International Organization for Migration

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is a United Nations agency that provides services and advice concerning migration to governments and migrants, including internally displaced persons, refugees, and migrant workers.

| |

| Formation | 6 December 1951 |

|---|---|

| Type | UN Agency |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

Membership (2023) | 175 member states and 8 observer states |

Official languages | English, French and Spanish |

Director General | Amy Pope |

Revenue (2021) | US$2.5 billion |

Staff (2021) | 17,761 |

| Website | www |

The IOM was established in 1951 as the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) to help resettle people displaced by World War II. It became a United Nations agency in 2016.[1]

The IOM is the principal UN agency working in the field of migration. The IOM promotes humane and orderly migration by providing services and advice to governments and migrants.

The IOM works in the four broad areas of migration management: migration and development, facilitating migration, regulating migration, and addressing forced migration.

History

The IOM was born in 1951 out of the chaos and displacement of Western Europe following the Second World War. It was first known as the Provisional Intergovernmental Committee for the Movement of Migrants from Europe (PICMME). Mandated to help European governments to identify resettlement countries for the estimated 11 million people uprooted by the war, PICMME arranged transport for nearly a million migrants during the 1950s.

The Constitution of the International Organization for Migration was concluded on 19 October 1953 in Venice as the Constitution of the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration. The Constitution entered into force on 30 November 1954 and the organization was formally established.

The organization underwent a succession of name changes from PICMME to the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) in 1952, to the Intergovernmental Committee for Migration (ICM) in 1980, and finally, to its current name, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 1989; these changes reflect the organization's transition over half a century from an operational agency to a migration agency.

While the IOM's history tracks the man-made and natural disasters of the past half century—Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968, Chile 1973, the Vietnamese Boat People 1975, Kuwait 1990, Kosovo and Timor 1999, and the Asian tsunami, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Pakistan earthquake of 2004/2005, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and the ongoing European migrant crisis—its credo that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society has steadily gained international acceptance.

From its roots as an operational logistics agency, the IOM has broadened its scope to become the leading international agency working with governments and civil societies to advance the understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration, and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants.

The broader scope of activities has been matched by rapid expansion from a relatively small agency into one with an annual operating budget of US$1.8 billion and some 11,500 staff[2] working in over 150 countries worldwide.

As the "UN migration agency", the IOM has become a main point of reference in the heated global debate on the social, economic and political implications of migration in the 21st century.[3]

The IOM became a related organization of the United Nations in September 2016.[1]

The IOM supported the creation of the Global Compact for Migration, the first-ever intergovernmental agreement on international migration which was adopted in Marrakech, Morocco, in December 2018.[4] To support the implementation, follow-up and review of the Global Compact on Migration, The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, established the UN Network on Migration. The secretariat of the UN Network on Migration is housed at the IOM and the Director General of the IOM, Amy Pope, serves as the Network Coordinator.[5]

Activities

The IOM works to help ensure the orderly and humane management of migration, to promote international cooperation on migration issues, to assist in the search for practical solutions to migration problems and to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants in need, be they refugees, displaced persons or other uprooted people.

The IOM Constitution gives explicit recognition to the link between migration and economic, social and cultural development.[6][7]

The IOM works in the four broad areas of migration management: migration and development, facilitating migration, regulating migration, and addressing forced migration. Cross-cutting activities include the promotion of international migration law, policy debate and guidance, protection of migrants’ rights, migration health and the gender dimension of migration.

In addition, the IOM has often organized elections for refugees out of their home country, as was the case in the 2004 Afghan elections and the 2005 Iraqi elections.

For the 2009 EU-Anti-Trafficking Day, the Geneva Headquarters launched the Buy Responsibly awareness raising campaign to counter human trafficking. A year later, the campaign was introduced in the Netherlands and Austria, among other countries.[8][9]

IOM X

IOM X is a campaign operated by the International Organization for Migration in Bangkok that encourages safe migration and prevents exploitation and human trafficking in the Asia Pacific region.[10][11] The campaign addresses issues related to exploitation and human trafficking, such as protecting men enslaved in the Thai fishing industry,[12] the use of technology to identify and combat human trafficking,[13] and end the sexual exploitation of children.[14]

2003 Amnesty and Human Rights Watch

In 2003, both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch were critical of the IOM's role in the Australian government's "Pacific Solution" of transferring asylum seekers to offshore detention centres.[15][16] Human Rights Watch criticized the IOM for operating Manus Regional Processing Centre and the processing centre on Nauru despite not having a refugee protection mandate.[15] Human Rights Watch criticized the IOM for being part of "arbitrary detention" and for denying asylum seekers access to legal advice.[15] Human Rights Watch urged the IOM to cease operation the process centres, which it stated were "detention centres" and to hand management of the centres to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.[15]

Amnesty International expressed concern that the IOM undertook actions on behalf of governments that negatively impacted the human rights of asylum seekers, refugees and migrants.[16] Amnesty International cited an example of fourteen Kurds in Indonesia who were expelled from Australian waters by Australian authorities and relocated to Indonesia.[16] Amnesty International requested an assurance that the IOM will abide by the principle of non-refoulement.[17]

2022 Refugee Council of Australia

In 2022, the role that the IOM played in housing refugees in Indonesia was described by the Refugee Council of Australia as presenting a "humanitarian veneer while carrying out rights-violating activities on behalf of Western nations” by researchers Asher Hirsch and Cameron Doig in The Globe and Mail.[18]

The community housing that the IOM operated, using Australian government funding, was described by the Refugee Council of Australia "inhumane conditions, solitary confinement, lack of basic essentials and medical care, physical and sexual abuse, and severe overcrowding".[18] Rohingya John Joniad described the housing as an "open prison".[18]

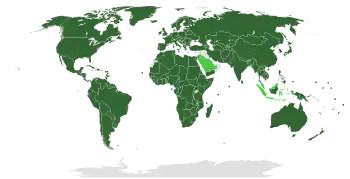

Member states

member

observer

non-members

As of 2023, the International Organization for Migration has 175 member states and 8 observer states.[19] Member states:

.svg.png.webp) Afghanistan

Afghanistan Albania

Albania Algeria

Algeria Angola

Angola Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Argentina

Argentina Armenia

Armenia.svg.png.webp) Australia

Australia Austria

Austria Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan Bahamas

Bahamas Bangladesh

Bangladesh Barbados

Barbados Belarus

Belarus.svg.png.webp) Belgium

Belgium Belize

Belize Benin

Benin.svg.png.webp) Bolivia

Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana

Botswana Brazil

Brazil Bulgaria

Bulgaria Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Burundi

Burundi Cabo Verde

Cabo Verde Cambodia

Cambodia Cameroon

Cameroon.svg.png.webp) Canada

Canada Central African Republic

Central African Republic Chad

Chad Chile

Chile China

China Colombia

Colombia Comoros

Comoros Congo

Congo Cook Islands

Cook Islands Costa Rica

Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire

Côte d'Ivoire Croatia

Croatia Cuba

Cuba Cyprus

Cyprus Czech Republic

Czech Republic Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo Denmark

Denmark Djibouti

Djibouti Dominica

Dominica Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Ecuador

Ecuador Egypt

Egypt El Salvador

El Salvador Eritrea

Eritrea Estonia

Estonia Eswatini

Eswatini Ethiopia

Ethiopia Fiji

Fiji Finland

Finland France

France Gabon

Gabon Gambia

Gambia Georgia

Georgia Germany

Germany Ghana

Ghana Greece

Greece Grenada

Grenada Guatemala

Guatemala Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Guyana

Guyana Haiti

Haiti.svg.png.webp) Holy See

Holy See Honduras

Honduras Hungary

Hungary Iceland

Iceland India

India Iran

Iran Ireland

Ireland Israel

Israel Italy

Italy Jamaica

Jamaica Japan

Japan Jordan

Jordan Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan Kenya

Kenya Kiribati

Kiribati Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan Lao People's Democratic Republic

Lao People's Democratic Republic Latvia

Latvia Lesotho

Lesotho Liberia

Liberia Libya

Libya Lithuania

Lithuania Luxembourg

Luxembourg Madagascar

Madagascar Malawi

Malawi Maldives

Maldives Mali

Mali Malta

Malta Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Mauritania

Mauritania Mauritius

Mauritius Mexico

Mexico Micronesia

Micronesia Mongolia

Mongolia Montenegro

Montenegro Morocco

Morocco Mozambique

Mozambique Myanmar

Myanmar Namibia

Namibia Nauru

Nauru Nepal

Nepal Netherlands

Netherlands New Zealand

New Zealand Nicaragua

Nicaragua Niger

Niger Nigeria

Nigeria North Macedonia

North Macedonia Norway

Norway Pakistan

Pakistan Palau

Palau Panama

Panama Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea Paraguay

Paraguay Peru

Peru Philippines

Philippines Poland

Poland Portugal

Portugal South Korea

South Korea Republic of Moldova

Republic of Moldova Romania

Romania Russian Federation

Russian Federation Rwanda

Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa

Samoa São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe Senegal

Senegal Serbia

Serbia Seychelles

Seychelles Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia

Slovenia Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands Somalia

Somalia South Africa

South Africa South Sudan

South Sudan Spain

Spain Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Sudan

Sudan Suriname

Suriname Sweden

Sweden.svg.png.webp) Switzerland

Switzerland Tajikistan

Tajikistan Thailand

Thailand Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Togo

Togo Tonga

Tonga Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia

Tunisia Turkey

Turkey Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Tuvalu

Tuvalu Uganda

Uganda Ukraine

Ukraine United Kingdom

United Kingdom United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania United States

United States Uruguay

Uruguay Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Vanuatu

Vanuatu Venezuela

Venezuela Viet Nam

Viet Nam Yemen

Yemen Zambia

Zambia Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Observer States:

Non-Member States:

See also

- Bibi Duaij Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, the IOM Goodwill Ambassador for Kuwait.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), also based (like the IOM) in Geneva.

Bibliography

- Andrijasevic, Rutvica; Walters, William (2010): The International Organization for Migration and the international government of borders. In Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6), pp. 977–999.

- Georgi, Fabian; Schatral, Susanne (2017): Towards a Critical Theory of Migration Control. The Case of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In Martin Geiger, Antoine Pécoud (Eds.): International organisations and the politics of migration: Routledge, pp. 193–221.

- Koch, Anne (2014): The Politics and Discourse of Migrant Return: The Role of UNHCR and IOM in the Governance of Return. In Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (6), pp. 905–923. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.855073.

References

- Megan Bradley (2017). "The International Organization for Migration (IOM): Gaining Power in the Forced Migration Regime". Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees. 33 (1): 97. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.40452.

- "109th Session of the Council, Report of the Director General" (PDF). GoverningBodies.iom.int. 30 November 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "History". International Organization for Migration. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "GCM Development Process". www.iom.int. International Organization for Migration. 9 April 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "Amy Pope Makes History as First Woman Director General of IOM". iom.int. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- "Constitution". International Organization for Migration. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), "Migration and Development: A Global Overview," 2009

- "IOM's Buy Responsibly Campaign Arrives in the Netherlands". International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- "Buy Responsibly Campaign | IOM Austria". austria.iom.int. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- "'Prisana' Film Aims to Raise Youth Awareness of Human Trafficking". Voice of America. Reuters. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Gender equality and female empowerment". ReliefWeb. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Hale, Erin (28 September 2016). "Tackling Asia's Human Trafficking with Facebook, WhatsApp and LINE". Forbes. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Vulcan Post". 21 December 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Hale, Erin (22 September 2016). "Philippine Cybersex 'Dens' are Making it Too Easy to Exploit Children". Forbes. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "The International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Human Rights Protection in the Field: Current Concerns (Submitted by Human Rights Watch, IOM Governing Council Meeting, 86th Session, November 18–21, 2003, Geneva)". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Amnesty International statement to the 86th Session of the Council of the International Organization for Migration (IOM)". Amnesty International. 20 November 2003. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Amnesty International (20 November 2003). "Statement to the 86th Session of the Council of the International Organization for Migration (IOM)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Griffiths, James (19 January 2022). "Trapped in Indonesia, Rohingya struggle to get by as laws block their path to asylum elsewhere". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Members and Observers" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2019.