Interpersonal communication

Interpersonal communication is an exchange of information between two or more people.[1] It is also an area of research that seeks to understand how humans use verbal and nonverbal cues to accomplish a number of personal and relational goals.[1]

Interpersonal communication research addresses at least six categories of inquiry: 1) how humans adjust and adapt their verbal communication and nonverbal communication during face-to-face communication; 2) how messages are produced; 3) how uncertainty influences behavior and information-management strategies; 4) deceptive communication; 5) relational dialectics; and 6) social interactions that are mediated by technology.[2]

A large number of scholars have described their work as research into interpersonal communication. There is considerable variety in how this area of study is conceptually and operationally defined.[3] Researchers in interpersonal communication come from many different research paradigms and theoretical traditions, adding to the complexity of the field.[4][5] Interpersonal communication is often defined as communication that takes place between people who are interdependent and have some knowledge of each other: for example, communication between a son and his father, an employer and an employee, two sisters, a teacher and a student, two lovers, two friends, and so on.

Although interpersonal communication is most often between pairs of individuals, it can also be extended to include small intimate groups such as the family. Interpersonal communication can take place in face-to-face settings, as well as through platforms such as social media.[6] The study of interpersonal communication addresses a variety of elements and uses both quantitative/social scientific methods and qualitative methods.

There is growing interest in biological and physiological perspectives on interpersonal communication. Some of the concepts explored are personality, knowledge structures and social interaction, language, nonverbal signals, emotional experience and expression, supportive communication, social networks and the life of relationships, influence, conflict, computer-mediated communication, interpersonal skills, interpersonal communication in the workplace, intercultural perspectives on interpersonal communication, escalation and de-escalation of romantic or platonic relationships, interpersonal communication and healthcare, family relationships, and communication across the life span.

Foundation of interpersonal communication

Interpersonal communication process principles

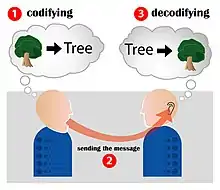

Human communication is a complex process with many components.[7] And there are principles of communication that guide our understanding of communication.

Communication is transactional

Communication is a transactional communication—that is, a dynamic process created by the participants through their interaction with each other.[8] In short, communication is an interactive process in which both parties need to participate. A metaphor is dancing. It is more like a process in which you and your partner are constantly running in and working together. Two perfect dancers do not necessarily guarantee the absolute success of a dance, but the perfect cooperation of two not-so-excellent dancers can guarantee a successful dance.

Communication can be intentional and unintentional

Some communication is intentional and deliberate, for example, before you ask your boss to give you a promotion or a raise, you will do a lot of mental building and practice many times how to talk to your boss so that it will not cause embarrassment. But at the same time, communication can also be unintentional. For example, you are complaining about your unfortunate experience today in the corner of the school, but it happens that your friend overhears your complaint. Even if you do not want others to know about your experience from the bottom of your heart, but unintentionally, this also delivers message and forms communication.

Communication Is Irreversible

The process of Interpersonal Communication is irreversible, you can wish you had not said something and you can apologise for something you said and later regret - but you can not take it back.[9]

Communication Is Unrepeatable

Unrepeatability arises from the fact that an act of communication can never be duplicated[10] The reason is that the audience may be different, our mood at the time may be different, or our relationship may be in a different place. In person communication can be invigorating and is often memorable when people are engaged and in the moment.

Theories

Uncertainty reduction theory

Uncertainty reduction theory, developed in 1975, comes from the socio-psychological perspective. It addresses the basic process of how we gain knowledge about other people. According to the theory, people have difficulty with uncertainty. You are not sure what is going to come next, so you are uncertain how you should prepare for the upcoming event.[11] To help predict behavior, they are motivated to seek information about the people with whom they interact.[12]

The theory argues that strangers, upon meeting, go through specific steps and checkpoints in order to reduce uncertainty about each other and form an idea of whether they like or dislike each other. During communication, individuals are making plans to accomplish their goals. At highly uncertain moments, they will become more vigilant and rely more on data available in the situation. A reduction in certainty leads to a loss of confidence in the initial plan, such that the individual may make contingency plans. The theory also says that higher levels of uncertainty create distance between people and that non-verbal expressiveness tends to help reduce uncertainty.[13]

Constructs include the level of uncertainty, the nature of the relationship and ways to reduce uncertainty. Underlying assumptions include the idea that an individual will cognitively process the existence of uncertainty and take steps to reduce it. The boundary conditions for this theory are that there must be some kind of trigger, usually based on the social situation, and internal cognitive process.

According to the theory, we reduce uncertainty in three ways:

- Passive strategies: observing the person.

- Active strategies: asking others about the person or looking up information

- Interactive strategies: asking questions, self-disclosure.

Uncertainty reduction theory is most applicable to the initial interaction context.[14] Scholars have extended the uncertainty framework with theories that describe uncertainty management and motivated information management.[15] These extended theories give a broader conceptualization of how uncertainty operates in interpersonal communication as well as how uncertainty motivates individuals to seek information. The theory has also been applied to romantic relationships.[16]

Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory falls under the symbolic interaction perspective. The theory describes, explains, and predicts when and why people reveal certain information about themselves to others. The social exchange theory uses Thibaut and Kelley's (1959) theory of interdependence. This theory states that "relationships grow, develop, deteriorate, and dissolve as a consequence of an unfolding social-exchange process, which may be conceived as a bartering of rewards and costs both between the partners and between members of the partnership and others".[17] Social exchange theory argues that the major force in interpersonal relationships is the satisfaction of both people's self-interest.[18]

According to the theory, human interaction is analogous to an economic transaction, in that an individual may seek to maximize rewards and minimize costs. Actions such as revealing information about oneself will occur when the cost-reward ratio is acceptable. As long as rewards continue to outweigh costs, a pair of individuals will become increasingly intimate by sharing more and more personal information. The constructs of this theory include disclosure, relational expectations, and perceived rewards or costs in the relationship. In the context of marriage, the rewards within the relationship include emotional security and sexual fulfillment.[19] Based on this theory Levinger argued that marriages will fail when the rewards of the relationship lessen, the barriers against leaving the spouse are weak, and the alternatives outside of the relationship are appealing.[13]

Symbolic interaction

Symbolic interaction comes from the socio-cultural perspective in that it relies on the creation of shared meaning through interactions with others. This theory focuses on the ways in which people form meaning and structure in society through interactions. People are motivated to act based on the meanings they assign to people, things, and events.[20]

Symbolic interaction considers the world to be made up of social objects that are named and have socially determined meanings. When people interact over time, they come to shared meaning for certain terms and actions and thus come to understand events in particular ways. There are three main concepts in this theory: society, self, and mind.

- Society

- Social acts (which create meaning) involve an initial gesture from one individual, a response to that gesture from another, and a result.

- Self

- Self-image comes from interaction with others. A person makes sense of the world and defines their "self" through social interactions that indicate the value of the self.

- Mind

- The ability to use significant symbols makes thinking possible. One defines objects in terms of how one might react to them.[13]

Constructs for this theory include creation of meaning, social norms, human interactions, and signs and symbols. An underlying assumption for this theory is that meaning and social reality are shaped from interactions with others and that some kind of shared meaning is reached. For this to be effective, there must be numerous people communicating and interacting and thus assigning meaning to situations or objects.

Relational dialectics theory

The dialectical approach to interpersonal communication revolves around the notions of contradiction, change, praxis, and totality, with influences from Hegel, Marx, and Bakhtin.[21][22] The dialectical approach searches for understanding by exploring the tension of opposing arguments. Both internal and external dialectics function in interpersonal relationships, including separateness vs. connection, novelty vs. predictability, and openness vs. closedness.[23]

Relational dialectics theory deals with how meaning emerges from the interplay of competing discourses.[24] A discourse is a system of meaning that helps us to understand the underlying sense of a particular utterance. Communication between two parties invokes multiple systems of meaning that are in tension with each other. Relational dialectics theory argues that these tensions are both inevitable and necessary.[24] The meanings intended in our conversations may be interpreted, understood, or misunderstood.[25] In this theory, all discourse, including internal discourse, has competing properties that relational dialectics theory aims to analyze.[22]

The three relational dialectics

Relational dialectics theory assumes three different types of tensions in relationships: connectedness vs. separateness, certainty vs. uncertainty, and openness vs. closedness. [26]

Connectedness vs. separateness

Most individuals naturally desire that their interpersonal relationships involve close connections. However, relational dialectics theory argues that no relationship can be enduring unless the individuals involved within it have opportunities to be alone. An excessive reliance on a specific relationship can result in the loss of individual identity.

Certainty vs. uncertainty

Individuals desire a sense of assurance and predictability in their interpersonal relationships. However, they also desire variety, spontaneity and mystery in their relationships. Like repetitive work, relationships that become bland and monotonous are undesirable.[27]

Openness vs. closedness

In close interpersonal relationships, individuals may feel a pressure to reveal personal information, as described in social penetration theory. This pressure may be opposed by a natural desire to retain some level of personal privacy.

Coordinated management of meaning

The coordinated management of meaning theory assumes that two individuals engaging in an interaction each construct their own interpretation and perception of what a conversation means, then negotiate a common meaning by coordinating with each other. This coordination involves the individuals establishing rules for creating and interpreting meaning.[28]

The rules that individuals can apply in any communicative situation include constitutive and regulative rules.

Constitutive rules are "rules of meaning used by communicators to interpret or understand an event or message".[28]

Regulative rules are "rules of action used to determine how to respond or behave".[28]

When one individual sends a message to the other the recipient must interpret the meaning of the interaction. Often, this can be done almost instantaneously because the interpretation rules that apply to the situation are immediate and simple. However, there are times when the interpretation of the 'rules' for an interaction is not obvious. This depends on each communicator's previous beliefs and perceptions within a given context and how they can apply these rules to the current interaction. These "rules" of meaning "are always chosen within a context",[28] and the context of a situation can be used as a framework for interpreting specific events. Contexts that an individual can refer to when interpreting a communicative event include the relationship context, the episode context, the self-concept context, and the archetype context.

- Relationship context

- This context assumes that there are mutual expectations between individuals who are members of a group.

- Episode context

- This context refers to a specific event in which the communicative act is taking place.

- Self-concept context

- This context involves one's sense of self, or an individual's personal 'definition' of him/herself.

- Archetype context

- This context is essentially one's image of what his or her belief consists of regarding general truths within communicative exchanges.

Pearce and Cronen[29] argue that these specific contexts exist in a hierarchical fashion. This theory assumes that the bottom level of this hierarchy consists of the communicative act. The relationship context is next in the hierarchy, then the episode context, followed by the self-concept context, and finally the archetype context.

Social penetration theory

Social penetration theory is a conceptual framework that describes the development of interpersonal relationships.[30] This theory refers to the reciprocity of behaviors between two people who are in the process of developing a relationship. These behaviors can include verbal/nonverbal exchange, interpersonal perceptions, and interactions with the environment. The behaviors vary based on the different levels of intimacy in the relationship.[31]

"Onion theory"

This theory is often known as the "onion theory". This analogy suggests that like an onion, personalities have "layers". The outside layer is what the public sees, and the core is one's private self. When a relationship begins to develop, the individuals in the relationship may undergo a process of self-disclosure,[32] progressing more deeply into the "layers".[33]

Social penetration theory recognizes five stages: orientation, exploratory affective exchange, affective exchange, stable exchange, and de-penetration. Not all of these stages happen in every relationship.[34]

- Orientation stage: strangers exchange only impersonal information and are very cautious in their interactions.

- Exploratory affective stage: communication styles become somewhat more friendly and relaxed.

- Affective exchange: there is a high amount of open communication between individuals. These relationships typically consist of close friends or even romantic or platonic partners.

- Stable exchange: continued open and personal types of interaction.[34]

- De-penetration: when the relationship's costs exceed its benefits there may be a withdrawal of information, ultimately leading to the end of the relationship.

If the early stages take place too quickly, this may be negative for the progress of the relationship.

- Example: Jenny and Justin met for the first time at a wedding. Within minutes Jenny starts to tell Justin about her terrible ex-boyfriend and the misery he put her through. This is information that is typically shared at stage three or four, not stage one. Justin finds this off-putting, reducing the chances of a future relationship.

Social penetration theory predicts that people decide to risk self-disclosure based on the costs and rewards of sharing information, which are affected by factors such as relational outcome, relational stability, and relational satisfaction.

The depth of penetration is the degree of intimacy a relationship has accomplished, measured relative to the stages above. Griffin defines depth as "the degree of disclosure in a specific area of an individual's life" and breadth as "the range of areas in an individual's life over which disclosure takes place."[33]

The theory explains the following key observations:

- Peripheral items are exchanged more frequently and sooner than private information;

- Self-disclosure is reciprocal, especially in the early stages of relationship development;

- Penetration is rapid at the start but slows down quickly as the tightly wrapped inner layers are reached;

- De-penetration is a gradual process of layer-by-layer withdrawal.[31]

Computer-mediated social penetration

Online communication seems to follow a different set of rules. Because much online communication occurs on an anonymous level, individuals have the freedom to forego the 'rules' of self disclosure. In on-line interactions personal information can be disclosed immediately and without the risk of excessive intimacy. For example, Facebook users post extensive personal information, pictures, information on hobbies, and messages. This may be due to the heightened level of perceived control within the context of the online communication medium.[35]

Relational patterns of interaction theory

Paul Watzlawick's theory of communication, popularly known as the "Interactional View", interprets relational patterns of interaction in the context of five "axioms".[36] The theory draws on the cybernetic tradition. Watzlawick, his mentor Gregory Bateson and the members of the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto were known as the Palo Alto Group. Their work was highly influential in laying the groundwork for family therapy and the study of relationships.[37]

Ubiquitous communication

The theory states that a person's presence alone results in them, consciously or not, expressing things about themselves and their relationships with others (i.e., communicating).[38] A person cannot avoid interacting, and even if they do, their avoidance may be read as a statement by others. This ubiquitous interaction leads to the establishment of "expectations" and "patterns" which are used to determine and explain relationship types.

Expectations

Individuals enter communication with others having established expectations for their own behavior as well as the behavior of those they are communicating with. During the interaction these expectations may be reinforced, or new expectations may be established that will be used in future interactions. New expectations are created by new patterns of interaction, while reinforcement results from the continuation of established patterns of interaction.

Patterns of interaction

Established patterns of interaction are created when a trend occurs regarding how two people interact with each other. There are two patterns of particular importance to the theory. In symmetrical relationships, the pattern of interaction is defined by two people responding to one another in the same way. This is a common pattern of interaction within power struggles. In complementary relationships, the participants respond to one another in opposing ways. An example of such a relationship would be when one person is argumentative while the other is quiet.

Relational control

Relational control refers to who is in control within a relationship. The pattern of behavior between partners over time, not any individual's behavior, defines the control within a relationship. Patterns of behavior involve individuals' responses to others' assertions.

There are three kinds of responses:

- One-down responses are submissive to, or accepting of, another's assertions.

- One-up responses are in opposition to, or counter, another's assertions.

- One-across responses are neutral in nature.

Complementary exchanges

A complementary exchange occurs when a partner asserts a one-up message which the other partner responds to with a one-down response. If complementary exchanges are frequent within a relationship it is likely that the relationship itself is complementary.

Symmetrical exchanges

Symmetrical exchanges occur when one partner's assertion is countered with a reflective response: a one-up assertion is met with a one-up response, or a one-down assertion is met with a one-down response. If symmetrical exchanges are frequent within a relationship it is likely that the relationship is also symmetrical.

Applications of relational control include analysis of family interactions,[36] and also the analysis of interactions such as those between teachers and students.[39]

Theory of intertype relationships

Socionics proposes a theory of relationships between psychological types (intertype relationships) based on a modified version of C.G. Jung's theory of psychological types. Communication between types is described using the concept of information metabolism proposed by Antoni Kępiński. Socionics defines 16 types of relations, ranging from the most attractive and comfortable to disputed. This analysis gives insight into some features of interpersonal relations, including aspects of psychological and sexual compatibility, and ranks as one of the four most popular models of personality.[40]

Identity management theory

Falling under the socio-cultural tradition, identity-management theory explains the establishment, development, and maintenance of identities within relationships, as well as changes to identities within relationships.[41]

Establishing identities

People establish their identities (or faces), and their partners, through a process referred to as "facework".[42] Everyone has a desired identity which they are constantly working towards establishing. This desired identity can be both threatened and supported by attempts to negotiate a relational identity (the identity one shares with one's partner). Thus, a person's desired identity is directly influenced by their relationships, and their relational identity by their desired individual identity.

Cultural influence

Identity management pays significant attention to intercultural relationships and how they affect the relational and individual identities of those involved, especially the different ways in which partners of different cultures negotiate with each other in an effort to satisfy desires for adequate autonomous identities and relational identities. Tensions within intercultural relationships can include stereotyping, or "identity freezing", and "nonsupport".

Relational stages of identity management

Identity management is an ongoing process that Imahori and Cupach define as having three relational stages.[41] The trial stage occurs at the beginning of an intercultural relationship when partners are beginning to explore their cultural differences. During this stage, each partner is attempting to determine what cultural identities they want in the relationship. At the trial stage, cultural differences are significant barriers to the relationship and it is critical for partners to avoid identity freezing and nonsupport. During this stage, individuals are more willing to risk face threats to establish a balance necessary for the relationship. The enmeshment stage occurs when a relational identity emerges with established common cultural features. During this stage, the couple becomes more comfortable with their collective identity and the relationship in general. In the renegotiation stage, couples work through identity issues and draw on their past relational history while doing so. A strong relational identity has been established by this stage and couples have mastered dealing with cultural differences. It is at this stage that cultural differences become part of the relationship rather than a tension within it.

Communication privacy management theory

Communication privacy management theory, from the socio-cultural tradition, is concerned with how people negotiate openness and privacy in relation to communicated information. This theory focuses on how people in relationships manage boundaries which separate the public from the private.[43]

Boundaries

An individual's private information is protected by the individual's boundaries. The permeability of these boundaries is ever changing, allowing selective access to certain pieces of information. This sharing occurs when the individual has weighed their need to share the information against their need to protect themselves. This risk assessment is used by couples when evaluating their relationship boundaries. The disclosure of private information to a partner may result in greater intimacy, but it may also result in the discloser becoming more vulnerable.

Co-ownership of information

When someone chooses to reveal private information to another person, they are making that person a co-owner of the information. Co-ownership comes with rules, responsibilities, and rights that must be negotiated between the discloser of the information and the receiver of it. The rules might cover questions such as: Can the information be disclosed? When can the information be disclosed? To whom can the information be disclosed? And how much of the information can be disclosed? The negotiation of these rules can be complex, and the rules can be explicit as well as implicit; rules may also be violated.

Boundary turbulence

What Petronio refers to as "boundary turbulence" occurs when rules are not mutually understood by co-owners, and when a co-owner of information deliberately violates the rules.[43] This is not uncommon and usually results in some kind of conflict. It often results in one party becoming more apprehensive about future revelations of information to the violator.

Cognitive dissonance theory

The theory of cognitive dissonance, part of the cybernetic tradition, argues that humans are consistency seekers and attempt to reduce their dissonance, or cognitive discomfort.[44] The theory was developed in the 1950s by Leon Festinger.[45]

The theory holds that when individuals encounter new information or new experiences, they categorize the information based on their preexisting attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs. If the new encounter does not fit their preexisting assumptions, then dissonance is likely to occur. Individuals are then motivated to reduce the dissonance they experience by avoiding situations that generate dissonance. For this reason, cognitive dissonance is considered a drive state that generates motivation to achieve consonance and reduce dissonance.

An example of cognitive dissonance would be if someone holds the belief that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is important, but maintains a sedentary lifestyle and eats unhealthy food. They may experience dissonance between their beliefs and their actions. If there is a significant amount of dissonance, they may be motivated to work out more or eat healthier foods. They may also be inclined to avoid situations that bring them face to face with the fact that their attitudes and beliefs are inconsistent, by avoiding the gym and avoiding stepping on their weighing scale.

To avoid dissonance, individuals may select their experiences in several ways: selective exposure, i.e. seeking only information that is consonant with one's current beliefs, thoughts, or actions; selective attention, i.e. paying attention only to information that is consonant with one's beliefs; selective interpretation, i.e. interpreting ambiguous information in a way that seems consistent with one's beliefs; and selective retention, i.e. remembering only information that is consistent with one's beliefs.

Types of cognitive relationships

According to cognitive dissonance theory, there are three types of cognitive relationships: consonant relationships, dissonant relationships, and irrelevant relationships. Consonant relationships are when two elements, such as beliefs and actions, are in equilibrium with each other or coincide. Dissonant relationships are when two elements are not in equilibrium and cause dissonance. In irrelevant relationships, the two elements do not possess a meaningful relationship with one another.

Attribution theory

Attribution theory is part of the socio-psychological tradition and analyzes how individuals make inferences about observed behavior. Attribution theory assumes that we make attributions, or social judgments, as a way to clarify or predict behavior.

Steps to the attribution process

- Observe the behavior or action.

- Make judgments about the intention of a particular action.

- Make an attribution of cause, which may be internal (i.e. the cause is related to the person), or external (i.e. the cause of the action is external circumstances).

For example, when a student fails a test an observer may choose to attribute that action to 'internal' causes, such as insufficient study, laziness, or having a poor work ethic. Alternatively the action might be attributed to 'external' factors such as the difficulty of the test, or real-world stressors that led to distraction.

Individuals also make attributions about their own behavior. The student who received a failing test score might make an internal attribution, such as "I just can't understand this material", or an external attribution, such as "this test was just too difficult."

Fundamental attribution error and actor-observer bias

Observers making attributions about the behavior of others may overemphasize internal attributions and underestimate external attributions; this is known as the fundamental attribution error. Conversely, when an individual makes an attribution about their own behavior they may overestimate external attributions and underestimate internal attributions. This is called actor-observer bias.

Expectancy violations theory

Expectancy violations theory is part of the socio-psychological tradition, and addresses the relationship between non-verbal message production and the interpretations people hold for those non-verbal behaviors. Individuals hold certain expectations for non-verbal behavior that are based on social norms, past experience and situational aspects of that behavior. When expectations are either met or violated, we make assumptions about the behaviors and judge them to be positive or negative.

Arousal

When a deviation of expectations occurs, there is an increased interest in the situation, also known as arousal. This may be either cognitive arousal, an increased mental awareness of expectancy deviations, or physical arousal, resulting in body actions and behaviors as a result of expectancy deviations.

Reward valence

When an expectation is not met, an individual may view the violation of expectations either positively or negatively, depending on their relationship to the violator and their feelings about the outcome.

Proxemics

One type of violation of expectations is the violation of the expectation of personal space. The study of proxemics focuses on the use of space to communicate. Edward T. Hall's (1940-2017) theory of personal space defined four zones that carry different messages in the U.S.:

- Intimate distance (0–18 inches). This is reserved for intimate relationships with significant others, or the parent-child relationship (hugging, cuddling, kisses, etc.)

- Personal distance (18–48 inches). This is appropriate for close friends and acquaintances, such as significant others and close friends, e.g. sitting close to a friend or family member on the couch.

- Social distance (4–10 feet). This is appropriate for new acquaintances and for professional situations, such as interviews and meetings.

- Public distance (10 feet or more). This is appropriate for a public setting, such as a public street or a park.

Pedagogical communication

Pedagogical communication is a form of interpersonal communication that involves both verbal and nonverbal components. A teacher's nonverbal immediacy, clarity, and socio-communicative style has significant consequences for students' affective and cognitive learning.[46]

It has been argued that "companionship" is a useful metaphor for the role of "immediacy", the perception of physical, emotional, or psychological proximity created by positive communicative behaviors, in pedagogy.[47]

Social networks

A social network is made up of a set of individuals (or organizations) and the links among them. For example, each individual may be treated as a node, and each connection due to friendship or other relationship is treated as a link. Links may be weighted by the content or frequency of interactions or the overall strength of the relationship. This treatment allows patterns or structures within the network to be identified and analyzed, and shifts the focus of interpersonal communication research from solely analyzing dyadic relationships to analyzing larger networks of connections among communicators.[48] Instead of describing the personalities and communication qualities of an individual, individuals are described in terms of their relative location within a larger social network structure. Such structures both create and reflect a wide range of social phenomena.

Hurt

Interpersonal communications can lead to hurt in relationships. Categories of hurt include devaluation, relational transgressions, and hurtful communication.

Devaluation

A person can feel devalued at the individual and relational level. Individuals can feel devalued when someone insults their intelligence, appearance, personality, or life decisions. At the relational level, individuals can feel devalued when they believe that their partner does not perceive the relationship to be close, important, or valuable.

Relational transgressions

Relational transgressions occur when individuals violate implicit or explicit relational rules. For instance, if the relationship is conducted on the assumption of sexual and emotional fidelity, violating this standard represents a relational transgression. Infidelity is a form of hurt that can have particularly strong negative effects on relationships. The method by which the infidelity is discovered influences the degree of hurt: witnessing the partner's infidelity first hand is most likely to destroy the relationship, while partners who confess on their own are most likely to be forgiven.[49]

Hurtful communication

Hurtful communication is communication that inflicts psychological pain. According to Vangelisti (1994), words "have the ability to hurt or harm in every bit as real a way as physical objects. A few ill-spoken words (e.g. "You're worthless", "You'll never amount to anything", "I don't love you anymore") can strongly affect individuals, interactions, and relationships."[50]

Interpersonal conflict

Many interpersonal communication scholars have sought to define and understand interpersonal conflict, using varied definitions of conflict. In 2004, Barki and Hartwick consolidated several definitions across the discipline and defined conflict as "a dynamic process that occurs between interdependent parties as they experience negative emotional reactions to perceived disagreements and interference with the attainment of their goals".[51] They note three properties generally associated with conflict situations: disagreement, negative emotion, and interference.

In the context of an organization, there are two targets of conflicts: tasks, or interpersonal relationships. Conflicts over events, plans, behaviors, etc. are task issues, while conflict in relationships involves dispute over issues such as attitudes, values, beliefs, behaviors, or relationship status.

Technology and interpersonal communication skills

Technologies such as email, text messaging and social media have added a new dimension to interpersonal communication. There are increasing claims that over-reliance on online communication affects the development of interpersonal communication skills,[52] in particular nonverbal communication.[53] Psychologists and communication experts argue that listening to and comprehending conversations plays a significant role in developing effective interpersonal communication skills.[54]

Others

- Attachment theory.[55] This theory follows the relationships that builds between a mother and child, and the impact it has on their relationships with others. It resulted from the combined work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991).

- Ethics in personal relations.[56] This considers a space of mutual responsibility between two individuals, including giving and receiving in a relationship. This theory is explored by Dawn J. Lipthrott in the article "What IS Relationship? What is Ethical Partnership?"

- Deception in communication.[57] This concept is based on the premise that everyone lies and considers how lying impacts relationships. James Hearn explores this theory in his article, "Interpersonal Deception Theory: Ten Lessons for Negotiators."

- Conflict in couples.[58] This focuses on the impact that social media has on relationships, as well as how to communicate through conflict. This theory is explored by Amanda Lenhart and Maeve Duggan in their paper, "Couples, the Internet, and Social Media."

Relevance to mass communication

Interpersonal communication has been studied as a mediator for information flow from mass media to the wider population. The two-step flow of communication theory proposes that most people form their opinions under the influence of opinion leaders, who in turn are influenced by the mass media. Many studies have repeated this logic in investigating the effects of personal and mass communication, for example in election campaigns[59] and health-related information campaigns.[60][61]

It is not clear whether or how social networking through sites such as Facebook changes this picture. Social networking is conducted over electronic devices with no face-to-face interaction, resulting in an inability to access the behavior of the communicator and the nonverbal signals that facilitate communication.[62] Side effects of using these technologies for communication may not always be apparent to the individual user, and may involve both benefits and risks.[63][64]

Context

Context refers to environmental factors that influence the outcomes of communication. These include time and place, as well as factors like family relationships, gender, culture, personal interest and the environment.[65] Any given situation may involve many interacting contexts,[66] including the retrospective context and the emergent context. The retrospective context is everything that comes before a particular behavior that might help understand and interpret that behavior, while the emergent context refers to relevant events that come after the behavior.[67] Context can include all aspects of social channels and situational milieu, the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of the participants, and the developmental stage or maturity of the participants.

Situational milieu

Situational milieu can be defined as the combination of the social and physical environments in which something takes place. For example, a classroom, a military conflict, a supermarket checkout, and a hospital would be considered situational milieus. The season, weather, current physical location and environment are also milieus.

To understand the meaning of what is being communicated, context must be considered.[68] Internal and external noise can have a profound effect on interpersonal communication. External noise consists of outside influences that distract from the communication.[69] Internal noise is described as cognitive causes of interference in a communication transaction.[69] In the hospital setting, for example, external noise can include the sound made by medical equipment or conversations had by team members outside of patient's rooms, and internal noise could be a health care professional's thoughts about other issues that distract them from the current conversation with a client.[70]

Channels of communication also affect the effectiveness of interpersonal communication. Communication channels may be either synchronous or asynchronous. Synchronous communication takes place in real time, for example face-to-face discussions and telephone conversations. Asynchronous communications can be sent and received at different times, as with text messages and e-mails.

In a hospital environment, for example, urgent situations may require the immediacy of communication through synchronous channels. Benefits of synchronous communication include immediate message delivery, and fewer chances of misunderstandings and miscommunications. A disadvantage of synchronous communication is that it can be difficult to retain, recall, and organize the information that has been given in a verbal message, especially when copious amounts of data have been communicated in a short amount of time. Asynchronous messages can serve as reminders of what has been done and what needs to be done, which can prove beneficial in a fast-paced health care setting. However, the sender does not know when the other person will receive the message. When used appropriately, synchronous and asynchronous communication channels are both efficient ways to communicate.[71] Mistakes in hospital contexts are often a result of communication problems.[72][73]

Cultural and linguistic backgrounds

Linguistics is the study of language, and is divided into three broad aspects: the form of language, the meaning of language, and the context or function of language. Form refers to the words and sounds of language and how the words are used to make sentences. Meaning focuses on the significance of the words and sentences that human beings have put together. Function, or context, interprets the meaning of the words and sentences being said to understand why a person is communicating.[74]

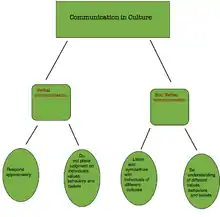

Culture is a human concept that encompasses the beliefs, values, attitudes, and customs of groups of people.[75] It is important in communication because of the help it provides in transmitting complex ideas, feelings, and specific situations from one person to another.[76] Culture influences an individual's thoughts, feelings and actions, and therefore affects communication.[77] The more difference there is between the cultural backgrounds of two people, the more different their styles of communication will be.[65] Therefore, it is important to be aware of a person's background, ideas and beliefs and consider their social, economic and political positions before attempting to decode the message accurately and respond appropriately.[78][79] Five major elements related to culture affect the communication process:[80]

Communication between cultures may occur through verbal communication or nonverbal communication. Culture influences verbal communication in a variety of ways, particularly by imposing language barriers.[81] Each individual has their own languages, beliefs and values that must be considered.[65] Factors influencing nonverbal communication include the different roles of eye contact in different cultures.[65] Touching as a form of greeting may be perceived as impolite in some cultures, but normal in others.[80] Acknowledging and understanding these cultural differences improves communication.[82]

In the health professions, communication is an important part of the quality of care and strongly influences client and resident satisfaction; it is a core element of care and is a fundamentally required skill.[76] For example, the nurse-patient relationship is mediated by both verbal and nonverbal communication, and both aspects need to be understood.

Developmental Progress (maturity)

Communication skills develop throughout one's lifetime. The majority of language development happens during infancy and early childhood. The attributes for each level of development can be used to improve communication with individuals of these ages.[83]

See also

| Library resources about Interpersonal communication |

References

- Berger, Charles R. (2008). "Interpersonal communication". In Wolfgang Donsbach (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Communication. New York, New York: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 3671–3682. ISBN 978-1-4051-3199-5.

- Berger, Charles R. (2005-09-01). "Interpersonal communication: Theoretical perspectives, future prospects". Journal of Communication. 55 (3): 415–447. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02680.x. ISSN 1460-2466.

- Knapp & Daly, 2011)

- Bylund, Carma L.; Peterson, Emily B.; Cameron, Kenzie A. (2012). "A practitioner's guide to interpersonal communication theory: An overview and exploration of selected theories". Patient Education and Counseling. 87 (3): 261–267. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.006. ISSN 0738-3991. PMC 3297682. PMID 22112396.

- Manning, J. (2014). "A Constitutive Approach to Interpersonal Communication Studies". Communication Studies. 65 (4): 432–440. doi:10.1080/10510974.2014.927294. S2CID 144637097.

- "Foundations of interpersonal communication (from Part I: Preliminaries to Interpersonal Messages)" (PDF). Interpersonal Messages. Pearson. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2015.

- Westerik, Henk (January 2009). "Adler, R. B. and Rodman, G. R. (2009). Understanding human communication (10th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press". Communications. 34 (1): 103–104. doi:10.1515/comm.2009.007. hdl:2066/77153. ISSN 0341-2059. S2CID 143410862.

- Westerik, Henk (January 2009). "Adler, R. B. and Rodman, G. R. (2009). Understanding human communication (10th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press". Communications. 34 (1): 103–104. doi:10.1515/comm.2009.007. hdl:2066/77153. ISSN 0341-2059. S2CID 143410862.

- "Principles of Interpersonal Communication | SkillsYouNeed". www.skillsyouneed.com. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Understanding and Enhancing Interpersonal Communication". Explore Our Extensive Counselling Article Library. 2016-06-07. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Iowa State University Digital Repository". lib.dr.iastate.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- Berger, C. R.; Calabrese, R. J. (1975). "Some Exploration in Initial Interaction and Beyond: Toward a Developmental Theory of Communication". Human Communication Research. 1 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00258.x. S2CID 144506084.

- Foss, K. & Littlejohn, S. (2008). Theories of Human Communication, Ninth Edition. Belmont, CA.

- Redmond, Mark (2015-01-01). "Uncertainty Reduction Theory". English Technical Reports and White Papers.

- BERGER, CHARLES R. (September 1986). "Uncertain Outcome Values in Predicted Relationships Uncertainty Reduction Theory Then and Now". Human Communication Research. 13 (1): 34–38. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1986.tb00093.x. ISSN 0360-3989.

- PARKS, MALCOLM R.; ADELMAN, MARA B. (September 1983). "COMMUNICATION NETWORKS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS An Expansion Of Uncertainty Reduction Theory". Human Communication Research. 10 (1): 55–79. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1983.tb00004.x. ISSN 0360-3989.

- Burgess, Robert L. (2013). Social Exchange in Developing Relationships. Huston, Ted L. Burlington: Elsevier Science. p. 4. ISBN 9781483261300. OCLC 897642908.

- Homans, George C. (1958). "Social Behavior as Exchange". American Journal of Sociology. 63 (6): 597–606. doi:10.1086/222355. S2CID 145134536.

- Levinger, George (1965). "Marital Cohesiveness and Dissolution: An Integrative Review". Journal of Marriage and Family. 27 (1): 19–28. doi:10.2307/349801. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 349801.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baxter, Leslie A. (2004-10-01). "A Tale of Two Voices: Relational Dialectics Theory". Journal of Family Communication. 4 (3–4): 181–192. doi:10.1080/15267431.2004.9670130. ISSN 1526-7431. S2CID 15370132.

- Baxter, Leslie A.; Montgomery, Barbara M. (1996-05-17). Relating: Dialogues and Dialectics. Guilford Press. ISBN 9781572301016.

- Montgomery, Barbara M.; Baxter, Leslie A. (2013-09-13). Dialectical Approaches to Studying Personal Relationships. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781135452063.

- Baxter, Leslie A.; Braithwaite, Dawn O. (2008), "Relational Dialectics Theory: Crafting Meaning from Competing Discourses", Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives, SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 349–362, doi:10.4135/9781483329529, ISBN 9781412938525, retrieved 2019-09-04

- Anderson, Rob; Baxter, Leslie A.; Cissna, Kenneth N. (2004). Dialogue: Theorizing Difference in Communication Studies. SAGE. ISBN 9780761926702.

- Baxter, Leslie (March 2004). "Relationships as Dialogues". Personal Relationships. 11 (1): 8. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00068.x. ISSN 1350-4126.

- Thackray, R. I. (1981). "The stress of boredom and monotony: a consideration of the evidence". Psychosomatic Medicine. 43 (2): 165–176. doi:10.1097/00006842-198104000-00008. ISSN 0033-3174. PMID 7267937. S2CID 22333772.

- Littlejohn, S. (1996). Theories of human communication (Ed 5). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

- Pearce, W. Barnett. (1980). Communication, action, and meaning : the creation of social realities. Cronen, Vernon E. New York, N.Y.: Praeger. ISBN 0275905349. OCLC 6735774.

- Altman, Irwin; Taylor, Dalmas A. (1973). Social penetration: the development of interpersonal relationships. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0030766354. OCLC 623272.

- Altman, Irwin; Taylor, Dalmas A. (1973). Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships, New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, p. 3, ISBN 978-0030766350

- Baack, Donald; Fogliasso, Christine; Harris, James (2000). "The Personal Impact of Ethical Decisions: A Social Penetration Theory". Journal of Business Ethics. 24 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1023/a:1006016113319. S2CID 142611191.

- Griffin, E. (2012). A First Look at Communication Theory (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 115-117, ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5

- Mongeau, P., and M. Henningsen. "Stage theories of relationship development." Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives (2008): 363-375.

- Ledbetter, Andrew M.; Mazer, Joseph P.; DeGroot, Jocelyn M.; Meyer, Kevin R.; Yuping Mao; Swafford, Brian (2010-09-10). "Attitudes Toward Online Social Connection and Self-Disclosure as Predictors of Facebook Communication and Relational Closeness". Communication Research. 38 (1): 27–53. doi:10.1177/0093650210365537. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 42955338.

- Watzlawick, Paul (2014). Pragmatics of human communication : a study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes. Bavelas, Janet Beavin, Jackson, Don D. (First published as a Norton paperback 2011, reissued 2014 ed.). New York. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9780393710595. OCLC 881386568.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - PROPAGATIONS : thirty years of influence from the mental research institute. ROUTLEDGE. 2016. ISBN 978-1138983984. OCLC 1009245842.

- Beavin, J (1990). "Behaving and communicating: a reply to Motley". Western Journal of Speech Communication. 54 (4): 593–602. doi:10.1080/10570319009374362.

- Weiss, Seth D.; Houser, Marian L. (2007-07-30). "Student Communication Motives and Interpersonal Attraction Toward Instructor". Communication Research Reports. 24 (3): 215–224. doi:10.1080/08824090701439091. ISSN 0882-4096. S2CID 144186728.

- Fink, Gerhard; Mayrhofer, Wolfgang (2009). "Cross-cultural competence and management – setting the stage". European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management. 1 (1): 42. doi:10.1504/EJCCM.2009.026733. ISSN 1758-1508. S2CID 53391171.

- Imahori, T. & Cupach, W. (1993). Identity management theory: communication competence in intercultural episodes and relationships. In Wiseman, R. L. & Koester, J., (Eds.), Intercultural Communication Competence (pp. 112 – 31). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Domenici, Kathy. (2006). Facework : bridging theory and practice. Littlejohn, Stephen W. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. ISBN 9781452222578. OCLC 804858912.

- Petronio, Sandra Sporbert. (2002). Boundaries of privacy : dialectics of disclosure. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0585492468. OCLC 54481653.

- Festinger, Leon, 1919-1989 (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, California. ISBN 0804709114. OCLC 921356.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Donsbach, Wolfgang (2008). Cognitive Dissonance Theory. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Donsbach, Wolfgang (ed). Blackwell Publishing.

- McCroskey, Linda; Richmond, Virginia; McCroskey, James (2002-10-01). "The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Contributions from the Discipline of Communication". Communication Education. 51 (4): 383–391. doi:10.1080/03634520216521. ISSN 0363-4523. S2CID 143506740.

- Sibii, Razvan (2010). "Conceptualizing teacher immediacy through the 'companion' metaphor". Teaching in Higher Education. 15 (5): 531–542. doi:10.1080/13562517.2010.491908. ISSN 1356-2517. S2CID 145527656.

- Parks, Malcolm R. (2011-08-26). Social Networks and the Life of Relationships. In The SAGE Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Knapp, Mark L. and Daly, John A. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781506318950.

- Afifi, Walid A.; Falato, Wendy L.; Weiner, Judith L. (2001). "Identity Concerns Following a Severe Relational Transgression: The Role of Discovery Method for the Relational Outcomes of Infidelity". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 18 (2): 291–308. doi:10.1177/0265407501182007. ISSN 0265-4075. S2CID 145723384.

- Vangelisti, Anita L. (1994). Messages that hurt: In "The dark side of interpersonal communication" eds. Cupach, William R., Spitzberg, Brian H. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. ISBN 0805811672. OCLC 28506031.

- Barki, Henri; Hartwick, Jon (2004). "Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict". International Journal of Conflict Management. 15 (3): 216–244. doi:10.1108/eb022913. ISSN 1044-4068. S2CID 18250620.

- Johnson, Chandra (2014-08-29). "Face time vs. screen time: The technological impact on communication". Deseret News. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Tardanico, Susan. "Is Social Media Sabotaging Real Communication?". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Robinson, Lawrence; Segal, Jeanne; Smith, Melinda (2015-09-18). "Improving Communication Skills in Your Work and Personal Relationships". PDResources. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Bretherton, I., (1992) The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, Developmental Psychology, 28, 759-775

- Lipthrott, D., What IS Relationship? What is Ethical Partnership?

- Hearn, J., (2006) Interpersonal Deception Theory: Ten Lessons for Negotiators

- Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., (2014) Couples, the Internet, and Social Media

- Farrell, David M.; Schmitt-Beck, Rüdiger (2002). Do political campaigns matter? Campaign effects in elections and referendums. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415255937. OCLC 49395522.

- Valente, T. W.; Poppe, P. R.; Merritt, A. P. (1996). "Mass-media-generated interpersonal communication as sources of information about family planning". Journal of Health Communication. 1 (3): 247–265. doi:10.1080/108107396128040. ISSN 1081-0730. PMID 10947363.

- Jeong, Michelle; Bae, Rosie Eungyuhl (2018). "The Effect of Campaign-Generated Interpersonal Communication on Campaign-Targeted Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis". Health Communication. 33 (8): 988–1003. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1331184. ISSN 1532-7027. PMID 28622003. S2CID 21446721.

- Drussell, John (2012-05-01). "Social Networking and Interpersonal Communication and Conflict Resolution Skills among College Freshmen". Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers.

- Greenfield, Patricia; Yan, Zheng (2006). "Children, adolescents, and the Internet: A new field of inquiry in developmental psychology". Developmental Psychology. 42 (3): 391–394. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.391. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 16756431.

- Berson, Ilene R.; Berson, Michael J.; Ferron, John M. (2002). "Emerging Risks of Violence in the Digital Age: Lessons for Educators from an Online Study of Adolescent Girls in the United States". Journal of School Violence. 1 (2): 51–71. doi:10.1300/J202v01n02_04. ISSN 1538-8220. S2CID 144349494.

- Corbin, C. White, D. (2008). "Interpersonal Communication: A Cultural Approach." Sydney, NS. Cape Breton University Press

- McHugh Schuste, Pamela (2010). Communication for Nursing: How to Prevent Harmful Events and Promote Patient Safety. USA: F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 9780803625303.

- Knapp, Mark L.; Daly, John A. (2002). Handbook of interpersonal communication (3. ed.). Thousand Oaks, Ca. [u.a.]: Sage Publ. ISBN 978-0-7619-2160-8.

- Knapp, M.L.; Daly, J.A.; Albada, K.F.; Miller, G.R. (2002). Handbook of interpersonal communication (3. ed.). Thousand Oaks, Ca. [u.a.]: Sage Publ. pp. 2–21. ISBN 978-0-7619-2160-8.

- Adler, R.B., Rosenfeld, L.B., Proctor II, R.F., Winder, C. (2012). ocess of Interpersonal Communication. Don Mills: Oxford University Press

- Costa, G.L.; Lacerda, A.B.; Marques, J. (2013). "Noise on the hospital setting: impact on nursing professionals' health". EFAC. 15 (3): 642–652.

- Parker, Julie; Coiera, Enrico (2000). "Improving Clinical Communication A View From Psychology". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 7 (5): 453–461. doi:10.1136/jamia.2000.0070453. PMC 79040. PMID 10984464.

- Thompson, T.L.; Parrott, R. (2002). Handbook of interpersonal communication (3. ed.). Thousand Oaks, Ca. [u.a.]: Sage Publ. pp. 680–725. ISBN 978-0-7619-2160-8.

- Kron, Thora (1972). Communication in nursing (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-5521-5.

- Monaghan, L. Goodman, J.E. (2007). A Cultural Approach to Interpersonal Communication. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Samovar, L.A. Porter, R.E. McDaniel, E.R. (2009). Communication Between Cultures. Boston, MA: Wadsworth CENGAGE Learning.

- Fleischer, S.; Berg, A.; Zimmermann, M.; Wüste, K.; Behrens, J. (2009). "Nurse-patient interaction and communication: A systematic literature review". Journal of Public Health. 17 (5): 339–353. doi:10.1007/s10389-008-0238-1. S2CID 40220721.

- Intercultural communication: A contextual approach (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage

- Smith, L. S. (2014). "Reaching for cultural competence". Plastic Surgical Nursing. 34 (3): 120–126. doi:10.1097/PSN.0000000000000059. PMID 25188850.

- Bourque Bearskin, R. L. (2011). "A critical lens on culture in nursing practice". Nursing Ethics. 18 (4): 548–559. doi:10.1177/0969733011408048. PMID 21673120.

- Samovar, L. A., Porter, R. E., & McDaniel, E. R. (2010). Communication between cultures. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, c2010

- Neuliep, J. (2009). Intercultural communication: A contextual approach (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage

- Muñoz, C. C., & Luckmann, J. (2005). Transcultural communication in nursing. Clifton Park, NY : Thomson/Delmar Learning, c2005.

- Reilly, Abigail Peterson (1980). The Communication Game. United States of America: Johnson & Johnson Baby Products Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-931562-05-1.

Bibliography

- Altman, Irwin; Taylor, Dalmas A. (1973). Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships, New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, p. 3, ISBN 978-0030766350

- Baack, Donald; Fogliasso, Christine; Harris, James (2000). "The Personal Impact of Ethical Decisions: A Social Penetration Theory". Journal of Business Ethics. 24 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1023/a:1006016113319. S2CID 142611191.

- Floyd, Kory. (2009). Interpersonal Communication: The Whole Story, New York: McGraw-Hill. (bibliographical information)

- Griffin, E. (2012). A First Look at Communication Theory (9th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 115–117, ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of Interpersonal Relations. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Mongeau, P., and M. Henningsen. "Stage theories of relationship development." Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives (2008): 363–375.

- Pearce, Barnett. Making Social Worlds: A Communication Perspective, Wiley-Blackwell, January, 2008, ISBN 1-4051-6260-0

- Stone, Douglas; Patton, Bruce and Heen, Sheila. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most, Penguin, 1999, ISBN 0-14-028852-X

- Ury, William. Getting Past No: Negotiating Your Way from Confrontation to Cooperation, revised second edition, Bantam, January 1, 1993, trade paperback, ISBN 0-553-37131-2; 1st edition under the title, Getting Past No: Negotiating with Difficult People, Bantam, September, 1991, hardcover, 161 pages, ISBN 0-553-07274-9

- Ury, William; Fisher, Roger and Patton, Bruce. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving in, Revised 2nd edition, Penguin USA, 1991, trade paperback, ISBN 0-14-015735-2; Houghton Mifflin, April, 1992, hardcover, 200 pages, ISBN 0-395-63124-6. The first edition, unrevised, Houghton Mifflin, 1981, hardcover, ISBN 0-395-31757-6

- West, R., Turner, L.H. (2007). Introducing Communication Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Johnson, Chandra. "Face time vs. screen time: The technological impact on communication." national.deseretnews.com. Deseret Digital Media. 29 Aug. 2014. Web. 29 Mar. 2016.

- Robinson, Lawrence, Jeanne Segal, and Melinda Smith. "Effective Communication: Improving Communication Skills in Your Work and Personal Relationships." Help Guide. Mar. 2016. Web. 5 April 2016.

- Tardanico, Susan. "Is Social Media Sabotaging Real Communication?" Forbes: Leadership, 30 April 2012. Web. 10 Mar. 2016.

- White, Martha C. "The Real Reason New College Grads Can't Get Hired." time.com. EBSCOhost. 11 Nov. 2013. Web. 12 April 2016.

- Wimer, Jeremy. Manager of Admission Services, Bachelor of Arts in Organizational and Strategic Communication, Master of Science in Management of Organizational Leadership & Change, Colorado Technical University. Personal Email interview. 22 Mar. 2016.

Further reading

- Isa N. Engleberg; Dianna R. Wynn; Maria Roberts (17 February 2014). THINK Interpersonal Communication, First Canadian Edition. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-205-99284-3.