Aboriginal title in the United States

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title (also known as "original Indian title" or "Indian right of occupancy"). Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

The power of Congress to extinguish aboriginal title—by "purchase or conquest," or with a clear statement—is plenary and exclusive. Such extinguishment is not compensable under the Fifth Amendment, although various statutes provide for compensation. Unextinguished aboriginal title provides a federal common law cause of action for ejectment or trespass, for which there is federal subject-matter jurisdiction. Many potentially meritorious tribal lawsuits have been settled by Congressional legislation providing for the extinguishment of aboriginal title as well as monetary compensation or the approval of gaming and gambling enterprises.

Large-scale compensatory litigation first arose in the 1940s, and possessory litigation in the 1970s. Federal sovereign immunity bars possessory claims against the federal government, although compensatory claims are possible by statute. The Eleventh Amendment bars both possessory and compensatory claims against states, unless the federal government intervenes. The US Supreme Court rejected nearly all legal and equitable affirmative defenses in 1985. However, the Second Circuit—where most remaining possessory claims are pending—has held that laches bars all claims that are "disruptive."

History

Before 1776

Before 1763, the Colonial history of the United States was characterized by private purchases of lands from Indians. Many of the earliest deeds in the Eastern states purport to commemorate such transactions.

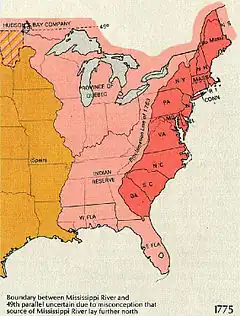

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 changed matters, reserving for the Crown the exclusive right of preemption, requiring all such purchases to have Royal approval. It was also an attempt to restrain colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains (see map). Forged versions of the Pratt-Yorke opinion of 1757 (in its authentic form, a joint opinion of Britain's Attorney General and Solicitor General regarding land purchases in India) were circulated in the colonies, edited such that it appeared to apply to purchases from Native Americans.

The Royal Proclamation was among the enumerated complaints in the Declaration of Independence:

He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose ... raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

1776–1789

The Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 prohibited the extinguishment of aboriginal title without the consent of Congress. But, the states, particularly New York, purchased lands from tribes during this period without the consent of the federal government. These purchases were not tested in court until the 1970s and 1980s, when the Second Circuit held that the Confederation Congress had neither the authority under the Articles of Confederation nor the intent to limit the ability of states to extinguish aboriginal title within their borders; thus, the Proclamation was interpreted to apply only to the federal territories.

Since 1789

States had lost the ability to extinguish aboriginal title with the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788, which vested authority over commerce with American Indian tribes in the federal government. Congress codified this prohibition in the Nonintercourse Acts of 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1833.

Marshall Court

The Marshall Court (1801—1835) issued some of the earliest and most influential opinions on the status of aboriginal title in the United States, most of them authored by Chief Justice John Marshall. But, without exception, the remarks of the Court on aboriginal title during this period are dicta.[1] Only one indigenous litigant ever appeared before the Marshall Court, and there, Marshall dismissed the case for lack of original jurisdiction.

Fletcher v. Peck (1810) and Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), the first and the most detailed explorations of the subject by Marshall, respectively, both arose out of collusive lawsuits, where land speculators deceived the court with a falsified case and controversy in order to elicit the desired precedent.[2][3] In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the dicta of Marshall and the dissenting justices embraced a far broader view of aboriginal title.

Johnson involved a pre-Revolutionary private conveyances from 1773 and 1775; Mitchel v. United States (1835) involved 1804 and 1806 conveyances in Florida under Spanish rule. In both cases, the Marshall Court continued to apply the rule that aboriginal title was inalienable, except to The Crown.

Removal era

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 established policy that resulted in the complete extinguishment of aboriginal title in Alabama and Mississippi (1832); Florida and Illinois (1833); Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee (1835) [the Treaty of New Echota]; Indiana (1840); and Ohio (1842).[4]

Reservation, treaty, and termination eras

This shift in policy resulted in all tribal lands being either ceded to the federal government or designated as an Indian reservation in Iowa, Minnesota, Texas, and Kansas by 1870; Idaho, Washington, Utah, Oregon, Nevada, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado by 1880; and Montana, Arizona, and New Mexico by 1886.[5] Whereas, "it had taken whites 250 years to purchase the Eastern half of the United States, ... they needed less than 40 years for the Western half."[5] Unlike the Eastern purchases, "some of the transactions in the West involved immense areas of land. More than 75 percent of Nevada, for example, was acquired in two bites; the large majority of Colorado in three. It was not long before the West was dotted with Indian reservations."[5]

Congress banned further Indian treaties by statute in 1871, but treaty-like instruments continued to be used to alienate Indian land and designate the boundaries of reservations.[6] Language in an 1881 Indian Country bill—referring to "lands to which the original Indian title has never been extinguished"—was struck by its sponsors, who claimed that "there are no such lands in the United States."[7]

In 1887, the Dawes Act introduced an allotment policy, whereby communal reservation lands were divided into parcels held in fee simple (and thus alienable) by individual Indians, with the "surplus," as declared by the government, sold to non-Indians. Allotment ended in 1934.[8]

1940s—present

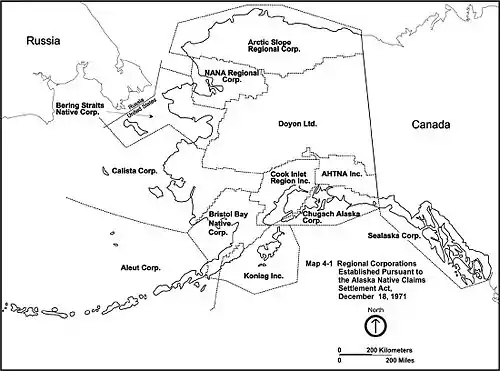

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971) extinguished all aboriginal title in Alaska (although the legitimacy of the act remains disputed by some Alaskan natives[9][10]). Indian Land Claims Settlements extinguished all aboriginal title in Rhode Island (1978) and Maine (1980).

According to Prof. Stuart Banner:

- [T]he story of Indians and land over the past sixty years has primarily been that of tribes' efforts to get land back, or to be compensated for land wrongfully taken. Indians have directed land claims at every branch of the federal government—at Congress, at the courts, at the Interior Department, and, for the 1940s to the 1970s, at the purpose-built administrative agency called the Indian Claims Commission. Some of these claims have been remarkably successful, culminating either directly in court judgements or indirectly in legislative settlements.[11]

Sources of law

Constitution of the United States

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 3 provides:

[The Congress shall have Power] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes;

Federal treaties

Federal statutes

Relevant federal statutes include:

- Royal Proclamation of 1763 (British North America)

- Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 (Articles of Confederation-era)

- Northwest Ordinance (1787)

- Nonintercourse Act (1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, 1834)

- Indian Removal Act (1830)

- Dawes Act (1887)

- Curtis Act of 1898

- Indian Reorganization Act (1934)

- Indian Claims Commission Act (1946)

- Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971)

- Indian Land Claims Settlements (1978–2006)

- Indian Claims Limitations Act (1982)

State constitutions and statutes

New York

N.Y. Const. of 1777 art. XXXVII provided:

And whereas it is of great importance to the safety of this State that peace and amity with the Indians within the same be at all times supported and maintained; and whereas the frauds too often practiced towards the said Indians, in contracts made for their lands, have, in divers instances, been productive of dangerous discontents and animosities: Be it ordained, that no purchases or contracts for the sale of lands, made since the fourteenth day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, or which may hereafter be made with or of the said Indians, within the limits of this State, shall be binding on the said Indians, or deemed valid, unless made under the authority and with the consent of the legislature of this State.

N.Y. Const. of 1821 art. VII, § 12 provided:

[Indian lands.]—No purchase or contract for the sale of lands in this state, made since the fourteenth day of October, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, or which may hereafter be made, of or with the Indians in this state, shall be valid, unless made under the authority, and with the consent, of the legislature.

N.Y. Const. of 1846 art. I, § 16 provided:

[Indian lands.]—No purchase or contract for the sale of lands in this state, made since the fourteenth day of October, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, or which may hereafter be made, of or with the Indians, shall be valid unless made under the authority and with the consent of the legislature.

N.Y. Const. of 1894 art. 1, § 15 and N.Y. Const. of 1938 art I. § 13 provided:

[Purchase of lands of Indians.]-No purchase or contract for the sale of lands in this State, made since the fourteenth day of October, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five; or which may hereafter be made, of, or with the indians, shall be valid, unless made under the authority, and with the consent of the Legislature.

§ 13 was repealed on November 6, 1962, by popular vote.

Doctrine

Acknowledgement

The test for the acknowledgement of aboriginal title in the United States is actual, exclusive and continuous use and occupancy for a "long time".[12] Unlike nearly all common law jurisdictions, the United States acknowledges that aboriginal title may be acquired post-sovereignty; a "long time" can mean as little as 30 years.[13] However, the requirement of exclusivity may prevent any tribe from claiming aboriginal title where multiple tribes once shared the same area.[14] Improper designation of an ancestral group may also bar acknowledgement.[15]

'Cramer v. United States' (1923) was the first Supreme Court decision to acknowledge the doctrine of individual aboriginal title, not held in common by tribes.[16] Individual aboriginal title may be an affirmative defense to crimes such as trespassing on US Forest Service lands.[17] However, a claimant asserting individual aboriginal title must show that his or her ancestors held aboriginal title as individuals.[18]

Content

Where tribal land has previously been dispossessed, the tribe cannot unify its aboriginal title with purchased fee simple to reconstitute "Indian Country" for the purposes of tribal sovereignty in the United States.[19] Similarly, states can tax and exercise criminal jurisdiction in alienated tribal land, whether or not the tribe reacquires it.[20][21][22] Nor can Indians tax non-Indians who own land in fee simple otherwise within their jurisdiction.[23]

Courts has not been receptive to the view that aboriginal title was converted to fee simple during the rule of other countries (e.g. Russia in Alaska).[24]

The Nonintercourse Act does not prohibit leases.[25]

Extinguishment

The modern test for extinguishment of aboriginal title was most thoroughly explained in United States v. Santa Fe Pacific R. Co. (1941): extinguishment must come from Congress, or a part of the federal government properly delegated by Congress, and must satisfy a clear statement rule.[27][28] The earliest and most widely acknowledged method of extinguishing aboriginal title was by treaty.[29][30][31][32] Even fraud will not void the extinguishment of aboriginal title by the federal government (or by any actor, if the tribe waives the issue in the lower court).[33] Some cases hold that an executive order may extinguish aboriginal title,[34] although the dominant view is that the power lies with Congress.[15]

Extinguishment retroactively validates trespasses and removals of resources from aboriginal lands, and thus bars compensation (either statutory or constitutional) for those encroachments.[35]

Since 1790, states have not been able to extinguish aboriginal title. They cannot even foreclose on tribal lands due to the non-payment of taxes.[36] However, extinguishment by state governments before between independence and 1790 is generally valid.[37] The Second Circuit has held that states retained the power to purchase land directly from tribes during the Articles of Confederation period, and thus those purchases remain valid even if un-ratified by the federal government.[38]

The infamous Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903) held that Congress's power to extinguish was plenary, notwithstanding Indian treaties to the contrary.[39] While this decision has not been overruled per se, it has been modified in effect by the judicial enforcement of the federal government's fiduciary duty.

The rule of construction against extinguishment, even in the face of overlapping land grants, was based on the assumption that Congress would not lightly extinguish due to its "Christian charity."[40] Land grants themselves therefore do not extinguish aboriginal title, nor Indian usufructuary rights.[41] Furthermore, land grants are interpreted narrowly to avoid overlapping with unextinguished aboriginal title.[42][43]

Extinguishment can be accomplished through res judicata.[44] Extinguishment may also be effected through collateral estoppel following a final decision by a Court of Claims.[45] Even before a final ICC judgement, if a tribe claims compensation on the theory that its lands were extinguished, it cannot later attempt to claim valid title to those lands.[46] An ICC judgement acts as a bar to future claims,[47][48] and an ICC payment conclusively establishes extinguishment (although, for timing purposes, the ICC has not jurisdiction to extinguish).[49][50] Even though ICCA settlements are binding, the scope of the settlement may be up for debate.[51] The United States is bound by prior determinations as well.[52]

The Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act is an example of an act extinguishing aboriginal title.[53]

By geography

East of Mississippi

Indian removal policy resulted in the complete extinguishment of aboriginal title in Alabama and Mississippi (1832), Florida and Illinois (1833), Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee (1835) [the Treaty of New Echota], Indiana (1840), and Ohio (1842).[4]

Indian Land Claims Settlements extinguished all aboriginal title in Rhode Island in 1978[54] and Maine in 1980.[55] Similar, but non-statewide, acts extinguished some aboriginal title in Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, and New York.

The Vermont Supreme Court has held, in actions where aboriginal title was raised as a defense by criminal defendants, that all aboriginal title in Vermont was extinguished when Vermont became a state.[56] Commentators have criticized these decisions as inconsistent with federal law.[57]

Some eastern states argued that the Nonintercourse Act did not apply in the original colonies, or at least not in tribal areas surrounded by settlements. The First and Second Circuits have rejected this view, holding that the act applied in the entire United States.[55][58]

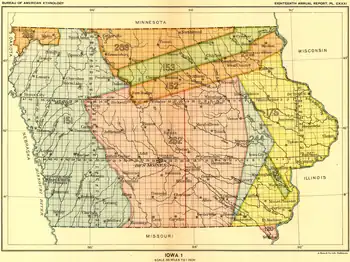

Indian cessions in Iowa

Indian cessions in Iowa Major Native American land cessions that resulted in what is now Michigan

Major Native American land cessions that resulted in what is now Michigan Land purchases in Pennsylvania

Land purchases in Pennsylvania Removal of the Five Civilized Tribes

Removal of the Five Civilized Tribes

Louisiana Purchase and Texas

Indian reservation policy resulted in the extinguishment of all aboriginal title outside of reservations in Iowa, Minnesota, Texas, and Kansas by 1870, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado by 1880, and Montana by 1886.[5]

The Fifth Circuit has held that the Louisiana Land Claims Act, requiring all persons with "incomplete title" to file claims, applied to aboriginal title. Thus, the Act extinguished aboriginal title on all lands conveyed before those acts.[59] Some of the statutes cited by the Fifth Circuit applied to Arkansas and Missouri as well.[60]

Mexican Cession

Indian reservation policy resulted in the extinguishment of all aboriginal title outside of reservations in Utah and Nevada by 1880, and Arizona and New Mexico by 1886.[5]

California was different. There, the Land Claims Act of 1851 required "each and every person claiming lands in California by virtue of any right or title derived by the Mexican government" to file their claim within two years.[61] Despite early authority to the contrary,[62] the established view is that the Act applied to aboriginal title, and thus extinguished all aboriginal title in California (as no tribes are known to have filed claims).[63] Cramer v. United States (1926) has distinguished this line of cases for individual aboriginal title.[16]

The above commentary is challenged below. In 1833, the Mexican government gave tribal communities a brief notice that they had the option to make modest claims upon Mission lands before each mission was closed and its property sold off. Most Spanish residents in the state failed to inform the tribal members of their rights to claim land, or had already driven most of the Mission Indians into the Sierras. In addition, once California became a state, federal rules required that Indian communities interact exclusively with the federal government. The 1894 U.S. Government report California Indian Reservations and Cessions includes the lost 18 treaties made between California tribes and the U.S. military that were then made secret by an act of Congress shortly after the treaties were forced upon at gunpoint by the U.S. Army on all of the state's tribes with the promise of lands.

Oregon territory

Indian reservation policy resulted in the extinguishment of all aboriginal title outside of reservations in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon in 1880.[5]

Alaska

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) extinguished all aboriginal title in Alaska in 1971.[64] Moreover, ANCSA extinguished every claim "based on" aboriginal title, such as trespass and breach of fiduciary duty (and even the extinguishment of these did not constitute a taking).[65][66] ANCSA has been interpreted not to apply offshore lands,[67][68] although it did extinguish some rights to hunt and fish offshore.[69]

Submerged lands

Title to the bed and banks of rivers, and the mineral rights therein, generally passes to states upon their gaining statehood.[70] However, this general doctrine does not apply where a tribe held treaty rights to the bed prior to statehood.[71] Additionally, tribes can gain title to dry lands formerly covered by rivers after a river changes course.[72] The United States can sue on behalf of tribes to gain title to those lands.[73]

The federal navigable servitude also bars the assertion of aboriginal title, although this may give rise to a claim for breach of fiduciary duty under the ICCA.[74]

Aboriginal title is absolutely extinguished to offshore submerged lands in the Outer Continental Shelf, however, under the doctrine of paramountcy.[68][75][76]

Guam

The Ninth Circuit assumed by did not decide that unextinguished aboriginal title remains in Guam, but held that the government of Guam had no standing to assert it.[77]

Possessory cause of action

For the first 100 years of the history of the United States, the doctrine of aboriginal title existed only in dicta supplied by decisions concerning land disputes between non-indigenous parties. It was generally assumed, but untested, that aboriginal title could be vindicated by causes of action such as ejectment and trespass.[78] Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy (1896), the first aboriginal title claim by an indigenous plaintiff to reach the U.S. Supreme Court, typifies the state of the law up until that point, and largely until the 1970s. The New York Court of Appeals ruled against the Seneca, both on the merits and on statute of limitations grounds, and the Supreme Court declined to review the decision because of adequate and independent state grounds.[79]

The situation changed dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida County (1974) ["Oneida I"] held for the first time that there was federal subject-matter jurisdiction for possessory claims by Indian tribes based upon aboriginal title.[80] Oneida County v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985) ["Oneida II"], held that there was a federal common law cause of action for such possessory claims, not pre-empted by the Nonintercourse Act, and rejected all of the counties' remaining affirmative defenses. Most importantly, Oneida II held that there was no statute of limitations applicable to such a cause of action, allowing the Oneida to challenge a conveyance from 1795.[81] The Second Circuit had also held that the Act creates an implied cause of action, a question the Supreme Court did not reach.

Oneida I and Oneida II opened the doors of the federal courts to dozens of high-profile land claims, especially in the former Thirteen Colonies, where tribal land continued to be purchased by the states without federal approval after the passage of the Constitution and the Nonintercourse Act.[82] Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton (1975) held that (even unrecognized) tribes could sue the federal government to compel it to bring suits against the state governments to vindicate Indian land claims.[55]

To have standing, plaintiffs must prove that the surviving tribal organization is the successor in interest to the historical tribe. Mashpee Tribe v. New Seabury Corp. (1979) is an example of a claim defeated by disproving this element.[83] The First Circuit has also held that the cause of action under the Nonintercourse Act accrues only to tribes, not individuals;[84] moreover, where a jury finds against tribal status, non-federally-recognized tribes are not entitled to reverse that holding as a matter of law.[85]

In suits against private parties, the United States is not a necessary party.[86][87] Similarly, historically, a court of equity could not set aside fraudulent transfers of aboriginal title unless all parties to the fraud were before it.[88] Old lower court decisions have expressed the view that aboriginal title is a political, non-justiciable question.[89] But, this view was subsequently rejected by the Supreme Court in Oneida II.

Compensatory causes of action

Constitutional

The Insular Cases seemed to take the view that aboriginal title was constitutionally protected property, at least within the Philippines.[90] In the 1930s and 1940s, the Supreme Court held that the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution required compensation for the taking of Indian lands when held in fee simple (as limited by treaty)[91][92] and treaty title.[93][94] It took the contrary view with a reservation created by executive order.[95] The taking of reservation land is now acknowledged as a taking.[96]

Tillamooks I (1946) was the closest the Supreme Court ever came to holding that unrecognized aboriginal title is property under the Fifth Amendment. Although the suit had been instituted under a special jurisdictional statute waiving the defense of sovereign immunity, the Court ordered compensation even while insisting that the statute itself had not created a property right; only the dissent referred to the Fifth Amendment.[97] According to the Ninth Circuit in Miller v. United States (1947), Tillamooks I held that even unrecognized aboriginal title is property under the Fifth Amendment, the extinguishment of which requires just compensation.[98] Although the issue was not raised in the case, a footnote in Hynes v. Grimes Packing (1949) repudiated the 9th Circuit view and insisted that aboriginal title was non-compensable.[99] Tillamooks II (1951) appeared to accept the Hynes view by denying interest to the compensation paid on remand following Tillamooks I.[100]

Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955) finally held that unrecognized aboriginal title was not property within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment, and thus could be extinguished without compensation.[101] Even the partition of a reservation does not implicate the Takings Clause,[102] nor the modification of ANCSA.[103] Recognized Indian title, unlike original Indian title, may give rise to Taking claims.[104] The claims court has sometimes refused takings claims, and thus denied interest, even where tribes were acknowledged to hold fee simple.[105]

Statutory

The Nonintercourse Act (discussed below) creates a trust relationship between tribes and the federal government, which is not easy to terminate.[106] The ICCA also acknowledges a cause of action for breach of "fair and honorable dealings."[107] This is compensable with money damages for breach of fiduciary duty.[108][109] This fiduciary duty gives rise for a claim of unconscionable compensation even when the transfer remains valid.[110][111] Liability under the fiduciary duty is sometimes the same whether the breach occurred before or after the ratification of the Constitution.[112] However, other cases have held that the duty did not arise until 1790.[113] This duty also gives rise to recovery for negligence, such as "surveying errors".[114][115] In no case would the ICCA compensate a tribe for harm by state governments.[113]

Prior to 1946, Native American land claims were explicitly barred from Claims Courts by statute. The Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946 (ICCA) created forum of Indian land claims before the Indian Claims Commission (subsequently merged into the United States Court of Claims, and then the United States Court of Federal Claims). However, the ICCA created a four-year statute of limitations.[86] Moreover, the ICC and its successors may award only money damages, and cannot—for example—title land. Finally, the ICCA is the exclusive forum to pursue claims against the federal government.[117]

In claims court, lands are valued at the date of purchase, not at present value, and without interest.[118] Recovery is limited to that fair market value, and may not be increased to another measure, such as restitution of the profit gained by the United States through breaching its duty.[119] Other payments or in-kind services may be offset from judgements.[120][121]

Affirmative defenses

Immunity

Federal sovereign immunity

Because of the ease with which the federal government may extinguish aboriginal title, and the fact that it may constitutionally do so without compensation, meritorious claims against the federal government are difficult to construct. Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation (1960) held that the Nonintercourse Act did not apply to the federal government.[122]

Additionally, the federal government cannot be sued without its consent. The federal government has consented to some compensatory suits under the Indian Claims Commission Act, supra, subject to a statute of limitations. Nor can the states sue the federal government in its capacity as guardian of the tribes.[123] Prior to the ICCA, private bills waived sovereign immunity for specific tribal complaints. The ICCA, and its amendments, also created a statute of limitations for claims against the federal government.[124]

- State sovereign immunity

The vast majority of allegedly illegal expropriation of tribal lands has occurred at the hands of states; however, regardless of the merits of these claims, states generally may not be sued.[127] The Eleventh Amendment, and the broader principle of state sovereign immunity derived from the structure of the Constitution, bars most suits against states without their consent. Although states may sue other states, the Supreme Court ruled in Blatchford v. Native Vill. of Noatak (1991) that tribes—even though they also enjoy sovereign immunity—have no greater ability to sue states than private individuals.[128] There are several exceptions to state sovereign immunity potentially relevant to aboriginal title claimants: the doctrine of Ex parte Young (1908), Congressional abrogation of state sovereign immunity by statute, and the ability of the federal government itself to sue states.

While—under Ex parte Young—tribes may obtain some prospective, equitable relief in suits nominally against state officials (generally, for treaty rights),[129] the Supreme Court in Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe (1997) held that state sovereign immunity barred not only quiet title suits but also suits against state officials which would constitute the equivalent of quiet title.[125] Although Coeur d'Alene involved sovereign title to a lake bed, this precedent has been applied to bar even suits against states in their capacity as ordinary property owners.[130]

There are at least two Congressional statutes which may have contemplated authorizing aboriginal title suits against states: the Nonintercourse Act and 28 U.S.C. § 1362, providing: "district courts shall have original jurisdiction of all civil actions, brought by any Indian tribe or band with a governing body duly recognized by the Secretary of the Interior, wherein the matter in controversy arises under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States."[131] The Supreme Court rejected the latter in Blatchford, supra; the Fifth Circuit rejected the former in 2000.[132] The Supreme Court mooted both in Seminole Tribe v. Florida (1996)—a suit under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act—when it held that Congress could not constitutionally abrogate state sovereign immunity under the Indian Commerce Clause, the basis for both statutes.[133] This holding has subsequently been expanded to nearly all of Congress's Article One powers,[134] leaving only the Reconstruction Amendments as a basis for abrogating state sovereign immunity.

Finally, the federal government may bring suits against states on behalf of the tribes in its guardian capacity, as it historically has.[126][135] Similarly, tribes may intervene in suits brought by the federal government (or the federal government may intervene in suits brought by the tribes) against states.[136] This exception is rather narrow, and states may assert sovereign immunity where tribes assert different claims, or ask for different relief, than the federal government.[137]

Statute of limitations/adverse possession

Oneida County v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985) ["Oneida II"] held that it would violate federal policy to apply the state statute of limitations to the federal cause of action for ejectment based on aboriginal title; thus, there is no statute of limitations.[81] Similarly, the widely held view is that aboriginal title cannot be adversely possessed. However, if a tribe is subject to an Indian Termination Act, the state statute of limitations (and any generally applicable state law) will apply to its land claim, as the Supreme Court held in South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe (1986).[138]

State statute of limitations do apply, however, for tribal actions under state law, such as quiet title, even if based on aboriginal title.[139] Similarly, the Supreme Court in 1907 declared that, for the sake of stability in property law, that it would defer to state court interpretations of Indian treaties.[140]

Laches

In Oneida II, the four dissenting justices would have applied laches to dismiss the claim.[81] Although the majority did not reach the issue (which the defendants had not preserved on appeal), it noted that "it is far from clear that this defense is available in suits such as this one" and that the "application of the equitable defense of laches in an action at law would be novel indeed."[81] A footnote in the majority also quoted Ewert v. Bluejacket (1922),[141] which held that laches "cannot properly have application to give vitality to a void deed and to bar the rights of Indian wards in lands subject to statutory restrictions."[81] City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. (2005) applied laches to an attempt to revive tribal sovereignty over land reacquired by the tribe in fee simple.[142]

Building on Sherrill, the Second Circuit in Cayuga Indian Nation of N.Y. v. Pataki (2005) held that "these equitable defenses apply to 'disruptive' Indian land claims more generally."[143] Although the Solicitor General joined the Cayugas' appeal,[144] the Supreme Court denied certiorari.[145] The Second Circuit has also applied laches to non-possessory contract claims for unconscionable consideration.[137] This doctrine has been criticized for not requiring the defendant to satisfy the traditional elements of the laches defense, applying only to Indian land claims, and having the potential to bar nearly all Indian land and treaty claims.[146]

No other Circuit has adopted the Second Circuit's expansive view of Sherrill. The Third, Sixth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits, since Sherrill, have declined to reach the question of the scope of laches as a defense to ancient tribal claims.[33][147][148][149][150] The First Circuit has limited Sherrill to assertions of sovereignty,[151] in an opinion that was reversed on other grounds.[152] Some district courts take the First Circuit's view;[153][154] others the Second Circuit's;[155][156][157] others strike a middle ground.[158]

Relationship to other rights

Aboriginal title is distinct from recognized Indian title, where the United States federal government recognizes tribal land by treaty or otherwise. Aboriginal title is not a prerequisite to recognized title.[159]

The relationship between aboriginal title and reservations is unclear.[160] Often, courts will not reach the question of aboriginal title, if the same land is found to comprise part of an Indian reservation.[126] Some reservations were created in a process that extinguished aboriginal title.[161] Although Congress has the power to grant tribes land in fee simple, some reservations may continue to be held in aboriginal title.[162]

The old view was that the extinguishment of aboriginal title extinguished all tribal rights to the same land.[163] The current view is that usufructuary rights pursuant to a treaty may survive the extinguishment of aboriginal title.[164] However, such usufructs may be lost when tribes cede land to the federal government.[165] Certain usufructs may be extinguished by implication.[166]

See also

Notes

- Banner, 2005, p. 180.

- Banner, 2005, p. 171--72, 179.

- Kades, 148 U. Pa. L. Rev. at 1092--93.

- Banner, 2005, p. 226.

- Banner, 2005, p. 235.

- Banner, 2005, p. 251.

- Banner, 2005, pp. 235--36.

- Banner, 2005, pp. 287--88.

- "Alaska History and Cultural Studies - Alaska's Cultures - ANCSA: What Political Process? - Paul Ongtooguk". Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- "How can AFN be the voice of Natives when its officers are not elected?". www.alaskool.org.

- Banner, 2005, p. 291.

- Confederated Tribes v. United States, 177 Ct. Cl. 184, 194 (1966).

- Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas v. U.S., 2000 WL 1013532 (Fed. Cl.).

- Strong v. United States, 207 Ct.Cl. 254 (1975).

- Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians v. U. S., 203 Ct.Cl. 426 (1974).

- Cramer v. United States, 261 U.S. 219 (1923).

- United States v. Lowry, 512 F.3d 1194 (9th Cir. 2008).

- United States v. Hensher, 1996 WL 539113 (9th Cir.) (unreported).

- City of Sherrill, N.Y. v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, 544 U.S. 197 (2005) ["Oneida III"].

- Cass County, Minn. v. Leech Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, 524 U.S. 103 (1998).

- Hagen v. Utah, 510 U.S. 399 (1994).

- U.S. v. Unzeuta, 281 U.S. 138 (1930).

- Alaska v. Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government, 522 U.S. 520 (1998).

- Aleut Community of St. Paul Island v. U. S., 202 Ct.Cl. 182 (1973).

- San Xavier Development Authority v. Charles, 237 F.3d 1149 (9th Cir. 2001).

- Johnson v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823).

- United States v. Santa Fe Pacific R. Co., 314 U.S. 339 (1941).

- Whitefoot v. U. S., 155 Ct.Cl. 127 (1961).

- Hale v. Gaines, 63 U.S. 144 (1859).

- Chouteau v. Molony, 57 U.S. 203 (1853).

- Thredgill v. Pintard, 53 U.S. 24 (1851).

- Clark v. Smith, 38 U.S. 195 (1839).

- Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania, 446 F.3d 410 (3rd Cir. 2006).

- Gila River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community v. U. S., 204 Ct.Cl. 137 (1974).

- U.S. v. Northern Paiute Nation, 203 Ct.Cl. 468 (1974).

- Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. Madison County, Oneida County, N.Y., 605 F.3d 149 (2d Cir. 2010).

- Seneca Nation of Indians v. New York, 382 F.3d 245 (2d Cir. 2004).

- Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. State of N.Y., 860 F.2d 1145 (2d Cir. 1988).

- Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903).

- Beecher v. Wetherby, 95 U.S. 517 (1877).

- United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371 (1905).

- Dubuque & S.C.R. Co. v. Des Moines Valley R. Co., 109 U.S. 329 (1883).

- Denn v. Reid, 35 U.S. 524 (1836).

- Oglala Sioux Tribe of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation v. Homestake Min. Co., 722 F.2d 1407 (8th Cir. 1983).

- United States v. Dann, 470 U.S. 39 (1985).

- Temoak Band of Western Shoshone Indians, Nevada v. U.S., 219 Ct.Cl. 346 (1979).

- Western Shoshone Nat. Council v. Molini, 951 F.2d 200 (9th Cir. 1991).

- Pueblo of Taos v. U.S., 231 Ct.Cl. 1051 (1982).

- United States v. Pend Oreille Public Utility Dist. No. 1, 926 F.2d 1502 (9th Cir. 1991).

- Western Shoshone Nat. Council v. U.S., 279 Fed.Appx. 980 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

- Devils Lake Sioux Tribe v. State of N.D., 917 F.2d 1049 (8th Cir. 1990).

- U. S. v. Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, 222 Ct.Cl. 1 (1979).

- Havasupai Tribe v. Robertson, 943 F.2d 32 (9th Cir. 1991).

- Greene v. Rhode Island, 398 F.3d 45 (1st Cir. 2005).

- Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370 (1st Cir. 1975).

- State v. Cameron, 658 A.2d 939, 940 (Vt. 1995) ("Our holding in that case was made as a matter of law based on historical fact. Consequently, under the doctrine of stare decisis, Elliott is precedent binding in general, not just binding on parties to the original case ...Elliott affects all lands within Vermont's boundaries."); State v. Elliott, 616 A.2d 210, 214 (Vt. 1992) ("[A] series of historical events, beginning with the Wentworth Grants of 1763, and ending with Vermont's admission to the Union in 1791, extinguished the aboriginal rights claimed here."); id. at 218 ("The legal standard does not require that extinguishment spring full blown from a single telling event. Extinguishment may be established by the increasing weight of history.").

- Gene Bergman, Defying Precedent: Can Abenaki Aboriginal Title Be Extinguished by the "Weight of History", 18 Am. Indian L. Rev. 447 (1993); John P. Lowndes, When History Outweighs Law: Extinguishment of Abenaki Aboriginal Title, 42 Buff. L. Rev. 77 (1994); Robert O. Lucido II, Aboriginal Title: The Abenaki Land Claim in Vermont, 16 Vt. L. Rev. 611 (1992); Joseph William Singer, Well Settled?: The Increasing Weight of History in American Indian Land Claims, 28 Ga. L. Rev. 481 (1994).

- Mohegan Tribe v. State of Conn., 638 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980).

- Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana v. Harry L. Laws Co., Inc., 490 F. Supp. 164 (W.D. La. 1980). aff'd, 690 F.2d 1157 (5th Cir. 1982).

- Act of March 2, 1805, 2 Stat. 324; Act of April 21, 1806, 2 Stat. 391; Act of March 3, 1807, 2 Stat. 440; Act of March 10, 1812, 2 Stat. 692; Act of April 14, 1812, 2 Stat. 709; Act of February 27, 1813, 2 Stat. 807; Act of April 18, 1814, 3 Stat. 139; Act of April 29, 1816, 3 Stat. 328; Act of May 11, 1820, 3 Stat. 573; Act of May 16, 1826, 4 Stat. 168; Act of May 26, 1824, 4 Stat. 52 (extended to Louisiana by Act of June 17, 1844, 5 Stat. 676).

- 9 Stat. 631.

- Byrne v. Alas, 16 P. 523, 528 (Cal. 1888).

- Super v. Work, 3 F.2d 90 (D.C. Cir.1925), aff'd, 271 U.S. 643 (1926) (per curiam); United States v. Title Insurance and Trust Co., 265 U.S. 472 (1924); Barker v. Harvey, 181 U.S. 481 (1901); United States ex rel. Chunie v. Ringrose, 788 F.2d 638 (9th Cir. 1986). See also Bruce S. Flushman & Joe Barbieri, Aboriginal Title: The Special Case of California, 17 Pac. L.J. 391 (1986).

- Inupiat Community of Arctic Slope v. U.S., 746 F.2d 570 (9th Cir. 1984).

- U.S. v. Atlantic Richfield Co., 612 F.2d 1132 (9th Cir. 1980).

- Inupiat Community of Arctic Slope v. United States, 230 Ct.Cl. 647 (1982).

- Amoco Production Co. v. Village of Gambell, AK, 480 U.S. 531 (1987).

- People of Village of Gambell v. Hodel, 869 F.2d 1273 (9th Cir.1989).

- People of Village of Gambell v. Clark, 746 F.2d 572 (9th Cir. 1984).

- Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981); State of Alaska v. Ahtna, Inc., 891 F.2d 1401 (9th Cir. 1989); Yankton Sioux Tribe of Indians v. State of S.D., 796 F.2d 241 (8th Cir. 1986).

- Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma, 397 U.S. 620 (1970); Muckleshoot Indian Tribe v. Trans-Canada Enterprises, Ltd., 713 F.2d 455 (9th Cir. 1983).

- Wilson v. Omaha Indian Tribe, 442 U.S. 653 (1979).

- United States v. Aranson, 696 F.2d 654 (9th Cir. 1983).

- Confederated Tribes of Colville Reservation v. U.S., 964 F.2d 1102 (Fed. Cir. 1992).

- Northern Mariana Islands v. United States, 399 F.3d 1057 (9th Cir. 2005).

- Native Village of Eyak v. Trawler Diane Marie, Inc.,154 F.3d 1090 (9th Cir. 1998).

- Government of Guam, ex rel. Guam Economic Development Authority v. United States, 179 F.3d 630 (9th Cir. 1999); see John Briscoe, The Aboriginal Land Title of the Native People of Guam, 26 Hawaii L. Rev. 1 (2003).

- Marsh v. Brooks, 49 U.S. 223 (1850) ("[T]hat an action of ejectment could be maintained on an Indian right to occupancy and use, is not open to question.").

- Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy, 162 U.S. 283 (1896).

- Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida County, 414 U.S. 661 (1974).

- Oneida County v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985).

- Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe of Indians v. Weicker, 39 F.3d 51 (2d Cir. 1994).

- Mashpee Tribe v. New Seabury Corp., 592 F.2d 575 (1st Cir 1979).

- Epps v. Andrus, 611 F.2d 915 (1st Cir. 1979).

- Mashpee Tribe v. Secretary of Interior, 820 F.2d 480 (1st Cir. 1987) (Breyer, J.).

- Sokaogon Chippewa Community v. State of Wis., Oneida County, 879 F.2d 300 (7th Cir.1989) .

- Fort Mojave Tribe v. Lafollette, 478 F.2d 1016 (9th Cir. 1973).

- Coy v. Mason, 58 U.S. 580 (1854).

- Cowlitz Tribe of Indians v. City of Tacoma, 253 F.2d 625 (9th Cir. 1958).

- Carino v. Insular Government of Philippine Islands, 212 U.S. 449 (1909).

- U.S. v. Shoshone Tribe of Indians of Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, 304 U.S. 111 (1938).

- U.S. v. Creek Nation, 295 U.S. 103 (1935).

- Northwestern Bands of Shoshone Indians v. United States, 324 U.S. 335 (1945).

- U.S. v. Klamath and Moadoc Tribes, 304 U.S. 119 (1938).

- Sioux Tribe of Indians v. U.S., 316 U.S. 317 (1942).

- Fort Berthold Reservation v. U. S., 182 Ct.Cl. 543 (1968).

- United States v. Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 329 U.S. 40 (1946) ["Tillamooks I"].

- Miller v. United States, 159 F.2d 997 (9th Cir. 1947).

- Hynes v. Grimes Packing Co., 337 U.S. 86 (1949) .

- United States v. Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 341 U.S. 48 (1951) ["Tillamooks II"].

- Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States, 348 U.S. 272 (1955).

- Karuk Tribe of California v. Ammon, 209 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2000).

- Seldovia Native Ass'n, Inc. v. U.S., 144 F.3d 769 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

- Zuni Indian Tribe of New Mexico v. U.S., 16 Cl.Ct. 670 (1989).

- U. S. v. Cherokee Nation, 200 Ct.Cl. 583 (1973).

- Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370 (1st 1975).

- Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wis. v. U. S., 165 Ct.Cl. 487 (1964).

- Cobell v. Norton, 240 F.3d 1081 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

- Shoshone Indian Tribe of Wind River Reservation v. U.S., 364 F.3d 1339 (Fed Cir. 2004).

- Yankton Sioux Tribe v. United States, 224 Ct.Cl. 62 (1980).

- Miami Tribe of Oklahoma v. U. S., 222 Ct.Cl. 242 (1980).

- U.S. v. Oneida Nation of New York, 217 Ct.Cl. (1978).

- Six Nations v. U. S., 173 Ct.Cl. 899 (1965).

- Coast Indian Community v. U. S., 213 Ct.Cl. 129 (1977).

- Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes of Flathead Reservation, Mont. v. U. S., 173 Ct.Cl. 398 (1965).

- Oglala Sioux Tribe of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation v. United States, 650 F.2d 140 (8th Cir. 1981).

- Caddo Tribe of Oklahoma v. U. S., 222 Ct.Cl. 306 (1980).

- Sac and Fox Tribe of Indians of Okl. v. U. S., 179 Ct.Cl. 8 (1967).

- U. S. v. Pueblo De Zia, 200 Ct.Cl. 601 (1973).

- U.S. v. Delaware Tribe of Indians, 192 Ct.Cl. 385 (1970).

- Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation, 362 U.S. 99, 120 (1960) ("[25 U.S.C. § 177] is not applicable to the sovereign United States ...").

- Kansas v. United States, 204 U.S. 331 (1907).

- Nichols v. Rysavy, 809 F.2d 1317 (8th Cir. 1987).

- Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Idaho, 521 U.S. 261 (1997).

- Idaho v. United States, 533 U.S. 262 (2001).

- Lauren E. Rosenblatt, Note, Removing the Eleventh Amendment Barrier: Defending Indian Land Title Against State Encroachment After Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe, 78 Tex. L. Rev. 719 (2000).

- Blatchford v. Native Vill. of Noatak, 501 U.S. 775 (1991).

- Timpanogos Tribe v. Conway, 286 F.3d 1195 (10th Cir. 2002).

- Western Mohegan Tribe and Nation v. Orange County, 395 F.3d 18 (2d Cir. 2004).

- 28 U.S.C. § 1362.

- Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo v. Laney, 199 F.3d 281 (5th Cir. 2000).

- Seminole Tribe of Fl. v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996).

- Alden v. Maine, 527 U.S. 706 (1999).

- United States v. Minnesota, 270 U.S. 181 (1926).

- Arizona v. California, 460 U.S. 605 (1983).

- Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. v. County of Oneida, 617 F.3d 114 (2d Cir. 2010).

- South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., 476 U.S. 498 (1986).

- Spirit Lake Tribe v. North Dakota, 262 F.3d 732 (8th Cir. 2001).

- Francis v. Francis, 203 U.S. 233 (1907) .

- Ewert v. Bluejacket, 259 U.S. 129 (1922).

- City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y., 544 U.S. 197 (2005).

- Cayuga Indian Nation of N.Y. v. Pataki, 413 F.3d 266 (2d Cir. 2005).

- 2006 WL 285801.

- 547 U.S. 1128 (2006).

- Kathryn E. Fort, The New Laches: Creating Title where None Existed, 16 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 357 (2009); Patrick W. Wandres, Indian Land Claims, Sherrill and the Impending Legacy of the Doctrine of Laches, 31 Am. Indian L. Rev. 131 (2006).

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma v. Logan, 577 F.3d 634 (6th Cir. 2009).

- Yankton Sioux Tribe v. Podhradsky, 606 F.3d 985 (8th Cir. 2008).

- Osage Nation v. Irby, 597 F.3d 1117 (10th Cir. 2010).

- Shawnee Tribe v. United States, 423 F.3d 1204 (10th Cir. 2005).

- Carcieri v. Norton, 423 F.3d 45 (1st Cir. 2005), reheard en banc, 497 F.3d 15 (1st Cir. 2007).

- 129 S.Ct. 1058 (2009).

- Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan v. Granholm, 2008 WL 4808823 (E.D. Mich. 2008).

- Paiute-Shoshone Indians of Bishop Community of Bishop Colony, California v. City of Los Angeles, 2007 WL 521403 (E.D. Cal. 2007).

- New Jersey Sand Hill Band of Lenape & Cherokee Indians v. Corzine, 2010 WL 2674565 (D. N.J. 2010).

- In re Schugg, 384 B.R. 263 (D. Ariz. 2008).

- Pelt v. Utah, 611 F.Supp.2d 1267 (D. Utah 2009).

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma v. Ohio Dept. of Natural Resources, 541 F.Supp.2d 971 (N.D. Ohio 2008).

- Sioux Tribe v. U. S., 205 Ct.Cl. 148 (1974).

- Bruce S. Flushman & Joe Barbieri, Aboriginal Title: The Special Case of California, 17 Pac. L.J. 391, 426 (1986) ("The effect of the establishment of a reservation on aboriginal title in ambiguous.").

- Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife v. Klamath Indian Tribe, 473 U.S. 753 (1985).

- U.S. v. Romaine, 255 F. 253 (9th Cir. 1919).

- Ward v. Race Horse, 163 U.S. 504 (1896).

- Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999); Menominee Tribe of Indians v. U.S., 391 U.S. 404 (1968); Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians v. Voigt, 700 F.2d 341 (7th Cir. 1983). But see In re Wilson, 634 P.2d 363 (Cal. 1983).

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians v. State of Minn., 614 F.2d 1161 (8th Cir. 1980).

- Confederated Tribes of Chehalis Indian Reservation v. State of Wash., 96 F.3d 334 (9th Cir. 1996).

References

- Stuart Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier (2005).

- Nancy Carol Carter, Race and Power Politics as Aspects of Federal Guardianship over American Indians: Land-Related Cases, 1887–1924, 4 Am. Indian L. Rev. 197 (1976).

- Robert N. Clinton & Margaret Tobey Hotopp, Judicial Enforcement of the Federal Restraints on Alienation of Indian Land: The Origins of the Eastern Land Claims, 31 Me. L. Rev. 17 (1979)

- Gus P. Coldebella & Mark S. Puzella, The Landowner Defendants in Indian Land Claims: Hostages to History, 37 New Eng. L. Rev. 585 (2003).

- George P. Generas, Jr & Karen Gantt, This Land is Your Land, This Land is My Land: Indian Land Claims, 28 J. Land Resources & Envtl. L. 1 (2008).

- Nell Jessup Newton, Indian Claims in the Courts of the Conqueror, 41 Am. Indian L. Rev. 753 (1992).

- Wenona T. Singel & Matthew L.M. Fletcher, Power, Authority & Tribal Property, 41 Tulsa L. Rev. 21 (2005).

- Tim Vollmann, A Survey of Eastern Indian Land Claims: 1970–1979, 31 Me. L. Rev. 5 (1979).

Further reading

- Russel L. Barsh, Indian Land Claims Policy in the United States, 58 N.D. L. Rev. 7 (1982).