Hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word hymn derives from Greek ὕμνος (hymnos), which means "a song of praise". A writer of hymns is known as a hymnist. The singing or composition of hymns is called hymnody. Collections of hymns are known as hymnals or hymn books. Hymns may or may not include instrumental accompaniment.

Although most familiar to speakers of English in the context of Christianity, hymns are also a fixture of other world religions, especially on the Indian subcontinent (stotras). Hymns also survive from antiquity, especially from Egyptian and Greek cultures. Some of the oldest surviving examples of notated music are hymns with Greek texts.

Origins

Ancient Eastern hymns include the Egyptian Great Hymn to the Aten, composed by Pharaoh Akhenaten; the Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal; the Rigveda, an Indian collection of Vedic hymns; hymns from the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), a collection of Chinese poems from 11th to 7th centuries BC; the Gathas—Avestan hymns believed to have been composed by Zoroaster; and the Biblical Book of Psalms.

The Western tradition of hymnody begins with the Homeric Hymns, a collection of ancient Greek hymns, the oldest of which were written in the 7th century BC, praising deities of the ancient Greek religions. Surviving from the 3rd century BC is a collection of six literary hymns (Ὕμνοι) by the Alexandrian poet Callimachus. The Orphic hymns are a collection of 87 short poems in Greek religion.

Patristic writers began applying the term ὕμνος, or hymnus in Latin, to Christian songs of praise, and frequently used the word as a synonym for "psalm".[1]

Christian hymnody

Originally modelled on the Book of Psalms and other poetic passages (commonly referred to as "canticles") in the Scriptures, Christian hymns are generally directed as praise to the Christian God. Many refer to Jesus Christ either directly or indirectly.

Since the earliest times, Christians have sung "psalms and hymns and spiritual songs", both in private devotions and in corporate worship.[2] Non-scriptural hymns (i.e. not psalms or canticles) from the Early Church still sung today include 'Phos Hilaron', 'Sub tuum praesidium', and 'Te Deum'.

One definition of a hymn is "...a lyric poem, reverently and devotionally conceived, which is designed to be sung and which expresses the worshipper's attitude toward God or God's purposes in human life. It should be simple and metrical in form, genuinely emotional, poetic and literary in style, spiritual in quality, and in its ideas so direct and so immediately apparent as to unify a congregation while singing it."[3]

Christian hymns are often written with special or seasonal themes and these are used on holy days such as Christmas, Easter and the Feast of All Saints, or during particular seasons such as Advent and Lent. Others are used to encourage reverence for the Bible or to celebrate Christian practices such as the eucharist or baptism. Some hymns praise or address individual saints, particularly the Blessed Virgin Mary; such hymns are particularly prevalent in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy and to some extent High Church Anglicanism.

A writer of hymns is known as a hymnodist, and the practice of singing hymns is called hymnody; the same word is used for the collectivity of hymns belonging to a particular denomination or period (e.g. "nineteenth century Methodist hymnody" would mean the body of hymns written and/or used by Methodists in the 19th century). A collection of hymns is called a hymnal, hymn book or hymnary. These may or may not include music; among the hymnals without printed music, some include names of hymn tunes suggested for use with each text, in case readers already know the tunes or would like to find them elsewhere. A student of hymnody is called a hymnologist, and the scholarly study of hymns, hymnists and hymnody is hymnology. The music to which a hymn may be sung is a hymn tune.

In many Evangelical churches, traditional songs are classified as hymns while more contemporary worship songs are not considered hymns. The reason for this distinction is unclear, but according to some it is due to the radical shift of style and devotional thinking that began with the Jesus movement and Jesus music. In recent years, Christian traditional hymns have seen a revival in some churches, usually more Reformed or Calvinistic in nature, as modern hymn writers such as Keith and Kristyn Getty[4] and Sovereign Grace Music have reset old lyrics to new melodies, revised old hymns and republished them, or simply written a song in a hymn-like fashion such as In Christ Alone.[5]

Music and accompaniment

In ancient and medieval times, string instruments such as the harp, lyre and lute were used with psalms and hymns.

Since there is a lack of musical notation in early writings,[6] the actual musical forms in the early church can only be surmised. During the Middle Ages a rich hymnody developed in the form of Gregorian chant or plainsong. This type was sung in unison, in one of eight church modes, and most often by monastic choirs. While they were written originally in Latin, many have been translated; a familiar example is the 4th century Of the Father's Heart Begotten sung to the 11th century plainsong Divinum Mysterium.

Western church

Later hymnody in the Western church introduced four-part vocal harmony as the norm, adopting major and minor keys, and came to be led by organ and choir. It shares many elements with classical music.

Today, except for choirs, more musically inclined congregations and a cappella congregations, hymns are typically sung in unison. In some cases complementary full settings for organ are also published, in others organists and other accompanists are expected to adapt the available setting, or extemporise one, on their instrument of choice.

In traditional Anglican practice, hymns are sung (often accompanied by an organ) during the processional to the altar,[7] during the receiving of communion, during the recessional, and sometimes at other points during the service. The Doxology is also sung after the tithes and offerings are brought up to the altar.

Contemporary Christian worship, as often found in Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism, may include the use of contemporary worship music played with electric guitars and the drum kit, sharing many elements with rock music.

Other groups of Christians have historically excluded instrumental accompaniment, citing the absence of instruments in worship by the church in the first several centuries of its existence, and adhere to an unaccompanied a cappella congregational singing of hymns. These groups include the 'Brethren' (often both 'Open' and 'Exclusive'), the Churches of Christ, Mennonites, several Anabaptist-based denominations—such as the Apostolic Christian Church of America—Primitive Baptists, and certain Reformed churches, although during the last century or so, several of these, such as the Free Church of Scotland have abandoned this stance.

Eastern church

Eastern Christianity (the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches) has a variety of ancient hymnographical traditions. In the Byzantine Rite, chant is used for all forms of liturgical worship: if it is not sung a cappella, the only accompaniment is usually an ison, or drone. Organs and other instruments were excluded from church use, although they were employed in imperial ceremonies.[8] However, instruments are common in some other Oriental traditions. The Coptic tradition makes use of the cymbals and the triangle only. The Indian Orthodox (Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church) use the organ. The Tewahedo Churches use drums, cymbals and other instruments on certain occasions.

Development of Christian hymnody

Thomas Aquinas, in the introduction to his commentary on the Psalms, defined the Christian hymn thus: "Hymnus est laus Dei cum cantico; canticum autem exultatio mentis de aeternis habita, prorumpens in vocem." ("A hymn is the praise of God with song; a song is the exultation of the mind dwelling on eternal things, bursting forth in the voice.")[9]

The Protestant Reformation resulted in two conflicting attitudes towards hymns. One approach, the regulative principle of worship, favoured by many Zwinglians, Calvinists and some radical reformers, considered anything that was not directly authorised by the Bible to be a novel and Catholic introduction to worship, which was to be rejected. All hymns that were not direct quotations from the Bible fell into this category. Such hymns were banned, along with any form of instrumental musical accompaniment, and organs were removed from churches. Instead of hymns, biblical psalms were chanted, most often without accompaniment, to very basic melodies. This was known as exclusive psalmody. Examples of this may still be found in various places, including in some of the Presbyterian churches of western Scotland.

The other Reformation approach, the normative principle of worship, produced a burst of hymn writing and congregational singing. Martin Luther is notable not only as a reformer, but as the author of hymns including "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" ("A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"), "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" ("Praise be to You, Jesus Christ"), and many others. Luther and his followers often used their hymns, or chorales, to teach tenets of the faith to worshipers. The first Protestant hymnal was published in Bohemia in 1532 by the Unitas Fratrum.

Count Zinzendorf, the Lutheran leader of the Moravian Church in the 18th century wrote some 2,000 hymns.

The earlier English writers tended to paraphrase biblical texts, particularly Psalms; Isaac Watts followed this tradition, but is also credited as having written the first English hymn which was not a direct paraphrase of Scripture.[10] Watts (1674–1748), whose father was an Elder of a dissenter congregation, complained at age 16, that when allowed only psalms to sing, the faithful could not even sing about their Lord, Christ Jesus. His father invited him to see what he could do about it; the result was Watts' first hymn, "Behold the glories of the Lamb".[11] Found in few hymnals today, the hymn has eight stanzas in common meter and is based on Revelation 5:6, 8, 9, 10, 12.[12]

Relying heavily on Scripture, Watts wrote metered texts based on New Testament passages that brought the Christian faith into the songs of the church. Isaac Watts has been called "the father of English hymnody", but Erik Routley sees him more as "the liberator of English hymnody", because his hymns, and hymns like them, moved worshipers beyond singing only Old Testament psalms, inspiring congregations and revitalizing worship.[13]

Later writers took even more freedom, some even including allegory and metaphor in their texts.

Charles Wesley's hymns spread Methodist theology, not only within Methodism, but in most Protestant churches. He developed a new focus: expressing one's personal feelings in the relationship with God as well as the simple worship seen in older hymns.

Wesley's contribution, along with the Second Great Awakening in America led to a new style called gospel, and a new explosion of sacred music writing with Fanny Crosby, Lina Sandell, Philip Bliss, Ira D. Sankey, and others who produced testimonial music for revivals, camp meetings, and evangelistic crusades. The tune style or form is technically designated "gospel songs" as distinct from hymns. Gospel songs generally include a refrain (or chorus) and usually (though not always) a faster tempo than the hymns. As examples of the distinction, "Amazing Grace" is a hymn (no refrain), but "How Great Thou Art" is a gospel song. During the 19th century, the gospel-song genre spread rapidly in Protestantism and to a lesser but still definite extent, in Roman Catholicism; the gospel-song genre is unknown in the worship per se by Eastern Orthodox churches, which rely exclusively on traditional chants (a type of hymn).

The Methodist Revival of the 18th century created an explosion of hymn-writing in Welsh, which continued into the first half of the 19th century. The most prominent names among Welsh hymn-writers are William Williams Pantycelyn and Ann Griffiths. The second half of the 19th century witnessed an explosion of hymn tune composition and congregational four-part singing in Wales.[14]

Along with the more classical sacred music of composers ranging from Charpentier (19 Hymns, H.53 - H.71) to Mozart to Monteverdi, the Catholic Church continued to produce many popular hymns such as Lead, Kindly Light, Silent Night, O Sacrament Most Holy, and Faith of Our Fathers.

In some radical Protestant movements, their own sacred hymns completely replaced the written Bible. An example of this, the Book of Life (Russian: "Zhivotnaya kniga") is the name of all oral hymns of the Doukhobors, the Russian denomination, similar to western Quakers. The Book of Life of the Doukhobors (1909) is firstly printed hymnal containing songs, which to have been composed as an oral piece to be sung aloud.[15]

Many churches today use contemporary worship music which includes a range of styles often influenced by popular music. This often leads to some conflict between older and younger congregants (see contemporary worship). This is not new; the Christian pop music style began in the late 1960s and became very popular during the 1970s, as young hymnists sought ways in which to make the music of their religion relevant for their generation.

This long tradition has resulted in a wide variety of hymns. Some modern churches include within hymnody the traditional hymn (usually describing God), contemporary worship music (often directed to God) and gospel music (expressions of one's personal experience of God). This distinction is not perfectly clear; and purists remove the second two types from the classification as hymns. It is a matter of debate, even sometimes within a single congregation, often between revivalist and traditionalist movements.

Swedish composer and musicologist Elisabet Wentz-Janacek mapped 20,000 melody variants for Swedish hymns and helped create the Swedish Choral Registrar, which displays the wide variety of hymns today.[16]

In modern times, hymn use has not been limited to strictly religious settings, including secular occasions such as Remembrance Day, and this "secularization" also includes use as sources of musical entertainment or even vehicles for mass emotion.[17]

American developments

Hymn writing, composition, performance and the publishing of Christian hymnals were prolific in the 19th-century and were often linked to the abolitionist movement by many hymn writers. Stephen Foster wrote a number of hymns that were used during church services during this era of publishing.

Thomas Symmes spread throughout churches a new idea of how to sing hymns, in which anyone could sing a hymn any way they felt led to; this idea was opposed by the views of Symmes' colleagues who felt it was "like Five Hundred different Tunes roared out at the same time". William Billings, a singing school teacher, created the first tune book with only American born compositions. Within his books, Billings did not put as much emphasis on "common measure" which was the typical way hymns were sung, but he attempted "to have a Sufficiency in each measure". Boston's Handel and Haydn Society aimed at raising the level of church music in America, publishing their "Collection of Church Music". In the late 19th century Ira D. Sankey and Dwight L. Moody developed the relatively new subcategory of gospel hymns.[18]

Earlier in the 19th century, the use of musical notation, especially shape notes, exploded in America, and professional singing masters went from town to town teaching the population how to sing from sight, instead of the more common lining out that had been used before that. During this period hundreds of tune books were published, including B.F. White's Sacred Harp, and earlier works like the Missouri Harmony, Kentucky Harmony, Hesperian Harp, D.H. Mansfield's The American Vocalist, The Social Harp, the Southern Harmony, William Walker's Christian Harmony, Jeremiah Ingalls' Christian Harmony, and literally many dozens of others. Shape notes were important in the spread of (then) more modern singing styles, with tenor-led 4-part harmony (based on older English West Gallery music), fuging sections, anthems and other more complex features. During this period, hymns were incredibly popular in the United States, and one or more of the above-mentioned tunebooks could be found in almost every household. It is not uncommon to hear accounts of young people and teenagers gathering together to spend an afternoon singing hymns and anthems from tune books, which was considered great fun, and there are surviving accounts of Abraham Lincoln and his sweetheart singing together from the Missouri Harmony during his youth.

By the 1860s musical reformers like Lowell Mason (the so-called "better music boys") were actively campaigning for the introduction of more "refined" and modern singing styles, and eventually these American tune books were replaced in many churches, starting in the Northeast and urban areas, and spreading out into the countryside as people adopted the gentler, more soothing tones of Victorian hymnody, and even adopted dedicated, trained choirs to do their church's singing, rather than having the entire congregation participate. But in many rural areas the old traditions lived on, not in churches, but in weekly, monthly or annual conventions were people would meet to sing from their favorite tunebooks. The most popular one, and the only one that survived continuously in print, was the Sacred Harp, which could be found in the typical rural Southern home right up until the living tradition was "re-discovered" by Alan Lomax in the 1960s (although it had been well-documented by musicologist George Pullen Jackson prior to this). Since then there has been a renaissance in "Sacred Harp singing", with annual conventions popping up in all 50 states and in a number of European countries recently, including the UK, Germany, Ireland and Poland, as well as in Australia.[19][20][21]

Black America's hymns

African-Americans developed a rich hymnody from spirituals during times of slavery to the modern, lively black gospel style. The first influences of African-American culture into hymns came from slave songs of the United States a collection of slave hymns, compiled by William Francis Allen, who had difficulty pinning them down from the oral tradition, and though he succeeded, he points out the awe-inspiring effect of the hymns when sung in by their originators.[22] Some of the first hymns in the black church were renderings of Isaac Watts hymns written in the African-American vernacular English of the time.[23]

Hymn meters

The meter indicates the number of syllables for the lines in each stanza of a hymn. This provides a means of marrying the hymn's text with an appropriate hymn tune for singing. In practice many hymns conform to one of a relatively small number of meters (syllable count and stress patterns). Care must be taken, however, to ensure that not only the metre of words and tune match, but also the stresses on the words in each line. Technically speaking an iambic tune, for instance, cannot be used with words of, say, trochaic metre.

The meter is often denoted by a row of figures besides the name of the tune, such as "87.87.87", which would inform the reader that each verse has six lines, and that the first line has eight syllables, the second has seven, the third line eight, etc. The meter can also be described by initials; L.M. indicates long meter, which is 88.88 (four lines, each eight syllables long); S.M. is short meter (66.86); C.M. is common metre (86.86), while D.L.M., D.S.M. and D.C.M. (the "D" stands for double) are similar to their respective single meters except that they have eight lines in a verse instead of four.[24]

Also, if the number of syllables in one verse differ from another verse in the same hymn (e.g., the hymn "I Sing a Song of the Saints of God"), the meter is called Irregular.

Hindu hymnody

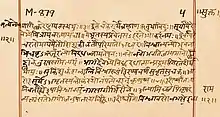

The Rigveda is the earliest and foundational Indian collection of over a thousand liturgical hymns in Vedic Sanskrit.[25]

Between other notable Hindu hymns (stotras and others) or their collections there are:

- Naalayira Divya Prabandham

- Ram Raksha Stotra

- Saundarya Lahari

- Shiva Stuti

- Shiva Tandava Stotram

- Tirumurai

- Vayu Stuti

A hymnody acquired tremendous importance during the medieval era of the bhakti movements. When the chanting (bhajan and kirtan) of the devotional songs of the poet-sants (Basava, Chandidas, Dadu Dayal, Haridas, Hith Harivansh, Kabir, Meera Bai, Namdev, Nanak, Ramprasad Sen, Ravidas, Sankardev, Surdas, Vidyapati) in local languages in a number of groups, namely Dadu panth, Kabir panth, Lingayatism, Radha-vallabha, Sikhism, completely or significantly replaced all previous Sanskrit literature. The same and with the songs of Baul movement. That is, the new hymns themselves received the status of holy scripture. An example of a hymnist, both lyricist and composer is the 15th–16th centuries Assamese reformer guru Sankardev with his borgeet-songs.[26][27]

Sikh hymnody

The Sikh holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ Punjabi pronunciation: [ɡʊɾu ɡɾəntʰ sɑhɪb]), is a collection of hymns (Shabad) or Gurbani describing the qualities of God[28] and why one should meditate on God's name. The Guru Granth Sahib is divided by their musical setting in different ragas[29] into fourteen hundred and thirty pages known as Angs (limbs) in Sikh tradition. Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), the tenth guru, after adding Guru Tegh Bahadur's bani to the Adi Granth[30][31] affirmed the sacred text as his successor, elevating it to Guru Granth Sahib.[32] The text remains the holy scripture of the Sikhs, regarded as the teachings of the Ten Gurus.[33] The role of Guru Granth Sahib, as a source or guide of prayer,[34] is pivotal in Sikh worship.

In other religions

Buddhism

Confucianism

The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry, the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), were initially lyrics.[35] The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.[36]

Islam

Jainism

Judaism

Shinto

Zoroastrianism

Appreciations

According to Nissim Ezekiel, views on hymns can be divided:

...poets who have mystical experiences and project them in verse have occasionally been successful but mystics who write poetry do it badly. Religious hymns, however notable the religious sentiment they express are not notably poetic. Great religious poetry undoubtedly exists but the greatness is unequally divided between the poetry and religion, while perfect integration between the two is rare.[37]

See also

References

- Entry on ὕμνος, Liddell and Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 8th edition 1897, 1985 printing), p. 1849; entry on 'hymnus,' Lewis and Short, A Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1879, 1987 printing), p. 872.

- Bible, (Matthew 26:30; Mark 14:26; Acts 16:25; 1 Cor 14:26; Ephesians 5:19; Colossians 3:16; James 5:13; cf. Revelation 5:8–10; Revelation 14:1–5

- Eskew; McElrath (1980). Sing with Understanding, An Introduction to Christian Hymnology. Broadman Press. ISBN 0-8054-6809-9.

- "In praise of hymns". Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Songs of faith, retrieved 18 May 2017

- Anderson, Warren; Mathiesen, Thomas J.; Boynton, Susan; Ward, Tom R.; Caldwell, John; Temperley, Nicholas; Eskew, Harry (2001). Hymn. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.13648. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Processional Hymns, for Use in the Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, New York | Hymnary.org. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Levy, Kenneth; Troelsgård, Christian (2016). Troelsgård, Christian (ed.). "Byzantine chant". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.04494. ISBN 9781561592630. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Aquinas, Thomas. "St. Thomas's Introduction to his Exposition of the Psalms of David". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- Wilson-Dickson, Andrew (1992). The Story of Christian Music. Oxford: Lion, SPCK. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-281-04626-3.

- Routley, Erik (1980). Christian Hymns, An Introduction to Their Story (Audio Book). Princeton: Prestige Publications, Inc. p. Part 7, "Isaac Watts, the Liberator of English Hymnody".

- Routley and Richardson (1979). A Panorama of Christian Hymnody. Chicago: G.I.A. Publications, Inc. pp. 40–41. ISBN 1-57999-352-4.

- Christian Hymns, An Introduction to Their Story (Audio Book) op. cit. p. Part 7, "Isaac Watts, the Liberator of English Hymnody".

- E. Wyn James, 'The Evolution of the Welsh Hymn', in Dissenting Praise, ed. I. Rivers & D. L. Wykes (Oxford University Press, 2011); E. Wyn James, 'Popular Poetry, Methodism, and the Ascendancy of the Hymn', in The Cambridge History of Welsh Literature, ed. Geraint Evans & Helen Fulton (Cambridge University Press, 2019); E. Wyn James, 'German Chorales and American Songs and Solos: Contrasting Chapters in Welsh Congregational Hymn-Singing', The Bulletin of the Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 295, Vol. 22:2 (Spring 2018), 43–53.

- Peacock, Kenneth, ed. (1970). Songs of the Doukhobors: An Introductory Outline (PDF). National Museums of Canada Bulletin No. 231, Folklore Series No. 7. Translated by E. A. Popoff (song texts). Ottawa: The National Museums of Canada; Queen's Printer of Canada.

- "Vi gratulerar Elisabet Wentz-Janacek!". Lunds domkyrka (in Swedish). 21 January 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Adey, Lionel (1986). Hymns and the Christian Myth. UBC Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-7748-0257-4.

- Music, David. Hymnology A Collection of Source Readings. 1. 1. Lanham MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1996.

- "Sacred Harp Bremen". www.sacredharpbremen.org. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Macadam, Edwin and Sheila. "Welcome". www.ukshapenote.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Sacred Harp in Poland | Polish Sacred Harp Community Website". sacredharp86.org (in Polish). Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Music, David. Hymnology A Collection of Source Readings. 1. 1. Lanham MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1996. 179/185–186/192/199/206. Print.

- Salamone, Frank A. (2004). Levinson, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals. New York: Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 0-415-94180-6.

- Children's Britannica. Vol. 9 (Revised 3rd ed.). 1981. pp. 166–167.

- The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Vol. 1. Translated by Stephanie W. Jamison; Joel P. Brereton. New York: Oxford University Press. 2014. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H., eds. (1987). The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Berkeley Religious Studies Series. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3. OCLC 925707272.

- Sivaramkrishna, M.; Roy, Sumita, eds. (1996). Poet-Saints of India. New Delhi: Sterling Publ. ISBN 81-207-1883-6.

- Penney, Sue (1995). Sikhism. Heinemann. p. 14. ISBN 0-435-30470-4.

- Brown, Kerry (1999). Sikh Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 0-415-20288-4.

- Ganeri, Anita (2003). The Guru Granth Sahib and Sikhism. Black Rabbit Books. p. 13.

- Kapoor, Sukhbir (2005). Guru Granth Sahib an Advance Study. Hemkunt Press. p. 139.

- Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2005). Introduction to World Religions. p. 223.

- Kashmir, Singh. Sri Guru Granth Sahib — A Juristic Person. Global Sikh Studies. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Singh, Kushwant (2005). A history of the sikhs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-567308-5.

- Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilisation: A Sourcebook (2nd ed.). New York: The Free Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-02-908752-7.

- Cai, Zong-qi (July 1999). "In Quest of Harmony: Plato and Confucius on Poetry". Philosophy East and West. 49 (3): 317–345. doi:10.2307/1399898. JSTOR 1399898.

- Ezekiel, Nizzim (1987). Critical Thought: An Anthology of Twentieth Century Indian English Essay. New Delhi: Sterling Publishing. p. 230.

Further reading

- Bradley, Ian. Abide with Me: the World of Victorian Hymns. London: S.C.M. Press, 1997. ISBN 0-334-02703-9

- Hughes, Charles, Albert Christ Janer, and Carleton Sprague Smith, eds. American Hymns, Old and New. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. 2 vols. N.B.: Vol. l, [the music, harmonized, with words, of the selected hymns of various Christian denominations, sects, and cults]; vol. 2, Notes on the Hymns and Biographies of the Authors and Composers. ISBN 0-231-05148-4 set comprising both volumes.

- Weddle, Franklyn S. How to Use the Hymnal. Independence, Mo.: Herald House, 1956.

- Wren, Brian. "Praying Twice: The Music and Words of Congregational Song". Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. ISBN 0-664-25670-8

- H. A. Hodges (ed. E. Wyn James), Flame in the Mountains: Williams Pantycelyn, Ann Griffiths and the Welsh Hymn (Tal-y-bont: Y Lolfa, 2017), 320 pp. ISBN 978-1-78461-454-6.

External links

The links below are restricted to either material that is historical or resources that are non-denominational or inter-denominational. Denomination-specific resources are mentioned from the relevant denomination-specific articles.

- "The Hymn Society in the United States and Canada". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007.

- "Hymnary.org". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2020.—Extensive database of hymns and hymnology resources; incorporates the Dictionary of North American Hymnology

- "Hymns Without Words – a collection of freely downloadable recordings of classic hymns for use in congrgational singing".

- "The Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland".

- "Examples of Byzantine Music for Hymns". Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2006.—2000 pages of hymns in both staff and neumatic notation

- "HistoricHymns.com".—Site with extensive hymn searching tools