Hurricane Bob (1979)

Hurricane Bob was the first Atlantic tropical cyclone to be officially designated using a masculine name after the discontinuation of Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet names.[1] Bob brought moderate damage to portions of the United States Gulf Coast and areas farther inland in July 1979. The storm was the first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico to form in the month of July since 1959, and was the fifth tropical cyclone to form during the annual hurricane season. Though the origin of Bob can be traced back to a tropical wave near the western coast of Africa in late June, Bob formed from a tropical depression in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico on July 9. Tracking in a general northward direction, favorable conditions allowed for quick strengthening. Less than a day after formation, the system reached tropical storm intensity, followed by hurricane intensity on July 11. Shortly after strengthening into a hurricane, Bob reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 986 mbar (hPa; 29.12 inHg).[nb 1] At the same intensity, Bob made landfall west of Grand Isle, Louisiana, and rapidly weakened after moving inland. However, the resulting tropical depression persisted for several days as it paralleled the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. On July 16, the system emerged into the western Atlantic, where it was subsequently absorbed by a nearby low-pressure area.

Bob intensifying over the Gulf of Mexico on July 10 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 9, 1979 |

| Dissipated | July 16, 1979 |

| Category 1 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 986 mbar (hPa); 29.12 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Damage | $20 million (1979 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1979 Atlantic hurricane season | |

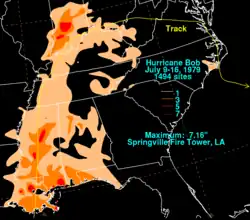

Widespread offshore and coastal evacuations took place along the United States Gulf Coast in preparation for Hurricane Bob. Effects from the hurricane on the United States were mostly marginal and typical of a minimal hurricane. The cyclone produced a moderate storm surge, damaging some coastal installments and causing coastal inundation. Strong winds were also associated with Bob's landfall, though no stations observed winds of hurricane force. The winds downed trees and blew out windows, in addition to causing widespread power outages. Heavy rainfall was also reported in some locations, peaking at 7.16 in (182 mm) in Louisiana. Further inland, the torrential rains led to flooding in Indiana, resulting in more considerable damage as opposed to the coast. Bob also spawned eight tornadoes, with two causing significant damage. Overall, Bob was responsible for one death and $20 million in damage.[nb 2]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origin of Hurricane Bob can be traced to a tropical wave that was first located near Cape Verde towards the end of June. The disturbance tracked westward with minimal signs of development, and reached the northwestern Caribbean Sea on July 6. The following day, the tropical system tracked across the Yucatán Peninsula the following day, and upon emerging into the Gulf of Mexico, the cluster of storms began to develop a weak circulation center. This enabled for more rapid tropical cyclogenesis,[2] and at 1200 UTC on July 9, the disturbance was analyzed to have organized into a tropical depression[3] – the third of such in the Atlantic that year. The depression strengthened rather quickly, and on the morning of July 10 a United States Air Force reconnaissance flight indicated that the tropical cyclone had strengthened to tropical storm intensity while situated 740 mi (1,190 km) south of Louisiana.[2] Due to the storm's intensity, the system was consequentially named Bob, making it the first Atlantic tropical cyclone to receive a masculine name since 1952.[1][4] At the time the flight measured a minimum barometric pressure of 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg).[3]

Upon reaching tropical storm intensity, Bob began to curve further northward as opposed to its prior, northeasterly track, due to the presence of a strengthening, upper-level trough to the storm's west. The trough greatly enhanced atmospheric conditions around Bob, allowing for the tropical cyclone to intensify rapidly.[2] At 0000 UTC on July 11,[3] Bob was estimated to have strengthened to hurricane intensity based on additional reconnaissance flight data.[2] This made Bob the first July hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Debra in 1959.[5] Though the hurricane's maximum sustained winds would hold steady at 75 mph (120 km/h) for approximately the ensuing twelve hours, the storm's barometric pressure would fluctuate before reaching a minimum of 981 mbar (hPa; 28.98 inHg) at 1200 UTC that day; this would be Bob's lowest documented barometric pressure. At around the same time, the hurricane made landfall west of Grand Isle, Louisiana.[2] After moving inland, Bob quickly weakened due to land interaction, and was a mere tropical depression by July 12.[3] However, the resulting depression would maintain its intensity for the next several days. On July 13, the low-pressure area drifted into southern Ohio and afterwards curved eastward. On July 16, Bob's remnants moved into the western Atlantic, where they were subsequently absorbed by another low-pressure area.[2]

Preparations

As Bob moved towards the U.S. Gulf Coast, the National Weather Service issued gale warnings for coastal regions extending from Vermilion Bay, Louisiana to Biloxi, Mississippi at 1600 UTC on July 10. These warnings were upgraded to hurricane warnings upon Bob's strengthening to such an intensity. During the storm's existence, forecasts and predictions from the National Hurricane Center were of greater accuracy than on average.[5] In addition to tropical cyclone warnings and watches, the agency also advised small craft from Port Arthur, Texas to Pensacola, Florida to remain in port.[6]

In preparation for the storm, 8,000 offshore oil workers were evacuated.[6] Despite typical evacuation procedure, Chevron Corporation immediately evacuated their offshore oil staff rather than executing a three phase evacuation plan.[7] On land, 2,500 residents and tourists on Grand Isle were also evacuated.[6] In total, as many as 80,000 people evacuated from coastal areas leading up to Bob's eventual landfall. In New Orleans, 4,000 people checked into the city's 19 evacuation centers. The Mississippi River was temporarily closed to shipping by the United States Coast Guard for eight hours before reopening after the storm.[8]

Impact

Effects in the United States as a result of Bob were typical of a minimal hurricane, and were not of considerable nature. At the coast, Bob caused moderate storm surge, resulting in coastal waters rising to as high as 5 ft (1.5 m) above normal. The rough seas sunk several boats and caused significant damage to piers.[2] A levee on Grand Isle was breached by the surge, resulting in some coastal inundation. Minor beach erosion occurred on the coast of Mississippi. In Mobile County, Alabama, the wave action damaged cars near the shore and disrupted seafood operations in the Bayou La Batre area.[9]

Strong winds were reported in association with the storm, but no station documented sustained winds within hurricane force. The highest wind observation was taken on an oil rig off the coast of Louisiana, which clocked sustained winds at 63 mph (101 km/h). However, the strongest wind gust in association with the hurricane was measured in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, at 64 mph (103 km/h).[5] In New Orleans, these strong winds damaged trees and power lines, and also broke several windows in the city's central business district.[10] In addition, widespread power outages impacted 53,000 electricity customers in the city's area. Similar incidents took place in Houma, Louisiana.[8] In Lafitte, Louisiana, two men were blown off of the roof of a marina, and one of them was killed; this would be the only death associated with the hurricane.[2] Further east, in Florida, trees and power lines were downed in Niceville.[9]

Hurricane Bob also produced a widespread area of rain that was heavy in localized areas.[11] Rainfall associated with the hurricane peaked at 7.16 in (182 mm) in Louisiana, where the storm made landfall. Statewide rainfall totals peaked at 6.64 and 4.81 in (169 and 122 mm) in Pascagoula, Mississippi and Robertsdale, Alabama, respectively.[12] Further inland, the remnants of Bob dropped heavy rainfall in the Midwestern United States, peaking at 5.72 in (145 mm) at a station in Indiana University Bloomington.[13] In addition to the strong winds and heavy rain, Bob produced eight tornadoes across the southern United States. One of these tornadoes caused $27,500 in damage after striking areas of Biloxi, Mississippi.[2] Another tornado impacted areas near Red Level, Alabama destroying or damaging several buildings and uprooting trees.[9] Overall, Hurricane Bob caused approximately $20 million in damage. However, $15 million in damage resulted from flooding in Indiana, with the rest of the storm's monetary impacts arising from coastal regions.[5]

See also

Notes

- All maximum sustained wind measurements are sustained for one minute unless otherwise noted.

- All monetary values are in 1979 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- Schmid, Randolph E. (May 27, 1979). "Men to Share Hurricane Blame". Palm Beach Post-Times. Vol. 47, no. 23. Palm Beach, Florida. Associated Press. p. A8. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- National Hurricane Center. Preliminary Report for Hurricane Bob, Page 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Severe Weather Kills 1, Injures 4". Florence Times Daily. Vol. 110, no. 193. Florence, Alabama. United Press International. July 12, 1979. p. 31. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- Hebert, Paul J. (July 1980). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1979" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 108 (7): 973–990. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108..973H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<0973:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "Hurricane Bob Is First of the Season". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 52, no. 296. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. July 11, 1979. p. 4. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- "Hurricane Bob Aims For Louisiana". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Vol. 54, no. 165. Daytona Beach, Florida. Associated Press. July 11, 1979. p. 1. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- "Hurricane Bob sweeps across Louisiana, killing one man". The Ledger. Vol. 73, no. 262. Lakeland, Florida. Associated Press. July 12, 1979. p. 3A. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- National Climatic Data Center (July 1979). "Storm Data" (PDF). Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena. Asheville, North Carolina: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 21 (7). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- National Hurricane Center. Preliminary Report for Hurricane Bob, Page 2 (Report). Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 2. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- Roth, David M. "Hurricane Bob - July 9-16, 1979". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. Silver Springs, Maryland: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- Roth, David M. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. Silver Springs, Maryland: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- Roth, David M. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Midwest". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. Silver Springs, Maryland: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved December 3, 2013.