Lycian language

The Lycian language (𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊍𐊆 Trm̃mili)[2] was the language of the ancient Lycians who occupied the Anatolian region known during the Iron Age as Lycia. Most texts date back to the fifth and fourth century BC. Two languages are known as Lycian: regular Lycian or Lycian A, and Lycian B or Milyan. Lycian became extinct around the beginning of the first century BC, replaced by the Ancient Greek language during the Hellenization of Anatolia. Lycian had its own alphabet, which was closely related to the Greek alphabet but included at least one character borrowed from Carian as well as characters proper to the language. The words were often separated by two points.

| Lycian | |

|---|---|

| 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊍𐊆 Trm̃mili | |

Xanthos stele with Lycian inscriptions | |

| Native to | Lycia, Lycaonia |

| Region | Southwestern Anatolia |

| Ethnicity | Lycians |

| Era | 500 – ca. 200 BC[1] |

Early forms | |

| Lycian script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xlc |

xlc | |

| Glottolog | lyci1241 |

Area

Lycia covered the region lying between the modern cities of Antalya and Fethiye in southern Turkey, especially the mountainous headland between Fethiye Bay and the Gulf of Antalya. The Lukka, as they were referred to in ancient Egyptian sources, which mention them among the Sea Peoples, probably also inhabited the region called Lycaonia, located along the next headland to the east, also mountainous, between the modern cities of Antalya and Mersin.

Discovery and decipherment

From the late eighteenth century Western European travellers began to visit Asia Minor to deepen their acquaintance with the worlds of Homer and the New Testament. In southwest Asia Minor (Lycia) they discovered inscriptions in an unknown script. The first four texts were published in 1820, and within months French Orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin used a bilingual showing individuals' names in Greek and Lycian as a key to transliterate the Lycian alphabet and determine the meaning of a few words.[4] During the next century the number of texts increased, especially from the 1880s when Austrian expeditions systematically combed through the region. However, attempts to translate any but the most simple texts had to remain speculative, although combinatorial analysis of the texts cleared up some grammatical aspects of the language. The only substantial text with a Greek counterpart, the Xanthos stele, was hardly helpful because the Lycian text was quite heavily damaged, and worse, its Greek text does not anywhere come near to a close parallel.[5]

It was only after the decipherment of Hittite, by Bedřich Hrozný in 1917, that a language became known that was closely related to Lycian and could help etymological interpretations of the Lycian vocabulary. A next leap forward could be made with the discovery in 1973 of the Letoon trilingual in Lycian, Greek and Aramaic.[6] Though much remains unclear, comprehensive dictionaries of Lycian have been composed since by Craig Melchert[7] and Günter Neumann.[8]

Sources

Lycian is known from these sources, some of them fairly extensive:[9][10][11]

- 172 inscriptions on stone in the Lycian script dating from the 5th and 4th century BC (until ca. 330 BC).[12] They include:

- The Xanthus stele. The inscribed upper part of a tomb at Xanthos, called the Xanthus Stele or the Xanthus Obelisk. A Lycian A inscription covers the south, east and part of the north faces. The north side also contains a 12 line poem in Greek and additional text, found mainly on the west side, in Milyan. Milyan appears only there and on a tomb in Antiphellos. The total number of lines on the stele is 255, including 138 in Lycian A, 12 in Greek, and 105 in Milyan.

- The Letoon trilingual, in Lycian A, Greek and Aramaic.

- 150 burial instructions carved on rock tombs.

- 20 votive or dedicatory inscriptions.

- About 100 inscriptions on coins minted at Xanthus from the reign of Kuprili, 485-440 BC, to the reign of Pericle, 380-360 BC.[13]

- Personal and place names in Greek.

Lycian alphabet

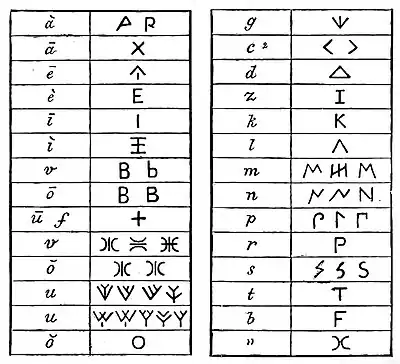

The Lycian alphabet consists of about 29 signs, many of them reminiscent of the Greek alphabet:

| Lycian sign | 𐊀 | 𐊂 | 𐊄 | 𐊅 | 𐊆 | 𐊇 | 𐊈 | 𐊛 | 𐊉 | 𐊊 | 𐊋 | 𐊍 | 𐊎 | 𐊏 | 𐊒 | 𐊓 | 𐊔 | 𐊕 | 𐊖 | 𐊗 | 𐊁 | 𐊙 | 𐊚 | 𐊐 | 𐊑 | 𐊘 | 𐊌 | 𐊃 | 𐊜 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| transcription | a | b | g | d | i | w | z | h | θ | j (y) | k | l | m | n | u | p | κ (c) | r | s | t | e | ã | ẽ | m̃ | ñ | τ | q | β | χ |

| pronounced (IPA) | /a/ | /β/ | /ɣ/ | /ð/ | /i/, /ĩ/ | /w/ | /t͡s/ | /h/ | /θ/ | /j/ | /kʲ/, /ɡʲ/ | /l/, /l̩~əl/ | /m/ | /n/ | /u/, /ũ/ | /p/, /b/ | /k/?, /kʲ/?, /h(e)/? | /r/, /r̩~ər/ | /s/ | /t/ | /e/ | /ã/ | /ẽ/ | /m̩/, /əm/, /m./ | /n̩/, /ən/, /n./ | /tʷ/? /t͡ʃ/? | /k/, /g/ | /k/? /kʷ/? | /q/ |

| Greek equivalent | Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | Ϝ | Ζ | Η | Θ | Ι | Κ | Λ | Μ | Ν | Ο | Π | Ϙ | Ρ | Σ | Τ | Ψ |

Classification

Lycian was an Indo-European language, one in the Luwian subgroup of Anatolian languages. A number of principal features help identify Lycian as being in the Luwian group:[14]

- Assibilation of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) palatals (satem change): *h₁éḱwos to Luwian á-zú-wa/i-, Lycian esbe 'horse'.

- Replacement of genitive case with adjectives ending in -ahi or -ehi, Luwian -assi-.

- A preterite active formed with PIE secondary middle endings:

- PIE *-to to Luwian -ta, Lycian -te or -de in the third person singular

- PIE *-nto to Luwian -nta, Lycian -(n)te in the third person plural

- Similarity of words: Luwian māssan(i)-, Lycian māhān(i) 'god'.

The Luwian subgroup also includes cuneiform and hieroglyphic Luwian, Carian, Sidetic, Milyan and Pisidic.[15] The pre-alphabetic forms of Luwian extended back into the Late Bronze Age and preceded the fall of the Hittite Empire. These vanished at about the time of the Neo-Hittite states in southern Anatolia (and Syria); thus, the Iron Age members of the subgroup are localized daughter languages of Luwian.

Of the Luwic languages, only the Luwian parent language is attested prior to 1000 BC, so it is unknown when the classical-era dialects diverged. Whether the Lukka people always resided in southern Anatolia or whether they always spoke Luwian are different topics.

From the inscriptions, scholars have identified at least two languages that were termed Lycian. One is considered standard Lycian, also termed Lycian A; the other, which is attested on side D of the Xanthos stele, is Milyan or Lycian B, separated by its grammatical particularities.

Grammar

Nouns

Nouns and adjectives distinguish singular and plural forms. A dual has not been found in Lycian. There are two genders: animate (or 'common') and inanimate (or 'neuter'). Instead of the genitive singular case normally a so-called possessive (or "genitival adjective") is used, as is common practice in the Luwic languages: a suffix -(e)h- is added to the root of a substantive, and thus an adjective is formed that is declined in turn.

Nouns can be divided in five declension groups: a-stems, e-stems, i-stems, consonant stems, and mixed stems; the differences between the groups are very minor. The declension of nouns goes as follows:[16][17][18]

| case | ending | lada 'wife, lady' | tideimi 'son, child' | tuhes 'nephew, niece' | tese 'vow, oath' | atlahi 'own' | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| animate | inanimate | (a-stem) | (i/e-stem) | (consonant stem) | (inanimate) | (adjective)[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Singular | Nominative | -Ø, -s | -~, -Ø, -yẽ | lada | tideimi | tuhes | (tese) | atlahi |

| Accusative | -~, -u, -ñ | ladã, ladu | tideimi | tuhesñ | atlahi | |||

| Ergative | — | ? | ||||||

| Dative | -i | ladi | tideimi | tuhesi | atlahi | |||

| Locative | -a, -e, -i | (lada) | (tideime) | tesi | (atlahi) | |||

| Genitive | -Ø, -h(e); Possessive: -(e)he-, -(e)hi- | (Poss.:) laθθi | ||||||

| SIng., Pl. | Ablative-instrumental | -di | (ladadi) | (tideimedi) | tuhedi | |||

| Plural | Nominative | ~-i | -a | ladãi | tideimi | tuhẽi | tasa | |

| Accusative | -s | ladas | tideimis | |||||

| Ergative | — | -ẽti | tesẽti, teseti | |||||

| Dative/Locative | -e, -a | lada | tideime | tuhe | tese | atlahe | ||

| Genitive | -ẽ, -ãi | ladãi (?) | tideimẽ | |||||

- atlahi is the possessive derivative of atla, 'person'.

Demonstrative pronoun

The paradigm for the demonstrative pronoun ebe, "this" is:[19][18]

| case | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| animate | inanimate | animate | inanimate | |

| Nominative | ebe | ebẽ | ebẽi | ebeija |

| Accusative | ebẽ, ebeñnẽ, ebẽñni | ebeis, ebeijes | ||

| Dative / Locative | ebehi | ebette | ||

| Genitive | (Possessive:) ebehi | ebẽhẽ | ||

| Ablative / Instrumental | ? | ? | ||

Personal pronoun

The demonstrative ebe, 'this', is also used as a personal pronoun: 'this one', therefore 'he, she, it'. Here is a paradigm of all attested personal pronouns:[18]

| case | ẽmu, amu 'I' |

ẽmi- 'my' |

eb(e)- 'he, she, it' |

ehbi(je)- 'his' |

epttehe/i-, eb(e)ttehe/i- 'their' | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| animate | inanimate | animate | inanimate | |||||

| Singular | Nominative | ẽmu, amu | ẽmi | ebe | ehbi | ehbijẽ | ebttehi | |

| Accusative | ebñnẽ | |||||||

| Genitive | (Possessive:) ehbijehi | |||||||

| Dative | emu | ehbi | ebttehi | |||||

| Ablative/Instrumental | ehbijedi | |||||||

| Plural | Nominative | ehbi | ehbija | ebttehi | ||||

| Accusative | ẽmis | ehbis | ebttehis | |||||

| Genitive | ||||||||

| Dative / Locative | ebtte | ehbije | epttehe | |||||

Other pronouns

Other pronouns are:[18]

- Relative or interrogative pronouns: ti-, 'who, which'; teri or ẽke, 'when'; teli, 'where'; km̃mẽt(i)-, 'how many' (also indefinite: 'however many').

- Indefinite pronouns: tike-, 'someone, something'; tise, 'anyone, anything'; tihe, 'any'.

Numerals

The following numerals are attested:[18]

| cardinal number | 'x-fold' | 'x-year-old' | also attested | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| two | [kbi-] | tupm̃me-, 'twofold, pair' | kbisñne/i-, 'two-year-old' | kbihu, 'twice'; kbijẽt(i)-, 'double'; kbi-, kbije-, '(an-)other'; kbisñtãta, 'twenty' |

| three | teri- | trppem-, 'threefold (?)' | trisñne/i-, 'three-year-old' | (Milyan:) trisu, 'thrice' |

| four | mupm̃m[- | mupm̃m[-, 'four, fourfold' | ||

| eight | aitãta | |||

| nine | nuñtãta | |||

| twelve | qñnãkba | (Milyan:) qñnãtbisu, 'twelve times' | ||

| twenty | kbisñtãta |

Verbs

Just as in other Anatolian languages (Luwian, Lydian) verbs in Lycian were conjugated in the present-future and preterite tenses and in the imperative with three persons singular and plural. Some endings have many variants, due to nasalization (-a- → -añ-, -ã-; -e- → -eñ-, -ẽ-), lenition (-t- → -d-), gemination (-t- → -tt-; -d- → -dd-), and vowel harmonization (-a- → -e-: prñnawãtẽ → prñnewãtẽ).

About a dozen conjugations can be distinguished, on the basis of (1) the verbal root ending (a-stems, consonant stems, -ije-stems, etc.), and (2) the endings of the third person singular being either unlenited (present -ti; preterite -te; imperative -tu) or lenited (-di; -de; -du). For example, prñnawa-(ti) (to build) is an unlenited a-stem (prñnawati, he builds), a(i)-(di) (to make) is a lenited a(i)-stem (adi, he makes). Differences between the various conjugations are minor.

Verbs are conjugated as follows; Mediopassive (MP) forms are in brown:[20][21]

| Active | Mediopassive | prñnawa-(ti) | (t)ta-(di) | a(i)-(di) | (h)ha-(ti) | si-(?) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ending | ending | 'to build' | 'to put, place' | 'to make, do' | 'to release' | 'to lie' (MP) | |||

| Present / future | Singular | 1 | -u (-w) | -xani, -xãni | sixani | ||||

| 2 | ? | ? | |||||||

| 3 | -di, -(t)ti, -i, -e | -ẽni, -tẽni | prñnawati | (t)tadi | adi, edi | hadi, hati | sijẽni, sijeni, sitẽni | ||

| Plural | 1 | ? | ? | ||||||

| 2 | (-tẽni ?) | ? | |||||||

| 3 | ~-ti, -(i)ti, -ñti | ~-tẽni (?) | tãti (tẽti) | aiti | (h)hãti, (h)hati | sitẽni (?) | |||

| Preterite | Singular | 1 | -(x)xa, -xã, -ga, -ax(a) | -xagã, -xaga (?) | prñnawaxã, -waxa | taxa | axa, aga, axã, agã; (MP:) axagã, axaga | ||

| 3 | -tẽ, -(t)te, -dẽ, -de | (-tte ?) | prñnawatẽ, -wate (-wetẽ, -wete) | tadẽ, tade (tetẽ ?) | adẽ. ade (ede, ada) | hadẽ, hade | |||

| Plural | 1 | ? | ? | ||||||

| 3 | ~-tẽ, -(i)tẽ, -(i)te, ~-te, -ñtẽ, -ñte | ? | prñnawãtẽ, -wãte; prñnewãtẽ | tete | aitẽ, aite | hãtẽ, hãte | |||

| Imperative | Singular | 1 | -lu (?)[22] | ? | |||||

| 2 | -Ø[22] | ? | |||||||

| 3 | -(t)tu, -du, -u | (-tẽnu ?) | tatu | hadu | |||||

| Plural | 2 | (-tẽnu ?) | (-tẽnu ?) | ||||||

| 3 | ~-tu | (~-tẽnu ?) | tãtu, tatu | ||||||

| Participle Active (Passive?) | Singular | -mi, ~-mi, -me, -ma | |||||||

| Plural | -mi | (acc. neutr.:) eim̃ | (accusative:) hm̃mis | ||||||

| Infinitive | -ne, ~-ne, -na, ~-na | ? | (t)tãne, tane, ttãna | hane, hãne, hhãna | |||||

A suffix -s- (cognate with Greek, Latin -/sk/-), appended to the stem and attested with half a dozen verbs, is thought to make a verb iterative:[18][23]

- stem a(i)-, 'to do, to make', s-stem as-; (Preterite 3 Singular:) ade, adẽ, 'he did, made', astte, 'he always did, has made repeatedly';

- stem tuwe-, 'to erect, place (upright)', s-stem tus-; (Present/future 3 Plural:) tuwẽti, 'they erect', tusñti , 'they will erect repeatedly'.

Syntax

Emmanuel Laroche, who analysed the Lycian text of the Letoon trilingual,[24] concluded that word order in Lycian is slightly more free than in the other Anatolian languages. Sentences in plain text mostly have the structure

- ipc (initial particle cluster) - V (Verb) - S (Subject) - O (direct Object).

The verb immediately follows an "initial particle cluster", consisting of a more or less meaningless particle "se-" or "me-" (literally, 'and') followed by a series of up to three suffixes, often called emphatics. The function of some of these suffixes is mysterious, but others have been identified as pronomina like "he", "it", or "them". The subject, direct object, or indirect object of the sentence may thus proleptically be referred to in the initial particle cluster. As an example, the sentence "X built a house" might in Lycian be structured: "and-he-it / he-built / X / a-house".

Other constituents of a sentence, like an indirect object, predicate, or complimentary adjuncts, can be placed anywhere after the verb.

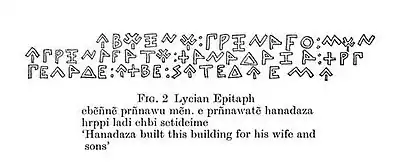

Contrary to this pattern, funeral inscriptions as a rule have a standard form with the object at the head of the sentence: "This tomb built X"; literally: "This tomb / it / he built / X" (order: O - ipc - V - S). Laroche suspects the reason for this deviation to be that in this way emphasis fell on the funerary object: "This object, it was built by X". Example:[25]

1. ebẽñnẽ prñnawã mẽti prñnawatẽ This building, [it was] he who built it: 2. xisteriya xzzbãzeh tideimi Qisteria, Qtsbatse's son, 3. hrppi ladi ehbi se tideime for his wife and for the sons.

In line 1 mẽti = m-ẽ-ti is the initial particle cluster, where m- = me- is the neutral "steppingstone" to which two suffixes are affixed: -ẽ- = "it", and the relative pronoun -ti, "who, he who".

Subject-verb-object hypothesis

Kim McCone proposed in the 1970s that Lycian's unmarked word order was instead subject-verb-object. The apparent VSO and OVS orders come from various frontings and dislocations of a basic SVO structure.

Lycian's SVO is itself a shift from the typical Anatolian subject-object-verb order, of which Lycian preverbal object pronouns like ẽ "him/her/it" would be a relic.[26]

mexisttẽn

Megasthenes.NOM

ẽ-ep[i]tuwe-te

it-set.up.PRET-3sg

Megasthenes set it up…

In spite of McCone's alternative analysis, the assumption that verb-subject-object was Lycian's unmarked word order went unchallenged until the 2010s, when Alwin Kloekhorst independently formulated and adopted the SVO hypothesis. This led to other linguists like Heiner Eichner and H. Craig Melchert to adopt the SVO hypothesis after him.[27] The principal unmarked example cited by SVO supporters comes from the following sentence:[28]

pajawa

Pajawa.NOM

m[a]n[ax]ine:

Manaxine

prñnawa-te:

build.PRET-3sg

prñnaw-ã

building-ACC

ebẽ-ñnẽ:

this-ACC

Pajawa Manaxine built this building. (Note the absence of the initial particle cluster.)

Further examples of subject-initial unmarked clauses cited by Melchert include:[27]

tebursseli

Tebursseli.NOM

prñnawa-te

build.PRET-3sg

lusñ[tr]e

Lysander.GEN

ẽti

at

waziss-e

leadership-LOC

Tebursseli built (this tomb) under Lysander's leadership.[29]

upazij

Upazij.NOM

ẽne-prñnawa-te

it-build.PRET-3sg

hrppi

for

prñnezi

household

ehbi

his.DAT

Upazij built it for his household.[30]

Endonym

"Hanadaza built this building for his wife and sons."

A few etymological studies of the Lycian language endonym are present. These are:[2]

- Language of the mountain people (Laroche): Luwian tarmi- "pointed object" becomes a hypothetical *tarmašši- "mountainous" used in Trm̃mis- "Lycia." Lycia and Pisidia each had a hill-town named Termessos.

- Attarima (Carruba): A previously unknown Late Bronze Age place name among the Lukka.

- Termilae (Bryce): A people displaced from Crete about 1600 BC.

- Termera (Strabo[31]): A Lelege people displaced by the Trojan War, first settling in Caria and assigning such names as Telmessos, Termera, Termerion, Termeros, Termilae, then displaced to Lycia by the Ionians.[32]

See also

References

- Lycian at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- Bryce (1986) page 30.

- Schürr, Diether. "Der lykische Dynast Arttumbara und seine Anhänger". Akademie Verlag. Retrieved 2021-04-07. = Klio 94/1 (2012) 18-44.

- Saint-Martin (1821). "Observations sur les inscriptions lyciennes découvertes par M. Cockerell". Journal des Savans (Avril): 235–248. Retrieved 2021-04-06. (archived at BnF Gallica).

- Neumann, Günther (1969), "Lydisch". In: Handbuch der Orientalistik, II. Band, 1. und 2. Abschnitt, Lieferung 2, Altkleinasiatische Sprachen, Leiden/Köln: Brill, pp. 358-396: pp. 360-371.

- Laroche, Emmanuel (1979). "L'inscription lycienne". Fouilles de Xanthos. VI: 51-128.

- Melchert, H. Craig (2004). A Dictionary of the Lycian Language. Ann Arbor: Beech Stave.

- Neumann, Günter & Tischler, Johann (2007). Glossar des lykischen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Adiego (2007) page 764.

- Bryce (1986) page 42.

- Christiansen, Birgit (2019), Editions of Lycian Inscriptions not Included in Melchert’s Corpus from 2001, in: Adiego (et al., eds.), Ignasi-Xavier (2019). Luwic dialects and Anatolian. Inheritance and diffusion (PDF). Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. pp. 65–134. ISBN 978-84-9168-414-5. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- Bryce (1986) pp. 50, 54.

- Bryce (1986) pages 51–52.

- Adiego (2007) page 765.

- Adiego (2007) page 763.

- Laroche, Emmanuel (1979). "L'inscription lycienne". Fouilles de Xanthos. VI: 51-128: 87, 119–122.

- Kloekhorst, Alwin (2013). "Ликийский язык (The Lycian language), in: Языки мира: Реликтовые индоевропейские языки Передней и Центральной Азии (Languages of the World: Relict Indo-European languages of Western and Central Asia)". Языки Мира: Реликтовые Индоевропейские Языки Передней И Центральной Азии ["Languages of the World: Relict Indo-European Languages of Western and Central Asia"] (Edd. Y.b. Koryakov & A.a. Kibrik), Moscow, 2013, 131-154. Moscow: Москва Academia: 131–154. Retrieved 2021-04-17. (in Russian)

- Calin, Didier (January 2019). "A short English-Lycian/Milyan lexicon". Academia. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- Neumann, Günther (1969), "Lydisch". In: Handbuch der Orientalistik, II. Band, 1. und 2. Abschnitt, Lieferung 2, Altkleinasiatische Sprachen, Leiden/Köln: Brill, pp. 358-396: p. 386.

- Billings, Nils Oscar Paul. "Finite verb formation in Lycian" (thesis), Leiden 2019.

- Sasseville, David (2020). Anatolian Verbal Stem Formation: Luwian, Lycian and Lydian. Leiden / Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004436282.

- Only attested in Lycian B.

- Billings (2019), pp. 116-118.

- Laroche, Emmanuel (1979). "L'inscription lycienne". Fouilles de Xanthos. VI: 51–128: 95–98.

- Inscription TL 19 from Pinara.

- McCone, Kim (1979). "The Diachronic Possibilities of the IE "Amplified" Sentence". In Brogyanyi, Bela (ed.). Studies in Diachronic, Synchronic, and Typological Linguistics: Festschrift for Oswald Szemerényi on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-3504-6. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- Melchert, H. Craig (2021). "Lycian relative clauses" (PDF). Hungarian Assyriological Review. Budapest. 2 (1): 65–75. doi:10.52093/hara-202101-00013-000. S2CID 249356921.

- Inscription TL 40 from Xanthos.

- Inscription TL 104 from Limyra.

- Inscription TL 31 from Kadyanda.

- Strabo 7.7.1, 13.1.59.

- Strabo 14.1.3, 14.2.18.

External links

- "Digital etymological-philological Dictionary of the Ancient Anatolian Corpus Languages (eDiAna)". Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

- "The Lycian language". Archived from the original on 16 October 2005.

- "Working group document on encoding the Lycian script" (PDF). in the Universal Character Set

- "Lycian text". University of Frankfurt.

References

- Adiego, I.J. (2007). "Greek and Lycian". In Christidis, A.F.; Arapopoulou, Maria; Chriti, Maria (eds.). A History of Ancient Greek From the Beginning to Late Antiquity. Translated by Markham, Chris. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (1986). The Lycians in Literary and Epigraphic Sources. The Lycians. Vol. I. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-023-1.