Hydnoroideae

Hydnoroideae is a subfamily of parasitic flowering plants in the order Piperales. Traditionally, and as recently as the APG III system it given family rank under the name Hydnoraceae.[1] It is now submerged in the Aristolochiaceae.[2][3] It contains two genera, Hydnora and Prosopanche:[2]

- Prosopanche is native to Central and South America ;

- Hydnora can be found in semi-arid to desert regions of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and Madagascar.

| Hydnoroideae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prosopanche americana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Piperales |

| Family: | Aristolochiaceae |

| Subfamily: | Hydnoroideae Walpers |

| Genera | |

| |

| Hydnoroideae distribution map | |

Members of this subfamily have been described as the strangest plants in the world.[4]

Description

The most striking aspect of the Hydnoroideae is probably the complete absence of leaves (not even in modified forms such as scales).[2] Some species are mildly thermogenic (capable of producing heat), presumably as a means of dispersing their scent.[5]

Morphology in pictures

Hydnora johannis, young plant in Um Barona, Wad Medani, Sudan.

Hydnora johannis, young plant in Um Barona, Wad Medani, Sudan. Hydnora triceps, roots at Gemsbokvlei Farm, Wolfberg Road, southeast of Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2003

Hydnora triceps, roots at Gemsbokvlei Farm, Wolfberg Road, southeast of Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2003 Flower of Hydnora africana in Karasburg District, Namibia, 2002.

Flower of Hydnora africana in Karasburg District, Namibia, 2002. Emerging flower of Hydnora africana in a desert dominated by Euphorbia mauritanica near Fish River Canyon, in the south of Namibia, 2000

Emerging flower of Hydnora africana in a desert dominated by Euphorbia mauritanica near Fish River Canyon, in the south of Namibia, 2000 Hydnora johannis in flower in Um Barona, Wad Medani, Sudan

Hydnora johannis in flower in Um Barona, Wad Medani, Sudan Flowers of Hydnora triceps in Namaqualand, South Africa, 1999

Flowers of Hydnora triceps in Namaqualand, South Africa, 1999 Hydnora triceps, freshly cut fruit near Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2002

Hydnora triceps, freshly cut fruit near Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2002 Hydnora triceps, hollowed out mature fruit near Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2002

Hydnora triceps, hollowed out mature fruit near Port Nolloth, South Africa, 2002

Ecology

The plants are pollinated by insects such as dermestid beetles or carrion flies, attracted by the fetid odor of the flowers.[2] In Hydnora africana there are bait bodies with a strong smell, whereas in Hydnora johannis the scent comes from a region at the tip of the perianth called a cucullus.[2] The flowers may be above ground or underground.[2] The fruits have edible, fragrant pulp, which attracts animals such as porcupines, monkeys, jackals, rhinoceros, and armadillos, as well as humans. The host plants, in the case of Hydnora, generally are in the family Euphorbiaceae and the genus Acacia.[2] Hosts for Prosopanche include various species of Prosopis and other legumes.

Genomics

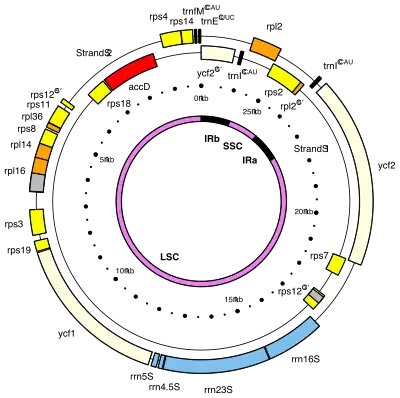

The complete plastid genome sequence of one species of Hydnoroideae, Hydnora visseri, has been determined. As compared to the chloroplast genome of its closest photosynthetic relatives, the plastome of Hydnora visseri shows extreme reduction in both size (27,233 bp) and gene content (24 genes appear to be functional).[7] The plastome of Hydnora visseri is therefore one of the smallest among flowering plants.[8]

Classification

Like many parasitic plants, the affinities with non-parasitic plants are not obvious, and 19th and 20th century botanists proposed a variety of placements for the taxon. Molecular data places them in the Piperales, and nested within the Aristolochiaceae and allied with the Piperaceae or Saururaceae.[3][2][9][10]

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x.

- Nickrent, D. L.; Blarer, A.; Qiu, Y.-L.; Soltis, D. E.; Soltis, P. S.; Zanis, M. (2002), "Molecular data place Hydnoraceae with Aristolochiaceae", American Journal of Botany, 89 (11): 1809–17, doi:10.3732/ajb.89.11.1809, PMID 21665609

- The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2016), "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 181: 1–10, doi:10.1111/boj.12385

- Musselman, L.J.; Visser, J.H. (1986-12-01). "The strangest plant in the world". Veld & Flora. 72 (4). ISSN 0042-3203.

- Seymour, Rs; Maass, E; Bolin, Jf (Jul 2009), "Floral thermogenesis of three species of Hydnora (Hydnoraceae) in Africa", Annals of Botany, 104 (5): 823–32, doi:10.1093/aob/mcp168, ISSN 0305-7364, PMC 2749535, PMID 19584128

- The Genus Hydnora

- Naumann, Julia; Der, Joshua P.; Wafula, Eric K.; Jones, Samuel S.; Wagner, Sarah T.; Honaas, Loren A.; Ralph, Paula E.; Bolin, Jay F.; Maass, Erika; Neinhuis, Christoph; Wanke, Stefan; dePamphilis, Claude W. (2016-02-01). "Detecting and Characterizing the Highly Divergent Plastid Genome of the Nonphotosynthetic Parasitic Plant Hydnora visseri (Hydnoraceae)". Genome Biology and Evolution. 8 (2): 345–363. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv256. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 4779604. PMID 26739167.

- List of sequenced plastomes: Flowering plants.

- Barkman, Tj; Mcneal Jr; Lim, Sh; Coat, G; Croom, Hb; Young, Nd; Depamphilis, Cw (Dec 2007), "Mitochondrial DNA suggests at least 11 origins of parasitism in angiosperms and reveals genomic chimerism in parasitic plants", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 7: 248, doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-248, PMC 2234419, PMID 18154671

- Corradi, Nicolas; Naumann, Julia; Salomo, Karsten; Der, Joshua P.; Wafula, Eric K.; Bolin, Jay F.; Maass, Erika; Frenzke, Lena; Samain, Marie-Stéphanie; Neinhuis, Christoph; dePamphilis, Claude W.; Wanke, Stefan (2013). "Single-Copy Nuclear Genes Place Haustorial Hydnoraceae within Piperales and Reveal a Cretaceous Origin of Multiple Parasitic Angiosperm Lineages". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e79204. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879204N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079204. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3827129. PMID 24265760.