Imitation of Life (1959 film)

Imitation of Life is a 1959 American drama film directed by Douglas Sirk, produced by Ross Hunter and released by Universal International. It was Sirk's final Hollywood film and dealt with issues of race, class and gender. Imitation of Life is the second film adaptation of Fannie Hurst's 1933 novel of the same name; the first, directed by John M. Stahl, was released in 1934.

| Imitation of Life | |

|---|---|

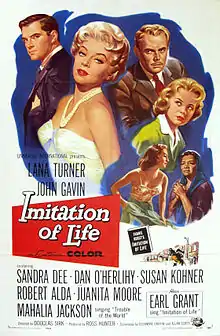

Film poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Douglas Sirk |

| Screenplay by | Eleanore Griffin Allan Scott |

| Based on | Imitation of Life 1933 novel by Fannie Hurst |

| Produced by | Ross Hunter |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | Milton Carruth |

| Music by |

|

| Color process | Eastmancolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.2 million[3] |

| Box office | $6.4 million (est. US/ Canada rentals)[4] |

The film's top-billed stars are Lana Turner and John Gavin, and the cast also features Sandra Dee, Dan O'Herlihy, Susan Kohner, Robert Alda and Juanita Moore. Kohner and Moore received Academy Award nominations for their performances. Gospel music star Mahalia Jackson appears as a church choir soloist.

In 2015, the United States Library of Congress selected Imitation of Life for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." The original 1934 version of Imitation of Life was added to the National Film Registry in 2005.[5][6]

Plot

In 1947, single mother Lora Meredith dreams of becoming a famous Broadway actress. Losing track of her young daughter Susie at a crowded Coney Island beach, she asks a stranger, Steve Archer, to help her find the girl. Meanwhile, Susie has been found and looked after by Annie Johnson, who is also a single mother with a daughter, Sarah Jane, who is about Susie's age. With the help of Steve and a police officer, Lora is reunited with Susie. The Merediths are white and the Johnsons are black, but Lora initially assumes Sarah Jane is white and not Annie's daughter. Sarah Jane's fair skin allows her to pass as white and she fervently rejects being identified as black.

In return for Annie's kindness, Lora temporarily takes in Annie and her daughter. Annie persuades Lora to let her stay and look after the household so that she can pursue an acting career. Lora becomes a star of stage comedies, with Allen Loomis as her agent and David Edwards as her chief playwright (and lover). Although Lora had begun a relationship with Steve, their courtship falls apart because he does not want her to be a star. Lora's concentration on her career prevents her from spending time with Susie, who sees more of Annie. Annie and Sarah Jane have their own problems, as Sarah Jane is struggling with her identity.

Eleven years later, Lora is a highly regarded Broadway star living in a luxurious home near New York City. Annie continues to live with her, serving as nanny, housekeeper, confidante and best friend. After rejecting David's latest script (and his marriage proposal), Lora takes a role in a dramatic play. At the show's after-party, she encounters Steve, whom she has not seen in a decade. The two slowly begin rekindling their relationship, and Steve is reintroduced to Annie and the now-teenaged Susie and Sarah Jane. When Lora is signed to star in an Italian movie, she leaves Steve to watch after Susie. The teenager develops an unrequited crush on her mother's boyfriend.

Sarah Jane begins dating a white teenager, but he beats her in an alleyway after learning she is black. Sometime later, she again passes for white to get a job performing at a seedy nightclub but tells her mother she is working at the library. When Annie learns the truth, she goes to the club to claim her daughter; Sarah Jane is subsequently fired. Sarah Jane's rejection of her mother takes a physical and mental toll on Annie. When Lora returns from Italy, Sarah Jane has run away from home, leaving Annie a note that says if she truly does care about her, she will leave her alone and let her live her life.

Lora asks Steve to hire a private detective to find Sarah Jane. The detective finds her living and working in California as a white woman under an assumed name. Annie, becoming weaker and more depressed by the day, flies out to see her daughter one last time and say goodbye. Upon meeting with Sarah Jane, Annie apologizes for being selfish by loving her too much and wishes her the best. She pleads to Sarah Jane that if she ever needs help, she will reach out to her, and the two share an embrace. Sarah Jane's roommate interrupts them and presumes Annie is a maid. Annie tells the roommate that she is a former nanny of "Miss Linda," Sarah Jane's new name.

Annie is bedridden upon her return to New York and Lora and Susie look after her. The issue of Susie's crush on Steve becomes serious when she learns that Steve and Lora are to be married. Annie tells Lora of the girl's crush. After a confrontation with her mother, Susie decides to go away to school in Denver to forget about Steve. Soon after their argument, Annie dies with Lora crying hysterically by her side. As she wished, Annie is given a lavish funeral in a large church, complete with a gospel choir, followed by an elaborate traditional funeral procession with a band and four white horses drawing the hearse. Just before the procession sets off, a bereaved and guilt-ridden Sarah Jane pushes through the crowd of mourners to throw herself upon her mother's casket apologizing and begging forgiveness, proclaiming, "I killed my own mother!" Lora takes Sarah Jane to their limousine to join her, Susie, and Steve as the procession slowly travels through a city street. A large African American crowd silently watches.

Cast

- Lana Turner as Lora Meredith

- Juanita Moore as Annie Johnson

- John Gavin as Steve Archer

- Sandra Dee as Susie, age 16

- Susan Kohner as Sarah Jane, age 18 (singing voice dubbed by Jo Ann Greer)

- Robert Alda as Allen Loomis

- Dan O'Herlihy as David Edwards

- Karin Dicker as Sarah Jane, age 8

- Terry Burnham as Susie, age 6

- Sandra Gould as Annette

- Mahalia Jackson as choir soloist

- Than Wyenn as Romano

- Troy Donahue as Frankie

- Jack Weston as Tom

- Ann Robinson as Showgirl

History and production

The plot of the 1959 version of Imitation of Life has numerous major changes from those of the original book and the 1934 film version.[7] In the original story, the "Lora" character, Bea Pullman, became successful by commercial production of her maid Delilah's family waffle recipe (a pancake recipe in the 1934 film version). As a result, Bea, the white businesswoman, becomes rich. Delilah is offered 20% of the profits, but declines and chooses to remain Bea's dutiful assistant. Like the previous film, in this one the Peola (Sarah Jane) character returns, going to her mother's funeral and showing remorse, a scene described by Molly Hiro as "virtually identical" to the previous one, while in the novel she leaves the area for good.[7]

Director Douglas Sirk and screenwriters Eleanore Griffin and Allan Scott felt that such a story would not be accepted during the Civil Rights Movement, amid milestones such as the Brown v. Board of Education case and the Montgomery bus boycott, but racial discrimination and inequities were still part of it. The story was altered so that Lora becomes a Broadway star with her own talents, with Annie assisting her by serving as a nanny for Lora's child. Producer Ross Hunter was cannily aware that these plot changes would enable Lana Turner to model an array of glamorous costumes and real jewels, something that would appeal to the female audience at that time. Lana Turner's wardrobe for Imitation of Life cost over $1.078 million, making it one of the most expensive in cinema history at that time.[8]

Although many actresses, most of them white,[9] were screen-tested for the Sarah Jane role in the 1959 remake, Susan Kohner, daughter of actress Lupita Tovar, born in Mexico, and Paul Kohner, a Czech-Jewish immigrant, won the role.[9] Karin Dicker made her debut in this film as the young Sarah Jane. Noted gospel singer Mahalia Jackson received "presenting" billing for her one scene, performing a version of "Trouble of the World" at Annie's funeral service.

Release and critical reaction

Sirk's Imitation of Life premiered in Chicago on March 17, 1959, followed by Los Angeles on March 20 and New York City on April 17.[2] Following its New York opening, it became number one in the US for two weeks[10] before Universal put the film into general release on April 30. Though it was not well-reviewed upon its original release and was viewed as inferior to the original 1934 film version – many critics derided the film as a "soap opera"[11] – Imitation of Life was the sixth highest-grossing film of 1959, grossing $6.4 million,[12] and was Universal-International's top-grossing film that year. Hiro wrote that in contrast to the novel, this film and the previous film received "far more critical attention", with the second film being "more famous" than the first.[7]

Both Moore and Kohner were nominated for the 1959 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress and the 1959 Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actress. While neither actress won the Oscar, Kohner won the Golden Globe for her performance. Moore won second place in the category of Top Female Supporting Performance at the 1959 Laurel Awards, and the film won Top Drama. Douglas Sirk was nominated for the 1959 Directors Guild of America Award.[13]

Since the late 20th century, Imitation of Life has been re-evaluated by critics. It has been considered a masterpiece of Sirk's American career. Emanuel Levy has written "One of the four masterpieces directed in the 1950s, the visually lush, meticulously designed and powerfully acted Imitation of Life was the jewel in Sirk's crown, ending his Hollywood's career before he returned to his native Germany."[14] Sirk provided the Annie–Sarah Jane relationship in his version with more screen time and more intensity than the original versions of the story. Critics later commented that Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner stole the film from Turner.[8] Sirk said that he had deliberately and subversively undercut Turner to draw focus toward the problems of the two black characters.

Sirk's treatment of racial and class issues is also admired for what he caught of the times. Writing in 1997, Rob Nelson said,

Basically, we're left to intuit that the black characters (and the movie) are themselves products of '50s-era racism – which explains the film's perspective, but hardly makes it less dizzying. Possibly thinking of W.E.B. Du Bois's notion of black American double-consciousness, critic Molly Haskell once described Imitation's double-vision: "The mixed-race girl's agonizing quest for her identity is not seen from her point of view as much as it is mockingly reflected in the fun house mirrors of the culture from which she is hopelessly alienated."[15]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 84% of 31 reviews are positive, and the average rating is 7.8/10. The site's consensus reads, "Douglas Sirk enriches this lush remake of Imitation of Life with racial commentary and a sharp edge, yielding a challenging melodrama with the power to devastate."[16] On Metacritic — which assigns a weighted mean score — the film has a score of 87 out of 100 based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[17]

In 2015, BBC Online named the film the 37th greatest American movie ever made, based on a survey of film critics.[18]

Awards and nominations

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Susan Kohner | Nominated | [19] |

| Juanita Moore | Nominated | |||

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Douglas Sirk | Nominated | [20] |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Susan Kohner | Won | [21] |

| Juanita Moore | Nominated | |||

| Laurel Awards | Top Drama | Won | ||

| Top Female Supporting Performance | Juanita Moore | Nominated | ||

| Top Cinematography – Color | Russell Metty | Nominated | ||

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Inducted | [22] | |

Home media

Both the 1934 and 1959 films were issued in 2003 on a double-sided DVD from Universal Studios. A two-disc set of the films was issued by Universal in 2008. A Blu-ray with both films was released in April 2015;[23] this edition has been re-mastered, and is not identical with earlier DVD releases.[24]

Madman Entertainment in Australia released a three-disc DVD set, including the 1934 film version as well as a video essay on the 1959 film by Sam Staggs.[25]

In popular culture

Todd Haynes' Far from Heaven (2002) is an homage to Sirk's work, in particular All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Imitation of Life.

The 1969 Diana Ross & the Supremes song "I'm Livin' in Shame" is based upon this film.[26]

The 2001 R.E.M. song "Imitation of Life" took its title from the film, though none of the band members had ever watched it.[27]

References

- Imitation of Life at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "Imitation of Life - Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- Archer, Eugene (16 October 1960). "HUNTER OF LOVE, LADIES, SUCCESS". New York Times. p. X9.

- "1959: Probable Domestic Take", Variety, 6 January 1960 p 34

- Mike Barnes (December 16, 2015). "'Ghostbusters,' 'Top Gun,' 'Shawshank' Enter National Film Registry". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- Hiro, Molly (Winter 2010). "'Tain't no tragedy unless you make it one': Imitation of Life, Melodrama, and the Mulatta". Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory. Johns Hopkins University Press. 66 (4): 94. doi:10.1353/arq.2010.a406967. S2CID 141801126.

- Handzo, Steven (1977). "Intimations of Lifelessness". Bright Lights Film Journal (6). Retrieved 2013-03-09.

Turner wears $1,000,000 worth of jewels in the film and a $78,000 Jean Louis wardrobe — 34 costume changes at an average cost of $2,214.13 each. [referring to the cost of the wardrobe]

- Foster Hirsch (April 9, 2015). "Imitation of Life". Film Forum (Podcast). Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- "National Boxoffice Survey". Variety. May 5, 1959. p. 3. Retrieved June 16, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- Gallagher, Tag (July 2005). "White Melodrama: Douglas Sirk". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

The critics had barfed all over the film, hating it as "a soap opera" for the same reasons Sirk and we loved it.

- "Database: 1959". Box Office Report. Retrieved from http://www.boxofficereport.com/database/1959.shtml Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine on January 16, 2007.

- Awards and nominations for Imitation of Life. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052918/awards on January 16, 2007.

- Levy, Emanuel (August 15, 2009). "Imitation of Life (1959)".

- Nelson, Rob (June 11, 1997). "Passing Time/ Through a Glass, Darkly: Juanita Moore and Lana Turner in Douglas Sirk's 'Imitation of Life". Minneapolis City Pages. Archived from the original on 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- "Imitation of Life". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- "Imitation of Life (1959) Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- "The 100 Greatest American Films". bbc.com. July 20, 2015.

- "The 32nd Academy Awards (1960) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- "12th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Imitation of Life – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Imitation of Life (DVD (Blu-ray)). Universal Studios. April 7, 2015.

- Tooze, Gary W. (2015). "Imitation of Life Blu-ray Lana Turner Claudette Colbert". DVDBeaver.

- Imitation of Life (DVD). Madman Entertainment. April 23, 2008. OCLC 269454090.

- Ribowsky, Mark (2009). The Supremes: A Saga of Motown Dreams, Success, and Betrayal. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-306-81586-7.

- In Time: The Best of R.E.M. 1988–2003 (US CD album booklet notes). R.E.M. Warner Bros. Records. 2001. 2-48550.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

Further reading

- Fischer, Lucy, ed. (1991). Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1645-5. OCLC 22279801. Collection of essays, reviews, interviews, and source materials related to Imitation of Life.

- Staggs, Sam (2009). Born To Be Hurt: The Untold Story of Imitation of Life. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-37336-8. OCLC 234176069.

- Ryan, Tom. "Sirk and John M. Stahl: Adaptations and Remakes". In Tom Ryan (ed.). The Films of Douglas Sirk: Exquisite Ironies and Magnificent Obsessions.

External links

- Imitation of Life essay by Matthew Kennedy on the National Film Registry website

- Imitation of Life at IMDb

- Imitation of Life at the TCM Movie Database

- Imitation of Life at AllMovie

- Imitation of Life at Rotten Tomatoes

- Imitation of Life at the American Film Institute Catalog