Oscan language

Oscan is an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy. The language is in the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic branch of the Italic languages. Oscan is therefore a close relative of Umbrian.

| Oscan | |

|---|---|

Denarius of Marsican Confederation with Oscan legend | |

| Native to | Samnium, Campania, Lucania, Calabria and Abruzzo |

| Region | south and south-central Italy |

| Extinct | >79 CE[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Old Italic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | osc |

osc | |

| Glottolog | osca1244 |

Approximate distribution of languages in Iron Age Italy in the sixth century BCE | |

Oscan was spoken by a number of tribes, including the Samnites,[2] the Aurunci (Ausones), and the Sidicini. The latter two tribes were often grouped under the name "Osci". The Oscan group is part of the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic family, and includes the Oscan language and three variants (Hernican, Marrucinian and Paelignian) known only from inscriptions left by the Hernici, Marrucini and Paeligni, minor tribes of eastern central Italy. Adapted from the Etruscan alphabet, the Central Oscan alphabet was used to write Oscan in Campania and surrounding territories from the 5th century BCE until possibly the 1st century CE.[3]

Evidence

Oscan is known from inscriptions dating as far back as the 5th century BCE. The most important Oscan inscriptions are the Tabula Bantina, the Oscan Tablet or Tabula Osca,[4] and the Cippus Abellanus. In Apulia, there is evidence that ancient currency was inscribed in Oscan (dating to before 300 BCE)[5] at Teanum Apulum.[6] Oscan graffiti on the walls of Pompeii indicate its persistence in at least one urban environment well into the 1st century of the common era.[7]

In total, as of 2017, there were 800 found Oscan texts, with a rapid expansion in recent decades.[8] Oscan was written in various scripts depending on time period and location, including the "native" Oscan script, the South Oscan script which was based on Greek, and the ultimately prevailing Roman Oscan script.[8]

Demise

In coastal zones of Southern Italy, Oscan is thought to have survived three centuries of bilingualism with Greek between 400 and 100 BCE, making it "an unusual case of stable societal bilingualism" wherein neither language became dominant or caused the death of the other; however, over the course of the Roman period, both Oscan and Greek would be progressively effaced from Southern Italy, excepting the controversial possibility of Griko representing a continuation of ancient dialects of Greek.[8] Oscan's usage declined following the Social War.[9] Graffiti in towns across the Oscan speech area indicate it remained in colloquial usage.[1] One piece of evidence that supports the colloquial usage of the language is the presence of Oscan graffiti on walls of Pompeii that were reconstructed after the earthquake of 62 CE,[10][11] which must therefore have been written between 62 and 79 CE.[1] Other scholars argue that this is not strong evidence for the survival of Oscan as an official language in the area, given the disappearance of public inscriptions in Oscan after Roman colonization.[12] It is possible that both languages existed simultaneously under different conditions, in which Latin was given political, religious, and administrative importance while Oscan was considered a "low" language.[13][14] This phenomenon is referred to as diglossia with bilingualism.[15] Some Oscan graffiti exists from the 1st century CE, but it is rare to find evidence from Italy of Latin-speaking Roman citizens representing themselves as having non–Latin-speaking ancestors.[12]

General characteristics

Oscan speakers came into close contact with the Latium population.[16] Early Latin texts have been discovered nearby major Oscan settlements. For example, the Garigliano Bowl was found close to Minturnae, less than 40 kilometers from Capua, which was once a large Oscan settlement.[16] Oscan had much in common with Latin, though there are also many striking differences, and many common word-groups in Latin were absent or represented by entirely different forms. For example, Latin volo, velle, volui, and other such forms from the Proto-Indo-European root *wel- ('to will') were represented by words derived from *gher ('to desire'): Oscan herest ('(s)he shall want, (s)he shall desire', German cognate 'begehren', English cognate 'yearn') as opposed to Latin volent (id.). Latin locus (place) was absent and represented by the hapax slaagid (place), which Italian linguist Alberto Manco has linked to a surviving local toponym.[17]

In phonology too, Oscan exhibited a number of clear differences from Latin: thus, Oscan 'p' in place of Latin 'qu' (Osc. pis, Lat. quis) (compare the similar P-Celtic/Q-Celtic cleavage in the Celtic languages); 'b' in place of Latin 'v'; medial 'f' in contrast to Latin 'b' or 'd' (Osc. mefiai, Lat. mediae).[18]

Oscan is considered to be the most conservative of all the known Italic languages, and among attested Indo-European languages it is rivaled only by Greek in the retention of the inherited vowel system with the diphthongs intact.[19][16]

Writing system

Alphabet

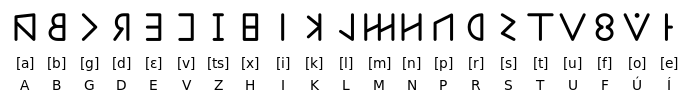

Oscan was originally written in a specific "Oscan alphabet", one of the Old Italic scripts derived from (or cognate with) the Etruscan alphabet. Later inscriptions are written in the Greek and Latin alphabets.[20]

The "Etruscan" alphabet

The Osci probably adopted the archaic Etruscan alphabet during the 7th century BCE, but a recognizably Oscan variant of the alphabet is attested only from the 5th century BCE; its sign inventory extended over the classical Etruscan alphabet by the introduction of lowered variants of I and U, transcribed as Í and Ú. Ú came to be used to represent Oscan /o/, while U was used for /u/ as well as historical long */oː/, which had undergone a sound shift in Oscan to become ~[uː].

The Z of the native alphabet is pronounced [ts].[21] The letters Ú and Í are "differentiations" of U and I, and do not appear in the oldest writings.[21] The Ú represents an o-sound,[18] and Í is a higher-mid [ẹ]. Doubling of vowels was used to denote length but a long I is written IÍ.[18]

The "Greek" alphabet

Oscan written with the Greek alphabet was identical to the standard alphabet with the addition of two letters: one for the native alphabet's H and one for its V.[18] The letters η and ω do not indicate quantity.[18] Sometimes, the clusters ηι and ωϝ denote the diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ respectively while ει and oυ are saved to denote monophthongs /iː/ and /uː/ of the native alphabet.[18] At other times, ει and oυ are used to denote diphthongs, in which case o denotes the /uː/ sound.[18]

The "Latin" alphabet

When written in the Latin alphabet, the Oscan Z does not represent [ts] but instead [z], which is not written differently from [s] in the native alphabet.[20]

Transliteration

When Oscan inscriptions are quoted, it is conventional to transliterate those in the "Oscan" alphabet into Latin boldface, those in the "Latin" alphabet into Latin italics, and those in the "Greek" alphabet into the modern Greek alphabet. Letters of all three alphabets are represented in lower case.[22]

History of sounds

Vowels

Vowels are regularly lengthened before ns and nct (in the latter of which the n is lost) and possibly before nf and nx as well.[23] Anaptyxis, the development of a vowel between a liquid or nasal and another consonant, preceding or following, occurs frequently in Oscan; if the other (non-liquid/nasal) consonant precedes, the new vowel is the same as the preceding vowel. If the other consonant follows, the new vowel is the same as the following vowel.[24]

A

Short a remains in most positions[25] Long ā remains in an initial or medial position. Final ā starts to sound similar to [ɔː] so that it is written ú or, rarely, u.[26]

E

Short e "generally remains unchanged;" before a labial in a medial syllable, it becomes u or i, and before another vowel, e raises to higher-mid [ẹ], written í.[27] Long ē similarly raises to higher-mid [ẹ], the sound of written í or íí.[28]

I

Short i becomes written í.[29] Long ī is spelt with i but when written with doubling as a mark of length with ií.[30]

O

Short o remains mostly unchanged, written ú;[31] before a final -m, o becomes more like u.[32] Long ō becomes denoted by u or uu.[33]

U

Short u generally remains unchanged; after t, d, n, the sound becomes that of iu.[34] Long ū generally remains unchanged; it changed to an ī sound in monosyllables, and may have changed to an ī sound for final syllables.[35]

Diphthongs

The sounds of diphthongs remain unchanged.[19]

S

In Oscan, s between vowels did not undergo rhotacism as it did in Latin and Umbrian; but it was voiced, becoming the sound /z/. However, between vowels, the original cluster rs developed either to a simple r with lengthening on the preceding vowel, or to a long rr (as in Latin), and at the end of a word, original rs becomes r just as in Latin. Unlike in Latin, the s is not dropped, either Oscan or Umbrian, from the consonant clusters sm, sn, sl: Umbrian `sesna "dinner," Oscan kersnu vs Latin cēna.[36]

Examples of Oscan texts

From the Cippus Abellanus

Ekkum svaí píd herieset trííbarak avúm tereí púd liímítúm pernúm púís herekleís fíísnú mefiú íst, ehtrad feíhúss pús herekleís fíísnam amfret, pert víam pússt íst paí íp íst, pústin slagím senateís suveís tanginúd tríbarakavúm líkítud. íním íúk tríbarakkiuf pam núvlanús tríbarakattuset íúk tríbarakkiuf íním úíttiuf abellanúm estud. avt púst feíhúís pús físnam amfret, eíseí tereí nep abellanús nep núvlanús pídum tríbarakattíns. avt thesavrúm púd eseí tereí íst, pún patensíns, múíníkad tanginúd patensíns, íním píd eíseí thesavreí púkkapíd eestit aíttíúm alttram alttrús herríns. avt anter slagím abellanam íním núvlanam súllad víú uruvú íst. pedú íst eísaí víaí mefiaí teremenniú staíet.

In Latin:

Item si quid volent aedificare in territorio quod limitibus tenus quibus Herculis fanum medium est, extra muros, qui Herculis fanum ambiunt, [per] viam positum est, quae ibi est, pro finibus senatus sui sententia, aedificare liceto. Et id aedificium quam Nolani aedificaverint, id aedificium et usus Abellanorum esto. At post muros qui fanum ambiunt, in eo territorio nec Avellani nec Nolani quidquam aedificaverint. At thesaurum qui in eo territorio est, cum paterent, communi sententia paterent, et quidquid in eo thesauro quandoque extat, portionum alteram alteri caperent. At inter fines Abellanos et Nolanos ubique via curva est, [pedes] est in ea via media termina stant.

In English:

And if anyone shall want to build on the land within the boundaries where the temple of Hercules stands in the middle, may the senate allow him to build outside of the walls that encircle the sanctuary of Hercules, across the road leads there. And a building that a man from Nola builds, shall be of use by the people of Nola. And a building that a man from Abella builds, shall be of use by the people of Abella. But beyond the wall that encircle the sanctuary, in that territory neither the Abellans nor the Nolans may build anything. But the treasury that is in that territory, when it is opened it shall be opened following a shared decision, and whatever is in that treasury, they shall share equally amongst them. But the road that as between the borders of Abella and Nola is a communal road. The boundaries stand in the middle of this road.

First paragraph

out of six paragraphs in total, lines 3-8 (the first couple lines are too damaged to be clearly legible):

(3) … deiuast maimas carneis senateis tanginud am … (4) XL osiins, pon ioc egmo comparascuster. Suae pis pertemust, pruter pan … (5) deiuatud sipus comenei, perum dolum malum, siom ioc comono mais egmas touti- (6)cas amnud pan pieisum brateis auti cadeis amnud; inim idic siom dat senates (7) tanginud maimas carneis pertumum. Piei ex comono pertemest, izic eizeic zicelei (8) comono ni hipid.[37]

In Latin:

(3) … iurabit maximae partis senatus sententia [dummodo non minus] (4) XL adsint, cum ea res consulta erit. Si quis peremerit, prius quam peremerit, (5) iurato sciens in committio sine dolo malo, se ea comitia magis rei publicae causa, (6) quam cuiuspiam gratiae aut inimicitiae causa; idque se de senatus (7) sententia maximae partis perimere. Cui sic comitia perimet (quisquam), is eo die (8) comitia non habuerit.[37]

In English:

(3) … he shall take oath with the assent of the majority of the senate, provided that not less than (4) 40 are present, when the matter is under advisement. If anyone by right of intercession shall prevent the assembly, before preventing it, (5) he shall swear wittingly in the assembly without guile, that he prevents this assembly rather for the sake of the public welfare, (6) rather than out of favor or malice toward anyone; and that too in accordance with the judgment of the majority of the senate. The presiding magistrate whose assembly is prevented in this way shall not hold the assembly on this day.[38]

Notes: Oscan carn- “part, piece” is related to Latin carn- “meat” (seen in English ‘carnivore’), from an Indo-European root *ker- meaning ‘cut’―apparently the Latin word originally meant ‘piece (of meat).’[39] Oscan tangin- "judgement, assent" is ultimately related to English 'think'. [40]

Second paragraph

= lines 8-13. In this and the following paragraph, the assembly is being discussed in its judiciary function as a court of appeals:

(8) ...Pis pocapit post post exac comono hafies meddis dat castris loufir (9) en eituas, factud pous touto deiuatuns tanginom deicans, siom dateizasc idic tangineis (10) deicum, pod walaemom touticom tadait ezum. nep fefacid pod pis dat eizac egmad min[s] (11) deiuaid dolud malud. Suae pis contrud exeic fefacust auti comono hipust, molto etan- (12) -to estud: n.

. In. suaepis ionc fortis meddis moltaum herest, ampert minstreis aeteis (13) aetuas moltas moltaum licitud.[41]

In Latin:

(8) ...Quis quandoque post hac comitia habebit magistratus de capite (9) vel in pecunias, facito ut populus iuras sententiam dicant, se de iis id sententiae (10) deicum, quod optimum populum censeat esse, neve fecerit quo quis de ea re minus (11) iuret dolo malo. Si quis contra hoc fecerit aut comitia habuerit, multo tanta esto: n. MM. Et siquis eum potius magistratus multare volet, dumtaxat minoris partis (13) pecuniae multae multare liceto.[41]

In English:

(8) ... Whatever magistrate shall hereafter hold an assembly in suit involving the death penalty (9) or a fine, let him make the people pronounce judgment, after having sworn that they will such judgment (10) render, as they believe to be for the best public good, and let him prevent anyone from, in this matter, (11) swearing with guile. If anyone shall act or hold a council contrary to this, let the fine be 2000 sesterces. And if any magistrate prefers to fix the fine, he may do so, provided it is less than half the property (13) of the guilty person.[42]

Third Paragraph

= lines 13-18

(13)...Suaepis pru meddixud altrei castrud auti eituas (14) zicolom dicust, izic comono ni hipid ne pon op toutad petirupert ururst sipus perum dolom (15) mallom in. trutum zico. touto peremust. Petiropert, neip mais pomptis, com preiuatud actud (16) pruter pam medicationom didest, in.pon posmom con preiuatud urust, eisucen zuculud (17) zicolom XXX nesimum comonom ni hipid. suae pid contrud exeic fefacust, ionc suaepist (18) herest licitud, ampert mistreis aeteis eituas[43]

In Latin:

(13)... Siquis pro matistatu alteri capitis aut pecuniae (14) diem dixerit, is comitia ne habuerit nisi cum apud populum quater oraverit sciens sine dolo (15) malo et quartum diem populus perceperit. Quater, neque plus quinquens, reo agito (16) prius quam iudicationem dabit, et cum postremum cum reo oraverit, ab eo die (17) in diebus XXX proximis comitia non habuerit. Si quis contra hoc fecerit, eum siquis volet magistratus moltare, (18) liceto, dumtaxat minoris partis pecuniae liceto.[43]

In English:

(13) ...If any magistrate, in a suit involving a death or a fine for another, (14) shall have appointed the day, he must not hold the assembly until he has brought the accusation four times in the presence of the people without (15) guile, and the people have been advised of the fourth day. Four times, and not more than five, must he must he argue the case with the defendant before he pronounces the indictment, and when he has argued for the last time with the defendant, he must not hold the assembly within thirty days from that day. And if anyone shall have done contrary to this, if any magistrate wishes to fix the fine, (18) he may, but only for less than half the property of the guilty person be permitted.[44]

The Testament of Vibius Adiranus

In Oscan:

v(iíbis). aadirans. v(iíbieís). eítiuvam. paam vereiiaí. púmpaiianaí. trístaamentud. deded. eísak. eítiuvad v(iíbis). viínikiís. m(a)r(aheis). kvaísstur. púmpaiians. trííbúm. ekak. kúmbennieís. tanginud. úpsannam deded. ísídum. prúfatted.[12]

In English:

Vibius Adiranus, son of Vibius, gave in his will money to the Pompeian vereiia-. With this money, Vibius Vinicius, son of Maras, Pompeian quaestor, dedicated the construction of this building by decision of the senate, and the same man approved it.[12]

See also

References

- Schrijver, Peter (2016). "Oscan love of Rome". Glotta. 92 (1): 223–226. doi:10.13109/glot.2016.92.1.223. ISSN 0017-1298. Page 2 in the online version.

- Monaco, Davide (4 November 2011). "Samnites the People". Samniti.info. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Lejeune, Michel (1970). "Phonologie osque et graphie grecque". Revue des Études Anciennes (in French). 72 (3): 271–316. doi:10.3406/rea.1970.3871. ISSN 0035-2004.

- "Samnites Oscan Tablet of Agnone".

- "Teano Apulo". Treccani (in Italian).

- Salvemini Biagio, Massafra Angelo (May 2014). Storia della Puglia. Dalle origini al Seicento (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 978-88-581-1388-2.

- Freeman, Philip (1999). The Survival of Etruscan. Page 82: "Oscan graffiti on the walls of Pompeii show that non-Latin languages could thrive in urban locations in Italy well into the 1st century CE."

- McDonald, K. L. (2017). "Fragmentary ancient languages as "bad data": towards a methodology for investigating multilingualism in epigraphic sources" (PDF). pp. 4–6.

- Lomas, Kathryn, "The Hellenization of Italy", in Powell, Anton. The Greek World. Page 354.

- Cooley, Alison (2002)."The survival of Oscan in Roman Pompeii", in A.E. Cooley (ed.), Becoming Roman, Writing Latin? Literacy and Epigraphy in the Roman West, Portsmouth (Journal of Roman Archaeology), 77–86. Page 84

- Cooley (2014). Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. New York – London (Routledge). Page 104.

- McDonald, Katherine (2012). "The Testament of Vibius Adiranus". Journal of Roman Studies. 102: 40–55. doi:10.1017/S0075435812000044. ISSN 0075-4358. S2CID 162821087.

- Cooley, Alison; Burnett, Andrew M. (2002). Becoming Roman, writing Latin? : literacy and epigraphy in the Roman West. Journal of Roman Archaeology. ISBN 1-887829-48-2. OCLC 54951998.

- Vaänänen, Veikko (31 December 1959). Le latin vulgaire des inscriptions pompéiennes. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783112537206. ISBN 978-3-11-253720-6. S2CID 246734111.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (27 August 2003), "Bilingualism with and without diglossia; diglossia with and without bilingualism", The Bilingualism Reader, Routledge, pp. 87–94, doi:10.4324/9780203461341-12, ISBN 978-0-203-46134-1, retrieved 9 April 2022

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey C. (2011). The Blackwell history of the Latin language. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3920-8. OCLC 126227889.

- Alberto Manco, "Sull’osco *slagi-", AIΩN Linguistica 28, 2006.

- Buck 1904, p. 23.

- Buck 1904, p. 18.

- Buck 1904, pp. 22–23.

- Buck 1904, p. 22.

- Buck 1904, p. xvii.

- Buck 1904, p. 47.

- Buck 1904, p. 50.

- Buck 1904, pp. 29–30.

- Buck 1904, p. 30.

- Buck 1904, pp. 31–32.

- Buck 1904, p. 33.

- Buck 1904, p. 34.

- Buck 1904, p. 35.

- Buck 1904, p. 36.

- Buck 1904, p. 37.

- Buck 1904, p. 38.

- Buck 1904, p. 40.

- Buck 1904, p. 41.

- Buck 1904, pp. 73–76.

- Buck 1904, p. 231.

- Buck 1904, p. 235.

- "Etymonline: Proto-Indo-European *sker-".

- "Etymonline: think".

- Buck 1904, pp. 231–232.

- Buck 1904, pp. 236.

- Buck 1904, pp. 232.

- Buck 1904, pp. 237.

Sources

- Buck, Carl Darling (1904). A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: with a Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Boston: Ginn & Company. OCLC 1045590290.

- Salvucci, Claudio R. (1999). A Vocabulary of Oscan Including the Oscan and Samnite Glosses. Southampton, Pennsylvania: Evolution Publishing and Manufacturing Co.

Further reading

Linguistic Outlines:

- Prosdocimi, A.L. 1978. «L’osco». In Lingue e dialetti dell’Italia antica, a cura di Aldo Luigi Prosdocimi, 825–912. Popoli e civiltà dell’Italia antica 6. Roma - Padova: Biblioteca di storia patria.

Studies:

- Planta, R. von 1892-1897. Grammatik der oskisch-umbrischen Dialekte. 2 voll. Strassburg: K. J. Trubner. Vol. 1; Vol. 2

- Conway, Robert Seymour 1897. The Italic Dialects: Edited with a Grammar and Glossary. 2 voll. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Vol. 1; Vol. 2

- Cooley, Alison E. 2002. "The survival of Oscan in Roman Pompeii." Becoming Roman, writing Latin? : literacy and epigraphy in the Roman West. Journal of Roman Archaeology. ISBN 1-887829-48-2. OCLC 54951998.

- Fishman, J.A. 1967. "Bilingualism with and without diglossia; diglossia with and without bilingualism." Journal of Social Issues 23, 29-38.

- Pisani, Vittore. 1964. Le lingue dell'Italia antica oltre il Latino. Rosenberg & Sellier. ISBN 978-88-7011-024-1

- Lejeune, Michel. "Phonologie osque et graphie grecque". In: Revue des Études Anciennes. Tome 72, 1970, n°3-4. pp. 271–316. doi:10.3406/rea.1970.3871

- Untermann, J. 2000. Wörterbuch des Oskisch-Umbrischen. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

- McDonald, Katherine. 2015. Oscan in Southern Italy and Sicily: Evaluating Language Contact in a Fragmentary Corpus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316218457.

- Zair, Nicholas (2016). Oscan In The Greek Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107706422. ISBN 978-1-107-70642-2.

- Machajdíková, Barbora; Martzloff, Vincent. "Le pronom indéfini osque pitpit "quicquid" de Paul Diacre à Jacob Balde: morphosyntaxe comparée des paradigmes *kwi- kwi- du latin et du sabellique". In: Graeco-Latina Brunensia. 2016, vol. 21, iss. 1, pp. 73-118. ISSN 2336-4424. doi:10.5817/GLB2016-1-5

- Petrocchi, A., Wallace, R. 2019. Grammatica delle Lingue Sabelliche dell’Italia Antica. München: LINCOM GmbH. [ed. inglese. 2007]

Texts

- Janssen, H.H. 1949. Oscan and Umbrian Inscriptions, Leiden.

- Vetter, E. 1953. Handbuch der italischen Dialekte, Heidelberg.

- Rix, H. 2002. Sabellische Texte. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

- Crawford, M. H. et al. 2011. Imagines Italicae. London: Institute of Classical Studies.

- Franchi De Bellis, A. 1988. Il cippo abellano. Universita Degli Studi Di Urbino.

- Del Tutto Palma, Loretta. 1983. La Tavola Bantina (sezione osca): Proposte di rilettura. Vol. 1. Linguistica, epigrafia, filologia italica, Quaderni di lavoro.

- Del Tutto Palma, L. (a cura di) 1996. La tavola di Agnone nel contesto italico. Atti del Convegno di studio (Agnone 13-15 aprile 1994). Firenze: Olschki.

- Franchi De Bellis, Annalisa. 1981. Le iovile capuane. Firenze: L.S. Olschki.

- Murano, Francesca. 2013. Le tabellae defixionum osche. Pisa ; Roma: Serra.

- Decorte, Robrecht. 2016. "Sine dolo malo: The Influence and Impact of Latin Legalese on the Oscan Law of the Tabula Bantina". Mnemosyne 69 (2): 276–91.

External links

| Library resources about Oscan language |

- "Languages and Cultures of Ancient Italy. Historical Linguistics and Digital Models", Project fund by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (P.R.I.N. 2017)

- Hare, JB (2005). "Oscan". wordgumbo. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Gipert, Jost (2001). "Oscan". TITUS DIDACTICA. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- Image of Tabula Batina