Hurricane Hattie

Hurricane Hattie was the strongest and deadliest tropical cyclone of the 1961 Atlantic hurricane season, reaching peak intensity as a Category 5 hurricane. The ninth tropical storm, seventh hurricane, fifth major hurricane, and second Category 5 of the season, Hattie originated from an area of low pressure that strengthened into a tropical storm over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 27. Moving generally northward, the storm quickly became a hurricane and later major hurricane the following day. Hattie then turned westward west of Jamaica and strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 165 mph (270 km/h). It weakened to Category 4 before making landfall south of Belize City on October 31. The storm turned southwestward and weakened rapidly over the mountainous terrain of Central America, dissipating on November 1.

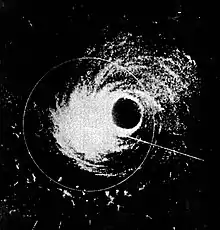

Radar image of Hurricane Hattie on October 30 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 27, 1961 |

| Dissipated | November 1, 1961 |

| Category 5 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 165 mph (270 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 914 mbar (hPa); 26.99 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 319 |

| Damage | $60.3 million (1961 USD) |

| Areas affected | British Honduras (Belize), Guatemala, Honduras |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1961 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hattie first affected the southwestern Caribbean, where it produced hurricane-force winds and caused one death on San Andres Island. It was initially forecast to continue north and strike Cuba, prompting evacuations on the island. While turning west, Hattie dropped heavy rainfall of up to 11.5 in (290 mm) on Grand Cayman. The country of Belize, at the time known as British Honduras, sustained the worst damage from the hurricane.[nb 1] The former capital, Belize City, was buffeted by strong winds and flooded by a powerful storm surge. The territory governor estimated that 70% of the buildings in the city had been damaged, leaving more than 10,000 people homeless. The destruction was so severe that it prompted the government to relocate inland to a new city, Belmopan. Overall, Hattie caused about $60 million in losses[nb 2] and 307 deaths in the territory. Although damage from Hattie was heavier than a hurricane in 1931 that killed 2,000 people, the death toll from Hattie was considerably lower as a result of early warnings. Elsewhere in Central America, Hattie killed 11 people.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

For a few days toward the end of October 1961, a low-pressure area persisted in the western Caribbean Sea, north of the Panama Canal Zone.[2] On October 25, an upper-level anticyclone moved over the low; the next day, a trough over the western Gulf of Mexico provided favorable outflow for the disturbance. At 0000 UTC on October 27, a ship nearby reported southerly winds of 46 mph (74 km/h). Later that day, the airport on San Andres Island reported easterly winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). The two observations confirmed the presence of a closed wind circulation, centered about 70 miles (110 km) southeast of San Andres, or 155 mi (249 km) east of the Nicaraguan coast; as a result, the Miami Weather Bureau began issuing advisories on the newly formed Tropical Storm Hattie.[3]

After being classified, Hattie moved steadily northward, passing very near or over San Andres Island. A station on the island recorded a pressure of 991 mbar (29.3 inHg) and sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), which indicated that Hattie had reached hurricane status.[3] Late on October 28, a Hurricane Hunters flight encountered a much stronger hurricane, with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h) in a small area near the center. At the time, gale-force winds extended outward 140 mi (230 km) to the northeast and 70 miles (110 km) to the southwest.[2] Early on October 29, a trough extending from Nicaragua to Florida was expected to allow Hattie to continue northward, based on climatology for similar hurricanes.[3] Later that day, Hattie was forecast to be an imminent threat to the Cayman Islands and western Cuba.[2] Around that time, a strengthening ridge to the north turned the hurricane northwestward, which spared the Greater Antilles but increased the threat to Central America.[3]

With the strengthening ridge to its north, Hattie began restrengthening after retaining the same intensity for about 24 hours.[3][4] Initially, forecasters at the Miami Weather Bureau predicted the storm to turn northward again. Late on October 29, the center of the hurricane passed about 90 miles (140 km) southwest of Grand Cayman, at which time the interaction between Hattie and the ridge to its north produced squally winds of around 30 mph (48 km/h) across Florida. Early on October 30, the Hurricane Hunters confirmed the increase in intensity, reporting winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[2] The storm's minimum central pressure continued to drop throughout the day, reaching 924 mbar (27.3 inHg) by 1300 UTC; a lower pressure of 920 mbar (27 inHg) was computed at 1700 UTC that day, based on a flight-level reading from the Hurricane Hunters.[3] Hattie later curved toward the west-southwest, passing between the Cayman Islands and the Swan Islands. Late on October 30, Hattie attained peak winds of 165 mph (266 km/h), concomitantly with a minimum central pressure of 914 mbar (27.0 inHg), about 190 mi (310 km) east of the border of Mexico and British Honduras. This made Hattie a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, making it the latest hurricane on record to reach the status until a reanalysis of the 1932 season revealed that Hurricane Fourteen had a similar intensity on November 5, six days after Hattie.[4] Additionally, Hattie was the strongest October hurricane in the northwest Caribbean until Hurricane Mitch in 1998.[5]

Hattie maintained much of its intensity as it continued toward the coast of British Honduras. After moving through several small islands offshore, the hurricane made landfall a short distance south of Belize City on October 31, with an eyewall of about 25 miles (40 km) in diameter.[3] Based on a post-season analysis, it was determined that Hattie had weakened to winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) before moving ashore. During landfall, a ship anchored between Belize City and Stann Creek registered a minimum central pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg).[4] The hurricane deteriorated rapidly over land, dissipating on November 1 as it moved into the mountains of Guatemala. During its dissipation, Tropical Storm Simone was developing off the Pacific coast of Guatemala,[3][4] however, later analysis concluded that Simone was not a tropical cyclone at all. Later, Tropical Storm Inga formed from a complex interaction with the remnants of Hattie and nearby disturbed weather.[6]

Preparations

Upon initiating advisories on Hattie, the Miami Weather Bureau noted the potential for heavy rainfall and flash flooding in the southwestern Caribbean. The advisories recommended for small vessels to remain at harbor across the region.[2] Initially, the hurricane was predicted to move near or through the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, and Cuba.[3] As a result, Cuban officials advised residents in low-lying areas to evacuate.[7]

Hurricane Hattie first posed a threat to the Yucatán Peninsula and British Honduras on October 30 when it turned toward the area.[2] Officials at the Miami Weather Bureau warned of the potential for high tides, strong winds, and torrential rainfall. The warnings allowed for extensive evacuations in high-risk areas.[2] Most people in the capital, Belize City, were evacuated or moved to shelters,[3] and a school was operated as a refuge.[8] A hospital in the city was evacuated,[9] and over 75% of the population of Stann Creek fled to safer locations.[3] After Hattie made landfall, officials in Mexico ordered the closure of ports along the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[9]

Impact

_(20345898205).jpg.webp)

Despite predictions for heavy rainfall in the southwestern Caribbean, the hurricane's movement was more northerly than expected, resulting in less precipitation along the Central American coast than anticipated.[2] In its early developmental stages, Hattie struck San Andrés Island, located offshore eastern Nicaragua, with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and gusts of 104 mph (167 km/h). As the hurricane neared the island, the airport was closed due to tropical-storm-force winds.[3] Rough seas and winds damaged private property and two hotels. Many palm tree plantations were devastated. The schooner Admirar, anchored in one of the island's bays, capsized during the storm.[10] Overall, Hattie resulted in one death, fifteen injuries, and $300,000 in damage (1961 USD) in San Andrés. The hurricane was the fourth on record to strike the island, and of the four was the only to approach from the south.[3]

In the northwestern Caribbean, Hattie passed close to Grand Cayman with heavy rainfall. At least 11.5 inches (290 mm) of rain were reported on the island, including 7.8 inches (200 mm) in six hours.[2] Winds on Grand Cayman were below hurricane force, and only minor damage occurred due to the rain.[2]

The interaction between Hattie and the ridge of high pressure to its north produced sustained winds of 20 mph (32 km/h) across most of Florida, with a gust of 72 mph (116 km/h) reported at Hillsboro Inlet Light; the winds caused some beach erosion in the state.[2] The U.S. Weather Bureau issued a small craft warning for the west and east Florida coastlines, as well as northward to Brunswick, Georgia.[11]

Later, Hattie impacted various countries in Central America with flash floods, causing 11 deaths in Guatemala and one fatality in Honduras.[3] The Swan Islands reported wind gusts just below hurricane force, resulting in minor damage and one injury.[2]

British Honduras

Hurricane Hattie moved ashore in British Honduras with a storm tide of up to 14 feet (4.3 m) near Belize City,[3] a city of 31,000 people located at sea level; its only defenses against the storm tide were a small seawall and a strip of swamp lands.[12] The capital experienced high waves and a 10 ft (3 m) storm tide along its waterfront that reached the third story of some buildings. A trained observer estimated winds of over 150 mph (240 km/h), and winds in the territory were unofficially estimated as strong as 200 mph (320 km/h).[3] When Hattie affected the area, most buildings in Belize City were wooden, and most of this type were destroyed.[9] Offshore, the hurricane heavily damaged 80% of the Belize Barrier Reef, although the reef recovered after the storm. [13]

High winds caused a power outage,[12] downed trees across the region, and destroyed the roofs of many buildings.[14] Governor Colin Thornley estimated that more than 70% of the buildings in the territory were damaged, and more than 10,000 people were left homeless.[9] Some shelters set up before the storm were destroyed in the hurricane.[2] The hurricane destroyed the wall at an insane asylum, which allowed the residents to escape.[14] High waves damaged a prison,[15] prompting officials to institute a "daily parole" program for the inmates.[14] Hattie also flooded the Government House, washing away all records.[15] All of Belize City was coated in a layer of mud and debris,[14] and majority of the city was destroyed or severely damaged, as was nearby Stann Creek.[3] The hurricane left significant crop damage across the region, including $2 million in citrus fruits and similar losses to timber, cocoa, and bananas.[3] The year's production of sugar cane was also heavily damaged. About 70% of the territory's mahogany trees were downed, as were most citrus and grapefruit trees. The hurricane damaged several factories and oil rigs in the region.[16] Damage throughout the territory totaled $60 million (1961 USD),[3] and a total of 307 deaths were reported;[17] more than 100 of the fatalities were in Belize City,[2] including 36 who evacuated to a British administration building that was later destroyed in the storm.[18] The government of British Honduras considered Hurricane Hattie more damaging than a hurricane in 1931 that killed 2,000 people; the lower death toll of Hattie was due to advance warning.[3]

Aftermath

After Hattie struck, officials in Belize City declared martial law.[9] A manager of United Press International described Belize City as "nothing but a huge pile of matchsticks,"[9] and many roads were either flooded for days or covered with mud.[19] Doctors provided typhoid vaccinations to 12,000 residents in two days to prevent the spread of the disease. Due to the high death toll, officials ordered mass cremations to stop additional disease from spreading.[20] At the city's police station, workers provided fresh water and rice to storm victims.[9] Many residents throughout British Honduras donated supplies to the storm victims, such that an airlines manager described it as "taxing ... manpower and facilities." One airline allowed donations to be flown to Belize City at no cost.[16] The city's three newspapers were unable to operate due to lack of power after the storm.[16] By November 5, Belize City's post office reopened on a limited basis, and all business initially remained closed. About 4,000 homeless residents from Stann Creek were moved by boat to the northern portion of the territory.[18] Many homeless people from the Belize City area set up a tent city on bushland about 16 mi (26 km) inland, which was initially intended to be temporary.[18][21] In December 1961, barracks were erected near a Red Cross Hospital to house the homeless in the camp. The site was named Hattieville and became a proper city, with utilities installed in the subsequent decade.[21]

About 200 British soldiers arrived from Jamaica to quell looting and maintain order.[18][20] At least 20 people were arrested in the day after Hattie struck.[15] The British government sent flights of aid to the territory containing food, clothing, and medical supplies.[9] The House of Commons quickly passed a bill to provide £10,000 in aid. The Save the Children fund sent £1,000 to British Honduras,[22] and the Mexican government sent three flights with food and medicine to the territory.[9] Two American destroyers arrived in the country by November 2, reporting the need for assistance.[9] The USS Antietam remained at port for weeks after the storm with six medical officers and six Marine helicopters. Four other ships sailed to the territory to provide 458,000 pounds (208,000 kg) of food.[20][23] The United States government allocated about $300,000 in assistance through the International Development Association.[22] The Canadian government provided C$75,000 worth of aid, including food, blankets, and medical supplies.[24]

In 1962, Jimmy Cliff released his breakthrough single, "Hurricane Hattie".[25][26] By Hattie's one year anniversary, private and public workers repaired and rebuilt buildings affected by the storm. New hotels were constructed, and many stores were reopened. Prime Minister George Cadle Price successfully appealed for assistance from the British government, which ultimately provided £20 million in loans.[27] In the days after the storm, the government announced plans to relocate the capital of British Honduras farther inland on higher ground. Work on the new capital, Belmopan, was completed in 1970.[8][28] On the 44th anniversary of the hurricane in 2005, the government of Belize unveiled a monument in Belize City to recognize the victims of the hurricane.[29]

Due to the destruction and loss of life attributed to the hurricane, the name Hattie was retired by the World Meteorological Organization and will never again be used for an Atlantic hurricane; the name was replaced by Holly in 1965.[30]

See also

Notes

- British Honduras, formerly a British Overseas Territory, attained its independence in 1981 and became the country of Belize.[1] The territory is referred to as British Honduras in the article.

- All damage totals are in 1961 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- "Belize country profile". BBC Country Profiles. BBC News. 2012-08-02. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- Hurricane Hattie: October 27–31, 1961 (PDF) (Preliminary Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1962-01-04. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- Dunn, Gordon E. (1962-03-01). "The Hurricane Season of 1961" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 90 (3): 107–119. Bibcode:1962MWRv...90..107D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1962)090<0107:THSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT) (Database). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Guiney, John L.; Lawrence, Miles B. (1999-01-28). Hurricane Mitch: 22 October–05 November 1998 (Preliminary Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- Caparotta, Stephen; Walston, D.; Young, Steven; Padgett, Gary; Delgado, Sandy (2011-05-31). "E15: What tropical storms and hurricanes have moved from the Atlantic to the Northeast Pacific or Vice Versa?". In Landsea, Chris; Dorst, Neal (eds.). Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.5. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- "'Cane Hattie Threatens Western Cuba, Florida". The Palm Beach Post. Vol. 53, no. 223. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. 1961-10-30. p. 1. Retrieved 2020-03-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ediger, Theodore A. (1961-11-05). "Battered School Shelters 200 Refugees in Belize". The Evening Independent. Vol. 3, no. 29. Belize City, British Honduras. Associated Press. p. 3A. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "Hattie's Toll is 62: Martial Law Declared". St. Petersburg Times. Vol. 78. Belize City, British Honduras. United Press International. 1961-11-02. pp. 1A, 2A. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- "Analasis de vulnerabilidad" (PDF). Plan de Emergencia Para La Atención de Huracanes (Report) (in Spanish). Comité Regional de Prevención y Atención de Desastres. 2008. p. [19]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- "Full-Fledged Hattie Kicking Up a Fuss". The Miami News. 1961-10-28. p. 1A. Retrieved 2020-03-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Disaster Feared in Honduras". Reading Eagle. No. 277. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. 1961-10-31. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- Spalding, Mark D.; Ravilious, Corinna; Green, Edward Peter (2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. University of California Press. p. 119. ISBN 0520232550. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- Winfrey, Lee (1961-11-02). "Belize All But Wiped Out by Hurricane Hattie". The Bonham Daily Favorite. Vol. 69, no. 63. Belize City, British Honduras. United Press International. p. 5. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- Rosenbury, Morris W. (1961-11-01). "Hurricane Toll Runs High". Gadsden Times. Vol. 95, no. 98. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "Hattie Dealt Industry Deadly Blow". The Palm Beach Post. Vol. 28, no. 43. Belize, British Honduras. Associated Press. 1961-11-05. p. 8. Retrieved 2020-03-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- NEMO Press Officer (2006-11-02). "Belize Marked 45th Anniversary of Deadly Hurricane Hattie" (Press release). Belize National Emergency Management Organization (NEMO). Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- "Belize Toll Rises to 204". The Palm Beach Post. Vol. 28, no. 43. Belize, British Honduras. Associated Press. 1961-11-05. p. 8. Retrieved 2020-03-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Belize Toll Reaches 225". The Calgary Herald. Calgary, Alberta. Canadian Press. 1961-11-06. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "Mass Cremations for Belize Victims". The Windsor Star. Vol. 87, no. 55. Belize City, British Honduras. 1961-11-06. p. 21. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- Pridgeon, Elizabeth (2009-11-13). "Hattieville". The Belize Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- "Hurricane Deaths May Total 1000". The Glasgow Herald. Vol. 179, no. 242. 1961-11-04. p. 7. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "U.S. Navy Ships Leave Storm-Hit Honduras Area". The Florence Times. Vol. 102, no. 221. Norfolk, Virginia. Associated Press. 1961-11-06. p. 8. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "Canada to Aid Honduras with $75,000 Supplies". The Calgary Herald. Ottawa, Quebec. Canadian Press. 1961-11-08. p. 61. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- Matt Parker (July 22, 2013). "Jimmy Cliff on a life in songwriting". Music Radar. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Greene, Jo-Ann. "Jimmy Cliff Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- "Marks of Storm are Rare Today". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Vol. 34, no. 308. Belize, British Honduras. Associated Press. 1962-11-04. p. 3F. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- "Hurricane 'Edith' Deepens Rapidly". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Vol. 46, no. 342. Associated Press. 1971-09-07. pp. 1A, 4A. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- NEMO Press Officer (2005-10-31). "Monument to Remember 1961 Hurricane Hattie Unveiled" (Press release). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- Padgett, Gary; Beven, Jack; Free, James L.; Delgado, Sandy (2011-05-31). "B3: What storm names have been retired?". In Landsea, Chris; Dorst, Neal (eds.). Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.5. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2013-05-12.