Intestacy

Intestacy is the condition of the estate of a person who dies without having in force a valid will or other binding declaration.[1] Alternatively this may also apply where a will or declaration has been made, but only applies to part of the estate; the remaining estate forms the "intestate estate". Intestacy law, also referred to as the law of descent and distribution, refers to the body of law (statutory and case law) that determines who is entitled to the property from the estate under the rules of inheritance.

| Wills, trusts and estates |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Wills |

|

Sections Property disposition |

| Trusts |

|

Common types Other types

Governing doctrines |

| Estate administration |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

History and the common law

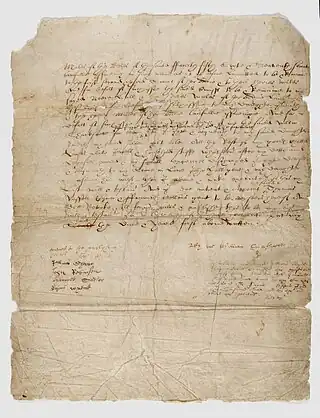

Intestacy has a limited application in those jurisdictions that follow civil law or Roman law because the concept of a will is itself less important; the doctrine of forced heirship automatically gives a deceased person's next-of-kin title to a large part (forced estate) of the estate's property by operation of law, beyond the power of the deceased person to defeat or exceed by testamentary gift. A forced share (or legitime) can often only be decreased on account of some very specific misconduct by the forced heir. In matters of cross-border inheritance, the "laws of succession" is the commonplace term covering testate and intestate estates in common law jurisdictions together with forced heirship rules typically applying in civil law and Sharia law jurisdictions. After the Statute of Wills 1540, Englishmen (and unmarried or widowed women) could dispose of their lands and real property by a will. Their personal property could formerly be disposed of by a testament, hence the hallowed legal merism last will and testament.[2]

Common law sharply distinguished between real property and chattels. Real property for which no disposition had been made by will passed by the law of kinship and descent; chattel property for which no disposition had been made by testament was escheat to the Crown, or given to the Church for charitable purposes. This law became obsolete as England moved from being a feudal to a mercantile society, and chattels more valuable than land were being accumulated by townspeople.

Rules

Where a person dies without leaving a will, the rules of succession of the person's place of habitual residence or of their domicile often apply, but it is also common for the jurisdiction where the property is located to govern its disposal, regardless of the decedent's residence or domicile.[3] In certain jurisdictions such as France, Switzerland, the U.S. state of Louisiana, and much of the Islamic world, entitlements arise whether or not there was a will. These are known as forced heirship rights and are not typically found in common law jurisdictions, where the rules of succession without a will (intestate succession) play a back-up role where an individual has not (or has not fully) exercised their right to dispose of property in a will.

Current law

In most contemporary common-law jurisdictions, the law of intestacy is patterned after the common law of descent. Property goes first or in major part to a spouse, then to children and their descendants; if there are no descendants, the line of inheritance goes back up the family tree to the parents, the siblings, the siblings' descendants, the grandparents, the parents' siblings, and the parents' siblings' descendants, and usually so on further to the more remote degrees of kinship. The operation of these laws varies from one jurisdiction to another.

England and Wales

The rules of succession are the Intestacy Rules set out in the Administration of Estates Act 1925 and associated legislation.

For deaths after 1 October 2014, the rules where someone dies intestate leaving a spouse or civil partner are as follows:

- if there are no issue (i.e. children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren etc.) then the spouse or civil partner inherits the entire estate; or

- if there are issue, the spouse or civil partner receives the personal chattels and the first £270,000, then half of everything else passing under the intestacy rules. The other half passes to the issue on the statutory trusts (see below).

Where there is no spouse or civil partner, the assets pass in the following order of priority, such that no-one is entitled in any lower category if there is a living person entitled in a higher one:

- issue, on the statutory trusts (see below);

- parents;

- full-blood brothers and sisters, on the statutory trusts;

- half-blood brothers and sisters, on the statutory trusts;

- grandparents;

- full-blood uncles and aunts, on the statutory trusts; or

- half-blood uncles and aunts, on the statutory trusts.

In the above "the statutory trusts" mean:

- that a person who would be entitled if they were adult does not become entitled until they attain 18; and

- where a person who would have been entitled has predeceased the intestate, but has left issue, those issue who survive the intestate share, "per stirpes", their ancestor's share.

Where no beneficiaries on the above list exist, the person's estate generally escheats (i.e. is legally assigned) to the Crown (via the Bona vacantia division of the Treasury Solicitor) or to the Duchy of Cornwall or Duchy of Lancaster when the deceased was a resident of either. In limited cases a discretionary distribution might be made by one of these bodies to persons who would otherwise be without entitlement under strict application of the rules of inheritance.[4]

These rules have been supplemented by the discretionary power of the court contained in the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 so that fair provision can be made for a dependent spouse or other relative where the strict divisions set down in the intestacy rules would produce an unfair result, for example by providing additional support for a dependent minor or disabled child vis-a-vis an adult child who has a career and no longer depends on their parent.

Scotland

The law on intestacy in Scotland broadly follows that of England and Wales with some variations. A notable difference is that all possible (blood) relatives can qualify for benefit (i.e. they are not limited to grandparents or their descendants). Once a class is 'exhausted', succession continues to the next line of ascendants, followed by siblings, and so on. In a complete absence of relatives of the whole or half-blood, the estate passes to the Crown (as ultimus haeres). The Crown has a discretion to benefit people unrelated to the intestate, e.g. those with moral claims on the estate.[5]

Canada

In Canada the laws vary from province to province. As in England, most jurisdictions apply rules of intestate succession to determine next of kin who become legal heirs to the estate. Also, as in England, if no identifiable heirs are discovered, the property may escheat to the government.

United States

In the United States intestacy laws vary from state to state.[6] Each of the separate states uses its own intestacy laws to determine the ownership of residents' intestate property. Attempts in the United States to make probate and intestate succession uniform from state to state, through efforts such as the Uniform Probate Code, have been met with limited success.

The distribution of the property of an intestate decedent is the responsibility of the administrator (or personal representative) of the estate: typically the administrator is chosen by the court having jurisdiction over the decedent's property, and is frequently (but not always) a person nominated by a majority of the decedent's heirs.

Federal law controls intestacy of Native Americans.[7]

Many states have adopted all or part of the Uniform Probate Code, but often with local variations,[8] In Ohio, the law of intestate succession has been modified significantly from the common law, and has been essentially codified.[9] The state of Washington also has codified its intestacy law.[10] New York has perhaps the most complicated law of descent of distribution.[11][12] Maryland's intestacy laws specify not only the distribution, but also the order of the distribution among family members.[13] Florida's intestacy statute permits the heirs of a deceased spouse of the decedent to inherit, if the decedent has no other heirs.

See also

References

- "Intestacy". Wex. Cornell Law School. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "NEI Project: Wills and Testaments". familyrecords.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- "Intestate Succession – Where does everything go without a Will?". Pauper Planning Techniques. Curnalia Law, LLC. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- "Guide to Discretionary Grants in Estates Cases". The Treasury Solicitor, Bona Vacantia Division. The National Archives. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Gorham, John (8 July 1999). "A Comparison of the English and Scottish Rules of Intestacy". The Association of Corporate Trustees. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "The Probate Process". American Bar Association. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "25 U.S. Code § 2206 - Descent and distribution". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "UPC Chart (Excerpted from "Record of Passage of Uniform and Model Acts, as of September 30, 2010)" (PDF). Uniform Law Commission. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Title XXI, Courts - Probate - Juvenile, Chapter 2015, Descent and Distribution". Ohio Revised Code. State of Ohio. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "RCW 11.04.015". Revised Code of Washington. Washington State Legislature. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "New York Code, Estates, Powers & Trusts, Sec. 4-1.1. Descent and distribution of a decedent's estate". The New York Senate. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Eager, Samuel Watkins (1926). Descent and distribution : intestate succession in the state of New York. Albany, NY: Matthew Bender & Co. OCLC 5514327.

- "Maryland Intestacy Law". People's Law. Maryland State Law Library. Retrieved 1 March 2019.