Bolton, Dickens & Co.

Bolton, Dickens & Co. was a slave-trading business of the antebellum United States, headquartered in Memphis, Tennessee. Several of principals of the firm eventually shot and killed one another as part of a long-running dispute over money. A Bolton & Dickens account ledger survived the American Civil War and is a valuable primary source on the interstate slave trade.

Family business

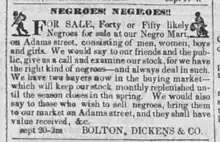

Beginning in 1846, a clan by the name of Bolton began using the Mississippi River and rail lines for slave arbitrage, which is to say buying and selling people as commodities.[1] Beginning in 1850, Wade H. Bolton, Isaac L. Bolton, Jefferson L. Bolton, Washington Bolton, and Thomas Dickins formed a business partnership, which continued until 1857.[2][3] According to Chase C. Mooney's history of slavery in Tennessee, "Dickins did much of the scouting around; Washington was at Lexington; Isaac spent most of his time at Vicksburg; and Wade looked after the Memphis office."[4] One John H. Bolton, a lawyer, was also involved indirectly.[3] The Boltons and the Dickins family also intermarried. (Note: The family name seems to have been Dickins but the firm name is typically spelled Dickens.) Bolton, Dickens & Co. make multiple brief appearances in Harriet Beecher Stowe's A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, including a reprint of an advertisement apparently placed by Thomas Dickins: "NEGROES WANTED. I will pay at all times the highest price in cash for all good negroes offered. I am buying for the Memphis and Louisiana markets, and can afford to pay, and will pay, as high as any trading man in this State. All those having negroes to sell will do well to give me a call at No. 210, corner of Sixth and Wash streets, St. Louis, Mo. Thos. Dickins."[5]

Bolton, Dickens & Co. had an "immense slave pen at the foot of Howard Row on the river front" in Memphis.[6] Highly networked and entrepreneurial, the ring expanded rapidly and eventually had Bolton & Dickens branches in a number of American cities, including New Orleans, Vicksburg, Mobile, Lexington, Richmond, Charleston, Natchez, St. Louis, and Jefferson City, Missouri.[7] [8][9] They also built a strong network of contacts through mentorship and patronage; one of their more enterprising trainees was Nathan Bedford Forrest, who later opened a competing retail storefront in close proximity to where the Bolton operation in Memphis.[1] (Recent research into Forrest's slave-trading business has not been able to verify this apprenticeship, which had been reported in Memphis histories since the 1800s.)[10]

As one history put it, "To summarize the general business plan, Bolton, Dickins and Co. sent agents to places where enslaved people were no longer needed, bought them, and forced them to move to markets where they could be sold for more money...Bolton, Dickens & Co. might buy 20 slaves from someone in St. Louis and sell them to someone in New Orleans; or buy 50 in Memphis and sell them in Vicksburg, Miss.; or buy 100 in Vicksburg and deliver them to Texas."[8]

In 1855 Bolton, Dickens & Co. bought the slave jail they had previously belonged to Lewis C. Robards of Lexington, Ky.[11] At their peak, presumably in 1856, the Bolton family reportedly had a net worth of US$1,000,000 (equivalent to $32,570,370 in 2022).[12] Court records include a claim that the firm had annual transactions "amounting in the aggregate to several millions of dollars.[13]

Family feud

In what amounted to a West Tennessee gangland war, at least half a dozen people were shot or killed in relation to Bolton, Dickens & Co. business dispute beginning in around 1856 and ending 1870.[12][3] One account claims 19 people were killed.[6]

Somewhere between 1855 to 1857 (sources conflict), a Kentucky slave trader named James McMillan sold a person to the Bolton & Dickens firm who was legally free ("the unexpired term of a free negro apprentice, and Bolton brought him to Memphis and sold him as a slave for life").[3] Selling a free person as a slave was a felony,[3] lawyers got a judgment against Bolton & Dickens, and there were legal fees; McMillan refused to return the payment he'd received from Bolton & Dickens or compensate them for their costs.[14] Isaac Bolton lured McMillan to Memphis and shot and killed him.[2][15] Bolton was going to be hanged by the mob for his crime, but apparently Nathan Bedford Forrest saved his life. Per a Tennessee lawyer writing memoir-as-Confederate literature in 1895: "General Forrest threw himself headlong in the breach, mounted a box, with pistol drawn, after the rope was around Bolton's neck, and told the mob that the man or men who dared to pull on the rope and take Bolton's life, must and should die with him on the spot. This brought the mob to immediately recognize its own danger, and their intended victim was not further molested. The iron nerve and will of this one man, so greatly distinguished afterwards in the civil war, saved the life of Bolton."[3] According to Frederic Bancroft, this is total hokum, adapting a Forrest-aggrandizing legend associated with another crime and further adapting the fiction to fit the Bolton–Dickins feud narrative.[16]

Bolton was ultimately acquitted of the crime (in part thanks to bribing witnesses and jurors), and then paid his legal expenses out of the business, which was not good for the profits of his partners, and that kicked off the feud, as Tom Dickins felt he was suffering unfairly for Bolton's legal troubles.[12] [17] According to one account the defense of Bolton cost US$300,000 (equivalent to $10,146,923 in 2022).[3] There were plans to resolve matters by shotgun duel but then the American Civil War broke out and such matters were tabled for the duration.[3]

In approximately 1868, a man named Wilson and female servant, Nancy, were shot and killed.[2] Wade H. Bolton and E.C. Patterson (a son-in-law of Isaac Bolton and supposedly a cousin to U.S. Representative Thomas Patterson) were charged with shooting and killing Nancy through the window.[3]

In 1869, two men, Inman and Morgan, "were tracked into a cave in North Alabama and killed."[2]

On July 14, 1869, Tom Dickins shot Wade H. Bolton in downtown Memphis.[15] Bolton later died from his injuries.[2]

On July 30, 1870, Tom Dickins was "waylaid and killed in the Hatchie bottom, a short distant from Memphis."[2] He was killed with two shotgun blasts heard from a distance; his horse returned to the stable covered in blood. Dickins' killer was never identified.[14] Two weeks later Dickins' son Samuel Dickins was bushwhacked and killed at the same place.[18]

Isaac Bolton left a wildly idiosyncratic will (complete with imprecations labeling various relatives traitors and Judases), amongst which named beneficiaries were the widow of Stonewall Jackson ($10,000), $300 each to heads of families of formerly enslaved people that still worked on his farm (and $100 each to those unmarried), and an endowment bequest that ultimately funded the establishment of what is now Bolton High School in Tennessee.[17]

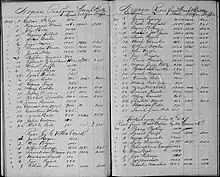

Business ledger

A company ledger dating from 1856 to 1858 is held at the New-York Historical Society.[20][19] The Memphis Public Library has a full digital transcript made by Shirley C. Neeley. Per the catalog notes, "Pages 1-38 are a day-to-day accounting by Isaac Bolton for the months of March and April 1865. Pages 39-79 list the names of slaves, purchase prices, etc. Pages 80-91 include entries for sale of slaves. Pages 92-99 are transcriptions of correspondence and the last section includes newspaper articles and advertisements."[7]

See also

- Negro mart

- Nashville Market House – Slave auction house and commercial building in Tennessee

- African-American genealogy – Field of genealogy pertaining to African-Americans

- List of American slave traders

- History of Memphis, Tennessee

- West Tennessee

- Tennessee in the American Civil War

References

- "Slave Dealers, Trading Companies, and their Product – Setting The Record Straight". Our Memphis History. 2023-02-06. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- "Goodspeed History of Shelby Co. TN". www.tngenweb.org. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- Hallum, John (1895). The diary of an old lawyer: or, Scenes behind the curtain. Nashville, Tenn.: Southwestern publishing house. p. 70.

- Mooney, Chase C. (1971) [1957]. "Chapter Two: Hire, Sale, Theft and Flight of Slaves". Slavery in Tennessee (Reprint ed.). Westport, Conn.: Negro Universities Press. p. 48. OCLC 609222448 – via HathiTrust.

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). "Chapter II: Mr. Haley & Chapter IV: The Slave Trade". A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. p. 356. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.

- Daily public ledger. [volume] (Maysville, Ky.), 23 March 1903. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. page 3 <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069117/1903-03-23/ed-1/seq-3/>

- "Bolton, Dickens & Co. Record of Slaves, 1856-1858". memphislibrary.contentdm.oclc.org. Compiled by Shelly. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Content, Contributed (2023-05-01). "The rise of Memphis as a center for cotton and the slave trade". www.elizabethton.com. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- Turner, Wallace B. (1960). "Kentucky Slavery in the Last Ante Bellum Decade". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 58 (4): 291–307. ISSN 0023-0243. JSTOR 23374678.

- Huebner, Timothy S. (March 2023). "Taking Profits, Making Myths: The Slave Trading Career of Nathan Bedford Forrest". Civil War History. 69 (1): 42–75. doi:10.1353/cwh.2023.0009. ISSN 1533-6271. S2CID 256599213.

- Clark, Thomas D. A history of Kentucky. p. 197–199. Retrieved 2023-08-31 – via HathiTrust.

- Patton, Bill (2020). History Lover's Guide to Memphis & Shelby County, A. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-1-4671-4237-3.

- McDaniel, W. Caleb (2019-08-07). Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-19-084700-5.

- Hale, James L. (2014). The Long Road to Freedom: The Story of the Enslaved Polley Children. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4834-1370-9.

- Kazek, Kelly (2011-01-03). Forgotten Tales of Tennessee. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62584-148-3.

- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931]. Slave Trading in the Old South. Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman. University of South Carolina Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8.

- Tennessee Department of Public Instruction (1905). Annual Report of ... State Superintendent of Public Instruction for Tennessee, for the Scholastic Year Ending ... pp. 368–373.

- Harkins, John E. (2008). Historic Shelby County: An Illustrated History. HPN Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-893619-86-9.

- "Bolton, Dickens & Co. account book, 1856–1858". New York Historical Society Digital Collections. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- "Upper cover". cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

Further reading

- Marcinko, Cathy; Spencer, Lydia, eds. (June 2000). "The Bolton-Dickens Feud". Old Shelby County Magazine. No. 19. Memphis: Pastimes Press. pp. 2–11.