Iran–Russia relations

Relations between the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Persian Empire (Iran) officially commenced in 1521, with the Safavids in power.[1] Past and present contact between Russia and Iran have long been complicatedly multi-faceted; often wavering between collaboration and rivalry. The two nations have a long history of geographic, economic, and socio-political interaction. Mutual relations have often been turbulent, and dormant at other times.

| |

Iran |

Russia |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Iran, Moscow | Embassy of Russia, Tehran |

| Envoy | |

| Iranian Ambassador to Russia Kazem Jalali | Russian Ambassador to Iran Alexey Dedov |

_01.jpg.webp)

Until 1720, on the surface, relations between Iran and Russia were largely friendly and the two operated on a level of equity.[2] After 1720, with Peter the Great's attack on Iran and the establishment of the Russian Empire, the first of a long series of campaigns was initiated against Iran and the Caucasus.[2] The Russian Empire had an oppressive role in Iran during the 19th and early 20th centuries which harmed Iran's development, and during most of the ensuing Soviet period, the shadow of the "big northern neighbour" continued to impend.[3] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the two neighboring nations have generally enjoyed very close cordial relations. Iran and Russia are strategic allies[4][5][6] and form an axis in the Caucasus alongside Armenia. Iran and Russia are also military allies in the conflicts in Syria and Iraq and partners in Afghanistan and post-Soviet Central Asia. The Russian Federation is also the chief supplier of arms and weaponry to Iran. Due to Western economic sanctions on Iran, Russia has become a key trading partner, especially in regard to the former's excess oil reserves. Currently Russia and Iran share a close economic and military alliance, and both countries are subject to heavy sanctions by most Western nations.[7][8]

Militarily, Iran is the only country in Western Asia that has been invited (in 2007) to join the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Russia-based international treaty organization that parallels NATO.[9] As soon as he became president, Vladimir Putin pursued close friendship with Iran and deepened Russian military cooperation with Iran and Syria. In 2015, Putin ordered a military intervention in Syria, supporting the Assad regime and its Iranian allies with an aerial bombing campaign against the Syrian opposition. While much of the Iranian military uses Iranian-manufactured weapons and domestic hardware, Iran still purchases some weapons systems from Russia. In turn, Iran assisted Russia with its drone technology and other military technology during its invasion of Ukraine.[10][11]

Iran has its embassy in Moscow and consulates in the cities of Astrakhan and Kazan. Russia has its embassy in Tehran, and consulates in Rasht and Isfahan.

History

Russian Empire

Pre-Safavid era

Contacts between Russians and Persians have a long history, extending back more than a millennium.[12] There were known commercial exchanges as early as the 8th century AD between Persia and Russia.[1] They were interrupted by the Mongol invasions in the 13th and 14th centuries but started up again in the 15th century with the rise of the state of Muscovy. In the 9th–11th century AD, there were repetitive raiding parties undertaken by the Rus' between 864 and 1041 on the Caspian Sea shores of what are nowadays Iran, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan as part of the Caspian expeditions of the Rus'.[13] Initially, the Rus' appeared in Serkland in the 9th century traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves. The first small-scale raids took place in the late 9th and early 10th century. The Rus' undertook the first large-scale expedition in 913; having arrived on 500 ships, they pillaged the Gorgan region, in the territory of present-day Iran, and the areas of Gilan and Mazandaran, taking slaves and goods.

Safavid Empire–Russian Tsardom/Empire

It was not until the 16th century that formal diplomatic contacts were established between Persia and Russia, with the latter acting as an intermediary in the trade between England and Persia. Transporting goods across Russian territory meant that the English could avoid the zones under Ottoman and Portuguese control.[1] The Muscovy Company (also known as the Russian Company) was founded in 1553 to expand the trade routes across the Caspian sea.[1] Moscow's role as an intermediary in exchanges between Britain and Persia led Russian traders to set up business in urban centres across Persia, as far south as Kashan.[1] The Russian victories over the Kazan Khanate in 1552 and the Astrakhan Khanate in 1556 by Tsar Ivan IV (r. 1533–84) revived trade between Iran and Russia via the Volga-Caspian route and marked the first Russian penetration of the Caucasus and the Caspian area.[12] Though these commercial exchanges in the latter half of the 16th century were limited in scope, they nonetheless indicate that the fledgling entente between the two countries emerged as a result of opposition to the neighboring Ottoman Empire.

Diplomatic relations between Russia and Iran date back to 1521, when the Safavid Shah Ismail I sent an emissary to visit the Czar Vasili III. As the first diplomatic contacts between the two countries was being established, Shah Ismail was also working hard with the aim of joining forces against their mutual enemy, neighboring Ottoman Turkey.[1] On several occasions, Iran offered Russia a deal exchanging a part of its territory (for example Derbent and Baku in 1586) for its support in its wars against their Ottoman archrivals.[1] In 1552–53, Safavid Iran and the Muscovy state in Russia exchanged ambassadors for the first time, and, starting in 1586, they established a regular diplomatic relationship. In 1650, extensive contact between the two people, culminated in the Russo-Persian War (1651–53), after which Russia had to cede its footholds in the North Caucasus to the Safavids. In the 1660s the famous Russian Cossack ataman Stenka Razin raided, and occasionally wintered at, Persia's north coast, creating diplomatic problems for the Russian Czar in his dealings with the Persian Shah.[14] The Russian song telling the tragic semi-legendary story of Razin's relationship with a Persian princess remains popular to this day.

Peace reigned for many decades between the two peoples after these conflicts, in which trade and migration of peoples flourished. The decline of the Safavid and Ottoman state saw the rise of Imperial Russia on the other hand. After the fall of Shah Sultan Husayn brought the Safavid dynasty to an end in 1722, the greatest threats facing Persia were Russian and Ottoman ambitions for territorial expansion in the Caspian region—north-western Persia specifically. During the Safavid period, Russian and Persian power was relatively evenly balanced.[1] Overall, the common anti-Ottoman struggle served as the main common political interest for Iran and Russia throughout the period of Safavid rule, with several attempts to conclude an anti-Ottoman military treaty.[12] Following Shah Husayn's fall, the relationship lost its symmetry, but it was largely restored under Nader Shah.[1]

In his later years of rule, Peter the Great found himself in a strong enough position to increase Russian influence more southwards in the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, challenging both the Safavids and the Ottomans. He made the city of Astrakhan his base for his hostilities against Persia, created a shipyard, and attacked the weakened Safavids in the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of its territories in the Caucasus and northern mainland Iran for several years. After several years of political chaos in Persia following the fall of the Safavids, a new and powerful Persian empire was born under the highly successful military leader Nader Shah. Fearing a costly war which would most likely be lost against Nader and also being flanked by the Turks in the west, the Russians were forced to give back all territories and retreat from the entire Caucasus and northern mainland Iran as according to the Treaty of Resht (1732) and Treaty of Ganja (1735) during the reign of Anna of Russia. The terms of the treaty also included the first instance of close Russo-Iranian collaboration against a common enemy, in this case the Ottoman Turks.[15][16] Relations sooned soured, however, after Nader Shah accused the Russians of conspiring against him. The invasion of Dagestan in 1741 was partially directed against Russia; thus the Terek River was left on a high state of alert until Nader Shah's death.[17][18]

Karim Khan Zand promised the Russians certain territories in the northern frontier if they helped him against enemies like the Ottomans.[19]

Qajar Persia–Russian Empire

Irano-Russian relations particularly picked up again following the death of Nader Shah and the dissolution of his Afsharid dynasty which gave eventually way to the Qajarid dynasty in the mid-18th century. The first Qajar Persian Ambassador to Russia was Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi. After the rule of Agha Mohammad Khan, who stabilized the nation and re-established Iranian suzerainty in the Caucasus,[20] the Qajarid government was quickly absorbed with managing domestic turmoil, while rival colonial powers rapidly sought a stable foothold in the region. While the Portuguese, British, and Dutch competed for the south and southeast of Persia in the Persian Gulf, the Russian Empire largely was left unchallenged in the north as it plunged southward to establish dominance in Persia's northern territories. Plagued with internal politics, the Qajarid government found itself incapable of rising to the challenge of facing its northern threat from Russia.

A weakened and bankrupted royal court, under Fath Ali Shah, was forced to sign the notoriously unfavourable Treaty of Gulistan (1813) following the outcome of the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813), irrevocably ceding what is modern-day Dagestan, Georgia, and large parts of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) was the outcome of the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), which resulted in the loss of modern-day Armenia and the remainder of the Azerbaijan Republic, and granted Russia several highly beneficial capitulatory rights, after efforts and initial success by Abbas Mirza failed to ultimately secure Persia's northern front.[21] By these two treaties, Iran lost swaths of its integral territories that had made part of the concept of Iran for centuries.[22] The area to the north of the Aras River, which included the territories of the contemporary nations of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and the North Caucasian Republic of Dagestan, were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[23][24][25][26][27][28] Russia more or less openly pursued a policy to free their newly conquered land from Iran's influence. By doing this, the Russian government helped to create and spread a new Turkic identity that, in contrast to the previous one, was founded on secular principles, particularly the shared language. As a result, many Iranian-speaking residents of the future Azerbaijan Republic at the time either started hiding their Iranian ancestry or underwent progressive assimilation. The Tats and Kurds underwent these integration processes particularly quickly.[29]

Anti-Russian sentiment was so high in Persia during that time that uprisings in numerous cities were formed. The famous Russian intellectual, ambassador to Persia, and Alexander Pushkin's best friend, Alexander Griboyedov, was killed along with hundreds of Cossacks by angry mobs in Tehran during these uprisings. With the Russian Empire still advancing south in the course of two wars against Persia, and the treaties of Turkmanchay and Golestan in the western frontiers, plus the unexpected death of Abbas Mirza in 1823, and the murder of Persia's Grand Vizier (Abol-Qasem Qa'em-Maqam), Persia lost its traditional foothold in Central Asia.[30] The Treaty of Akhal, in which the Qajarid's were forced to drop all claims on Central Asia and parts of Turkmenistan, topped off Persian losses to the global emerging power of Imperial Russia.

.jpg.webp)

In the same period, by a proposal of the Shah with the backing of the Tsar, the Russians founded the Persian Cossack Brigade, which and would prove to be crucial in the next few decades of Iranian history and Irano-Russian relations. The Persian Cossacks were organized along Russian lines and controlled by Russian officers.[31] They dominated Tehran and most northern centers of living. The Russians also organized a banking institution in Iran, which they established in 1890.[32]

During the 19th century, Russians dealt with Iran as an inferior "Orient", and held its people in contempt whilst ridiculing all aspects of Iranian culture.[33] The Russian version of contemporaneous Western attitudes of superiority differed however. As Russian national identity was divided between East and West and Russian culture held many Asian elements, Russians consequently felt equivocal and even inferior to Western Europeans. In order to stem the tide of this particular inferiority complex, they tried to overcompensate to Western European powers by overemphasizing their own Europeanness and Christian faith, and by expressing scornfully their low opinion of Iranians. The historian Elena Andreeva adds that this trend was not only very apparent in over 200 Russian travelogues written about Iran and published in the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, but also in diplomatic and other official documents.[33]

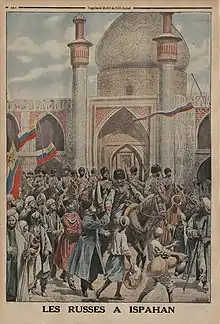

In 1907, Russia and Britain divided Iran into three segments that served their mutual interests, in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907.[31] The Russians gained control over the northern areas of Iran, which included the cities of Tabriz, Tehran, Mashad, and Isfahan. The British were given the southeastern region and control of the Persian Gulf, and the territory between the two regions was classified as neutral territory.

Russia's influence in northern Iran was paramount from the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[33] During this time period, it stationed troops in Iran's Gilan, Azerbaijan and Khorasan provinces, and its diplomatic offices (consulates) in these parts wieleded considerable power. These consulates dominated the local Iranian administration and in some circumstances even collected local taxes. Starting in the same year as the Anglo-Russian Convention, unpremeditated Russian colonization commenced in Mazandaran and Astarabad provinces. Then, in 1912, Russian foreign policy officially adopted the plan to colonize northern Iran. At the outbreak of World War I, there were most likely some 4,000 Russian settlers in Astarabad and Mazandaran, whereas in northeastern Iran the Russians had founded a minimum of 15 Russian villages.[33]

During the reign of Nicholas II of Russia, Russian occupational troops played a major role in the attempted Tsarist suppression of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.[3][33] In the dawn of the outbreak of World War I, Russian occupational forces occupied Qajar Iran's Azerbaijan province as well as the entire north and north-east of the country, and amounted to circa twenty thousand.[34] Following the start of the Persian Campaign of World War I, the number of Russian troops in Iran moderately grew to some eighty or ninety thousand.

As a result of the major Anglo-Russian influence in Iran, at a high point, the central government in Tehran was left with no power to even select its own ministers without the approval of the Anglo-Russian consulates. Morgan Shuster, for example, had to resign under British and Russian diplomatic pressure on the Persian government. Shuster's book The Strangling of Persia: Story of the European Diplomacy and Oriental Intrigue That Resulted in the Denationalization of Twelve Million Mohammedans is an account of this period, criticizing the policies of Russian and Britain in Iran.[35]

These, and a series of climaxing events such as the Russian shelling of Mashad's Goharshad Mosque in 1911, and the shelling of the Persian National Assembly by the Russian Colonel V. Liakhov, led to a surge in widespread anti-Russian sentiments across the nation.

Pahlavi–Soviet Union

One result of the public outcry against the ubiquitous presence of Imperial Russia in Persia was the Constitutionalist movement of Gilan, which followed up the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. Many participants of the revolution were Iranians educated in the Caucasus, direct émigrés (also called Caucasian muhajirs) from the Caucasus, as well as Armenians that at the same period were busy with establishing the Dashnaktsutyun party as well as operations directed against the neighboring Ottoman Empire. The rebellion in Gilan, headed by Mirza Kuchak Khan led to an eventual confrontation between the Iranian rebels and the Russian army, but was disrupted with the October Revolution in 1917.

As a result of the October Revolution, thousands of Russians fled the country, many to Persia. Many of these refugees settled in northern Persia creating their own communities of which many of their descendants still populate the country. Some notable descendants of these Russian refugees in Persia include the political activist and writer Marina Nemat and the former general and deputy chief of the Imperial Iranian Air Force Nader Jahanbani, whose mother was a White émigré.

Russian involvement however continued on with the establishment of the short-lived Persian Socialist Soviet Republic in 1920, supported by Azeri and Caucasian Bolshevik leaders. After the fall of this republic, in late 1921, political and economic relations were renewed. In the 1920s, trade between the Soviet Union and Persia reached again important levels. Baku played a particularly significant role as the venue for a trade fair between the USSR and the Middle East, notably Persia.[36]

In 1921, Britain and the new Bolshevik government entered into an agreement that reversed the division of Iran made in 1907. The Bolsheviks returned all the territory back to Iran, and Iran once more had secured navigation rights on the Caspian Sea. This agreement to evacuate from Iran was made in the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship (1921), but the regaining of Iranian territory did not protect the Qajar dynasty from a sudden coup d'état led by Colonel Reza Shah.[31]

In the 1920s-1930s, the Soviet secret service (Cheka-OGPU-NKVD) carried out clandestine operations on Iranian soil as it tried to eliminate White émigrées that had moved to Iran.[37] In 1941, as the Second World War raged, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom launched an undeclared joint invasion of Iran, ignoring its plea of neutrality.

In a revealing cable sent on July 6, 1945, by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the local Soviet commander in northern Azerbaijan was instructed as such:

- "Begin preparatory work to form a national autonomous Azerbaijan district with broad powers within the Iranian state and simultaneously develop separatist movements in the provinces of Gilan, Mazandaran, Gorgan, and Khorasan".[38]

After the end of the war, the Soviets supported two newly formed in Iran, the Azerbaijan People's Government and the Republic of Mahabad, but both collapsed in the Iran crisis of 1946. This postwar confrontation brought the United States fully into Iran's political arena and, with Cold War starting, the US quickly moved to convert Iran into an anti-communist ally.

Soviet Union–Islamic Republic (post 1979)

The Soviet Union was the first state to recognize the Islamic Republic of Iran, in February 1979.[39] During the Iran–Iraq War, however, it supplied Saddam Hussein with large amounts of conventional arms. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini deemed Islam principally incompatible with the communist ideals (such as atheism) of the Soviet Union, leaving the secular Saddam as an ally of Moscow. However, during the war, the USA imposed an arms embargo on Iran, and the Soviet Union supplied arms to Iran via North Korea.

After the war, in 1989, Iran made an arms deal with Soviet Union.[40] With the fall of the USSR, Tehran–Moscow relations experienced a sudden increase in diplomatic and commercial relations, and Russia soon inherited the Soviet-Iranian arms deals. By the mid-1990s, Russia had already agreed to continue work on developing Iran's nuclear program, with plans to finish constructing the nuclear reactor plant at Bushehr, which had been delayed for nearly 20 years.

During the East Prigorodny conflict, and Georgian–Ossetian conflict, Iran secretly supported Ossetian separatism against Georgia, and sided with the Ossetians against Ingush and Chechens in the conflict.

Putin–Khamenei years

As tension between the United States and Iran escalates, the country is finding itself further pushed into an alliance with Russia, as well as China. Iran, like Russia, "views Turkey's regional ambitions and the possible spread of some form of pan-Turkic ideology with suspicion".[41]

Military

Prior to the Iranian revolution Iran's air fleet was entirely Western-made but in the 21st century Iran's Air Force and civilian air fleet are increasingly becoming domestically and Russian-built as the US and Europe continue to maintain sanctions on Iran.[42][43][44]

In May 2007 Iran was invited to join the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Russia-based international treaty organization that parallels NATO.[9][45] The invitation came from the desk of then CSTO Secretary-General Nikolai Bordyuzha, who said that "the CSTO is an open organization. If Iran applies in accordance with our charter, we will consider the application." It was stated by a Western observer that the accession failed "basically due to the ayatollahs’ opposition to join a military bloc clearly dominated by a traditionally rival power of Iran such as Russia."[45] Another Western observer points out that, like NATO, CSTO has a mutual defense treaty clause whereby attack against one is considered an attack against all and was concerned about the difficulty posed by a possible conflagration of the Iran-Israel variety.[9] In November 2014 Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki head Sergey Naryshkin floated the idea of admitting Iran as an observer to the CSTO Parliamentary Assembly.[9][46]

In 2010, Iran's refusal to halt uranium enrichment led the UN to pass a new resolution, number 1929 to vote for new sanctions against Iran which bans the sale of all types of heavy weaponry (including missiles) to Iran. This resulted in the cancellation of the delivery of the S-300 system to Iran:[47] In September 2010 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree banning the delivery of S-300 missile systems, armored vehicles, warplanes, helicopters and ships to Iran. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad criticised Russia for kowtowing to the United States.[48] As a result of the cancellation, Iran brought suit against Russia in Swiss court and in response to the lawsuit Russia threatened to withdraw diplomatic support for Iran in the nuclear dispute.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Iran and Russia have become the Syrian government's principal allies in the conflict, openly providing armed support. Meanwhile, Russia's own relations with the West plummeted due to the Russo-Ukrainian War, the 2018 Skripal poisoning incident in Great Britain, and alleged Russian interference with Western politics, prompting the U.S. and Europe to retaliate with sanctions against Russia. As a result, Russia has shown a degree willingness to ally with Iran militarily. Following the JCPOA agreement, President Vladimir Putin lifted the S-300 ban in 2015 and the deal for the missile defense system to Iran was revived.[49] The delivery was completed in November 2016 and was to be followed by a $10 billion deal that included helicopters, planes and artillery systems.[50]

In January 2021 Iran, China and Russia held their third joint naval exercise, the third joint exercise of the three countries, in the northern Indian Ocean and the Sea of Oman area. The joint exercise of the three countries began in 2019 in the Indian Ocean.[51]

Ukraine war

According to the United States, Russia sought to acquire drones from Iran during the Russo-Ukrainian War, with a Russian delegation visiting Kashan Airfield south of Tehran in June and July 2022 to observe drones manufactured by Iran.[52] Iran criticized the assessment by the United States, saying that it would not supply Russia or Ukraine with military equipment during the war, instead demanding that both nations seek a peaceful resolution.[53] In September 2022, the Ukrainian military claimed that it encountered an Iranian-supplied suicide drone used by Russia, publishing images of the wreckage of the drone.[54] On October 6, 2022, Iran agreed to provide "additional" surface to air missiles and drones to Russia.[55] On October 24, 2022, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian said Iran would "not remain indifferent" if it is "proven that Iranian drones are being used in the Ukraine war against people," but claimed defense cooperation between Iran and Russia would continue.[56]

According to various media outlets, as of 2023, the American intelligence has claimed that Iran has been assisting Moscow in building a drone factory within its borders to maintain its war machine in Ukraine.[57][58]

In August 2023, The White House has reportedly urged Iran to cease selling armed drones to Russia as part of broader discussions in Qatar and Oman, aimed at de-escalating the nuclear crisis. This effort runs alongside negotiations for a prisoner exchange deal, which recently led to the transfer of Iranian-US citizens from prison to house arrest. The US seeks to prevent Iran from supplying drones and spare parts to Russia, currently used in the Ukrainian conflict.[59]

Trade

Russia and Iran also share a common interest in limiting the political influence of the United States in Central Asia. This common interest has led the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) to extend to Iran as observer status in 2005, and offer full membership in 2006. The Iranians attained full membership status on 17 September 2021.[60] Moscow and Beijing supported Tehran's successful bid for full membership in the SCO.[61]

Iran and Russia have co-founded the Gas Exporting Countries Forum along with Qatar.

In addition to their trade and cooperation in hydrocarbons, Iran and Russia have also expanded trade ties in many non-energy sectors of the economy, including a large agriculture agreement in January 2009 and a telecommunications contract in December 2008.[62] In July 2010, Iran and Russia signed an agreement to increase their cooperation in developing their energy sectors. Features of the agreement include the establishment of a joint oil exchange, which with a combined production of up to 15 million barrels of oil per day has the potential to become a leading market globally.[63] Gazprom and Lukoil have become increasingly involved in the development of Iranian oil and gas projects.

In 2005, Russia was the seventh largest trading partner of Iran, with 5.33% of all exports to Iran originating from Russia.[64] Trade relations between the two increased from US$1 billion in 2005 to $3.7 billion in 2008.[62] Motor vehicles, fruits, vegetables, glass, textiles, plastics, chemicals, hand-woven carpet, stone and plaster products were among the main Iranian non-oil goods exported to Russia.[65]

In 2014, relations between Russia and Iran increased as both countries are under U.S. sanctions and were seeking new trade partners. The two countries signed a historic US$20 billion oil for goods deal in August 2014.[66][67][68]

In 2021, trade between the nations rose 81% to a record $3.3 billion.[69]

President Ebrahim Raisi, who was elected in 2021, seemed to prioritize trade with Russia.[61] In early 2022, Ebrahim Raisi traveled to Russia at the invitation of his Russian counterpart. He handed over Iran's proposed draft for a 20-year cooperation agreement between Iran and Russia during his trip.[61]

With the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 by Russia, the U.S. and other nations have imposed sanctions on Russia.[70] In the opinion of at least one Western writer, in order to evade sanctions, Iran and Russia could be working together to create a "clandestine banking and finance system to handle tens of billions of dollars in annual trade banned under U.S. led sanctions."[71]

On 20 March 2022 it was reported that Iran, in the person of Agriculture Minister Javad Sadatinejad, had signed a deal in Moscow with Russia to import 20 million tons of basic goods including vegetable oil, wheat, barley and corn.[72]

In May 2022 Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak and Iranian Oil Minister Javad Owji, joint co-chairs of the Russian-Iranian Intergovernmental Commission had a meeting in Tehran at which they discussed such items as oil swaps, increasing joint investments, a possible free trade zone, adding to the Russian-built Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant, and developing the long-delayed North-South Transport Corridor, a rail cargo route from all the way from Russia to India, among other items.[69]

Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Tehran on 19 July 2022 to meet with his Iranian counterpart Ebrahim Raisi and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The Turkish president was previously involved to mediate in the 2022 Ukraine conflict. The three nations have been holding talks in recent years as part of the "Astana peace process" to end more than 11 years of civil war in Syria. Iran and the Russian Federation attempt to boost economic ties after being hit by Western sanctions.[73]

In December 2022, Russia and Iran announced a new transcontinental trade route from the eastern edge of Europe to the Indian Ocean. The passage spans 3,000-kilometers and could be established beyond the reach of Western sanctions. Russia and Iran share similar economic pressures amid sanctions – and both look east to integrate their growing economies.[74]

In early February 2023, Tehran and Moscow announced they fully linked the Russian Financial Messaging System of the Bank of Russia (SPFS) with Iran's SEPAM national financial messaging service; both countries had been excluded from SWIFT. Bilateral economic ties had intensified since sanctions were placed on Russia after the 2022 Russian invasion of the Ukraine, and chances for the revival of the JCPOA with Iran faded in late 2022. In 2022/23, Russia with US$2.7 billion is by far the largest investor in the sanctioned Iranian economy. As both countries face dramatically devalued currencies, Russia and Iran aim to link their payment system to larger economies such as India and China.[75]

In May 2023, the US said that Iran and Russia are working to build more drones which will be used against Ukraine.[57]

In June 2023, Iran's Transport Minister, Mehrdad Bazrpash, announced plans to create a joint shipping company with the Russian Federation. Iran places great emphasis on the importance of the Volga and Caspian Seas for trade with Russia. Both countries have reached a quadrilateral agreement with Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan regarding the transit of oil products and grain.[76]

Eurasian Economic Union

As Iran and Russia economic and geo-political relations have improved over the years, Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) have opted for Iran to join the EEU as well. Currently, only one EEU country, Armenia, shares a land border with Iran, but the Caspian Sea provides a direct link between Iran and Russia.

Iran has expressed interest in joining the EEU. A meeting between Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was held in 2015 to discuss the prospect of cooperation between the customs union and Iran. According to the Iranian Ambassador to Russia, Mehdi Sanaei, Iran is focusing on signing an agreement with the EEU in 2015 regarding mutual trade and reduction of import tariffs to central Asian countries and trading in national currencies as part of the agreement rather than in US dollars.[77]

In May 2015, the Union gave the initial go-ahead to signing a free trade agreement with Iran. Andrey Slepnev, the Russian representative on the Eurasian Economic Commission board, described Iran as the EEU's "key partner in the Middle East" in an expert-level EEU meeting in Yerevan. Viktor Khristenko furthermore noted that Iran is an important partner for all the EEU member states. He stated that "Cooperation between the EEU and Iran is an important area of our work in strengthening the economic stability of the region".[78]

Sanctions

Both Russia and Iran are subject to Western sanctions, and each extended period of sanctions seems to improve the relationship between them. This, however, has changed somewhat following the imposition of sanctions against both Russia and Iran. Improving the countries’ respective ties with the US proved more difficult than forging closer ties between Moscow and Tehran. Since March 2014, In response to Russia's annexation of Crimea and the purposeful destabilization of Ukraine, the EU, the US, and a number of other Western nations have gradually adopted restrictive sanctions against Russia. In retaliation, Russia imposed its own restrictions on Western nations, prohibiting the import of some food items. In November 2018, the JCPOA-lifted Iran sanctions were entirely reinstated by the Trump administration.[81]

Polls

According to 2015 data from Pew Research Center, 54% of Russians have a negative opinion of Iran, with 34% expressing a positive opinion.[82] According to a 2013 BBC World Service poll, 86% of Russians view Iran's influence positively, with 10% expressing a negative view.[83] A Gallup poll from the end of 2013 showed Iran ranked as sixth greatest threat to peace in the world according to Russian view (3%), after United States (54%), China (6%), Iraq (5%), and Syria (5%).[84] According to a December 2018 survey by IranPoll, 63.8% of Iranians have a favorable view of Russia, with 34.5% expressing an unfavorable view.[85]

See also

References

- Relations between Tehran and Moscow, 1979–2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Matthee, Rudi (2013). "Rudeness and Revilement: Russian–Iranian Relations in the Mid-Seventeenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 333. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.758500. S2CID 145596080.

- Volkov, Denis V. (2022). "Bringing democracy into Iran: a Russian project for the separation of Azerbaijan". Middle Eastern Studies. 58 (6): 1. doi:10.1080/00263206.2022.2029423. S2CID 246923610.

- Ozbay, Fatih; Aras, Bulent (2008). "The limits of the Russian-Iranian strategic alliance: its history and geopolitics, and the nuclear issue". Korean Journal of Defense Analysis. 20 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/10163270802006321. hdl:11729/299. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "The Strategic Partnership of Russia and Iran". Strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Russia and Iran: Strategic Partners or Competing Regional Hegemons? A Critical Analysis of Russian-Iranian Relations in the Post-Soviet Space". Studentpulse.com. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- MacFarquhar, Neil (13 April 2015). "Putin Lifts Ban on Russian Missile Sales to Iran". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Borshchevskaya, Anna (2022). Putin's War in Syria. 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK: I. B. Tauris. pp. 53–58. ISBN 978-0-7556-3463-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Lin, Christina (February 2015). "Iran UN Sanctions Relief – The Road Towards S-400 and Deterring US/Israeli Airstrikes?" (PDF). 321. ISPSW Strategy Series.

- "White House: Iran preparing to supply Russia with drones". Reuters. Reuters. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- Borshchevskaya, Anna (2022). Putin's War in Syria. 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK: I. B. Tauris. pp. 2, 53, 55, 132, 149, 156. ISBN 978-0-7556-3463-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "RUSSIA i. Russo-Iranian Relations up to the Bolshevik Revolution". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Logan (1992), p. 201

- O'Rourke, Shane (2000). Warriors and Peasants. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). "Treaty of Ganja (1735)". In Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed.). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 329. ISBN 978-1598843361.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tucker, Ernest (2006). "Nāder Shah". Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Axworthy, Michael (24 March 2010). The sword of Persia : Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-85773-347-4. OCLC 1129683122.

- Volkov, Sergey. Concise History of Imperial Russia.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Gershevitch, Ilya; Yarshater, Ehsan; Hambly, G. R. G.; Melville, C.; Boyle, John Andrew; Frye, Richard Nelson; Jackson, Peter (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- Kazemzadeh 1991, pp. 328–330.

- Cronin, Stephanie (2012). The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society under Riza Shah, 1921–1941. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1136026942.

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- E. Ebel, Robert, Menon, Rajan (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- Çiçek, Kemal, Kuran, Ercüment (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernest Meyer, Karl, Blair Brysac, Shareen (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ter-Abrahamian 2005, p. 121.

- Nasser Takmil Homayoun. Kharazm: What do I know about Iran?. 2004. ISBN 964-379-023-1 p.78.

- Ziring, Lawrence (1981). Iran, Turkey, and Afghanistan, A Political Chronology. United States: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-03-058651-8.

- Basseer, Clawson & Floor 1988, pp. 698–709.

- Andreeva, Elena (2014). "RUSSIA i. Russo-Iranian Relations up to the Bolshevik Revolution". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Volkov, Denis V. (2022). "Bringing democracy into Iran: a Russian project for the separation of Azerbaijan". Middle Eastern Studies. 58 (6): 4. doi:10.1080/00263206.2022.2029423. S2CID 246923610.

- Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia: Story of the European Diplomacy and Oriental Intrigue That Resulted in the Denationalization of Twelve Million Mohammedans. ISBN 0-934211-06-X

- Forestier-Peyrat, Etienne (2013). "Red Passage to Iran: The Baku Trade Fair and the Unmaking of the Azerbaijani Borderland, 1922–1930". Ab Imperio. 2013 (4): 79–112. doi:10.1353/imp.2013.0094. ISSN 2164-9731. S2CID 140676760.

- Volkov, Denis V. (2022). "Bringing democracy into Iran: a Russian project for the separation of Azerbaijan". Middle Eastern Studies. 58 (6): 7. doi:10.1080/00263206.2022.2029423. S2CID 246923610.

- Decree of the CC CPSU Politburo to Mir Bagirov, CC Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, on "measures to Organize a Separatist Movement in Southern Azerbaijan and Other Provinces of Northern Iran". Translation provided by The Cold War International History Project at The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- Goodarzi, Jubin M. (January 2013). "Syria and Iran: Alliance Cooperation in a Changing Regional Environment" (PDF). Middle East Studies. 4 (2): 31–59. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "Russian Arms and Technology Transfers to Iran:Policy Challenges for the United States | Arms Control Association". armscontrol.org. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Herzig Edmund, Iran and the former Soviet South, Royal Institute for International Affairs, 1995, ISBN 1-899658-04-1, p.9

- "Middle East | Iran air safety hit by sanctions". BBC News. 6 December 2005. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "Iran to buy five TU 100-204 planes from Russia". Payvand.com. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- Johnson, Reuben (November 2005). "Iran is captive market for Tu-204". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- Valvo, Giovanni (14 December 2012). "Syria, Iran And The Future Of The CSTO – Analysis". Eurasia Review.

- "Iran, other states might become observers at CSTO parliamentary assembly — Naryshkin". TASS. 6 November 2014.

- John Pike. "Analysts Say Iran-Russia Relations Worsening". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Al-ManarTV:: Ahmadinejad Slams Russia for US "Sell out" over S-300 03/11/2010". Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- "Russia Ban On S-300s To Iran Lifted". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "Russia Completes S-300 Delivery to Iran | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "India Iran, China and Russia hold naval drills in north Indian Ocean". Reuters. 21 January 2022.

- Bertrand, Natasha (15 July 2022). "Exclusive: Russians have visited Iran at least twice in last month to examine weapons-capable drones". CNN. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- Frantzman, Seth J. (16 July 2022). "Iran tries to downplay potential drone transfers to Russia - analysis". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- Gambrell, Jon (14 September 2022). "Ukraine's military claims downing Iran drone used by Russia". AP News. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Iran agrees to ship missiles, more drones to Russia". Reuters. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Iran will not remain indifferent if proven Russia using its drones in Ukraine - official". Reuters. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- "US says Iran is helping Russia build drone manufacturing facility". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- Shoaib, Alia. "Iran's attack drones have become a key weapon in Russia's war arsenal. Now Tehran is helping Putin to build his own factory to produce them, says the White House". Business Insider. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- Smith, Gordon (16 August 2023). "FirstFT: US presses Iran to stop selling drones to Russia". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "CSTO, SCO summits presage policy of wary tolerance of Taliban regime in Afghanistan". Eurasianet. 17 September 2021.

- "What next for Iran and Russia ties after Raisi-Putin meeting?". Al Jazeera. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Tehran Times". 3 February 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Iran Investment Monthly Aug 2010.pdf" (PDF). Turquoisepartners.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "The Cost of Economic Sanctions on Major Exporters to Iran". Payvand.com. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "Economy". Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Trotman, Andrew (6 August 2014). "Vladimir Putin signs historic $20bn oil deal with Iran to bypass Western sanctions". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "Russia and Iran strike oil agreement". CNBC.com. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Jonathan Saul and Parisa Hafezi (2 April 2014). "Iran, Russia working to seal $20 billion oil-for-goods deal: sources". Reuters. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Russia, Iran Tighten Trade Ties Amid US Sanctions". Bloomberg News. 25 May 2022.

- "What are the sanctions on Russia and are they hurting its economy?". BBC News. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- Zweig, Mark Dubowitz and Matthew (5 April 2022). "Opinion | Iran's Master Class in Evading Sanctions". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Iran Signs Deal With Russia To Import 20 Million Tons Of Basic Goods". Volant Media UK Limited. 20 March 2022.

- "Putin and Erdogan will visit Iran for summit on Syria". lemonde. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- "Russia and Iran Are Building a Trade Route That Defies Sanctions". bloomberg.

- "What’s behind Iran and Russia’s efforts to link banking systems?" aljazeera. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- "Iran and Russia want to unite the fleet". UKRAINIAN SHIPPING MAGAZINE. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- "Iran Seeks Trade Agreement with Eurasian Union". Asbarez.com. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "Tehran Times". 14 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Iran at odds with allied Russia after Moscow backs UAE in island dispute". CNBC. 12 July 2023.

- "حرکت جنجالی اکانت وزارت خارجه روسیه به زبان عربی درباره خلیج فارس+عکس". روزنامه دنیای اقتصاد. 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- "The Russia-Iran Relationship in a Sanctions Era". www.ui.se. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- "Global Indicators Database". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- 2013 World Service Poll Archived 2015-10-10 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- "End of year 2013 : Russia" (PDF). Wingia.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- "State of Iran Survey Series". IranPoll. 8 February 2019.

Sources and further reading

- Atkin, Muriel. Russia and Iran 1780 - 1828 (U of Minnesota Press, 1980)

- Basseer, P.; Clawson, P.; Floor, W. (1988). "Banking". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 7. pp. 698–709.

- Blake, Kristen. The U.S.-Soviet confrontation in Iran, 1945-1962: a case in the annals of the Cold War (University Press of America, 2009).

- Cronin, Stephanie. Iranian-Russian Encounters: Empires and Revolutions Since 1800. Routledge, 2013. ISBN 978-0415624336.

- Deutschmann, Moritz (2013). ""All Rulers are Brothers": Russian Relations with the Iranian Monarchy in the Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 383–413. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.759334. S2CID 143785614.

- Deutschmann, Moritz. Iran and Russian Imperialism: The Ideal Anarchists, 1800-1914. Routledge, 2015. ISBN 978-1138937017.

- Esfandiary, Dina, and Ariane Tabatabai, eds. Triple Axis: Iran's Relations with Russia and China (I. B. Tauris, 2018). 256 pages.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.

- Geranmayeh, Ellie. "The Newest Power Couple: Iran and Russia Band Together to Support Assad" World Policy Journal (2016) 33#4 pp 84–88.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Peter, Avery; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz, Russia and Britain in Persia, A study in Imperialism, (1968) online

- Nejad, Kayhan A. (2021). "To break the feudal bonds: the Soviets, Reza Khan, and the Iranian left, 1921-25". Middle Eastern Studies. 57 (5): 758–776. doi:10.1080/00263206.2021.1897578. S2CID 233524659.

- Raine, Fernande. "Stalin and the creation of the Azerbaijan democratic party in Iran, 1945." Cold war history 2.1 (2001): 1-38.

- Sefat Gol, Mansour, and Seyed Mehdi Hosseini Taghiabad. "From Attempts to Form a Coalition to Worsened Relations; Transformation in Iran and Russia Relations in the Seventeenth Century." Central Eurasia Studies 13.1 (2020): 91–116. online

- Shlapentokh, Dmitry. "Russian elite image of Iran: From the late Soviet era to the present" (Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2009) online.

- Sicker, Martin. The Bear and the Lion: Soviet Imperialism and Iran (Praeger, 1988).

- Ter-Abrahamian, Hrant (2005). "On the Formation of the National Identity of the Talishis in Azerbaijan Republic". Iran and the Caucasus. Brill. 9 (1): 121–144. doi:10.1163/1573384054068132.

- Valizadeh, Akbar, and Mohammad Reza Salehi. "Effective Components within Iran-Russia Security Cooperation in Central Asia." Central Eurasia Studies 13.1 (2020): 299-323 online.

- Volkov, Denis V. Russia’s Turn to Persia: Orientalism in Diplomacy and Intelligence (Cambridge UP, 2018)

- Whigham, Henry James. The Persian problem: an examination of the rival positions of Russia and Great Britain in Persia with some account of the Persian Gulf and the Bagdad Railway (1903) online.

- Zubok, Vladislav M. "Stalin, Soviet Intelligence, and the Struggle for Iran, 1945–53." Diplomatic History 44#1 (2020) pp. 22–46

2022 Ukraine War

- "Ukraine war: what new missiles is Iran providing to Russia and what difference will they make?". Daniel Salisbury. The Conversation. 3 November 2022.

- "Iran may be preparing to arm Russia with short-range ballistic missiles". Josh Lederman and Courtney Kube. NBC News. November 2022.

- "Iran has a direct route to send Russia weapons – and Western powers can do little to stop the shipments". Lauren Kent and Salma Abdelaziz. CNN. 26 May 2023.

- "US assesses Russia now in possession of Iranian drones, sources say". Natasha Bertrand. CNN. 30 August 2022.

- "Kyiv calls for 'liquidation' of Iranian plants building weapons for Russia". Times of Israel.

- "Iran Might Be Waiting Until October To Supply Russia Deadlier Drones And Missiles For Ukraine". Paul Iddon. Forbes.

- "Iranian Weapons Are Now Being Used on Both Sides of the Ukraine War". Adam Rawnsley, Asawin Suebsaeng. Rolling Stone. 17 March 2023.

- "Iranian Weapons Are Now Being Used on Both Sides of the Ukraine War". Adam Rawnsley, Asawin Suebsaeng. Rolling Stone. 17 March 2023.

External links

Media related to Relations of Iran and Russia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Relations of Iran and Russia at Wikimedia Commons- Embassy of Iran in Russia Official website

- Embassy of Russia in Iran Official website

- RUSSIA i. Russo-Iranian Relations up to the Bolshevik Revolution.

- RUSSIA iii. Russo-Iranian Relations in the Post-Soviet Era (1991–present)

- Gorbachev and Iran from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- World Press Review: Bear Hugs, Iran-Russian relations

- Russian-Iranian Relations: Functional Dysfunction Archived 2010-02-01 at the Wayback Machine