I'm Not in Love

"I'm Not in Love" is a song by British group 10cc, written by band members Eric Stewart and Graham Gouldman. It is known for its innovative and distinctive backing track, composed mostly of the band's multitracked vocals. Released in the UK in May 1975 as the second single from the band's third album, The Original Soundtrack, it became the second of the group's three number-one singles in the UK between 1973 and 1978, topping the UK Singles Chart for two weeks. "I'm Not in Love" became the band's breakthrough hit outside the United Kingdom, topping the charts in Canada and the Republic of Ireland as well as peaking within the top ten of the charts in several other countries, including Australia, Germany, New Zealand, Norway and the United States.

| "I'm Not in Love" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

One of the side-A labels of the original 1975 UK single | ||||

| Single by 10cc | ||||

| from the album The Original Soundtrack | ||||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released | May 1975 | |||

| Recorded | 1974–1975 | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | 10cc | |||

| 10cc singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Written mostly by Stewart as a response to his wife's declaration that he did not tell her often enough that he loved her, "I'm Not in Love" was originally conceived as a bossa nova song played on guitars, but the other two members of the band, Kevin Godley and Lol Creme, were not impressed with the idea for the track and it was abandoned. However, after hearing members of their staff continue to sing the melody around their studio, Stewart persuaded the group to give the song another chance, to which Godley replied that for the song to work it needed to be radically changed, and suggested that the band should try to create a new version using just voices.

Writing and composition

Stewart came up with the idea for the song after his wife, to whom he had been married for eight years at that point, asked him why he did not say "I love you" more often to her. Stewart said, "I had this crazy idea in my mind that repeating those words would somehow degrade the meaning, so I told her, 'Well, if I say every day "I love you, darling, I love you, blah, blah, blah", it's not gonna mean anything eventually'. That statement led me to try to figure out another way of saying it, and the result was that I chose to say 'I'm not in love with you', while subtly giving all the reasons throughout the song why I could never let go of this relationship."[6]

Stewart wrote most of the melody and the lyrics on the guitar before taking it to the studio, where Gouldman offered to help him complete the song. Gouldman suggested some different chords for the melody, and also came up with the intro and the bridge section of the song. Stewart said that the pair spent two or three days writing the song, which at that point had a bossa nova rhythm and used principally guitars, before playing it to Godley and Creme. Stewart recorded a version with the other three members playing the song in the studio on traditional instruments – Creme on guitar, Gouldman on bass, and Godley on drums – but Godley and Creme disliked the song, particularly Godley, as Stewart later recalled: "He said, 'It's crap', and I said, 'Oh right, OK, have you got anything constructive to add to that? Can you suggest anything?' He said, 'No. It's not working, man. It's just crap, right? Chuck it.' And we did. We threw it away and we even erased it, so there's no tape of that bossa nova version."[6]

Having abandoned "I'm Not in Love", Stewart and Gouldman turned their attention to the track "Une Nuit A Paris", which Godley and Creme had been working on and which would later become the opening track on The Original Soundtrack album. However, Stewart noticed that members of staff in the band's Strawberry Studios were still singing the melody of "I'm Not in Love", and this convinced him to ask the other members of the group to consider reviving the song. Godley was still sceptical, but came up with a radical idea, telling Stewart, "I tell you what, the only way that song is gonna work is if we totally fuck it up and we do it like nobody has ever recorded a thing before. Let's not use instruments. Let's try to do it all with voices."[6] Although taken aback by the suggestion, Stewart and the others agreed to try Godley's idea and create "a wall of sound" of vocals that would form the focal point of the record.[7]

Recording

Stewart spent three weeks recording Gouldman, Godley and Creme singing "ahhh" 16 times for each note of the chromatic scale, building up a "choir" of 48 voices for each note of the scale. The main problem facing the band was how to keep the vocal notes going for an infinite length of time, but Creme suggested that they could get around this issue by using tape loops. Stewart created loops of about 12 feet in length by feeding the loop at one end through the tape heads of the stereo recorder in the studio, and at the other end through a capstan roller fixed to the top of a microphone stand, and tensioned the tape. By creating long loops the 'blip' caused by the splice in each tape loop could be drowned out by the rest of the backing track, providing that the splices in each loop did not coincide with each other. Having created twelve tape loops for each of the 12 notes of the chromatic scale, Stewart played each loop through a separate channel of the mixing desk. This effectively turned the mixing desk into a musical instrument complete with all the notes of the chromatic scale, which the four members together then "played", fading up three or four channels at a time to create "chords" for the song's melody. Stewart had put tape across the bottom of each channel so that it was impossible to completely fade down the tracks for each note, resulting in the constant background hiss of vocals heard throughout the song.[7] Composer and music theory professor Thomas MacFarlane considered the resulting "ethereal voices" with distorted synthesized effects to be a major influence on Billy Joel's hit ballad "Just the Way You Are", released two years later.[8]

A basic guide track was recorded first in order to help create the melody using the vocals, but the proper instrumentation was added after the vocals had been recorded. In keeping with Godley's idea to focus on the voices, only a few instruments were used: a Fender Rhodes electric piano played by Stewart, a Gibson 335 electric guitar played by Gouldman for the rhythm melody, and a bass drum sound played by Godley on a Moog synthesizer which Creme had recently purchased and learned how to program. The drum sound that was created was very soft and more akin to a heartbeat, in order not to overpower the rest of the track. Creme played piano during the bridge and the middle eight, where it replicated the melody of lyrics that had been discarded. The middle eight is also the only part of the song that contains a bass guitar line, played by Gouldman. A toy music box was recorded and double tracked out of phase for the middle eight and the outro.[7]

Once the musical backing had been completed Stewart recorded the lead vocal and Godley and Creme the backing vocals, but even though the song was finished Godley felt it was still lacking something. Stewart said, "Lol remembered he had said something into the grand piano mics when he was laying down the solos. He'd said 'Be quiet, big boys don't cry' — heaven knows why, but I soloed it and we all agreed that the idea sounded very interesting if we could just find the right voice to speak the words. Just at that point the door to the control room opened and our secretary Kathy Redfern looked in and whispered 'Eric, sorry to bother you. There's a telephone call for you.' Lol jumped up and said 'That's the voice, her voice is perfect!'."[6] The group agreed that Redfern was the ideal person, but Redfern was unconvinced and had to be coaxed into recording her vocal contribution, using the same whispered voice that she had used when entering the control room. These whispered lyrics would later serve as the inspiration for the name of the 1980s band Boys Don't Cry.[9]

Release and promotion

According to Stewart, at the time of recording The Original Soundtrack the band was already being courted by Mercury Records (part of the Phonogram group) to leave Jonathan King's small UK Records label, where they were struggling financially. He said: "I rang them. I said come and have a listen to what we've done, come and have a listen to this track. And they came up and they freaked, and they said, 'This is a masterpiece. How much money, what do you want? What sort of a contract do you want? We'll do anything.' On the strength of that one song, we did a five-year deal with them for five albums and they paid us a serious amount of money."[10] Despite impressing their new label with the track, Phonogram felt that it was not suitable for release as a single due to its length, and released "Life Is a Minestrone" as the first single from The Original Soundtrack instead. However, many influential figures in the music industry were demanding that "I'm Not in Love" be released as a single, and Mercury eventually bowed to the pressure and released it as the second single from the album. The band were forced to edit the track down to four minutes for radio play, but once it charted, pressure from the public and the media caused the radio stations to revert to playing the full version.[6] Record World said that "One of the most technically perfect productions of this or any year is kind of a cross between '2001' and the golden era Lennon-McCartney ballad days."[11]

Released in May 1975, "I'm Not in Love" became the band's second number-one, staying atop the UK singles chart for two weeks from 28 June. In the US, the record peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks, deprived of an expected[12] top spot placing by a different number-one each week (Van McCoy's "The Hustle", The Eagles' "One of These Nights", and the Bee Gees' "Jive Talkin'"). In the UK the single was released in its full length version of over six minutes; in the US and Canada it was released in an edited 3:42 version, and with a different B-side.

Legacy

"I'm Not in Love" has enjoyed lasting popularity, with over three million plays on US radio since its release, and it won three Ivor Novello Awards in 1976 for Best Pop Song, International Hit of the Year, and Most Performed British Work.[7][13] It has appeared in numerous films and television shows, most famously in Guardians of the Galaxy. Queen Latifah recorded a cover for her album Trav'lin' Light,[14] and a cover version by Kelsey Lu was featured in the TV series Euphoria.[15]

Axl Rose cited it as a song that meant a lot to him as a teenager: "So nonchalant, so cool ....".[16]

Italian-Brazilian singer Deborah Blando release a Portuguese version of the song called "Somente o Sol", in 1998.

Personnel

Adapted from the liner notes of The Original Soundtrack.[17]

- Eric Stewart – lead vocal, electric piano

- Graham Gouldman – guitar, bass guitar, backing vocals

- Kevin Godley – Moog, backing vocals

- Lol Creme – piano, backing vocals

- Kathy Redfern – uncredited whisperings : Big Boys Don't Cry

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications and sales

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[45] | Gold | 400,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Will to Power version

| "I'm Not in Love" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Will to Power | ||||

| from the album Journey Home | ||||

| B-side | "Fly Bird", "It's My Life" | |||

| Released | 29 June 1990 | |||

| Length | 3:48 | |||

| Label | Epic | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Will to Power singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

American musical group Will to Power covered the song for their second studio album, Journey Home, releasing as the first single from the album in 1990. It reached the top ten on the pop charts of the US, Canada, Norway, and Portugal.

Track listing

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I'm Not in Love" | 3:48 |

| 2. | "Fly Bird" (Reprise) | 3:46 |

| 3. | "It's My Life" | 5:23 |

Weekly charts

| Chart (1990–1991) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[46] | 38 |

| Canada Top Singles (RPM)[47] | 7 |

| Canada Adult Contemporary (RPM)[48] | 3 |

| Europe (Eurochart Hot 100)[49] | 78 |

| Germany (Official German Charts)[50] | 48 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[51] | 27 |

| New Zealand (Recorded Music NZ)[52] | 15 |

| Norway (VG-lista)[53] | 8 |

| Portugal (AFP)[54] | 6 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[55] | 29 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[56] | 7 |

| US Adult Contemporary (Billboard)[57] | 4 |

10cc acoustic version

| "I'm Not in Love" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by 10cc | ||||

| from the album Mirror Mirror | ||||

| B-side | "Blue Bird" | |||

| Released | 1995 | |||

| Length | 3:30 | |||

| Label | Avex UK | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | 10cc, Rod Gammons | |||

| 10cc singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

In 1995, Eric Stewart and Graham Gouldman re-recorded "I'm Not in Love" as an acoustic version for the last 10cc studio album Mirror Mirror. It was released as a single and charted at #29 in the UK[62] giving the band the highest position since "Dreadlock Holiday" in 1978.

Track listing

- "I'm Not in Love (Acoustic Session '95)" - 3:30

- "I'm Not in Love (Rework of Art Mix)" - 5:51

- "Blue Bird" (Graham Gouldman) - 4:04

Deni Hines version

| "I'm Not in Love" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Deni Hines | ||||

| from the album Imagination | ||||

| Released | 1996 | |||

| Length | 6:02 | |||

| Label | Festival Mushroom Records | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | Ian Green | |||

| Deni Hines singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

In 1996, the Australian singer songwriter Deni Hines released "I'm Not in Love" as the fourth single from her debut album Imagination (1996). At the ARIA Music Awards of 1997, "I'm Not in Love" was nominated for two awards - ARIA Award for Best Female Artist losing to "Mary" by Monique Brumby and ARIA Award for Best Pop Release losing to "To the Moon and Back" by Savage Garden.[63]

Track listing

- "I'm Not in Love"

- "It's Alright" (quiet summertime version)

- "Joy" (full testament mix)

- "It's Alright" (summertime remix)

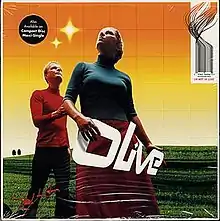

Olive version

| "I'm Not in Love" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Olive | ||||

| from the album Trickle | ||||

| Released | 27 June 2000 | |||

| Recorded | 1999 | |||

| Genre | Trip hop | |||

| Length | 4:39 | |||

| Label | Maverick | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Olive singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Following their debut album, the English trip hop band Olive recorded a cover of the song. At the cusp of their new record contract with Maverick Records at the time, the band debuted the song on the label's soundtrack for the Madonna film The Next Best Thing before releasing it as the debut single from their second album, Trickle.

Fronted by the lone vocals of singer Ruth-Ann Boyle, the song simulated the backing tracks of the original; the most audible modification made to the song is a percussion track in the style of drum and bass, turning the song into an upbeat dance track.

Accompanied by dance-oriented remixes on the single release, the song gained sufficient nightclub play to reach number one on the Billboard Hot Dance Music/Club Play chart (on the week of 1 July 2000),[64] as well as airplay on dance-hits format radio.[65]

References

- Breithaupt, Don; Breithaupt, Jeff (2000), Night Moves: Pop Music in the Late '70s, St. Martin's Press, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-312-19821-3

- Pitchfork Staff (22 August 2016). "The 200 Best Songs of the 1970s". Pitchfork. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

"I'm Not in Love" is one of the sentiments rarely voiced in pop...

- Pelly, Jenn (16 August 2013). "Watch: Twin Shadow Covers 10cc's "I'm Not In Love"". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "VH1's 40 Most Softsational Soft-Rock Songs". Stereogum. SpinMedia. 31 May 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/top-70s-songs/

- Buskin, Richard (June 2005). "Classic Tracks: 10cc – 'I'm Not in Love'". Sound on Sound. Cambridge, England: SOS Publications: 62–69. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Presenters: Richard Allinson and Steve Levine (9 May 2009). "The Record Producers – 10cc". The Record Producers. Season 3. Episode 4. BBC. BBC Radio 2.

- MacFarlane, Thomas (16 October 2016). Experiencing Billy Joel: A Listener's Companion. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1-4422-5769-6.

- Popson, Tom (15 August 1986). "Boys Don't Cry Hit Trail, Counter 'Cowboy' Image". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "I Write The Songs". The10ccfanclub.com. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Hits of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 26 April 1975. p. 1. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- Casey Kasem, American Top 40, 19 July 1975

- "1976". The Ivors. 11 May 1976. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- James, Steve (12 October 2007). "Just A Minute With: Queen Latifah". Reuters.

- Maicki, Salvatore. "Kelsey Lu takes on 10cc "I'm Not In Love"". The Fader.

- Wall, Mick (January 2002). "Eve of destruction". Classic Rock. No. 36. p. 95.

- The Original Soundtrack (liner notes). 10cc. Mercury. 1975. 9102 500.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. p. 307. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love" (in French). Ultratop 50.

- "RPM Top 100 Singles - August 23, 1975" (PDF).

- "RPM Top 50 Pop - August 23, 1975" (PDF).

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts.

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – I'm Not in Love". Irish Singles Chart.

- "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 27, 1975" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love". Top 40 Singles.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love". VG-lista.

- "SA Charts 1965–March 1989". Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Salaverri, Fernando (2015). Sólo éxitos 1959–2012 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. p. 194. ISBN 978-84-8048-866-2.

- "10cc – I'm Not in Love". Swiss Singles Chart.

- "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company.

- "10cc Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- Whitburn, Joel (1993). Top Adult Contemporary: 1961–1993. Record Research. p. 238.

- Hoffman, Frank (1983). The Cash Box Singles Charts, 1950-1981. Scarecrow Press. p. 592. ISBN 0-8108-1595-8.

- "National Top 100 Singles for 1975". Kent Music Report. 29 December 1975. Retrieved 15 January 2022 – via Imgur.

- "Jaaroverzichten 1975" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Lyttle, Brendan (27 December 1975). "1975 Wrap Up – Top 200 singles of 1975 as compiled from RPM charts". RPM. 24 (14). Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 1975". Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Single 1975" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Hung Medien. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "Top Selling Singles of 1975 | The Official New Zealand Music Chart". Nztop40.co.nz. 31 December 1975. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "1975 Best Sellers: Singles". Record Mirror and Disc. London, England: Spotlight Publications. 10 January 1976. p. 12.

- "Pop Singles". Billboard ("Talent in Action" supplement). 27 December 1975. p. 8.

- "Top 100 Year End Charts: 1975". Cash Box. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "British single certifications – 10cc – I'm Not in Love". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "Will to Power – I'm Not in Love". ARIA Top 50 Singles.

- "Top RPM Singles: Issue 1448." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 1456." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 8, no. 4. 26 January 1991. p. 27. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Will to Power – I'm Not in Love" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts.

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – I'm Not in Love". Irish Singles Chart.

- "Will to Power – I'm Not in Love". Top 40 Singles.

- "Will to Power – I'm Not in Love". VG-lista.

- "Top 10 in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 8, no. 7. 16 February 1991. p. 18. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company.

- "Will to Power Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- "Will to Power Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard.

- "RPM 100 Hit Tracks of 1991". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. 21 December 1991. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "RPM 100 Adult Contemporary Tracks of 1991". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. 21 December 1991. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "1991 The Year in Music & Video: Top Pop Singles". Billboard. Vol. 103, no. 51. 21 December 1991. p. YE-14.

- "1991 The Year in Music" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 103, no. 51. 21 December 1991. p. YE-36. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- "10 C.C." officialcharts.com. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "ARIA Awards – History: Winners by Year 1997". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). Hot Dance/Disco: 1974–2003. Record Research. p. 193.

- Ball, Joann D. "Olive, Trickle". Consumable Online. Archived from the original on 31 May 2001. Retrieved 29 August 2006.