Cartography of India

The cartography of India begins with early charts for navigation[1] and constructional plans for buildings.[2] Indian traditions influenced Tibetan[3] and Islamic traditions,[4] and in turn, were influenced by the British cartographers who solidified modern concepts into India's map making.[5]

|

| History of science and technology in the Indian subcontinent |

|---|

| By subject |

A prominent foreign geographer and cartographer was Hellenistic geographer Ptolemy (90–168) who researched at the library in Alexandria to produce a detailed eight-volume record of world geography.[5] During the Middle Ages, India sees some exploration by Chinese and Muslim geographers, while European maps of India remain very sketchy. A prominent medieval cartographer was Persian geographer Abu Rayhan Biruni (973–1048) who visited India and studied the country's geography extensively.[6]

European maps become more accurate with the Age of Exploration and Portuguese India from the 16th century. The first modern maps were produced by Survey of India, established in 1767 by the British East India Company. Survey of India remains in continued existence as the official mapping authority of the Republic of India.

Prehistory

Joseph E. Schwartzberg (2008) proposes that the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization (c. 2500–1900 BCE) may have known "cartographic activity" based on a number of excavated surveying instruments and measuring rods and that the use of large scale constructional plans, cosmological drawings, and cartographic material was known in India with some regularity since the Vedic period (1st millennium BCE).[7]

- 'Though not numerous, a number of map-like graffiti appear among the thousands of Stone Age Indian cave paintings; and at least one complex Mesolithic diagram is believed to be a representation of the cosmos.'[8]

Susan Gole (1990) comments on the cartographic traditions in early India:

The fact that towns as far apart as Mohenjodaro near the Indus and Lothal on the Saurashtra coast were built in the second millennium BCE with baked bricks of identical size on similar plans denotes a widespread recognition of the need for accuracy in planning and management. In the 8th century CE the Kailas temple at Ellora in Maharashtra was carved down into mountain for 100 feet, with intricate sculptures lining pillared halls, no easy task even with an exact map to follow, impossible without. So if no maps have been found, it should not be assumed that the Indians did not know how to conceptualize in a cartographic manner.[2]

Antiquity

Cartography of India as a part of the greater continent of Asia develops in Classical Antiquity.

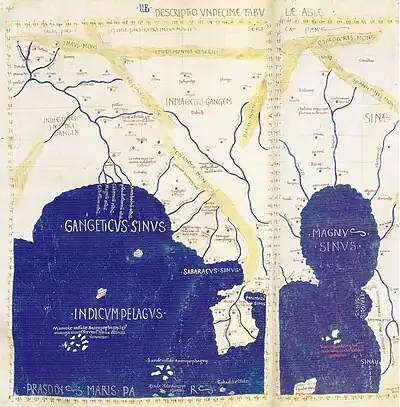

In Greek cartography, India appears as a remote land on the eastern fringe of Asia in the 5th century BCE (Hecataeus of Miletus). More detailed knowledge becomes available after the conquests of Alexander the Great, and the 3rd-century BCE geographer Eratosthenes has a clearer idea of the size and location of India. By the 1st century, at least the western coast of India is well known to Hellenistic geography, with itineraries such as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Marinus and Ptolemy had some knowledge of the Indian Ocean (which they considered a sea) but their Taprobana (Sri Lanka) was vastly too large and the Indian peninsula much reduced. They also had little knowledge of the interior of the country.

Native Indian cartographic traditions before the Hellenistic period remain rudimentary. Early forms of cartography in India included legendary paintings; maps of locations described in Indian epic poetry, for example the Ramayana.[9] These works contained descriptions of legendary places, and often even described the nature of the mythological inhabitants of a particular location.[9] Early Indian cartography showed little knowledge of scale, the important parts of the map were shown to be larger than others (Gole 1990). Indian cartographic traditions also covered the locations of the Pole star, and other constellations of use.[1] These charts may have been in use by the beginning of the Common Era for purposes of navigation.[1] Other early maps in India include the Udayagiri wall sculpture—made under the Gupta empire in 400 CE—showing the meeting of the Ganges and the Yamuna.[10]

Middle Ages

The 8th-century poet and dramatist Bhavabhuti, in Act 1 of the Uttararamacarita, described paintings which indicated geographical regions.[11] In the 20th century, over 200 medieval Indian maps were studied in the compilation of a history of cartography. Also considered in the study were copper-plate text inscriptions on which the boundaries of land, granted to the Brahman priests of India by their patrons, were described in detail.[2] The descriptions indicated good geographical knowledge and in one case over 75 details of the land granted have been found.[2] The Chinese records of the Tang dynasty show that a map of the neighboring Indian region was gifted to Wang Hiuen-tse by its king.[12]

In the 9th century, Islamic geographers under Abbasid Caliph Al-Ma'mun improved on Ptolemy's work and depicted the Indian Ocean as an open body of water instead of a land-locked sea as Ptolemy had done.[13] The Iranian geographers Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī and Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi set the Prime Meridian of their maps at Ujjain, a centre of Indian astronomy.[14] In the early 11th century, the Persian geographer Abu Rayhan Biruni visited India and studied the country's geography extensively.[6] He was considered the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the western Indian subcontinent. He also wrote extensively on the geology of India.[15] In 1154, the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi included a section on the cartography and geography of India and its neighboring countries in his world atlas, Tabula Rogeriana.[16]

Italian scholar Francesco Lorenzo Pullè reproduced a number of Indian maps in his magnum opus La Cartografia Antica dell'India.[11] Out these maps two have been reproduced using a manuscript of Lokaprakasa—originally compiled by the polymath Ksemendra (Kashmir, 11th century CE)—as a source.[11] The other manuscript, used as a source by Francesco Pullè, is titled Samgrahani.[11] The early volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica also described cartographic charts made by the Dravidian people of India.[1][17]

The cartographic tradition of India influenced the map making tradition of Tibet, where maps of Indian origin have been discovered.[3] Islamic cartography was also influenced by the Indian tradition as a result of extensive contact.[4]

The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached the subcontinent on 20 May 1498, anchoring off Calicut, on Malabar Coast. He would, with other Portuguese, navigate and chart much of the sub-continents coast line, within decades. These charts were rapidly reproduced, and appeared in say the 1502 Cantino planisphere.

Mughal era

Maps from the 1590 Ain-e-Akbari, a Mughal document detailing India's history and traditions, contain references to locations indicated in earlier Indian cartographic traditions.[11]

Through the 16th century European explorers, and traders, such as Jan Huygen van Linschoten ventured into the interior, from the growing number or European trading posts, and expanded on and refined the previous navigational charts, with geographic detail. A series of geographies published under the title Itinerario (later published as an English edition as Discours of Voyages into Y East & West Indies), appeared in 1596, and graphically displayed for the first time in Europe detailed maps of voyages to the East Indies, particularly India.

The seamless hollow Celestial globe was invented in Kashmir by Ali Kashmiri ibn Luqman in 998 AH (1589–90 CE), and twenty other such globes were later produced in Lahore and Kashmir during the Mughal Empire.[18] Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce hollow metal globes without any seams, even with modern technology.[18] These Mughal metallurgists pioneered the method of lost-wax casting in order to produce these globes.[18]

The scholar Sadiq Isfahani of Jaunpur compiled an atlas of the parts of the world which he held to be 'suitable for human life'.[10] The 32 sheet atlas—with maps oriented towards the south as was the case with Islamic works of the era—is part of a larger scholarly work compiled by Isfahani during 1647 CE.[10] According to Joseph E. Schwartzberg (2008): 'The largest known Indian map, depicting the former Rajput capital at Amber in remarkable house-by-house detail, measures 661 × 645 cm. (260 × 254 in., or approximately 22 × 21 ft).'[19]

Colonial India

A map describing the kingdom of Nepal, four feet in length and about two and a half feet in breadth, was presented to Warren Hastings.[9] In this raised-relief map the mountains were elevated above the surface and several geographical elements were indicated in different colors.[9] The Europeans used 'scale-bars' in their cartographic tradition.[2] Upon their arrival in India during the middle ages, the indigenous Indian measures were reported back to Europe, and first published by Guillaume de I'Isle in 1722 as Carte des Costes de Malabar et de Coromandel.[2]

With the establishment of the British Raj in India, modern European cartographic traditions were officially employed by the British Survey of India (1767). One British observer commented on the tradition of native Indian cartography:

Besides geographical tracts, the Hindus have also maps of the world according to the system of the puranics and of the astronomers: the latter are very common. They also have maps of India and of particular districts, in which latitudes and longitudes are entirely out of question, and they never make use of scale of equal parts. The sea shores, rivers and ranges of mountains are represented by straight lines.[9]

The Great Trigonometric Survey, a project of the Survey of India throughout most of the 19th century, was piloted in its initial stages by William Lambton, and later by George Everest. To achieve the highest accuracy a number of corrections were applied to all distances calculated from simple trigonometry:

- Curvature of the Earth

- The non spherical nature of the curvature of the Earth

- Gravitational influence of mountains on pendulums

- Refraction

- Height above sea level

Thomas George Montgomerie organized several cartographic expeditions to map Tibet, as well as China.[20] Mohamed-i-Hameed, Nain Singh and Mani Singh were among the agents employed by the British for their cartographic operations.[20] Nain Singh, in particular, became famous for his geographical knowledge of Asia, and was awarded several honors for his expeditions.[21]

Modern India (1947 to present)

The modern map making techniques in India, like other parts of the world, employ digitization, photographic surveys and printing.[22] Satellite imageries, aerial photographs and video surveying techniques are also used.[22] The Indian IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was equipped with high resolution panchromatic equipment to enable it for cartographic purposes.[23] IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was followed by a more advanced model named IRS-P6 developed also for agricultural applications.[23] The CARTOSAT-2 project, equipped with single panchromatic camera which supported scene specific on-spot images, succeed the CARTOSAT-1 project.[23]

See also

Notes

- Sircar, 330

- Gole (1990)

- Sircar, 329

- Pinto (2006)

- Fuechsel (2008)

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Schwartzberg, 1301–1302

- Schwartzberg, 1301

- Sircar, page 327

- Schwartzberg, 1302

- Sircar, 328

- Sircar, 326.

- Covington (2007)

- Kennedy, 189

- Salam (1984)

- See Ahmad, S. Maqbul (1960), Al-Sharif al-Idrisi: India and the Neighbouring Territories

- See Encyclopædia Britannica, 14th edition, volume XIV, 840–841.

- Savage-Smith (1985)

- Schwartzberg, 1303

- Nagendra (1999)

- In 1876, his achievements were announced in the Geographical Magazine. The awards and recognition soon started flowing in. On his retirement, the Indian Government honoured him with the grant of a village, and 1000 rupees in revenue. The crowning achievement came in 1876, when the Royal Geographical Society honoured him with a gold medal as the ‘man who has added a greater amount of positive knowledge to the map of Asia than any individual of our time—Nagendra 1999.

- See Indian Express (1999). Modern map-making techniques on display. Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) Ltd.

- Burleson, D. (2005), "India", Space Programs Outside the United States: All Exploration and Research Efforts, Country by Country, McFarland, 136–146, ISBN 0-7864-1852-4.

References

- Covington, Richard (2007), Saudi Aramco World (May–June 2007), pp. 17–21.

- Fuechsel, Charles F. (2008), "map", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gole, Susan (2008). "Size as a measure of importance in Indian cartography". Imago Mundi. 42 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1080/03085699008592695. JSTOR 1151051.

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1996), "Mathematical Geography", Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science (1 & 3) edited by Rushdī Rāshid & Régis Morelon, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12410-7.

- Nagendra, Harini (1999), Re-discovering Nain Singh, Indian Institute of Science.

- Pinto, Karen (2006), "Cartography", Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia edited by Josef W. Meri & Jere L. Bacharach, pp. 138–140, Taylor & Francis.

- Salam, Abdus (1984), "Islam and Science", Ideals and Realities: Selected Essays of Abdus Salam (2nd ed.) edited by C. H. Lai (1987), pp. 179–213, World Scientific.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their history, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (2008), "Maps and Mapmaking in India", Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures (2nd edition) edited by Helaine Selin, pp. 1301–1303, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- Sircar, D.C.C. (1990), Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-0690-5.