Indoxyl sulfate

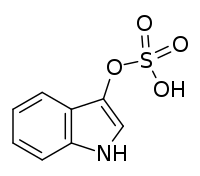

Indoxyl sulfate, also known as 3-indoxylsulfate and 3-indoxylsulfuric acid, is a metabolite of dietary L-tryptophan that acts as a cardiotoxin and uremic toxin.[1][2][3] High concentrations of indoxyl sulfate in blood plasma are known to be associated with the development and progression of chronic kidney disease and vascular disease in humans.[1][2][3] As a uremic toxin, it stimulates glomerular sclerosis and renal interstitial fibrosis.[1][2]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1H-Indol-3-yl hydrogen sulfate | |

| Other names

3-Indoxylsulfate; 3-Indoxylsulfuric acid; Indol-3-yl sulfate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H7NO4S | |

| Molar mass | 213.21 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Biosynthesis

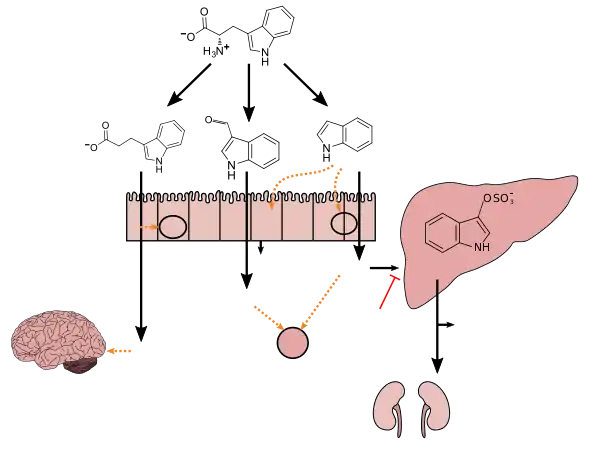

Indoxyl sulfate is a metabolite of dietary L-tryptophan that is synthesized through the following metabolic pathway:[3][4][5]

Indole is produced from L-tryptophan in the human intestine via tryptophanase-expressing gastrointestinal bacteria.[3] Indoxyl is produced from indole via enzyme-mediated hydroxylation in the liver;[3][4] in vitro experiments with rat and human liver microsomes suggest that the CYP450 enzyme CYP2E1 hydroxylates indole into indoxyl.[4] Subsequently, indoxyl is converted into indoxyl sulfate by sulfotransferase enzymes in the liver;[4][5] based upon in vitro experiments with recombinant human sulfotransferases, SULT1A1 appears to be the primary sulfotransferase enzyme involved in the conversion of indoxyl into indoxyl sulfate.[5]

Tryptophan metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota ()

|

Clinical significance

Occasionally in urinary tract infections, bacteria produce indoxyl phosphatase which splits indoxyl sulfate forming indigo and indirubin creating dramatic purple urine.[9] Indoxyl sulfate is also a product of indole metabolism, which is produced from tryptophan by intestinal flora, such as Escherichia coli.[10]

References

- Indoxyl sulfate. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Indoxyl sulfate. 11 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Zhang LS, Davies SS (April 2016). "Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions". Genome Med. 8 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x. PMC 4840492. PMID 27102537.

Lactobacillus spp. convert tryptophan to indole-3-aldehyde (I3A) through unidentified enzymes [125]. Clostridium sporogenes convert tryptophan to IPA [6], likely via a tryptophan deaminase. ... IPA also potently scavenges hydroxyl radicals

Table 2: Microbial metabolites: their synthesis, mechanisms of action, and effects on health and disease

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of action of indole and its metabolites on host physiology and disease - Banoglu E, Jha GG, King RS (2001). "Hepatic microsomal metabolism of indole to indoxyl, a precursor of indoxyl sulfate". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 26 (4): 235–40. doi:10.1007/bf03226377. PMC 2254176. PMID 11808865.

- Banoglu E, King RS (2002). "Sulfation of indoxyl by human and rat aryl (phenol) sulfotransferases to form indoxyl sulfate". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 27 (2): 135–40. doi:10.1007/bf03190428. PMC 2254172. PMID 12064372.

- Wikoff WR, Anfora AT, Liu J, Schultz PG, Lesley SA, Peters EC, Siuzdak G (March 2009). "Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (10): 3698–3703. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3698W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812874106. PMC 2656143. PMID 19234110.

Production of IPA was shown to be completely dependent on the presence of gut microflora and could be established by colonization with the bacterium Clostridium sporogenes.

IPA metabolism diagram - "3-Indolepropionic acid". Human Metabolome Database. University of Alberta. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Omar RA, Chain DG, Frangione B, Ghiso J, Pappolla MA (July 1999). "Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer beta-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (31): 21937–21942. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.31.21937. PMID 10419516. S2CID 6630247.

[Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA)] has previously been identified in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of humans, but its functions are not known. ... In kinetic competition experiments using free radical-trapping agents, the capacity of IPA to scavenge hydroxyl radicals exceeded that of melatonin, an indoleamine considered to be the most potent naturally occurring scavenger of free radicals. In contrast with other antioxidants, IPA was not converted to reactive intermediates with pro-oxidant activity.

- Tan, CK; Wu YP; Wu HY; Lai CC (August 2008). "Purple urine bag syndrome". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 179 (5): 491. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071604. PMC 2518199. PMID 18725621.

- Evenepoel, P; Meijers, BK; Bammens, BR; Verbeke, K (December 2009). "Uremic toxins originating from colonic microbial metabolism". Kidney International Supplements. 76 (114): S12-9. doi:10.1038/ki.2009.402. PMID 19946322.