Infrarealism

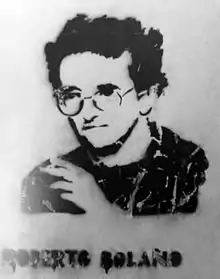

Infrarealism (Spanish: Infrarrealismo) is a poetic movement founded in Mexico City in 1975 by a group of twenty young poets, including Roberto Bolaño, Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, José Vicente Anaya, Rubén Medina and José Rosas Ribeyro.

The Infrarealists, also known as “infras”, took for their motto a phrase from the Chilean painter Roberto Matta: “Blow the brains out of the cultural establishment”.[1] Rather than a defined style, the movement was characterised by the pursuit of a free and personal poetry, representative of its members’ attitude towards life on the fringes of conventional society, in a similar manner to the Beat Generation of the 1950s.[2][3][4]

The origin of the phrase is French. The intellectual Emmanuel Berl attributes it to one of the founders of Surrealism, the writer and political activist Philippe Soupault (1897-1990), who was also one of the driving forces behind Dadaism.[5] According to Bolaño, however, the name was originally coined in the 1940s by Roberto Matta, after André Breton expelled him from the Surrealists. Cast out, Matta became an “Infrarealist”, and the only one up until the term's rebirth as a literary movement.[6][7] A third account for the name’s origin can be traced back to Russian writer Georgy Gurevich's sci-fi novella Infra Dragonis, originally published in 1959, and mentioned by Bolaño in the first Infrarealist manifesto.[8]

The initial phase of Infrarealism, its most important, lasted until the departure of Papasquiaro and Bolaño to Europe in 1977, who were the initiators and primary leaders of the movement.[9] However, on Papasquiario's return to Mexico City in 1979, the movement continued once more under his leadership until his death in 1998. At present, the movement is maintained by a mix of new and original members.[10]

History of the movement

In 1968, at a time when the future Infrarealist poets were still children and adolescents, the so-called Dirty War began to take shape in Mexico during the presidency of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (Institutional Revolutionary Party, 1964-1970). Amongst its principal consequences was the Tlatelolco Massacre in the Ciudad Universitaria of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where an estimated 300 to 400 students and civilians were murdered by military and police. The movie Roma, sheds light to the CIA involvement in the massacre. .Roberto Bolaño, 15-years-old, arrived in Mexico City from Chile with his family this same year.[11]

In 1970, Luis Echeverría Álvarez (Institutional Revolutionary Party, 1970-1976) took up presidency in Mexico. He was the ex-Secretariat of the Interior in the government of Díaz Ordaz, who was considered by the majority of the Mexican population as one of the principal culprits of the Dirty War.[12][13][14] To recapture Mexico’s youth, the new government set up a series of cultural scholarships, in addition to the creation of artistic and cultural workshops in universities and public institutions. Some of these were run by renowned writers such as Augusto Monterroso and Alejandro Aura. The Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the UNAM organised prose and poetry workshops and published the Punto de Partida magazine through the Department of Cultural Diffusion, which also ran prose, poetry, drama and essay workshops. Further workshops were held at the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM), courses run at the Casa del Lago cultural centre, and scholarships granted to study literature at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Institute of Fine Arts).[11]

Infrarealism emerged at the end of Luis Echeverría’s government in the midst of this effervescence of literary workshops in Mexico City, which were allowing many young people to begin to develop as poets and novelists.[11] Determined to create a new literary movement based on expressive freedom, the liveliness of language and the breaking of conventions. After fleeing from the 1973 events in Chile which saw Augusto Pinochet take power from Salvador Allende in a coup, Bolaño (a Chilean who had previously spent 5 years living in Mexico) met Santiago Papasquiaro in the Café La Habana in Mexico City, beginning a long friendship between the two which marked the beginning of infrarrealismo.[15] The movement was formally founded in Bruno Montané Krebs's house.[16] There were forty people at the meeting, which was led by Bolaño. Roberto Bolaño and Mario Santiago Papasquiaro began to meet with other friends and poets they considered fit for the project.[11]

Sabotages

According to the Chilean writer Carlos Chimal, president Luis Echeverría’s measures to promote cultural activity in the country polarised Mexico’s artistic society into “two worlds: high culture and popular culture, and there was no way that the two would touch”. The first of these worlds referred to artists who were granted scholarships or received benefits in some way from the Institutional Revolutionary Party's government – among them, for example, José Luis Cuevas and Fernando Benítz. For the Infrarealists, this group also included writers and intellectuals of world renown, such as Octavio Paz or Carlos Monsiváis, who, despite not needing Echeverría's direct support, cultivated a dedicated readership, ran important literary magazines, and also benefited from tax revenues. At the other extreme was the world of popular culture, which the Infrarealists associated with the left-wing revolution and was made up of artists that opposed the buying and selling of talent.[11] While members of the first group sought to identify themselves with Octavio Paz, members of the second were closer to the poet Efraín Huerta. The Mexican writer Carmen Boullosa, a contemporary of the Infrarealists, agrees that both groups were exclusive, and recalls that the only poets who traversed between the two groups were Juan Pascoe and Verónica Volkow, a friend of Bolaño and granddaughter of Trotsky.[17] Despite this, Boullosa maintains that the two groups were not entirely dissimilar.

Rather than for their own readings, the Infrarealists were known for their sabotaging of the readings, book launches, awards ceremonies and general literary activities of poets belonging to this world of “high culture”. The first of these sabotages took place prior to the movement’s foundation. Towards the end of 1973, Mario Santiago Papasquiaro and his friend Ramón Méndez attempted to throw Juan Bañuelos out of his own poetry workshop in the Department of Cultural Diffusion at UNAM by acquiring the signatures of participants; though in the end it was them who were thrown out.[2]

The Infrarealists planned these acts in meetings. They sabotaged the events of different writers, including Octavio Paz himself. At the beginning of 1976, they sabotaged a reading by David Huerta, son of Efraín Huerta. While they got along well with his father, they considered David a privileged author who was destined to succeed under the sheltered protection of his surname. Only Bolaño participated in Huerta’s sabotaging. He later distanced himself from these acts, though still asked friends for details after the acts were carried out.[18] Years later, Carmen Boullosa confessed to having been afraid the Infrarealists would sabotage the prize ceremony where she was to receive the Salvador Novo scholarship, awarded to those under 21, which Darío Galicia had also obtained the year before.[17]

Other poets began to both fear and hate them for these attitudes. They treated them as arrogant and disrespectful, and managed to isolate them from the established publications of the time.[19] In 1975, in the La cultura en México supplement of Siempre! magazine, edited by Carlos Monsiváis, a number of columns appeared in which a young Héctor Aguilar Camín, José Joaquin Blanco and Enrique Krauze spoke of a drop in standard in contemporary Mexican literature, which they viewed as resulting from socialist fashion, excessive sexuality and the appearance of so many new, novice writers. Blanco began to explicitly criticise the Infrarealists in these columns, and they confronted him directly, though this time with Bolaño in tow.[20]

Publications and separation

In mid-1976, after Octavio Paz left Plural magazine due to political problems in what became known as the "Excélsior coup”, Robert Rodríguez Baños was named as the magazine’s director and the Infrarealists once again had the opportunity to publish in established magazines. In October of the same year, in Plural number 61, Mario Santiago Papasquiaro published a review and translation of poems by the beat poet and novelist Richard Brautigan. Then, in December, in number 63, the magazine published Seis jóvenes infrarrealistas mexicanos (Six Young Mexican Infrarealists), with editing and introduction from Papasquairo and featuring Darío Galicia, Mara Larrosa, Rubén Medina, Cuauthémoc Méndez, José Peguero and Papasquairo himself. In January 1977, Roberto Bolaño was published in number 64.[3]

The Infrarealists also published their own anthology in 1976, Pájaro de calor, ocho poetas infrarrealistas (Bird of Heat, Eight Infrarealist Poets), which contained a prologue by the Spanish poet and journalist Juan Cervera Sanchís. Based in Mexico, he was a regular of Café La Habana, where Bolaño and Papasquiaro held their Infrarealist meetings, and sympathised with the youthful energy of the infras.[3]

Shortly before the publication of Pájaro de calor, and made clear in a poem of said publication, Bolaño’s girlfriend Lisa Johnson broke up with him. This was one of the main reasons for Bolaño’s departure to Barcelona,[3] where his mother had been living since leaving Mexico in the mid-1970s.[21] Before leaving, however, he reached an agreement with Editorial Extemporáneos to publish Muchachos desnudos bajo el arcoiris de fuego. Once jóvenes poetas latinoamericanos (Naked Boys Under the Rainbow of Fire. Eleven Young Latin American Poets), an anthology of poems featuring Luis Suardíaz, Hernán Lavín Cerda, Jorge Pimentel, Orlando Guillén, Beltrán Morales, Fernando Nieto Cadena, Julián Gómez, Enrique Verástegui, Mario Santiago Papasquairo, Bruno Montané and Bolaño himself. Published in July 1979, the book is prefaced by Miguel Donoso Pareja, contains a piece by Efraín Huerta, and was the first from that era of Infrarealists to be paid for entirely by the publisher, rather than themselves.[3]

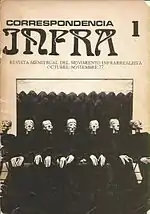

Roberto Bolaño left Mexico in 1977, shortly followed by Bruno Montané, whom he would meet up with again in Barcelona. Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, on the other hand, went to Paris and Israel for a while. Rubén Medina and José Peguero, trying to regroup the infras who had remained in Mexico City and at the same time as a symbolic act of farewell, managed the publication of a single issue of the magazine Correspondencia Infra in October/November of that year. The magazine had a circulation of five thousand copies, of which very few original copies remain, and includes the Manifiesto Infrarrealista (Infrarealist Manifesto), written by Bolaño, and a poem by Papasquiaro titled Consejos de un discípulo de Marx a un fanático de Heidegger (Advice from a disciple of Marx to a Heidegger fanatic). Written in the days when Papasquiaro frequented the Alejandro Aura’s workshop in Casa del Lago,[22] the poem served as inspiration for the title of the first novel by his friend Bolaño, now living in Spain: Consejos de un discípulo de Morrison a un fanático de Joyce (Advice from a disciple of Morrison to a Joyce fanatic), written in collaboration with A. G. Porta. The magazine’s poems were characterised by their stylistic variety.[3]

The following years

Various other Infrarealists decided to leave Mexico City in the years following the departure of Bolaño, Papasquiaro and Montané. Only some continued with literary careers, although the majority dedicated themselves to artistic activities. Rubén Medina went to study literature in the United States; Harrington returned to Chile to study film; Gelles Lebrija went to live in Tijuana; Piel Divina to Paris; the Méndez brothers returned to their hometown Morelia, where they worked in journalism, and for a time as bakers; José Vicente Anaya dedicated himself to travelling around Mexico for four years; Lorena de la Rocha chose classical music composition and theatre; and the Larrosa sisters stayed in Mexico City, with Vera devoting herself to dance and theatre,[3] and Mara to painting.[10]

Though the first phase of the movement ended with Bolaño and Papasquario’s departure to Europe in 1977, when Papasquario returned to Mexico City in 1979 he began to meet up with both old friends and new Infrarealists.[3] Between April 1980 and February 1981, poems from this new group of Infraealists appeared in three issues of Le Prosa magazine, edited by Orlando Guillén.[23] The sabotages also continued through the 80s, with Octavio Paz the victim of one in January 1980 at an event called the “Meeting of Generations” in the UNAM bookshop.[10]

Between November 1984 and July 1990, the Infrarealists published a poetry pamphlet titled Calandria de tolvaneras, which also included poems from older members like Roberto Bolaño and Bruno Montané. Between March 1992 and January 1993, various Infrarealists were published in several issues of Zonaeropuerto magazine, which was also edited by Orlando Guillén. In March 1992 they published the magazine La zorra vuelve al gallinero, with two further issues in 2000 and 2002.[24] The later issues, however, were without Papasquairo, who died in 1998.[10] A decade after his death, Mario Raúl Guzman and Rebeca López, Papasquario’s widow, published Jeta de santo. Antología poética 1974-1977, which compiled 161 of Papasquario’s poems.[25]

Bolaño undoubtedly achieved the greatest international prestige out of the older Infrarealists, establishing himself as a novelist in Barcelona and publishing numerous works for Editorial Anagrama. The standout successes of these publications were The Savage Detectives, a novel which won Spain’s Premio Herralde and was directly inspired by his life with the Infrarealists in Mexico City; and 2666, which won awards in Spain, Chile and the United States and was also set in Mexico.[3]

References

- Astorga, Antonio. "Volarle la tapa de los sesos a la cultura oficial es medida ciertamente saludable". ABC.es. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 47–63. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 83–100. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 29–44. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Herralde, Jorge. "Para Roberto Bolaño". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "María Teresa Cárdenas y Erwin Díaz: Revista de Libros de El Mercurio". Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Castañeda, Eva. "El infrarrealismo, subversión como propuesta estética". Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Ruiz, Felipe. "Infrarrealistas en Ciudad de México. Un recorrido: Bolaño y el país de los soles negros". Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "María Teresa Cárdenas y Erwin Díaz: Revista de Libros de El Mercurio". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 125–134. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 17–26. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Carmona, Doralicia. "Luís Echeverría Álvarez asume la presidencia de la República para el periodo 1970-1976". Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Parametría. "Juicio a Luis Echeverría Álvarez: movimientos sociales del 68 y 71". Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Castillo, Gustavo. "En la guerra sucia militares recibieron la orden de exterminar a guerrilleros". Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Madariaga, 2011, op. cit. pp. 125-134; chap. 8: «Después de la aventura».

- Roberto Careaga: La Tercera (28 November 2012). "Libro recrea la guerrilla mexicana de Bolaño". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Paz Soldán, Edmundo; Faverón Patriau, Gustavo, eds. (2013). Bolaño salvaje (2nd ed.). Avinyonet del Penedés, Barcelona: Editorial Candaya. pp. 434–446. ISBN 978-84-938903-8-4.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 65–81. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 65–81. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 65–81. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Madariaga, Monserrat (2010). Bolaño infra: 1975-1977. Los años que inspiraron 'Los detectives salvajes'. Santiago, Chile: RIL Editores. pp. 29–44. ISBN 978-956-284-763-6.

- Medina, Rubén (2014). Perros habitados por las voces del desierto. Poesía infrarrealista entre dos siglos. Mexico City: ALDVS. p. 47. ISBN 978-607-774-289-0.

- Movimiento Infrarrealista. "Le Prosa". Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Movimiento Infrarrealista. "Calandrias de tolvañeras". Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Livaria Cultura. "Jeta de santo. Antología poética 1974-1977". Retrieved 24 November 2017.