Petroleum industry in Iraq

Iraq was the world's 5th largest oil producer in 2009, and has the world's fifth largest proven petroleum reserves. Just a fraction of Iraq's known fields are in development, and Iraq may be one of the few places left where vast reserves, proven and unknown, have barely been exploited. Iraq's energy sector is heavily based upon oil, with approximately 94 percent of its energy needs met with petroleum. In addition, crude oil export revenues accounted for over two-thirds of GDP in 2009. Iraq's oil sector has suffered over the past several decades from sanctions and wars, and its oil infrastructure is in need of modernization and investment. As of June 30, 2010, the United States had allocated US$2.05 billion to the Iraqi oil and gas sector to begin this modernization, but ended its direct involvement as of the first quarter of 2008. According to reports by various U.S. government agencies, multilateral institutions and other international organizations, long-term Iraq reconstruction costs could reach $100 billion (US) or higher.[2]

History

During the 20th century the Ottoman Empire granted a concession allowing William Knox D'Arcy to explore oil fields in its territories which, after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, became the modern countries of Turkey and Iraq. Eventually D'Arcy and other European partners founded the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) in 1912, which was renamed the Iraqi Petroleum Company in later years.[4][5][6]

After the partition of the Ottoman Empire, the British gained control of Mosul in 1921.[4] In 1925, TPC obtained a 75-year concession to explore for oil in exchange for a promise that the Iraqi government would receive a royalty for every ton of oil extracted. A well was located at Baba Gurgur just north of Kirkuk. Drilling started, and in the early hours of 14 October 1927 oil was struck. The oil field in Kirkuk proved extensive.[7]

Discovery of oil in Kirkuk hastened the negotiations over the composition of TPC, and on 31 July 1928 shareholders signed a formal partnership agreement to include the Near East Development Corporation (NEDC)—an American consortium of five large US oil companies that included Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil Company of New York (Socony), Gulf Oil, the Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Company, and Atlantic Richfield Co. (By 1935, only Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York were left).[8][9] The agreement was called the Red Line Agreement for the "red line" drawn around the former boundaries of the Ottoman Empire.[10][11] The Red Line Agreement lasted until 1948 when two of the American partners broke free. During the period, IPC monopolized oil exploration inside the Red Line; excluding Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, where ARAMCO (formed in 1944 by renaming of the Saudi subsidiary of Standard Oil of California (Socal)) and Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO) respectively held controlling position.[10]

After Muhammad Mossadegh nationalized the oil industry in Iran, IPC agreed to accept an "equal profit sharing" arrangement in 1952. Instead of a flat royalty payment, Iraq would be paid 12.5% of the sale price of each barrel.[12] However, foreign company control of Iraq's oil assets was unpopular and in 1958 Abd al-Karim Qasim overthrew Faisal II of Iraq. After seizing control of the Iraqi government, Qasim demanded better terms from IPC but decided against nationalization of Iraq's petroleum assets.[4]

In 1961 Iraq passed Public Law 80 whereby Iraq expropriated 95% of IPC's concessions and the Iraq National Oil Company was created and empowered to develop the assets seized from IPC under Law 80. This arrangement continued in 1970 when the government demanded even more control over IPC, eventually nationalizing IPC after negotiations between the company and the government broke down. By this time the Ba'ath Party was in power in Iraq and Saddam Hussein was its de facto ruler, although Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr did not formally step down as President until 1979.[13][14]

In February 2007, during the Iraq War, the Iraqi cabinet approved a draft law that would distribute oil revenues to the various regions and provinces of Iraq based on population, and would also give regional oil companies the authority to enter into contractual arrangements directly with foreign companies concerning the exploration and development of oil fields. Iraqis remained divided over provisions allowing regional governments to enter into contracts directly with foreign companies; while strongly supported by Kurds, Sunni Arabs wanted the Oil Ministry to retain signing power. As a compromise the draft law proposed that a new body called the Federal Oil and Gas Council would be created that could, in some circumstances, prevent execution of contracts signed by regional governments.[15]

Oil

Reserves

---2017---US-EIA---Jo-Di-graphics.jpg.webp)

- See: Oil reserves in Iraq

According to the Oil and Gas Journal, Iraq's proven oil reserves are 115 billion barrels, although these statistics have not been revised since 2001 and are largely based on 2-D seismic data from nearly three decades ago. Geologists and consultants have estimated that relatively unexplored territory in the western and southern deserts may contain an estimated additional 45 to 100 billion barrels (bbls) of recoverable oil. Iraqi Oil Minister Hussain al-Shahristani said that Iraq is re-evaluating its estimate of proven oil reserves, and expects to revise them upwards. A major challenge to Iraq's development of the oil sector is that resources are not evenly divided across sectarian-demographic lines. Most known hydrocarbon resources are concentrated in the Shiite areas of the south and the ethnically Kurdish north, with few resources in control of the Sunni minority. The majority of the known oil and gas reserves in Iraq form a belt that runs along the eastern edge of the country. Iraq has 9 fields that are considered super giants (over 5 billion bbls) as well as 22 known giant fields (over 1 billion bbls). According to independent consultants, the cluster of super-giant fields of southeastern Iraq forms the largest known concentration of such fields in the world and accounts for 70 to 80 percent of the country's proven oil reserves. An estimated 20 percent of oil reserves are in the north of Iraq, near Kirkuk, Mosul and Khanaqin. Control over rights to reserves is a source of controversy between the ethnic Kurds and other groups in the area.[16]

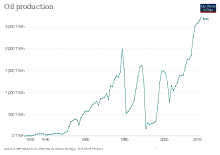

Production

In 2009, Iraq's crude oil production averaged 2.4 million barrels per day (mbd), about the same as 2008 levels, and below its pre-war production capacity level of 2.8 million mbd After the end of the US invasion the production increased on a high level, even though a new invasion from the so-called ISIL started. Production in March 2016 stood at 4.55 million barrels a day. Which is a new all-time peak year for Iraq if OPEC talks about freezing or reduce production held in April 2016 will not led to a reduction. The old peak was 1979 with 171.6 million tons of oil compared to 136.9 million tons produced in 2011 and 152.4 million tons in 2012.[17] The company's geographical operation area spans the following governorates: Kirkuk, Nineveh, Erbil, Baghdad, Diyala, and part of Babil to Hilla and Wasit to Kut. The remainder falls under the jurisdiction of the SOC and MOC, and though smaller in geographical size, includes the majority of proven reserves. MOC's oil fields hold an estimated 30 billion barrels of reserves. They include Amarah, Field, Huwaiza, Noor, Rifaee, Dijaila, Kumait and East Rafidain.[18]

A 2012 report by the International Energy Agency estimated that Iraq could increase production from 2.95 mbd in 2012 to 6.1 mbd by 2020, which would increase Iraq's oil revenues to $5 trillion between 2012 and 2035, or around $200 billion per year.[4]

Development plans

Iraq has begun an ambitious development program to develop its oil fields and to increase its oil production. Passage of the proposed Hydrocarbons Law, which would provide a legal framework for investment in the hydrocarbon sector, remains a main policy objective. Despite the absence of the Hydrocarbons Law, the Ministry of Oil (Iraq) signed 12 long-term contracts between November 2008 and May 2010 with international oil companies to develop 14 oil fields. Under the first phase, companies bid to further develop 6 giant oil fields that were already producing with proven oil reserves of over 43 billion barrels. Phase two contracts were signed to develop oil fields that were already explored but not fully developed or producing commercially. Together, these contracts cover oil fields with proven reserves of over 60 billion barrels, or more than half of Iraq's current proven oil reserves. As a result of these contract awards, Iraq expects to boost production by 200,000 bbl/d by the end of 2010, and to increase production capacity by an additional 400,000 bbl/d by the end of 2011. When these fields are fully developed, they will increase total Iraqi production capacity to almost 12 million bbl/d, or 9.6 million bbl/d above current production levels. The contracts call for Iraq to reach this production target by 2017.

Infrastructure constraints

Iraq faces many challenges in meeting this timetable. One of the most significant is the lack of an outlet for significant increases in crude oil production. Both Iraqi refining and export infrastructure are currently bottlenecks and need to be upgraded to process much more crude oil. Iraqi oil exports are currently running at near full capacity in the south, while export capacity in the north has been restricted by sabotage, and would need to be expanded in any case to export significantly higher volumes. Production increases of the scale planned will also require substantial increases in natural gas and/or water injection to maintain oil reservoir pressure and boost oil production.

Iraq has associated gas that could be used, but it is currently being flared. Another option is to use water for re-injection, and locally available water is currently being used in the south of Iraq. However, fresh water is an important commodity in the Middle East, and large amounts of seawater will likely have to be pumped in via pipelines that have yet to be built. ExxonMobil has coordinated initial studies at water injection plans for many of the fields under development. According to their estimate, 10–15 million bbl/d of seawater could be necessary for Iraq's expansion plans, at a cost of over $10 billion.

Furthermore, Iraq's oil and gas industry is the largest industrial customer of electricity, with over 10 percent of total demand. Large-scale increases in oil production would also require large increases in power generation. However, Iraq has struggled to keep up with the demand for power, with shortages common across Iraq. Significant upgrades to the electricity sector would be needed to supply additional power. Iraq also plans to sign delineation agreements on shared oil fields with Kuwait and Iran. Iraq would like to set up joint committees with its neighbors on how to share the oil.

According to the Oil and Gas Journal, Iraq's proven natural gas reserves are 112 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), the tenth largest in the world. An estimated 70 percent of these lie in Basra governorate in the south of Iraq. Probable Iraqi reserves have been estimated at 275–300 Tcf, and work is currently underway by several IOCs and independents to accurately update hydrocarbon reserve numbers. Two-thirds of Iraq's natural gas resources are associated with oil fields including, Kirkuk, as well as the southern Nahr Bin) Umar, Majnoon, Halfaya, Nassiriya, the Rumaila fields, West Al-Qurnah, and Zubair. Just under 20 percent of known gas reserves are non-associated; around 10 percent is salt dome gas. The majority of non-associated reserves are concentrated in several fields in the North including: Ajil, Bai Hassan, Jambur, Chemchemal, Kor Mor, Khashem al-Ahmar, and Khashem al-Ahmar.

Service contracts licensing results

| Field / block | Company | Home country | Company type | Share in field | Plateau production target (bpd) | Service fee per bbl ($) | Gross revenue at plateau ($/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majnoon | Shell | Netherlands | Public | 45% | 1,800,000 | 1.39 | 410,953,500 |

| Majnoon | Petronas | Malaysia | State | 30% | 1,800,000 | 1.39 | 273,969,000 |

| Halfaya | CNPC | China | State | 37.5% | 535,000 | 1.4 | 102,519,375 |

| Halfaya | Petronas | Malaysia | State | 18.75% | 535,000 | 1.4 | 51,259,688 |

| Halfaya | Total | France | Public | 18.75% | 535,000 | 1.4 | 51,259,688 |

| Rumaila | BP | UK | Public | 37.5% | 2,850,000 | 2 | 780,187,500 |

| Rumaila | CNPC | China | State | 37.5% | 2,850,000 | 2 | 780,187,500 |

| Zubair | KPRRM | UK | Public | 18.81% | 1,200,000 | 2 | 183,415,300 |

| Zubair | ENI | Italy | Public | 37.81% | 1,200,000 | 2 | 287,415,600 |

| Zubair | Occidental | US | Public | 23.44% | 1,200,000 | 2 | 205,334,400 |

| Zubair | KOGAS | Korea | State | 18.75% | 1,200,000 | 2 | 164,250,000 |

| West Qurna Field Phase 2 | Lukoil | Russia | Public | 75% | 1,800,000 | 1.15 | 566,662,500 |

| Badra | Gazprom | Russia | State | 30% | 170,000 | 5.5 | 102,382,500 |

| Badra | Petronas | Malaysia | State | 15% | 170,000 | 5.5 | 51,191,250 |

| Badra | KOGAS | Korea | State | 22.5% | 170,000 | 5.5 | 76,786,875 |

| Badra | TPAO | Turkey | State | 7.5% | 170,000 | 5.5 | 25,595,625 |

| West Qurna Field Phase 1 | Exxon | US | Public | 60% | 2,325,000 | 1.9 | 967,432,500 |

| West Qurna Field Phase 1 | Shell | Netherlands | Public | 15% | 2,325,000 | 1.9 | 241,858,125 |

| Qayara | Sonangol | Angola | State | 75% | 120,000 | 5 | 164,250,000 |

| Najmah | Sonangol | Angola | State | 75% | 110,000 | 6 | 180,675,000 |

| Garraf | Petronas | Malaysia | State | 40% | 230,000 | 1.49 | 56,288,475 |

| Garraf | JAPEX | Japan | Public | 30% | 230,000 | 1.49 | 37,525,650 |

| Missan Group | CNOOC | China | State | 63.75% | 450,000 | 2.30 | 240,831,562.5 |

| Missan Group | TPAO | Turkey | State | 11.25% | 450,000 | 2.30 | 42,499,687.5 |

Notes: 1. Field shares are as a % of the total. The Iraq state retains a 25% share in all fields for which Service Contracts have been awarded.

Export pipelines

To the North: Iraq has one major crude oil export pipeline, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Oil Pipeline, which transports oil from the north of Iraq to the Turkish port of Ceyhan. This pipeline has been subject to repeated disruptions this decade, limiting exports from the northern fields. Iraq signed an agreement with Turkey to extend the operation of the 1.6 million bbl/d pipeline, as well as to upgrade its capacity by 1 million bbl/d. In order for this pipeline to reach its design capacity, Iraq would need to receive oil from the south via the Strategic Pipeline, which was designed to allow flows of crude oil from the south of Iraq to go north via Turkey, and vice versa. Iraq has proposed building a new strategic line from Basra to the northern city of Kirkuk, with the line consisting of two additional crude oil pipelines. To the West: The Kirkuk–Baniyas pipeline (opened 1952) has been closed and the Iraqi portion reported unusable since the 2003 war in Iraq. Discussions were held between Iraqi and Syrian government officials to re-open the pipeline. It had a design capacity of 300,000 bbl/d, on top of the capacity of the existing 12 and 16-inch pipes of the Kirkuk–Haifa oil pipeline, which it looped. The Russian company Stroytransgaz accepted an offer to fix the pipeline in December 2007, but no follow-up was made. Iraq and Syria have discussed building several new pipelines, including a 1.5 million bbl/d pipeline carrying heavy crude oil, and a 1.25 million bbl/d pipeline for carrying light crudes. To the South: The 1.65 million bbl/d Iraq Pipeline to Saudi Arabia (IPSA) has been closed since 1991 following the Persian Gulf War. There are no plans to reopen this line. Iraq has also held discussions to build a crude oil pipeline from Haditha to Jordan's port of Aqaba.

Ports

.png.webp)

The Basra Oil Terminal on the Persian Gulf has an effective capacity to load 1.3 million bbl/d and support Very Large Crude Carriers. In February 2009, the South Oil Company commissioned Foster Wheeler to carry out the basic engineering design to rehabilitate and expand capacity of the terminal by building four single point mooring systems with a capacity of 800,000 bbl/d each. According to former Minister of Oil Issam al-Chalabi, it would take at least until 2013 to complete the project if financing is found. There are five smaller ports on the Persian Gulf, all functioning at less than full capacity, including the Khor al-Amaya terminal.

Overland export routes

Overland routes are used to export limited amounts of crude from small fields bordering Syria. In addition, Iraq has resumed shipping oil to Jordan's Zarqa refinery by road tankers at a rate of 10,000 bbl/d.

Downstream

Estimates of Iraqi nameplate refining capacity vary, from 637,500 bbl/d according to the Oil and Gas Journal to 790,000 bbl/d according to the Special Inspector General for Iraqi Reconstruction. Iraqi refineries have antiquated infrastructure and only half run at utilization rates of 50 percent or more. Despite improvements in recent years, the sector has not been able to meet domestic demand of about 600,000 bbl/d, and the refineries produce too much heavy fuel oil and not enough other refined products. As a result, Iraq relies on imports for 30 percent of its gasoline and 17 percent of its LPG. To alleviate product shortages, Iraq's 10-year strategic plan for 2008-2017 set a goal of increasing refining capacity to 1.5 million bbl/d, and is seeking $20 billion in investments to achieve this target. Iraq has plans for 4 new refineries, as well as plans for expanding the existing Daura and Basra refineries.

Natural gas

Gas production

Iraqi natural gas production rose from to 81 (billion) Bcf in 2003 to 522 Bcf in 2008. Some is used as fuel for power generation, and some is re-injected to enhance oil recovery. Over 40 percent of the production in 2008 was flared due to a lack of sufficient infrastructure to utilize it for consumption and export, although Royal Dutch Shell estimated that flaring losses were even greater at 1 Bcf per day. As a result, Iraq's five natural gas processing plants, which can process over 773 billion cubic feet per year, sit mostly idle. To reduce flaring, Iraq has been working on an agreement with Royal Dutch Shell to implement a 25-year project to capture flared gas and provide it for domestic use. Iraq's cabinet gave preliminary approval for the $17 billion deal covering development of 25–30 Tcf of associated natural gas reserves in Basra province through a new joint venture, Basra Gas Company. The agreement, which originally was to cover all of Basra Governorate, has been modified to include only the associated gas from the Rumaila, Zubair, and West Qurna Phase I projects. Implementation of this agreement is necessary for the new oil development projects to go forward.

Upstream development

Iraq has planned an upstream bidding round in late 2010 for three non-associated natural gas fields with combined reserves of over 7.5 Tcf. This will be the third hydrocarbon bidding round conducted by Iraq, following two earlier rounds that were held to develop Iraq's oil fields. All of the companies that prequalified to bid in the two earlier rounds will be invited. Iraq has committed to purchasing 100 percent of the gas.

Midstream

Plans to export natural gas remain controversial due to the amount of idle and sub-optimally fired electricity generation capacity in Iraq—much a result of a lack of adequate gas feedstock. Prior to the 1990–1991 Gulf War, Iraq exported natural gas to Kuwait. The gas came from Rumaila through a 105 miles (169 km) pipeline with a capacity of 400 million cubic feet (11 million cubic metres) per day to Kuwait's central processing center at Kuwait. In 2007, the Ministry of Oil announced an agreement to fund a feasibility study on the revival of the mothballed pipeline. Iraq has eyed northern export routes such as the proposed Nabucco pipeline through Turkey to Europe, and in July 2009 Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki suggested that Iraq could be exporting 530 Bcf per year to Europe by 2015. A second option is the Arab Gas Pipeline (AGP) project. The proposed AGP pipeline would deliver gas from Iraq's Akkas field to Syria and then on to Lebanon and the Turkish border sometime in 2010, and then on to Europe. Other proposals have included building LNG exporting facilities in the Basra region.

See also

References

- "Country Analysis Brief: Iraq". US Energy Information Administration. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Donovan, Thomas W. "Iraq's Petroleum Industry: Unsettled Issues". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2006. p. 817. ISBN 1593394926.

- ILEI-Oil-and-Gas-Law.pdf (PDF), retrieved 2018-06-12

- J. Zedalis, Rex (September 2009). The Legal Dimensions of Oil and Gas in Iraq | Current Reality and Future Prospects. Cambridge University Press. p. 360. ISBN 9780521766616.

- "IPC - History and early development". Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Morton, Michael Quentin (May 2006). In the Heart of the Desert (In the Heart of the Desert ed.). Aylesford, Kent, United Kingdom: Green Mountain Press (UK). ISBN 978-0-9552212-0-0. 095522120X. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- "MILESTONES: 1921-1936, The 1928 Red Line Agreemen". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Business & Finance: Socony-Vacuum Corp". Time. 1931-08-10. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- Stephen Hemsley Longrigg (1961). Oil in the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 237163. OL 5830191M.

- Daniel Yergin (1991). The Prize (The prize ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-50248-4. 0671502484. TPC was renamed the Iraqi Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1929.

- Samir Saul (2007). "Masterly Inactivity as Brinkmanship: The Iraq Petroleum Company's Route to Nationalization, 1958-1972". The International History Review. 29 (4): 746–792. doi:10.1080/07075332.2007.9641140. JSTOR 40110926.

- Benjamin Shwadran (1977). Middle East Oil: Issues and Problems. Transaction Publishers. p. 30f. ISBN 0-87073-598-5.

- Toyin Falola; Ann Genova (2005). The Politics of the Global Oil Industry: An Introduction. Praeger/Greenwood. p. 61. ISBN 0-275-98400-1.

- Wong, Edward (2007-02-27). "Iraqi cabinet approves national oil law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- "Industry in Iraq". Middleeast Arab. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "statistical review of world energy 2013" (PDF). British Petroleum. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Sorkhabi, Rasoul. "Iraq". Oil Edge. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)