1936 Mid-Atlantic hurricane

The 1936 Mid-Atlantic hurricane (also referred to as 1936 Outer Banks hurricane) was the most intense tropical cyclone of the 1936 Atlantic hurricane season, paralleling areas of the United States East Coast in September 1936. The thirteenth tropical cyclone and eighth hurricane of the year, the storm formed from a tropical disturbance in the central Atlantic Ocean on September 9.[1] Peaking as a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale, the hurricane abruptly recurved out to sea near Virginia on September 18 without ever making landfall and transitioned into a hurricane-strength extratropical cyclone early the next day.[2]

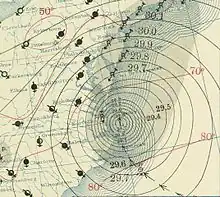

Surface weather analysis of the storm on September 18 at its closest approach to the United States | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 8, 1936 |

| Extratropical | September 19 |

| Dissipated | September 25, 1936 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 962 mbar (hPa); 28.41 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Damage | $4.05 million (1936 USD) |

| Areas affected | United States East Coast, Atlantic Canada |

Part of the 1936 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On September 9, ships observed signs of a potentially developing tropical disturbance in the central Atlantic Ocean. The first reports of such convective activity in the area were relayed by the S.S. West Selene at 00:00 UTC that day.[1] Based on this report, tropical cyclogenesis was estimated to have completed by 06:00 UTC on September 8; a reanalysis of the storm conducted in 2012 did not find any justification to alter the date in HURDAT,[nb 1] and as such the initial date of formation remained unchanged.[2] The tropical depression was quick to intensify, and was analyzed to have attained tropical storm strength by 18:00 UTC later that day. At the time, the system was tracking northwestward.[4] The following day, ships continued to report rough seas generated by the storm approximately 250 mi (400 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[1] On September 10, westerly winds south of the storm's estimated position were reported, confirming the existence of a closed circulation center and justifying the system's classification as a fully-tropical cyclone.[2] Gradual intensification continued, and at 00:00 UTC on September 12, it is estimated that the tropical storm intensified to hurricane intensity. At roughly the same time, the hurricane also began to track a more northerly course.[4]

Moving through favorable conditions for tropical cyclone development, intensification continued, and it is estimated that the hurricane reached an intensity equivalent to that of a modern-day Category 2 hurricane by 12:00 UTC on September 14.[4] In addition, the storm began to curve back towards the northwest – a course which would continue up until the cyclone's closest approach to the United States. Later that day, intensification began to quicken as the hurricane expanded in size.[1][2] Despite a much higher intensity suggested by the storm's estimated strength at the time, the lowest recorded barometric pressure that day was only 998 mbar (hPa; 29.74 inHg).[2] The hurricane attained modern-day Category 3 hurricane by 12:00 UTC the next day, classifying it as a major hurricane. Shortly after, the storm reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h); this intensity would be maintained for at least the following 18 hours.[4] On the morning of September 16, it was estimated that winds of at least force 6 on the Beaufort scale spanned an area up to 1,000 mi (1,600 km) in diameter, making it one of the largest documented tropical cyclones at the time.[1] Over the next day, the hurricane gradually weakened as it approached the United States East Coast.[4] On September 18, the storm began to parallel the East Coast of the United States.[1] At 06:00 UTC that day, it was estimated that the hurricane had a minimum central pressure of 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg) based on observations recorded by two ships within the radius of maximum winds;[2] this would be the lowest pressure listed in the storm's HURDAT entry.[4] It was estimated that the hurricane made its closest approach to the United States at 10:00 UTC that day when it was 50 mi (85 km) off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. At the time, the tropical cyclone was the equivalent of a modern-day Category 2 hurricane with maximum winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 964 mbar (hPa; 28.47 inHg).[2][4] The hurricane passed roughly the same distance from the Virginia coastline before abruptly recurving off to sea.[2]

As it began to recurve away from the Eastern Seaboard, the hurricane continued to weaken. The tropical cyclone was analyzed to have weakened to a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale by 18:00 UTC on September 18. Due to its continued progression towards more northerly latitudes, the hurricane began to transition into an extratropical cyclone — a process which was completed by 12:00 UTC on September 19.[2][4] Afterwards, the transitioned cyclone began to trek eastward.[4] The extratropical system retained winds equivalent to that of a hurricane until after 00:00 UTC on September 22. For reasons which remain unclear, the cyclone drastically slowed in forward speed and began heading towards the north until September 25, by which time the storm resumed its easterly bearing. The system was estimated to have dissipated by 18:00 UTC that day, as the low-pressure area became extremely large and broad in its circulation.[2]

Preparations

On September 16, the United States Weather Bureau cautioned ships in the path of the hurricane, stating that the storm was the "most intense" of the year.[5] As the hurricane neared the U.S. coast, storm warnings were issued for coastal regions between Southport, North Carolina and the Virginia Capes on September 17.[6] Shortly after, northwest storm warnings were issued for portions of the North Carolina coast south of Beaufort. Later that day, storm warnings between Beaufort, North Carolina and Manteo were upgraded to hurricane warnings; these warnings were later extended to include areas between Beaufort and Wilmington, North Carolina.[1][7] Later that day, northeast storm warnings were extended northward to Atlantic City, New Jersey. Following the extratropical transition of the hurricane, all warnings north of the Virginia Capes to Sandy Hook, New Jersey were changed to whole gale warnings on September 18; these warnings were later extended northward to Provincetown, Massachusetts. All warnings were discontinued by the time the extratropical storm moved out of the area.[1]

Prior to the storm, the American Red Cross and other local relief agencies began preparations for a potential emergency in the aftermath of the hurricane.[7] The United States Coast Guard dispatched ten cutters to the southern U.S. Atlantic coast to monitor and prepare to render aid to other ships in the path of the approaching hurricane.[8]

Impact

Atlantic Ocean

While in the central Atlantic, the Norwegian steamship Torvangen was struck by turbulent seas caused by the hurricane 500 mi (800 km) north of Puerto Rico, disabling the ship's rudder and forcing water into the Torvanger's holds. Though no distress call was relayed by the steamer, the steamship Noravind was dispatched to assist the crew of the slowly capsizing ship.[9][10] The United States Coast Guard cutter Unalaga and the Panamanian steamship F.J. Wolfe were also dispatched to assess the situation.[10] After temporary impromptu repairs were made, the Torvangen was escorted to Bermuda.[11]

Nova Scotia

Passing south of Nova Scotia from September 21–22, the extratropical remnants of the hurricane caused heavy rainfall. Precipitation peaked at 7 in (180 mm). In Kentville, the rains heavily reduced visibility, leading to a car accident; three people were injured as a result. In the Annapolis Valley, the rains caused thousands of dollars in damage to grain crops. However, apple crops in the region were unaffected. Floodwaters caused Wrights River Lake in Antigonish to overflow its banks. A person attempting to swim in the lake later drowned. In Liver Pool, the rains disrupted communication networks and flooded gardens and cellars. Rivers overflowed their banks in Truro, flooding flats. Numerous roads in the province were flooded and washed out. In Shelburne, roads were inundated under 3 ft (1 m) of water.

See also

- Hurricane Helene (1958) – Strong Category 4 hurricane that caused widespread devastation on the United States East Coast without making landfall

- Hurricane Able (1951) – Preseason hurricane that produced hurricane-force winds on the coast

- Hurricane Barbara (1953) –Moved through Pamlico Sound and only briefly moved inland as it affected populations from North Carolina to Canada

- List of Category 3 Atlantic hurricanes

Notes

- HURDAT is the official hurricane database used by the National Hurricane Center which lists track data on tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean of at least tropical storm strength since 1851.[3]

References

- Tannehill, I.R.; United States Weather Bureau's Marine Division (September 1936). "Tropical Disturbances, September 1936" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 64 (9): 297–299. Bibcode:1936MWRv...64..297T. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1936)64<297:TDS>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Landsea, Chris; Atlantic Oceanic Meteorological Laborartory (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (2006). "NOAA Revisits Historic Hurricanes". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Hurricane Likely To Miss Florida". The Telegraph-Herald. Vol. 98, no. 57. Dubuque, Iowa. Associated Press. September 16, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Hurricane Moving Toward U.S. Coast". Prescott Evening Courier. Prescott, Arizona. Associated Press. September 17, 1936. p. 2. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Hurricane Will Rake Seaboard, Bureau Advises". The Tuscaloosa News. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Associated Press. September 17, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Ten U.S. Cutters Ready To Give Aid". The Tuscaloosa News. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Associated Press. September 17, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Hurricane Batters Norwegian Steamer". Lewiston Evening Journal. Vol. 74. Lewiston, Maine. Associated Press. September 15, 1936. p. 6. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Season's Worst Hurricane Roars On Shipping Lanes". The Painsville Telegraph. Vol. 115, no. 52. Painesville, Ohio. Associated Press. September 15, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Disabled Boat Limps To Port". Sarasota Herald. Vol. 11, no. 295. Sarasota, Florida. Associated Press. September 15, 1936. p. 6. Retrieved 17 June 2013.