Hugo Boss

Hugo Boss AG, often styled as BOSS, is a fashion house and brand headquartered in Metzingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The company sells clothing, accessories, footwear, and fragrances. Hugo Boss is one of the largest German clothing companies,[3] with global sales of €2.9 billion in 2019.[4] Its stock is a component of the MDAX.[5]

Headquarters in Metzingen, Germany | |

| Type | Public (Aktiengesellschaft) |

|---|---|

| FWB: BOSS MDAX Component | |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 1924 |

| Founder | Hugo Boss |

| Headquarters | , Germany |

Key people | Daniel Grieder[1] (CEO) Michel Perraudin (Chairman) Lord Staci Lovell (MD) |

| Products | High-fashion Accessories Footwear |

| Revenue | €2.733 billion (2018)[2] |

| €346 million (2018)[2] | |

| €236 million (2018)[2] | |

| Total assets | €1.858 billion (2018)[2] |

| Total equity | €980 million (2018)[2] |

| Owners | Free Float (83%) Marzotto family (15%) Own shares (2%) |

Number of employees | 14,685 (31 December 2018)[2] |

| Website | www |

The company was founded in 1924 in Germany by Hugo Boss and originally produced general-purpose clothing. With the onset of the Great Depression and the rise of Nazism in the early 1930s, Boss began to produce uniforms for the Nazi Party. Boss would eventually supply the Nazi Germany government with military uniforms, resulting in a large boost in sales.[6]

After World War II and the founder's death in 1948, Hugo Boss started to turn its focus from uniforms to men's suits. The company went public in 1988 and introduced a fragrance line that same year, adding men's and women's wear diffusion lines in 1997, a full women's collection in 2000, and children's clothing in 2006–2007. The company has since evolved into a major global fashion house. As of 2018, it owned more than 1,113 retail stores worldwide.[7]

History

Early years

In 1923, Hugo Boss founded his own clothing company in Metzingen, Germany, where it still operates.[8] In 1924, he started a factory along with two partners. The company produced shirts, jackets, work clothing, sportswear, and raincoats. Due to the economic climate of Germany at the time, Boss was forced into bankruptcy. In 1931, he reached an agreement with his creditors, leaving him with six sewing machines to start again.[9]

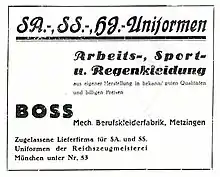

Manufacturing for the Nazi Party

That same year, Hugo Boss became a member of the Nazi Party, receiving the membership number 508 889, and a sponsoring member ("Förderndes Mitglied") of the Schutzstaffel (SS). He also joined the German Labour Front in 1936, the Reich Air Protection Association in 1939, and the National Socialist People's Welfare in 1941. He was also a member of the Reichskriegerbund and the Reichsbund for physical exercises.[10] After joining these organizations, his sales increased from 38,260 ℛ︁ℳ︁ ($26,993 U.S. dollars in 1932) to over 3,300,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ in 1941.[10] Though he claimed in a 1934–35 advertisement that he had been a "supplier for National Socialist uniforms since 1924", it is probable that he did not begin to supply them until 1928 at the earliest.[10] This is the year he became a Reichszeugmeisterei-licensed supplier of uniforms to the Sturmabteilung (SA), Schutzstaffel (SS), Wehrmacht, Hitler Youth, National Socialist Motor Corps, and other party organizations.[11][12]

By the third quarter of 1932, the all-black SS uniform was designed by SS members Karl Diebitsch (artist) and Walter Heck (graphic designer). The Hugo Boss company was one of the companies that produced these black uniforms for the SS. By 1938, the firm was focused on producing Wehrmacht uniforms and later also uniforms for the Waffen-SS.[13]

During the Second World War, Hugo Boss employed 140 forced laborers, the majority of them women. In addition to these workers, 40 French prisoners of war also worked for the company briefly between October 1940 – April 1941. According to German historian Henning Kober, the company managers were fervent Nazis who were all great admirers of Adolf Hitler. In 1945, Hugo Boss had a photograph in his apartment of him with Hitler, taken at the Berghof, Hitler's Obersalzberg retreat.[14][13]

Because of his early Nazi Party membership, his financial support of the SS, and the uniforms delivered to the Nazi party, Boss was considered both an "activist" and a "supporter and beneficiary of National Socialism". In a 1946 judgment, he was stripped of his voting rights, his capacity to run a business, and fined "a very heavy penalty" of 100,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ ($70,553 U.S.) (£54,008 stg).[10] However, Boss appealed, and he was eventually classified as a ‘follower’, a lesser category, which meant that he was not regarded as an active promoter of National Socialism.[13]

He died in 1948, but his business survived. In 2011, the company issued a statement of "profound regret to those who suffered harm or hardship at the factory run by Hugo Boss under National Socialist rule".[15]

Post-war

As a result of the ban on Boss being in business, his son-in-law Eugen Holy took over ownership and running of the company. In 1950, after a period supplying work uniforms, the company received its first order for men's suits, resulting in an expansion to 150 employees by the end of the year. By 1960, the company was producing ready-made suits. In 1969, Eugen retired, leaving the company to his sons Jochen and Uwe, who began international development. In 1970, the first Boss branded suits were produced, with the brand becoming a registered trademark in 1977. This was followed by the start of the company's long association with motorsport, sponsoring Formula One driver Niki Lauda, and later the McLaren Racing team.

In 1984, the first Boss branded fragrance appeared. This helped the company gain the required growth for listing on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange the following year. The brand began sponsorship of golf with Bernhard Langer in 1986 and tennis with the Davis Cup in 1987. In 1989, Boss launched its first licensed sunglasses. Later that year, the company was bought by a Japanese group.[16]

After the Marzotto textile group acquired a 77.5% stake for $165,000,000 in 1991,[16][17] the Hugo and Baldessarini brands were introduced in 1993. In 1995, the company launched its footwear range, the first in a now fully developed leather products range across all sub-brands. A partnership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation was launched in 1995, resulting in the Hugo Boss Prize, an annual $100,000 stipend in modern arts presented since 1996.[18]

Recent history

In 2005, Marzotto spun off its fashion brands into the Valentino Fashion Group, which was then sold to Permira private equity group. In March 2015, Permira announced plans to sell the remaining shareholding of 12%. Since the Exit by Permira, 91% of the shares floated on the Börse Frankfurt, and the residual 2% was held by the company. 7% of the shares are owned by the Marzotto family. Hugo Boss has at least 6,102 points of sale in 124 countries. Hugo Boss AG directly owns over 364 shops, 537 mono-brand shops, and over 1,000 franchisee-owned shops.[16]

In 2009, BOSS Hugo Boss was by far the largest segment, consisting of 68% of all sales. The remainder of sales were made up by Boss Orange at 17%, BOSS Selection at 3%, Boss Green at 3% and HUGO at 9%.[19]

In 2010, the company had sales of $2,345,850,000 and a net profit of $262,183,000,[16] with royalties of 42% of total net profit.[16] In June 2013, Jason Wu was named artistic director of Boss Womenswear.[20][21]

In 2017, the sales of Hugo Boss climbed by 7 percent during the final quarter of the year.[22]

Products

Hugo Boss has two core brands, Boss and Hugo.

Products are manufactured in a variety of locations, including the company's own production sites in: Metzingen, Germany; Morrovalle, Italy; Radom, Poland; Izmir, Turkey; and Cleveland, United States.[24]

Hugo Boss has invested in technology for its made-to-measure program, using machines for almost all the tailoring traditionally made by hand.[25]

Hugo Boss has licensing agreements with various companies to produce Hugo Boss branded products. These include agreements with Samsung, HTC and Huawei to produce mobile phones; Nike, Inc. to produce sports equipment; C.W.F. Children Worldwide Fashion SAS to produce children's clothing; Coty to produce fragrances and skincare;[26] Movado to produce watches;[27] and Safilo to produce sunglasses and eyewear.[28]

In 2020, Hugo Boss created its first vegan men's suit, using all non-animal materials, dyes, and chemicals.[29]

Controversies

Russell Brand

British comedian and actor Russell Brand was at the 2013 GQ awards, which were sponsored by Hugo Boss. After receiving an award on stage, Brand proceeded to talk about Hugo Boss's Nazi connection and did a goose step. He was later ejected from the ceremony and later apologized.[30]

Wages

In March 2010, Hugo Boss was boycotted by actor Danny Glover for the company's plans to close the plant in Brooklyn, Ohio, US after 375 employees of the Workers United Union reportedly rejected the Hugo Boss proposal to cut the workers' hourly wage 36% from $13 an hour to $8.30.[31] After an initial statement by CFO Andreas Stockert saying the company had a responsibility to shareholders and would move suit manufacturing from the US to other facilities in Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania,[32] the company capitulated to the boycott and cancelled the project.[33] Renewed plans to close the plant in April 2015 also failed.[34][35]

Mirror fall

In September 2015, Hugo Boss (UK) was fined £1.2 million in relation to the death in June 2013 of a child who died four days after suffering fatal head injuries at its store in Bicester, Oxfordshire.[36] The four-year-old boy had been injured when a steel-framed fitting-room mirror weighing 120 kilograms (260 lb) fell on him. Oxford Crown Court had earlier been told that it had "negligently been left free-standing without any fixings"[36] and the coroner had said that the death was an "accident waiting to happen".[37] In June 2015, Hugo Boss (UK) had admitted its breach of both the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and Management of Health and Safety at Work regulations 1999.[38] The company's legal representative said:

"The consequence of this failing is as awful as one could reasonably imagine. Since the day of the accident Hugo Boss has done all it can, first to acknowledge those failings, to express genuine, heartfelt remorse and also demonstrate a determination to put things right and ensure there cannot be a repeat of what went wrong."

— Jonathan Laidlaw QC (representing Hugo Boss)[38]

Trademark

In August 2019, Hugo Boss sent a cease & desist letter, objecting to the trademark application of Boss Brewing, a small brewery based in Swansea,[39] costing the brewery nearly £10,000 in legal fees and compelling them to change the name of several beer brands. In February 2020, professedly as a protest, comedian Joe Lycett changed his legal name to Hugo Boss.[40]

Cotton from Xinjiang

In 2020, Hugo Boss told NBC News it did not use cotton from the Xinjiang area of China to avoid Uyghur forced labor.[41] However, in 2021, the Chinese subsidiary of Hugo Boss stated on its official Sina Weibo account that they had been using cotton from the region and would continue to do so:[42][43]

"Xinjiang's long-stapled cotton is one of the best in the world. We believe top quality raw materials will definitely show its value. We will continue to purchase and support Xinjiang cotton."[44]

The statement was later edited to simply saying they have partners "in various regions of China" with a link to an English-language page on their website, which in turn linked to another statement containing the following words: "HUGO BOSS has not procured any goods originating in the Xinjiang region from direct suppliers."[45] Initially attracting thousands of likes, the edited Weibo post received many comments accusing the brand of hypocrisy.[46][47] A company spokeswoman stated that the original Weibo post was unauthorized and that the company's position has not changed.[48] According to the company's official statement, all materials are only sourced from suppliers that comply with the HUGO BOSS Supplier Code of Conduct.[45]

In September 2021, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights filed a complaint with German prosecutors accusing Hugo Boss from abetting and profiting from forced labor in Xinjiang.[49] In 2022, researchers from Nordhausen University of Applied Sciences identified cotton from Xinjiang in Hugo Boss shirts.[50]

Sponsorships

Players

Players

Matteo Berrettini (global ambassador) (from 2022)

Matteo Berrettini (global ambassador) (from 2022)

Teams

- McLaren (1987–2014)

- Mercedes-Benz (2015–2018)

- Aston Martin (2022–2025)

References

- "HUGO BOSS Group: Daniel Grieder (CEO)". group.hugoboss.com.

- "Hugo Boss Annual Report 2018" (PDF).

- "Umsatz der führenden deutschen Bekleidungshersteller im Jahr 2018". Statista (in German). September 19, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Hugo Boss Annual Report 2019" (PDF).

- "MDAX Stock | MDAX Companies | MDAX Value | Markets Insider". markets.businessinsider.com. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- Roman Köster. "Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. Eine Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und 'Drittem Reich' (Kurzfassung)" (PDF). hugoboss.com. pp. 2–4.

- "Number of Hugo Boss stores worldwide 2009–2018". Statista. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- Landler, Mark (April 12, 2005). "A Small Town in Germany Fits Hugo Boss Nicely". The New York Times. p. C00001.

- Roman, Köster (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945: Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und "Drittem Reich" (in German). Germany: C.H. Beck. p. 31. ISBN 978-3406619922.

- Timm, Elisabeth (April 12, 2018). "Hugo Ferdinand Boss (1885–1948) und die Firma Hugo Boss" (PDF). Metzingen Zwangsarbeit (in German). Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Obermaier, Frederik (September 23, 2011). "Hugo Boss in der NS-Zeit – Mode mit brauner Vergangenheit" (in German). Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- "Biografie Hugo Ferdinand Boss". Who's Who (in German). Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Köster, Roman. "Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. A Clothing Factory During the Weimar Republic and Third Reich" (PDF). Hugoboss.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2011.

- Kober, Henning (July 29, 2001). "Über den Umgang mit Zwangsarbeiterinnen bei Boss". Metzinger Zwangsarbeit (in German). Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- Hugo Boss: 'regret' for Holocaust record Jennifer Lipman, September 22, 2011,

- Chevalier, Michel (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118171769.

- "Marzotto S.p.A." The New York Times. November 2, 1991. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- "Timeline of the Hugo Boss Prize". Guggenheim. December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- "Results of Operations in Fiscal Year 2009". Hugo Boss AG. Archived from the original on September 2, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- Lance Richardson, Hugo Boss' Jason Wu breaks the rules and goes from success to success June 30, 2016

- Whitney, Christine (May 20, 2015). "How Jason Wu Became Hugo Boss's New Leading Man: The designer opens up about taking over the reigns at Boss". Harper's Bazaar.

- "The Boss Is Back". Bloomberg.com. January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- "Boss Bottled (1998)". Basenotes. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- "HUGO BOSS AG Organisational Structure". Hugo Boss AG. Archived from the original on March 23, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- Binnberg, Nils (April 11, 2017). "Techno tailor: Boss is revolutionising the made-to-measure suit". Wallpaper.com.

- "PG.com HUGO BOSS: fragrances, contemporary design, design competition". Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- "Movado Group Inc". Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- "Safilo Group S.p.A/". Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- Beth Wright, "Hugo Boss releases first vegan men's suit," just-style.com, 17 March 2020.

- "GQ award-winner Charles Moore cracks Russell Brand's 'Nazi' comment". TheGuardian.com. September 5, 2013.

- Glover, Danny (March 7, 2010). "Glover: Help Ohio Plant, Shun Hugo Boss At Oscars". Associated Press. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- Hugo Boss to move US factory production to Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, trade union says

- Covert, James (April 24, 2010). "Stars' factory crusade shows Hugo who's 'Boss'". The New York Post. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- Perkins, Olivera (December 2, 2014). "Hugo Boss says it will close Cleveland area plant in 2015, but unions ready to fight it — again". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- Perkins, Olivera (March 20, 2015). "Hugo Boss plant will stay open with new owners, saving 160+ jobs". The Plain Dealer.

- "Hugo Boss fined £1.2m over Bicester Village mirror death". BBC News Online. September 4, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- "Bicester Hugo Boss store admits charges over boy's mirror death". BBC News Online. June 3, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- Press Association (September 3, 2015). "Hugo Boss faces huge fine over toddler's death in store". The Guardian. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- "Welsh brewery spends nearly £10,000 in battle with clothing giant over name". ITV News. August 12, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- "Joe Lycett: Comedian changes his name to Hugo Boss". BBC News. March 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- Nadi, Aliza; Schecter, Anna; Martinez, Didi (September 22, 2020). "Is the cotton in your shirt from Chinese forced labor?". NBC News. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- "Is the cotton in your shirt from Chinese forced labor?". NBC News. September 22, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- "Hugo Boss, Asics will continue buying Xinjiang cotton". La Prensa Latina Media. March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- Grundy, Tom (March 26, 2021). "Hugo Boss tells Chinese customers it will continue to purchase Xinjiang cotton, months after telling US news outlet it has never used it". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- "HUGO BOSS Statement on the Chinese region of Xinjiang" (PDF).

- "Sina Visitor System". passport.weibo.com.

- Lew, Linda (March 26, 2021). "Hugo Boss' Xinjiang comments spark accusations of hypocrisy online". South China Morning Post. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- "Und Hugo Boss laviert herum ..." ZEIT ONLINE (in German). March 30, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- "Rights group files complaint against German retailers over Chinese textiles". Reuters. September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Oltermann, Philip (May 5, 2022). "Xinjiang cotton found in Adidas, Puma and Hugo Boss tops, researchers say". The Guardian. Retrieved May 6, 2022.