clever they were in danger of getting in the way of the story. But there is no doubt that Smith is dazzling in her daring. The sheer inventive power of her new novel pulls you through, gasping, to the final page."[7]

- Laura Miller, in The Guardian comments on duality of the novel: "While I do not doubt the two halves of How to Be Both may be read in either order with satisfying results, once read, it's impossible to know what it would be like to first encounter it in the alternate order... How to Be Both is unforgettable. I can never know what it would be like to meet George before knowing Del Cossa, so that version of the novel is forever lost to me. It's a bit sad. But it was worth it."[8]

- Arifa Akbar in The Independent also comments on the dual narrative, writing that "Smith has written a radical novel, one that becomes two novels, with discrete meanings, through its (re)ordering... How to be Both shows us that the arrangement of a story, even when it's the same story, can change our understanding of it and define our emotional attachments. We may have known this, but to see it enacted with such imagination is dazzling indeed. Those writers making doomy predictions about the death of the novel should read Smith's re-imagined novel/s, and take note of the life it contains."[9]

- Patrick Flanery of The Telegraph finds that "The pain of mourning and loss is seared into the lives of Smith’s two motherless heroines, but despite the novel’s refusal of consolation and the profound seriousness of the questions it explores, How to be Both brims with palpable joy, not only at language, literature, and art’s transformative power, but at the messy business of being human, of wanting to be more than one kind of person at once. The possibilities unleashed by the desire to be neither one thing nor the other means that one may ever and always strive to be both. With great subtlety and inventiveness, Smith continues to expand the boundaries of the novel".[10]

- Ron Charles of The Washington Post writes that "This gender-blending, genre-blurring story, bounces across centuries, tossing off profound reflections on art and grief, without getting tangled in its own postmodern wires. It’s the sort of death-defying storytelling acrobatics that don’t seem entirely possible — How did she get here from there? — but you’ve got to be willing to hang on...This sounds like a novel freighted with postmodern gimmicks, but Smith knows how to be both fantastically complex and incredibly touching."[11]

References

- Editions of How to be both by Ali Smith Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- The Man Booker Prize 2014 Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Home Page 2022 | the Rathbones Folio Prize". www.thefolioprize.com. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "New Statesman | The shortlist for the 2014 Goldsmiths Prize has been announced". New Statesman. 1 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Ali Smith wins Goldsmiths Prize for How to be Both". BBC News. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Lusher, Adam (3 June 2015). "Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction 2015 winner: Ali Smith triumphs with How to Be Both". The Independent. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- "How to Be Both by Ali Smith review – playful, tender, unforgettable | Books | The Guardian". theguardian.com. 13 September 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- How to Be Both by Ali Smith review – playful, tender, unforgettable | Books | The Guardian Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- How To Be Both by Ali Smith, book review Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- How to Be Both by Ali Smith, review: 'brimming with pain and joy' Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- Book review: ‘How to Be Both,’ by Ali Smith Retrieved 2015-02-20.